Simplified Wellness – Workshop 6 (Resilience & Work-Life Balance)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Resilience & Work-Life Balance is provided by Mrs Sciortino Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Ms Sciortino is a Certified Learning Provider (CLP) with Appleton Greene. An internationally renowned author, Simplicity Expert and Professional Speaker, she spent almost two decades as a high-functioning, award-winning executive before she experienced a life-changing event that forced her to stop and ask the question: ‘What if there’s a better way to live?’.

Embarking on a journey to answer this question, she uncovered a simple system to challenge the status quo and use the power of questions to purposefully direct life.

A highly accomplished businesswoman, she is an official member of the Forbes Coaches Council, has received nominations for the Top Female Author awards, was awarded a prestigious silver Stevie International Business Women Award, named as the recipient of a 2022 and 2023 CREA Global Award and has also been awarded over 20 international awards for the uniqueness of the tools and resources she offers.

Sought globally for expert comment by media, she’s been featured in podcasts, Facebook Live, YouTube, blog articles, print media and in live TV and Radio.

She works globally with corporate programs, conference platforms, retreats, professional mentoring and in the online environment to teach people how easy it is to live life in a very different way.

When not working, she can be found in nature, on the yoga mat, lost in a great book, meditating, hanging out with her husband and her house panthers or creating magic in her kitchen.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

In some ways, the messaging around the need to be more resilient has forced people into carrying more stress and experiencing more burnout. The more you force yourself to be resilient, the more likely it is that your work/life balance will be out of kilter as well. Sure, an ability to be resilient is a good thing and a great skill to have in your kitbag, but when your whole focus is on constantly building more resilience so that you can stay upright, it’s time to stop and take a look at what you really need to focus on in your life. This module focuses on pulling back the curtains on resilience so you can understand what resilience really is, how much of it you actually need and then shows you how to create the simple things you can do every day to seamlessly blend your work and your life without constantly being under pressure.

Objectives

01. What is Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. History of Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Resilient Businesses: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Resilient People: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Cognitive Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Physical Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Emotional Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Psychological Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Social Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

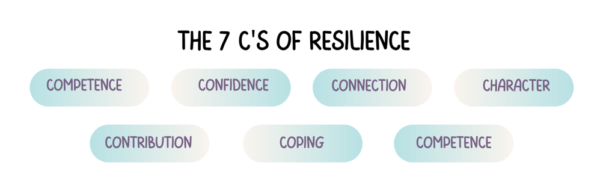

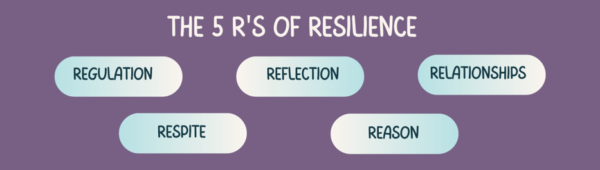

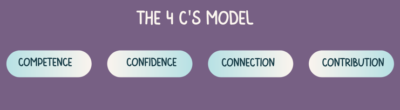

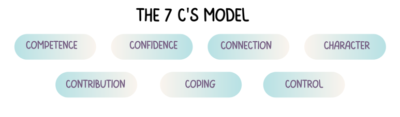

10. Concepts of Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Resilience Scales: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Models of Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. What is Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. History of Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Resilient Businesses: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Resilient People: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Cognitive Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Physical Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Emotional Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Psychological Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Social Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Concepts of Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Resilience Scales: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Models of Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse What is Resilience.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse History of Resilience.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Resilient Businesses.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Resilient People.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Cognitive Resilience.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Physical Resilience.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Emotional Resilience.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Psychological Resilience.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Social Resilience.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Concepts of Resilience.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Resilience Scales.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Models of Resilience.

Introduction

The sixth workshop in the Simplified Wellness Program – Resilience – takes you on a deep dive into the topic of resilience so you can better understand what it truly is and the ways you can develop and use it to improve your experience of life.

Resilience is the process and result of overcoming difficult or demanding life situations, particularly through mental, emotional, and behavioral flexibility and adaptation to internal and external challenges.

How well people adapt to adversity depends on a number of elements, the most important of which are:

• the perspectives and interactions that people have with the world;

• the quantity and caliber of social resources; and

• particular coping mechanisms

Psychological studies have shown that the resources and abilities linked to more positive adaptation – that is, more resilience – aren’t necessarily inherited, but rather can be developed and practiced.

This module takes you on a deep dive into the topic of resilience so you can better understand what it truly is and the ways you can develop and use it to improve your experience of life.

History

Resilience first appeared as a concept in the early 17th Century, where it was developed from the Latin verb ‘resilire’ which itself gained a meaning in the English language of rebound or recoil.

The term resilience doesn’t seem to appear in any documented works until it was introduced into literature written by Thomas Tredgold in 1818, when he used the term to describe the strength of beams of timber.

In 1856, Robert Mallett then further developed the concept of resilience by applying it as a measurement in relation to the ability of particular materials to tolerate particular shocks.

Thus, resilience was first seen as a form of measurement used in engineering and construction-focused endeavors.

In the 20th Century, resilience started to be used as a measurement in new fields. Researchers started to apply resilience measures in relation to child psychology and being exposed to particular threats in the 1970s. In this application, people were assessed for their ability to recover from adversity. Those who showed a higher aptitude for being able to recover were then said to be ‘resilient’. Professor Sir Michael Rutter was one of the many researchers who was interested in a variety of risk encounters and their corresponding results.

In 1973, C.S. Holling then began to apply resilience theory through the lens of ecology, which in turn shaped his work, Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. During this time, ecological resilience became known as a measure of the persistence of systems and of their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between state variables.

Holling discovered that a similar framework may be used to describe various types of resilience. Later, further personal, cultural, and societal applications were drawn in using the ecosystems application.

Within the ecological system, instability to neutral systems might result from the effects of fires, changes in the forest community, or the process of fishing, in addition to the climatic events mentioned by Holling. Contrarily, stability is the capacity of a system to resume its equilibrium condition following a brief perturbation.

Ecological and social resilience, in contrast to material and mechanical resilience, emphasize the redundancy and durability of several equilibrium states to preserve function.

From this research, and the application to other personal, cultural and societal fields, the most common definition of resilience emerged and was accepted as being the successful adaptation in the face of difficulty.

Since this time, resilience research has gone through a number of stages. Psychologists started to realize that a lot of what seems to foster resilience comes from outside of the individual, after initially focusing on the ‘unflappable’ or ‘unbeatable’ child.

The quest for resilience-building elements at the individual, family, community, cultural and, more recently, at the organizational levels, resulted from this realization.

There is growing interest in resilience as a quality shared by entire organizations, communities and cultural groupings, in addition to the influences that community and culture have on resilience in individuals. The idea that resilience is a process has benefited from the discovery by modern researchers that resilience components vary in various risk scenarios.

