Cultivating Potential – Workshop 2 (Growth Foundation)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Cultivating Potential is provided by Mr. Biss MRED Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Mr. Biss, MRED, is a Certified Learning Provider (CLP) at Appleton Greene. He has experience in management, marketing, and operations. He has a degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Maryland and a Masters of Real Estate Development from Auburn University.

He has industry experience in the following sectors: Non-profit & Charities, Real Estate, Defense, Aviation and Aerospace.

He has had commercial experience in the following countries: United States of America, or more specifically within the following cities: Washington DC, Atlanta GA, Charlotte NC, Orlando FL, and Raleigh NC.

In addition to serving as a KC-130J Transport Plane Commander during global operations throughout North America, Europe, and the Middle East, he served in leadership positions in aviation operations, quality assurance, and maintenance. During one role as a maintenance division officer, he was responsible for the maintenance of a $400MM fleet of aircraft and the leadership of 100 personnel.

Upon retiring from the Marine Corps, Biss pivoted professionally to pursue aspirations in human potential development and has been involved in pioneering work to bring advances human potential development and positive psychology interventions to those in addiction recovery to help cultivate their higher potential for wellbeing and a life of meaning.

Additionally, he serves as a founding member of a water NGO, where he leads small teams into rural villages in Central America to deliver innovative water solutions, having served more than 50 communities so far providing safe water to nearly 12,000 water-insecure people.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

This second module shifts the focus from learning ideas to application and the Cultivating Potential process for personal transformation.

A growth foundation begins with helping participants to adopt a growth mindset. Too often, we fall prey to the false belief that we as individuals have fixed strengths, talents, and abilities. Recent neuroscience and positive psychology have shown that skills and abilities are not a fixed variable but can continue to develop throughout a person’s life. Adopting a growth mindset (the focus for this module) provides the context for tapping into innate abilities that have yet to be revealed and processing for honing skills, gaining knowledge, and developing habits that reinforce personal growth.

Once a growth mindset is adopted, the possibilities for increased performance and heightened achievement become near limitless. This change starts with learning to accept full responsibilities for our individual actions and the outcomes we experience in life. Shifting the locus of control over our outcomes to the thoughts, visions, and actions we can control is a personally liberating and incredibly empowering skill to develop. Participants will leverage new tools to analyze how they can best respond to events and circumstances to get the outcomes they seek, regardless of external factors that influence the situation.

By the end of this module, participants will be ready to give up old habits of complaining, blaming, and excuse-making to focus their attention on their personal ownership of the situation and the responses that will lead to constructive outcomes. Through process-oriented performance evaluations, leaders at every level will learn to promote a growth mindset in their team members and co-workers.

With sights set on what is possible with a proper growth foundation, any participant’s inclination to shy away from one’s most ambitious goals will be addressed through processing limiting beliefs. Too often, it is not one’s innate ability that limits their level of achievement as much as it is false beliefs about what is possible for that individual, team, or organization to achieve. These false beliefs become self-fulfilling prophecies as we as individuals or groups limit our expectations for future outcomes; our performance is governed to meet the falsely perceived limitation we hold.

Objectives

01. Growth Mindset: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Intention Sets the Course: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Three-Part Brain: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Basic Human Needs: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Self-Esteem & Self-Efficacy: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. PERMA Model of Human Flourishing: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Illness/Wellness Continuum: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Positivity-Focused: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Strengths-Based: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Cognitive Biases: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Limiting Beliefs: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Leadership: Process Feedback: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Growth Mindset: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Intention Sets the Course: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Three-Part Brain: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Basic Human Needs: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Self-Esteem & Self-Efficacy: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. PERMA Model of Human Flourishing: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Illness/Wellness Continuum: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Positivity-Focused: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Strengths-Based: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Cognitive Biases: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Limiting Beliefs: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Leadership: Process Feedback: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Growth Mindset.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Intention Sets the Course.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Three-Part Brain.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Basic Human Needs.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Self-Esteem & Self-Efficacy.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze PERMA Model of Human Flourishing.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Illness/Wellness Continuum.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Positivity-Focused.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Strengths-Based.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Cognitive Biases.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Limiting Beliefs.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Leadership: Process Feedback.