In order to support relative resistance, researchers are also interested in how certain protective factors interact with risk factors and other protective factors. Two further ideas are resilient reintegration, which holds that overcoming hardship propels people to a higher level of development, and the idea that resilience is an intrinsic talent that just needs to be properly awakened.

Current Position

Building resilience in organizations, and in the individuals within the organizations, is rightly earning its place as an important focal point for organization boards around the world.

Over the last few decades, organizations have started to attempt adoption of resilient practices and embed programs that assist in creating resilience in their people. However, on the whole the resilience industry has provided services at either the low-cost, generic end or at the high-cost, personalized solution end of the market.

As a relatively new concept, resilience as a topic has not been well understood within organizations, and therefore expertise relating to resilience has to be brought into the organization from external providers. With barriers to entry into most industries falling thanks to technological advances, there are more participants competing for the same buyers in a marketplace.

Technology has also provided pathways to producing and supplying products and services at lower cost than ever before. All of that combined has left most organizations with limited expenditure available to focus on health and wellbeing activities, and therefore believing that they are stuck having to access the low cost, generic solutions available in the marketplace.

The key issue with this approach is that a generic solution doesn’t provide answers for the unique needs of each individual within an organization. So, instead of shoring up the resilience of its people, an organization finds itself stuck in a cycle of survival and not being able to move forwards.

Therefore, organizations’ resilience levels tend to remain stagnant, or worsen as stress levels rise and higher levels of resilience are needed to be able to cope with the demands of the situation.

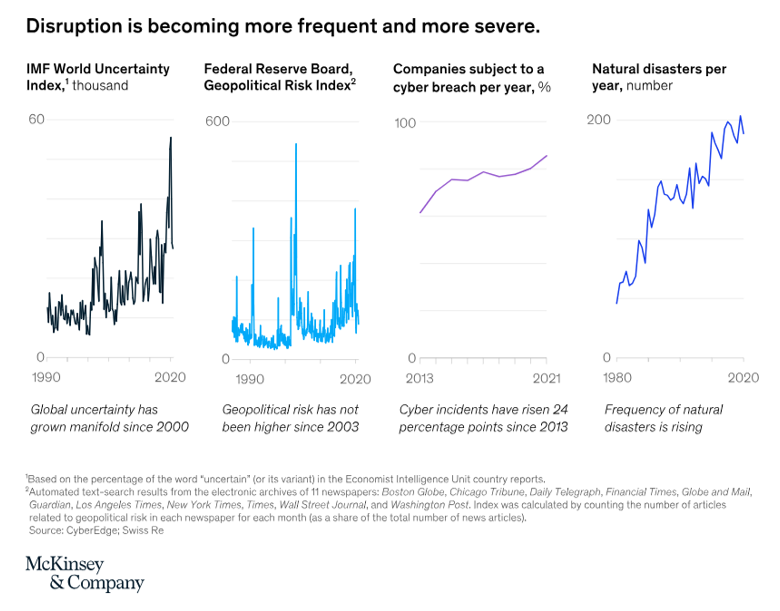

In a world that is continually changing, the viability and sustainability of organizations are still being put to the test. Many firms have come to the realization that conventional corporate strategies do not adequately shield them against unforeseen catastrophes. Organizations must be able to absorb a change-requiring event, adapt, and keep their competitive advantage and profitability.

Future Outlook

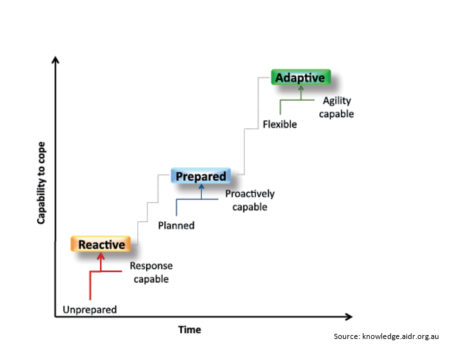

Until recently, organizations tended to approach challenging events and situations in a set way. They would either:

• accept that events are too challenging and will therefore cause the organization to cease operating;

• find themselves in a challenging situation and do what they have to do in order to survive (including existing in a reduced form if that is what is required);

• move to a reduced form initially, and then plan to rebound back to the pre-challenge status as quickly as possible; or

• use the challenge and adversity to create a pathway that enables it to move forward in leaps and bounds.

With multiple threats faced concurrently by organizations globally, the need for resilience within organizations, and in the individuals within those organizations, has never been greater.

The resilience industry will need to morph and expand its focus once again, and focus on the niche requirements within organizations. Topics such as cyber, community, digital mindset and infrastructure and accelerated AI innovation will all need resilience models built around them.

Individuals will need to build resilience levels to deal with the demands that changes in these niches will bring. Furthermore, organizations will need to ensure that their overall resilience models can make sure that they are playing in the ‘bounce forward’ environment, so that they can achieve excellent outcomes over the long-term.

Executive Summary

The sixth workshop in the Simplified Wellness Program – Resilience – takes you on a deep dive into the topic of resilience so you can better understand what it truly is and the ways you can develop and use it to improve your experience of life.

Resilience is the process and result of overcoming difficult or demanding life situations, particularly through mental, emotional, and behavioral flexibility and adaptation to internal and external challenges.

How well people adapt to adversity depends on a number of elements, the most important of which are:

• the perspectives and interactions that people have with the world;

• the quantity and caliber of social resources; and

• particular coping mechanisms

Psychological studies have shown that the resources and abilities linked to more positive adaptation – that is, more resilience – aren’t necessarily inherited, but rather can be developed and practiced.

This module takes you on a deep dive into the topic of resilience so you can better understand what it truly is and the ways you can develop and use it to improve your experience of life.

This workshop has 12 focus areas. Here’s what they cover:

Chapter 1: What is Resilience?

Resilience has become something of a buzzword in recent times, with it being touted as a solution to many of the stress, exhaustion and burnout issues that individuals around the globe are facing in growing numbers.

But resilience is so much more than the watered-down message that is being provided around the world. There are many facets to this topic that are well worth understanding so that real solutions can be built to help individuals and organizations deal with the issues they are facing.

In this focus area you will look at what resilience is and why it is important to have it.

Chapter 2: History of Resilience

To most people, resilience is a relatively new term that has come to the forefront through the ‘resilience training’ industry that has grown around the stress, exhaustion and burnout issues being experienced by organizations around the world.

Resilience itself has a history that stems back to the 19th Century and has morphed from being used in materials and science to its current application as a concept for comprehending how society might react to challenges threatening individuals, communities, organizations, and nations more effectively.

In this focus area you will look at where resilience came from and how it has developed over time.

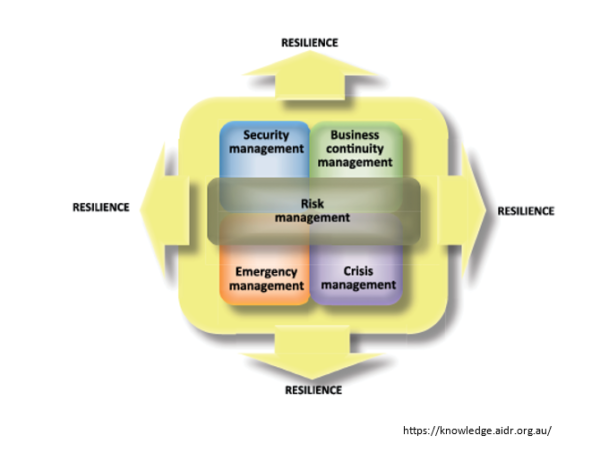

Chapter 3: Resilient Businesses

The level of change and business risk in the world is unprecedented in recent generations. While some businesses stagnate and fail, others evolve, develop, and even succeed. Resilience is the difference.

Today’s corporate climate is becoming more dynamic and unpredictable, making resilience more crucial.

This is due to a number of enduring pressures that are straining and stretching business systems, including increased global economic interconnection, quicker technological advancement, and more general challenges like rising inequality, species extinction, and climate change.

In this focus area you will look at what a resilient business looks like and what characteristics they have in common with each other.

Chapter 4: Resilient People

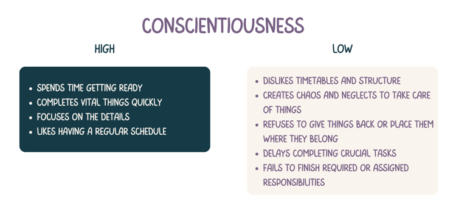

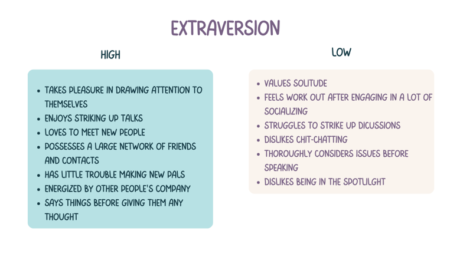

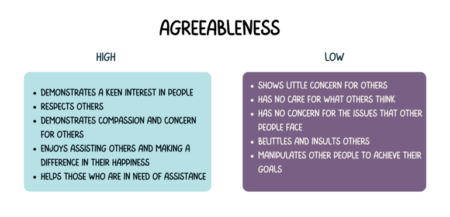

How does someone become resilient? Resilient behavior can be influenced by a variety of variables, such as personality traits, upbringing, genetics, environmental conditions, and social support.

Learning about the traits of resilient people, and when and how to ask for assistance in developing resilience, makes sense if you want to know more about becoming more resilient.

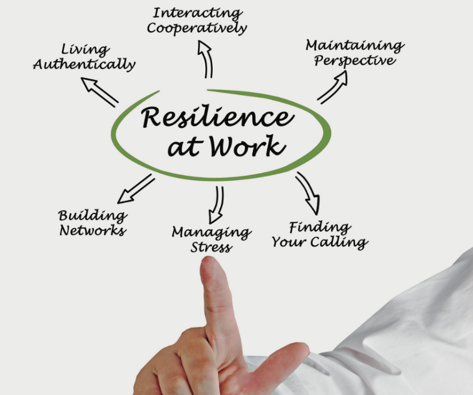

A resilient individual typically possesses awareness, self-control, problem-solving abilities, and social support. People that are resilient are conscious of their surroundings, their feelings, and the actions of those around them.

This focus area looks at what the traits and qualities of resilient people look like and what makes some people more resilient than others.

Chapter 5: Cognitive Resilience

Researchers say that building cognitive resilience, can help you maintain the mental agility and memory retention of someone who is decades younger.

In addition, research has shown that even people with severe brain changes (such as people suffering from diseases such as Alzheimer’s) can delay cognitive decline by building up cognitive resilience.

Ultimately, deliberately developing cognitive resilience allows our brain to develop a capacity to withstand, prevent or recover from illness, trauma and hardship more easily, and with today’s way of life that is a powerful ally to have in your tool kit.

In this focus area you’ll learn more about what cognitive resilience is, how it is useful and how you build more of it in your life.

Chapter 6: Physical Resilience

Physical resilience is the ability of the body to respond to new challenges, maintain strength and endurance under pressure, and recover quickly and effectively after acute injury or microbial invasion.

But it is made more difficult by a wide range of cultural and environmental factors, chief among which is how distant we have become from our own bodies.

In this focus area you’ll look at what physical resilience is, the impact on organizations when you get it wrong and the ways that sleep and stress impact it.

Chapter 7: Emotional Resilience

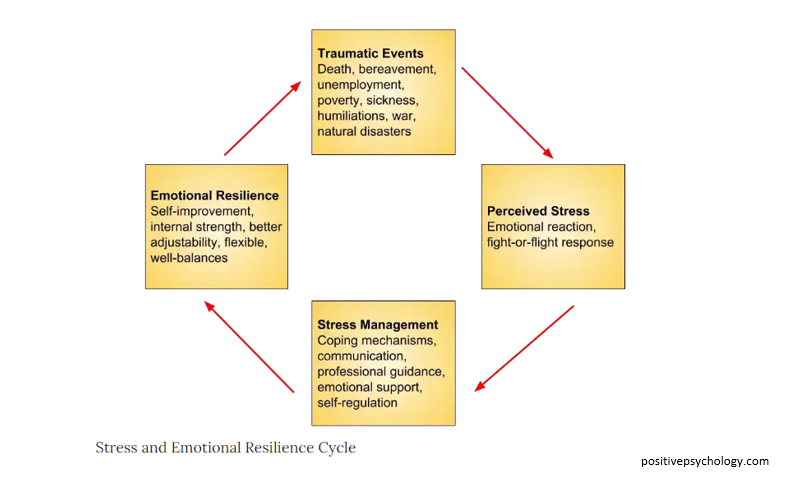

When you can control your agitated thoughts after having a bad event, you have emotional resilience. It is the innate motivation, a power within us, that enables us to endure all of life’s challenges.

Emotional resilience is a feature that exists from birth and keeps growing throughout life, just like other facets of our identity like social intelligence and emotional intelligence.