Introduction

This second module shifts the focus from learning ideas to application and the Cultivating Potential process for personal transformation.

A growth foundation begins with helping participants to adopt a growth mindset. Too often, we fall prey to the false belief that we as individuals have fixed strengths, talents, and abilities. Recent neuroscience and positive psychology have shown that skills and abilities are not a fixed variable but can continue to develop throughout a person’s life. Adopting a growth mindset (the focus for this module) provides the context for tapping into innate abilities that have yet to be revealed and processing for honing skills, gaining knowledge, and developing habits that reinforce personal growth.

Once a growth mindset is adopted, the possibilities for increased performance and heightened achievement become near limitless. This change starts with learning to accept full responsibilities for our individual actions and the outcomes we experience in life. Shifting the locus of control over our outcomes to the thoughts, visions, and actions we can control is a personally liberating and incredibly empowering skill to develop. Participants will leverage new tools to analyze how they can best respond to events and circumstances to get the outcomes they seek, regardless of external factors that influence the situation.

By the end of this module, participants will be ready to give up old habits of complaining, blaming, and excuse-making to focus their attention on their personal ownership of the situation and the responses that will lead to constructive outcomes. Through process-oriented performance evaluations, leaders at every level will learn to promote a growth mindset in their team members and co-workers.

With sights set on what is possible with a proper growth foundation, any participant’s inclination to shy away from one’s most ambitious goals will be addressed through processing limiting beliefs. Too often, it is not one’s innate ability that limits their level of achievement as much as it is false beliefs about what is possible for that individual, team, or organization to achieve. These false beliefs become self-fulfilling prophecies as we as individuals or groups limit our expectations for future outcomes; our performance is governed to meet the falsely perceived limitation we hold.

Growth Foundation: reaching your full potential

Many athletes have been predicted to be the next big thing over the years, but they have failed to live up to their full potential. Freddy Adu, for example, became the youngest athlete in America to sign a professional contract when he signed with D.C United of Major League Soccer at the age of 14 in 2004. (MLS). He was dubbed “the next Pele” since he was the youngest player to appear and score in the MLS. Many people thought he was going to be one of the best soccer players ever.

Let’s jump ahead 13 years. Is Freddy Adu considered one of the best soccer players in the world? Regrettably, no. Adu has played for ten different professional clubs in the ten years since his big money move to Benfica in 2007, and at the age of just 28, he is currently a ‘free agent’ and does not play for any club.

So, why didn’t Freddy Adu achieve the heights that everyone expected him to, and why do so many other athletes share his fate? One possibility is that some athletes lack the attitude required to reach their full potential and compete at the highest level. If that’s the case, what kind of mindset does a good athlete require?