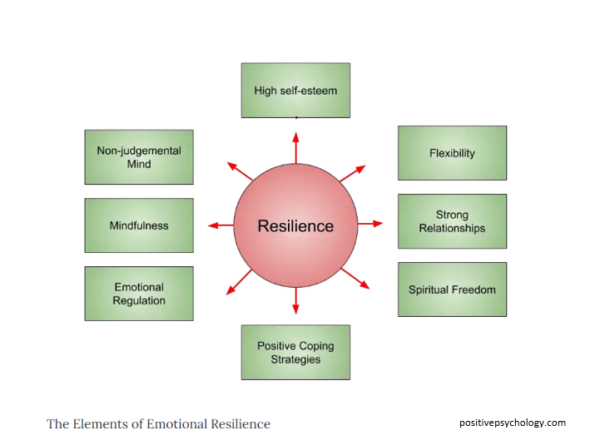

In this area you’ll explore the role of emotional resilience and what low levels of emotional resilience in individuals looks like.

Chapter 8: Psychological Resilience

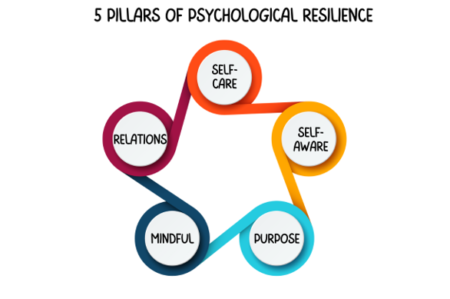

Psychological resilience is the capacity to quickly recover from a crisis, or deal with it intellectually and emotionally.

An individual’s level of resilience is influenced by a variety of variables.

Personal traits like self-esteem, self-control, and a good view of life are examples of internal variables. Social support networks, such as those with family, friends, and the community, as well as access to resources and opportunities, are examples of external variables.

In this focus area you’ll explore what social resilience is, its importance in life and the ways that it can be built within individuals and communities.

Chapter 9: Social Resilience

Social resilience is the ability of social groupings and communities to react positively to and/or bounce back from setbacks or crises as they occur.

Disasters are now experienced by the general population in ways that have never been seen before. When community resilience is strong, the collective works together in a more cohesive way which makes it easier for an organization to weather the storm that comes with significant challenges.

In this focus area you’ll look explore what social resilience is, its importance in life and ways that it can be built within individuals and communities.

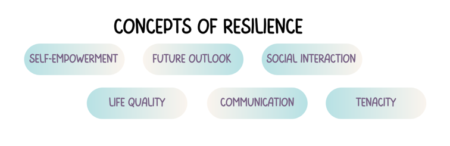

Chapter 10: Concepts of Resilience

Numerous resilience experts say that the cornerstone of resilience is made up of six fundamental abilities or competencies: self-awareness, self-control, optimism, mental agility, qualities of character and connection.

These competencies have the power to enrich one’s life, deepen relationships with others, and really just widen the scope of their universe and help them discover more meaning and purpose.

The six concepts of resilience is based on the principle that even those who lack resiliency naturally can develop the necessary abilities to develop it within themselves.

In this focus area you’ll look at the six concepts of resilience and as well as the four dimensions that individuals need to build personal resilience.

Chapter 11: Resilience Scales

Depending on who you ask, resilience is defined differently.

Psychology experts may have one (or several) definitions, while individuals who interact closely with people who are struggling frequently have a different perspective.

Because every individual is unique, it is easy to see that there would need to be numerous approaches to defining and measuring resilience when considering the numerous distinct components that make up the resilience machine. Resilience has been described in a practically infinite number of ways, and therefore there a number of different scales that have been developed to help measure resilience levels within individuals, organizations and communities.

In this focus area you will look at the way that eight different scales can be used to measure resilience levels in individuals, communities and organizations.

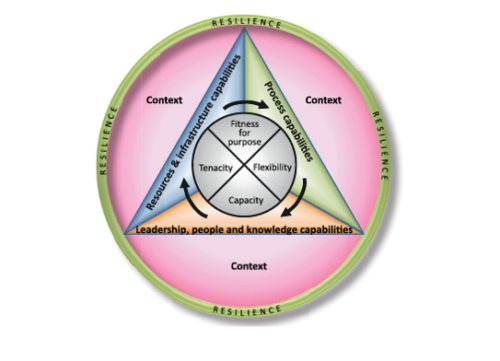

Chapter 12: Models of Resilience

Life is not always ideal. Even though we would all like for things to ‘just go our way’ all of the time, challenges are unavoidable and must be faced by everyone.

According to resilience theory, how we respond to adversity, rather than its actual characteristics, is what matters most. Resilience not only aids in our ability to endure, bounce back from, and even flourish after adversity, but is also aids us in overcoming hardship, bad luck, or irritation.

In this focus area you’ll understand the models of resilience and the way that resilience theory is defined.

Curriculum

Simplified Wellness– Workshop 6 – Resilience & Work-Life Balance

- What is Resilience

- History of Resilience

- Resilient Businesses

- Resilient People

- Cognitive Resilience

- Physical Resilience

- Emotional Resilience

- Psychological Resilience

- Social Resilience

- Concepts of Resilience

- Resilience Scales

- Models of Resilience

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Simplified Wellness corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast

As a guide, the Appleton Greene Simplified Wellness corporate training program should take 12-18 months to complete, depending upon your availability and current commitments. The reason why there is such a variance in time estimates is because every student is an individual, with differing productivity levels and different commitments. These differentiations are then exaggerated by the fact that this is a distance-learning program, which incorporates the practical integration of academic theory as an as a part of the training program. Consequently all of the project studies are real, which means that important decisions and compromises need to be made. You will want to get things right and will need to be patient with your expectations in order to ensure that they are. We would always recommend that you are prudent with your own task and time forecasts, but you still need to develop them and have a clear indication of what are realistic expectations in your case. With reference to your time planning: consider the time that you can realistically dedicate towards study with the program every week; calculate how long it should take you to complete the program, using the guidelines featured here; then break the program down into logical modules and allocate a suitable proportion of time to each of them, these will be your milestones; you can create a time plan by using a spreadsheet on your computer, or a personal organizer such as MS Outlook, you could also use a financial forecasting software; break your time forecasts down into manageable chunks of time, the more specific you can be, the more productive and accurate your time management will be; finally, use formulas where possible to do your time calculations for you, because this will help later on when your forecasts need to change in line with actual performance. With reference to your task planning: refer to your list of tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve your program objectives; with reference to your time plan, calculate when each task should be implemented; remember that you are not estimating when your objectives will be achieved, but when you will need to focus upon implementing the corresponding tasks; you also need to ensure that each task is implemented in conjunction with the associated training modules which are relevant; then break each single task down into a list of specific to do’s, say approximately ten to do’s for each task and enter these into your study plan; once again you could use MS Outlook to incorporate both your time and task planning and this could constitute your study plan; you could also use a project management software like MS Project. You should now have a clear and realistic forecast detailing when you can expect to be able to do something about undertaking the tasks to achieve your program objectives.

Performance management

It is one thing to develop your study forecast, it is quite another to monitor your progress. Ultimately it is less important whether you achieve your original study forecast and more important that you update it so that it constantly remains realistic in line with your performance. As you begin to work through the program, you will begin to have more of an idea about your own personal performance and productivity levels as a distance-learner. Once you have completed your first study module, you should re-evaluate your study forecast for both time and tasks, so that they reflect your actual performance level achieved. In order to achieve this you must first time yourself while training by using an alarm clock. Set the alarm for hourly intervals and make a note of how far you have come within that time. You can then make a note of your actual performance on your study plan and then compare your performance against your forecast. Then consider the reasons that have contributed towards your performance level, whether they are positive or negative and make a considered adjustment to your future forecasts as a result. Given time, you should start achieving your forecasts regularly.

With reference to time management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual time taken in your study plan; consider your successes with time-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; consider your failures with time-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to time planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your time expectations. You need to be consistent with your time management, otherwise you will never complete your studies. This will either be because you are not contributing enough time to your studies, or you will become less efficient with the time that you do allocate to your studies. Remember, if you are not in control of your studies, they can just become yet another cause of stress for you.

With reference to your task management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual tasks that you have undertaken in your study plan; consider your successes with task-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case; take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; consider your failures with task-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to task planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your task expectations. You need to be consistent with your task management, otherwise you will never know whether you are achieving your program objectives or not.

Keeping in touch

You will have access to qualified and experienced professors and tutors who are responsible for providing tutorial support for your particular training program. So don’t be shy about letting them know how you are getting on. We keep electronic records of all tutorial support emails so that professors and tutors can review previous correspondence before considering an individual response. It also means that there is a record of all communications between you and your professors and tutors and this helps to avoid any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation. If you have a problem relating to the program, share it with them via email. It is likely that they have come across the same problem before and are usually able to make helpful suggestions and steer you in the right direction. To learn more about when and how to use tutorial support, please refer to the Tutorial Support section of this student information guide. This will help you to ensure that you are making the most of tutorial support that is available to you and will ultimately contribute towards your success and enjoyment with your training program.

Work colleagues and family

You should certainly discuss your program study progress with your colleagues, friends and your family. Appleton Greene training programs are very practical. They require you to seek information from other people, to plan, develop and implement processes with other people and to achieve feedback from other people in relation to viability and productivity. You will therefore have plenty of opportunities to test your ideas and enlist the views of others. People tend to be sympathetic towards distance-learners, so don’t bottle it all up in yourself. Get out there and share it! It is also likely that your family and colleagues are going to benefit from your labors with the program, so they are likely to be much more interested in being involved than you might think. Be bold about delegating work to those who might benefit themselves. This is a great way to achieve understanding and commitment from people who you may later rely upon for process implementation. Share your experiences with your friends and family.

Making it relevant

The key to successful learning is to make it relevant to your own individual circumstances. At all times you should be trying to make bridges between the content of the program and your own situation. Whether you achieve this through quiet reflection or through interactive discussion with your colleagues, client partners or your family, remember that it is the most important and rewarding aspect of translating your studies into real self-improvement. You should be clear about how you want the program to benefit you. This involves setting clear study objectives in relation to the content of the course in terms of understanding, concepts, completing research or reviewing activities and relating the content of the modules to your own situation. Your objectives may understandably change as you work through the program, in which case you should enter the revised objectives on your study plan so that you have a permanent reminder of what you are trying to achieve, when and why.

Distance-learning check-list

Prepare your study environment, your study tools and rules.

Undertake detailed self-assessment in terms of your ability as a learner.

Create a format for your study plan.

Consider your study objectives and tasks.

Create a study forecast.

Assess your study performance.

Re-evaluate your study forecast.

Be consistent when managing your study plan.

Use your Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) for tutorial support.

Make sure you keep in touch with those around you.

Tutorial Support

Programs

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. They are implemented over a sustainable period of time and professional support is consistently provided by qualified learning providers and specialist consultants.

Support available

You will have a designated Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and an Accredited Consultant and we encourage you to communicate with them as much as possible. In all cases tutorial support is provided online because we can then keep a record of all communications to ensure that tutorial support remains consistent. You would also be forwarding your work to the tutorial support unit for evaluation and assessment. You will receive individual feedback on all of the work that you undertake on a one-to-one basis, together with specific recommendations for anything that may need to be changed in order to achieve a pass with merit or a pass with distinction and you then have as many opportunities as you may need to re-submit project studies until they meet with the required standard. Consequently the only reason that you should really fail (CLP) is if you do not do the work. It makes no difference to us whether a student takes 12 months or 18 months to complete the program, what matters is that in all cases the same quality standard will have been achieved.

Support Process

Please forward all of your future emails to the designated (CLP) Tutorial Support Unit email address that has been provided and please do not duplicate or copy your emails to other AGC email accounts as this will just cause unnecessary administration. Please note that emails are always answered as quickly as possible but you will need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general tutorial support emails during busy periods, because emails are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. You will also need to allow a period of up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Please therefore kindly allow for this within your time planning. All communications are managed online via email because it enables tutorial service support managers to review other communications which have been received before responding and it ensures that there is a copy of all communications retained on file for future reference. All communications will be stored within your personal (CLP) study file here at Appleton Greene throughout your designated study period. If you need any assistance or clarification at any time, please do not hesitate to contact us by forwarding an email and remember that we are here to help. If you have any questions, please list and number your questions succinctly and you can then be sure of receiving specific answers to each and every query.

Time Management

It takes approximately 1 Year to complete the Simplified Wellness corporate training program, incorporating 12 x 6-hour monthly workshops. Each student will also need to contribute approximately 4 hours per week over 1 Year of their personal time. Students can study from home or work at their own pace and are responsible for managing their own study plan. There are no formal examinations and students are evaluated and assessed based upon their project study submissions, together with the quality of their internal analysis and supporting documents. They can contribute more time towards study when they have the time to do so and can contribute less time when they are busy. All students tend to be in full time employment while studying and the Simplified Wellness program is purposely designed to accommodate this, so there is plenty of flexibility in terms of time management. It makes no difference to us at Appleton Greene, whether individuals take 12-18 months to complete this program. What matters is that in all cases the same standard of quality will have been achieved with the standard and bespoke programs that have been developed.

Distance Learning Guide

The distance learning guide should be your first port of call when starting your training program. It will help you when you are planning how and when to study, how to create the right environment and how to establish the right frame of mind. If you can lay the foundations properly during the planning stage, then it will contribute to your enjoyment and productivity while training later. The guide helps to change your lifestyle in order to accommodate time for study and to cultivate good study habits. It helps you to chart your progress so that you can measure your performance and achieve your goals. It explains the tools that you will need for study and how to make them work. It also explains how to translate academic theory into practical reality. Spend some time now working through your distance learning guide and make sure that you have firm foundations in place so that you can make the most of your distance learning program. There is no requirement for you to attend training workshops or classes at Appleton Greene offices. The entire program is undertaken online, program course manuals and project studies are administered via the Appleton Greene web site and via email, so you are able to study at your own pace and in the comfort of your own home or office as long as you have a computer and access to the internet.

How To Study

The how to study guide provides students with a clear understanding of the Appleton Greene facilitation via distance learning training methods and enables students to obtain a clear overview of the training program content. It enables students to understand the step-by-step training methods used by Appleton Greene and how course manuals are integrated with project studies. It explains the research and development that is required and the need to provide evidence and references to support your statements. It also enables students to understand precisely what will be required of them in order to achieve a pass with merit and a pass with distinction for individual project studies and provides useful guidance on how to be innovative and creative when developing your Unique Program Proposition (UPP).

Tutorial Support

Tutorial support for the Appleton Greene Simplified Wellness corporate training program is provided online either through the Appleton Greene Client Support Portal (CSP), or via email. All tutorial support requests are facilitated by a designated Program Administration Manager (PAM). They are responsible for deciding which professor or tutor is the most appropriate option relating to the support required and then the tutorial support request is forwarded onto them. Once the professor or tutor has completed the tutorial support request and answered any questions that have been asked, this communication is then returned to the student via email by the designated Program Administration Manager (PAM). This enables all tutorial support, between students, professors and tutors, to be facilitated by the designated Program Administration Manager (PAM) efficiently and securely through the email account. You will therefore need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general support queries and up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies, because all tutorial support requests are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Consequently you need to put some thought into the management of your tutorial support procedure in order to ensure that your study plan is feasible and to obtain the maximum possible benefit from tutorial support during your period of study. Please retain copies of your tutorial support emails for future reference. Please ensure that ALL of your tutorial support emails are set out using the format as suggested within your guide to tutorial support. Your tutorial support emails need to be referenced clearly to the specific part of the course manual or project study which you are working on at any given time. You also need to list and number any questions that you would like to ask, up to a maximum of five questions within each tutorial support email. Remember the more specific you can be with your questions the more specific your answers will be too and this will help you to avoid any unnecessary misunderstanding, misinterpretation, or duplication. The guide to tutorial support is intended to help you to understand how and when to use support in order to ensure that you get the most out of your training program. Appleton Greene training programs are designed to enable you to do things for yourself. They provide you with a structure or a framework and we use tutorial support to facilitate students while they practically implement what they learn. In other words, we are enabling students to do things for themselves. The benefits of distance learning via facilitation are considerable and are much more sustainable in the long-term than traditional short-term knowledge sharing programs. Consequently you should learn how and when to use tutorial support so that you can maximize the benefits from your learning experience with Appleton Greene. This guide describes the purpose of each training function and how to use them and how to use tutorial support in relation to each aspect of the training program. It also provides useful tips and guidance with regard to best practice.

Tutorial Support Tips

Students are often unsure about how and when to use tutorial support with Appleton Greene. This Tip List will help you to understand more about how to achieve the most from using tutorial support. Refer to it regularly to ensure that you are continuing to use the service properly. Tutorial support is critical to the success of your training experience, but it is important to understand when and how to use it in order to maximize the benefit that you receive. It is no coincidence that those students who succeed are those that learn how to be positive, proactive and productive when using tutorial support.

Be positive and friendly with your tutorial support emails

Remember that if you forward an email to the tutorial support unit, you are dealing with real people. “Do unto others as you would expect others to do unto you”. If you are positive, complimentary and generally friendly in your emails, you will generate a similar response in return. This will be more enjoyable, productive and rewarding for you in the long-term.

Think about the impression that you want to create

Every time that you communicate, you create an impression, which can be either positive or negative, so put some thought into the impression that you want to create. Remember that copies of all tutorial support emails are stored electronically and tutors will always refer to prior correspondence before responding to any current emails. Over a period of time, a general opinion will be arrived at in relation to your character, attitude and ability. Try to manage your own frustrations, mood swings and temperament professionally, without involving the tutorial support team. Demonstrating frustration or a lack of patience is a weakness and will be interpreted as such. The good thing about communicating in writing, is that you will have the time to consider your content carefully, you can review it and proof-read it before sending your email to Appleton Greene and this should help you to communicate more professionally, consistently and to avoid any unnecessary knee-jerk reactions to individual situations as and when they may arise. Please also remember that the CLP Tutorial Support Unit will not just be responsible for evaluating and assessing the quality of your work, they will also be responsible for providing recommendations to other learning providers and to client contacts within the Appleton Greene global client network, so do be in control of your own emotions and try to create a good impression.

Remember that quality is preferred to quantity

Please remember that when you send an email to the tutorial support team, you are not using Twitter or Text Messaging. Try not to forward an email every time that you have a thought. This will not prove to be productive either for you or for the tutorial support team. Take time to prepare your communications properly, as if you were writing a professional letter to a business colleague and make a list of queries that you are likely to have and then incorporate them within one email, say once every month, so that the tutorial support team can understand more about context, application and your methodology for study. Get yourself into a consistent routine with your tutorial support requests and use the tutorial support template provided with ALL of your emails. The (CLP) Tutorial Support Unit will not spoon-feed you with information. They need to be able to evaluate and assess your tutorial support requests carefully and professionally.

Be specific about your questions in order to receive specific answers

Try not to write essays by thinking as you are writing tutorial support emails. The tutorial support unit can be unclear about what in fact you are asking, or what you are looking to achieve. Be specific about asking questions that you want answers to. Number your questions. You will then receive specific answers to each and every question. This is the main purpose of tutorial support via email.

Keep a record of your tutorial support emails

It is important that you keep a record of all tutorial support emails that are forwarded to you. You can then refer to them when necessary and it avoids any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation.

Individual training workshops or telephone support

Tutorial Support Email Format

You should use this tutorial support format if you need to request clarification or assistance while studying with your training program. Please note that ALL of your tutorial support request emails should use the same format. You should therefore set up a standard email template, which you can then use as and when you need to. Emails that are forwarded to Appleton Greene, which do not use the following format, may be rejected and returned to you by the (CLP) Program Administration Manager. A detailed response will then be forwarded to you via email usually within 20 business days of receipt for general support queries and 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Your tutorial support request, together with the corresponding TSU reply, will then be saved and stored within your electronic TSU file at Appleton Greene for future reference.

Subject line of your email

Please insert: Appleton Greene (CLP) Tutorial Support Request: (Your Full Name) (Date), within the subject line of your email.

Main body of your email

Please insert:

1. Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) Tutorial Support Request

2. Your Full Name

3. Date of TS request

4. Preferred email address

5. Backup email address

6. Course manual page name or number (reference)

7. Project study page name or number (reference)

Subject of enquiry

Please insert a maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Briefly outline the subject matter of your inquiry, or what your questions relate to.

Question 1

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Question 3

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Question 4

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Question 5

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Please note that a maximum of 5 questions is permitted with each individual tutorial support request email.

Procedure

* List the questions that you want to ask first, then re-arrange them in order of priority. Make sure that you reference them, where necessary, to the course manuals or project studies.

* Make sure that you are specific about your questions and number them. Try to plan the content within your emails to make sure that it is relevant.

* Make sure that your tutorial support emails are set out correctly, using the Tutorial Support Email Format provided here.

* Save a copy of your email and incorporate the date sent after the subject title. Keep your tutorial support emails within the same file and in date order for easy reference.

* Allow up to 20 business days for a response to general tutorial support emails and up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies, because detailed individual responses will be made in all cases and tutorial support emails are answered strictly within the order in which they are received.

* Emails can and do get lost. So if you have not received a reply within the appropriate time, forward another copy or a reminder to the tutorial support unit to be sure that it has been received but do not forward reminders unless the appropriate time has elapsed.

* When you receive a reply, save it immediately featuring the date of receipt after the subject heading for easy reference. In most cases the tutorial support unit replies to your questions individually, so you will have a record of the questions that you asked as well as the answers offered. With project studies however, separate emails are usually forwarded by the tutorial support unit, so do keep a record of your own original emails as well.

* Remember to be positive and friendly in your emails. You are dealing with real people who will respond to the same things that you respond to.

* Try not to repeat questions that have already been asked in previous emails. If this happens the tutorial support unit will probably just refer you to the appropriate answers that have already been provided within previous emails.

* If you lose your tutorial support email records you can write to Appleton Greene to receive a copy of your tutorial support file, but a separate administration charge may be levied for this service.

How To Study

Your Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and Accredited Consultant can help you to plan a task list for getting started so that you can be clear about your direction and your priorities in relation to your training program. It is also a good way to introduce yourself to the tutorial support team.

Planning your study environment

Your study conditions are of great importance and will have a direct effect on how much you enjoy your training program. Consider how much space you will have, whether it is comfortable and private and whether you are likely to be disturbed. The study tools and facilities at your disposal are also important to the success of your distance-learning experience. Your tutorial support unit can help with useful tips and guidance, regardless of your starting position. It is important to get this right before you start working on your training program.

Planning your program objectives

It is important that you have a clear list of study objectives, in order of priority, before you start working on your training program. Your tutorial support unit can offer assistance here to ensure that your study objectives have been afforded due consideration and priority.

Planning how and when to study

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. This approach is designed to let you study efficiently away from the traditional classroom environment. It is important however, that you plan how and when to study, so that you are making the most of your natural attributes, strengths and opportunities. Your tutorial support unit can offer assistance and useful tips to ensure that you are playing to your strengths.

Planning your study tasks

You should have a clear understanding of the study tasks that you should be undertaking and the priority associated with each task. These tasks should also be integrated with your program objectives. The distance learning guide and the guide to tutorial support for students should help you here, but if you need any clarification or assistance, please contact your tutorial support unit.

Planning your time

You will need to allocate specific times during your calendar when you intend to study if you are to have a realistic chance of completing your program on time. You are responsible for planning and managing your own study time, so it is important that you are successful with this. Your tutorial support unit can help you with this if your time plan is not working.

Keeping in touch

Consistency is the key here. If you communicate too frequently in short bursts, or too infrequently with no pattern, then your management ability with your studies will be questioned, both by you and by your tutorial support unit. It is obvious when a student is in control and when one is not and this will depend how able you are at sticking with your study plan. Inconsistency invariably leads to in-completion.

Charting your progress

Your tutorial support team can help you to chart your own study progress. Refer to your distance learning guide for further details.

Making it work

To succeed, all that you will need to do is apply yourself to undertaking your training program and interpreting it correctly. Success or failure lies in your hands and your hands alone, so be sure that you have a strategy for making it work. Your Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and Accredited Consultant can guide you through the process of program planning, development and implementation.

Reading methods

Interpretation is often unique to the individual but it can be improved and even quantified by implementing consistent interpretation methods. Interpretation can be affected by outside interference such as family members, TV, or the Internet, or simply by other thoughts which are demanding priority in our minds. One thing that can improve our productivity is using recognized reading methods. This helps us to focus and to be more structured when reading information for reasons of importance, rather than relaxation.

Speed reading

When reading through course manuals for the first time, subconsciously set your reading speed to be just fast enough that you cannot dwell on individual words or tables. With practice, you should be able to read an A4 sheet of paper in one minute. You will not achieve much in the way of a detailed understanding, but your brain will retain a useful overview. This overview will be important later on and will enable you to keep individual issues in perspective with a more generic picture because speed reading appeals to the memory part of the brain. Do not worry about what you do or do not remember at this stage.

Content reading

Once you have speed read everything, you can then start work in earnest. You now need to read a particular section of your course manual thoroughly, by making detailed notes while you read. This process is called Content Reading and it will help to consolidate your understanding and interpretation of the information that has been provided.

Making structured notes on the course manuals

When you are content reading, you should be making detailed notes, which are both structured and informative. Make these notes in a MS Word document on your computer, because you can then amend and update these as and when you deem it to be necessary. List your notes under three headings: 1. Interpretation – 2. Questions – 3. Tasks. The purpose of the 1st section is to clarify your interpretation by writing it down. The purpose of the 2nd section is to list any questions that the issue raises for you. The purpose of the 3rd section is to list any tasks that you should undertake as a result. Anyone who has graduated with a business-related degree should already be familiar with this process.

Organizing structured notes separately

You should then transfer your notes to a separate study notebook, preferably one that enables easy referencing, such as a MS Word Document, a MS Excel Spreadsheet, a MS Access Database, or a personal organizer on your cell phone. Transferring your notes allows you to have the opportunity of cross-checking and verifying them, which assists considerably with understanding and interpretation. You will also find that the better you are at doing this, the more chance you will have of ensuring that you achieve your study objectives.

Question your understanding

Do challenge your understanding. Explain things to yourself in your own words by writing things down.

Clarifying your understanding

If you are at all unsure, forward an email to your tutorial support unit and they will help to clarify your understanding.

Question your interpretation

Do challenge your interpretation. Qualify your interpretation by writing it down.

Clarifying your interpretation

If you are at all unsure, forward an email to your tutorial support unit and they will help to clarify your interpretation.

Qualification Requirements

The student will need to successfully complete the project study and all of the exercises relating to the Simplified Wellness corporate training program, achieving a pass with merit or distinction in each case, in order to qualify as an Accredited Simplified Wellness Specialist (APTS). All monthly workshops need to be tried and tested within your company. These project studies can be completed in your own time and at your own pace and in the comfort of your own home or office. There are no formal examinations, assessment is based upon the successful completion of the project studies. They are called project studies because, unlike case studies, these projects are not theoretical, they incorporate real program processes that need to be properly researched and developed. The project studies assist us in measuring your understanding and interpretation of the training program and enable us to assess qualification merits. All of the project studies are based entirely upon the content within the training program and they enable you to integrate what you have learnt into your corporate training practice.

Simplified Wellness – Grading Contribution

Project Study – Grading Contribution

Customer Service – 10%

E-business – 05%

Finance – 10%

Globalization – 10%

Human Resources – 10%

Information Technology – 10%

Legal – 05%

Management – 10%

Marketing – 10%

Production – 10%

Education – 05%

Logistics – 05%

TOTAL GRADING – 100%

Qualification grades

A mark of 90% = Pass with Distinction.

A mark of 75% = Pass with Merit.

A mark of less than 75% = Fail.

If you fail to achieve a mark of 75% with a project study, you will receive detailed feedback from the Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and/or Accredited Consultant, together with a list of tasks which you will need to complete, in order to ensure that your project study meets with the minimum quality standard that is required by Appleton Greene. You can then re-submit your project study for further evaluation and assessment. Indeed you can re-submit as many drafts of your project studies as you need to, until such a time as they eventually meet with the required standard by Appleton Greene, so you need not worry about this, it is all part of the learning process.

When marking project studies, Appleton Greene is looking for sufficient evidence of the following:

Pass with merit

A satisfactory level of program understanding

A satisfactory level of program interpretation

A satisfactory level of project study content presentation

A satisfactory level of Unique Program Proposition (UPP) quality

A satisfactory level of the practical integration of academic theory

Pass with distinction

An exceptional level of program understanding

An exceptional level of program interpretation

An exceptional level of project study content presentation

An exceptional level of Unique Program Proposition (UPP) quality

An exceptional level of the practical integration of academic theory

Preliminary Analysis

Articles on Post Traumatic Mental Health:

Using brief app-based mindfulness intervention on psychosocial outcomes in healthy adults:

Improvement in stress, affect and irritability following brief use of mindfulness-based smartphone apps:

Modifying resilience mechanisms in at risk individuals:

United Nations Common Guidance on Helping Build Resilient Societies:

Course Manuals 1-12

Course Manual 1: What is Resilience?

Introduction

The business environment of today has undergone a significant transformation, as corporate executives understand the value of long-term brand development and sustainable growth over short-term profit maximization.

There are always internal and external factors that create challenges. With the speed that technology develops, barriers to entry falling and people becoming more educated, the challenges that organizations and their people face increase rapidly as well.

In the past decades the world has experienced epidemics, a pandemic, supply chain disruptions, a deluge of natural disasters, political turmoil, rampant retail crime, and economic uncertainty. It has become clear to many corporate leaders that unprecedented upheaval is the new normal, and there is no turning back in the face of these mounting challenges.

In order to meet their brand promises, successful organizations must invest in the tools and procedures necessary to analyze their capacity for shock absorption and proactively reduce interruptions.

Dexterous leaders have stepped into actively creating methods to aid in their increased agility, and greater ability to adapt and respond to unforeseen disruptions as well as long-term challenges.

Extensive initiatives for sustainability and resilience go way beyond corporate governance. In order to bolster their competitive advantage in the upcoming years, executives are carefully investing in understanding what being resilient really means, and then providing themselves with the tools and resources to arm their people to thrive in challenging situations.

During and even after challenges arise, the competitive environment for many organizations undergoes a significant transformation. Whether it be changes to people’s interactions with physical sites, the mix of in person versus online purchasing, changes to travel means and modes, or changes to employee or customer expectations, organizations and their people need to be nimble enough to move with what changes need to be made during and after challenges arise.

Companies who are able to foresee these changing market demands are better able to meet new wants before their rivals. It is also true that organizations with high levels of resilience will be best placed to create opportunities from challenges that present.

What is resilience?

When we talk about resilience, we are often referring to resilience within individuals, but there are many forms of resilience and it is important to understand their role and the ways in which they impact an organization’s ability to move with challenges as they arise.

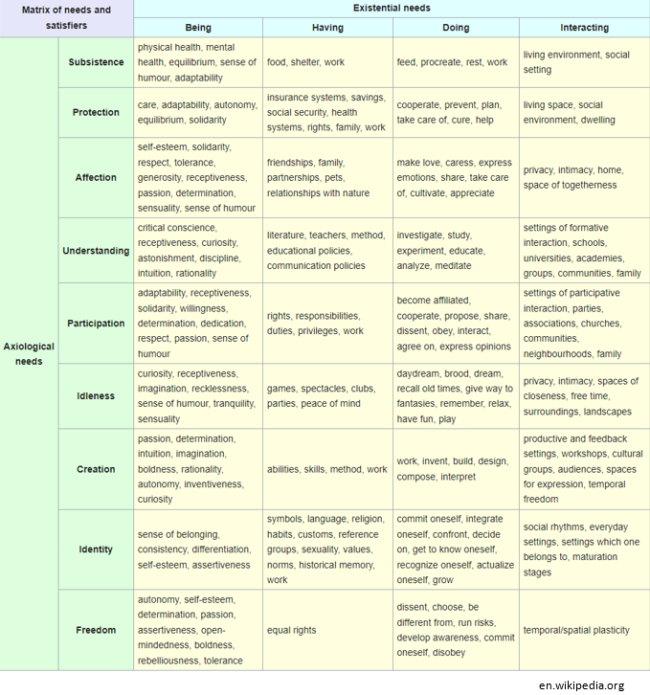

Wikipedia tells us that resilience is:

1. (psychology, neuroscience) The mental ability to recover quickly from depression, illness or misfortune.

2. (physics) The physical property of material that can resume its shape after being stretched or deformed; elasticity.

3. The positive capacity of an organizational system or company to adapt and return to equilibrium after a crisis, failure or any kind of disruption, including: an outage, natural disasters, man-made disasters, terrorism, or similar (particularly IT systems, archives).

4. The capacity to resist destruction or defeat, especially when under extreme pressure.

So, you can see that resilience can apply to people, materials and/or organizations but that ultimately the ‘capacity to resist destruction or defeat, especially when under extreme pressure’ can be applied to each area.