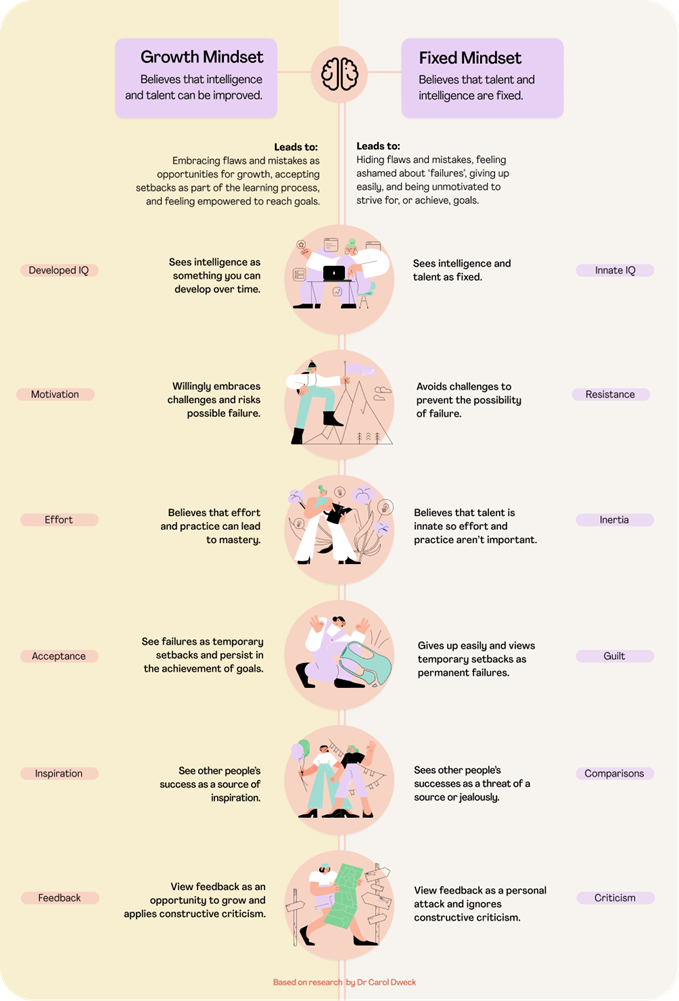

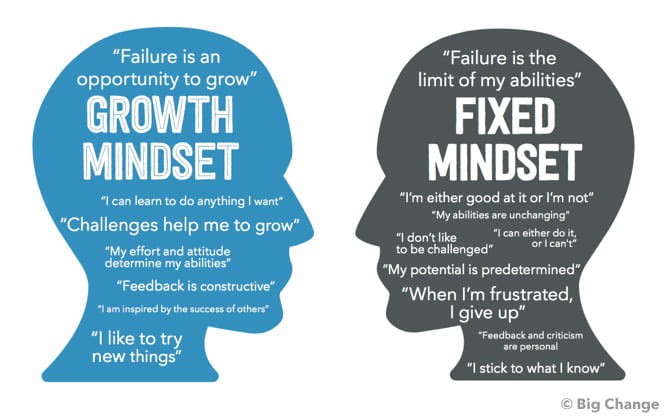

People have two types of mindsets, according to psychologist Carol Dweck: fixed and growth mindsets. Everyone will have both mindsets, but they will frequently favor one over the other.

Individuals with a fixed mindset believe that some characteristics, such as intelligence, talent, and athleticism, are unchangeable no matter what they do or try (Dweck, 2006, 2009). As a result, these people place a lower value on work and are more concerned with looking their best. People with a fixed mindset frequently fail to reach their full potential because they do not put in the necessary effort to achieve. Due to the fear of failure and looking stupid, research has consistently shown that people with a fixed mindset are more likely to give up easily when confronted with setbacks (Dweck, 2006, 2009). If you can’t succeed at something, they believe there’s no use in persevering since you simply lack the brains to succeed. This is frequently the reason why many young athletes with great potential fail to make the move to the next level.

People with a growth mindset believe that success and achievement are the result of a protracted process that requires hard work, dedication, and perseverance. They believe that talents and intelligence can be developed and improved through time, and that if they work hard enough, they can reach their full potential. According to research, cultivating a growth mindset can lead to good outcomes such as increased resilience in the face of adversity (Yeager & Dweck, 2012; Hinton & Hendrick, 2015), persistence for longer periods of time (Mueller & Dweck, 1998), and greater results (Dweck, 2008).

When examining the processes of the two mindset types, it’s easy to understand how Freddy Adu’s professional inability to achieve the heights anticipated of him might be related to a fixed mindset. His early professional success was sometimes attributed to his inherent ability and similarities to Pele, the Brazilian soccer legend. Hard work, commitment, and tenacity, on the other hand, were rarely mentioned as growth mindset behaviors. Freddy Adu may have developed a fixed mindset, believing his success was primarily due to his innate skill, as a result of the repeated praise on his ability. This research builds on Mueller and Dweck’s (1998) findings, which found that when students were commended for their intelligence/ability rather than their hard effort, their motivation and performance suffered.

According to research, having a growth mindset is a predictor of long-term success. The main question is: how can individuals learn to create growth mindset processes and boost their chances of reaching their maximum potential? The first step is to recognize that long-term success does not come solely from aptitude and ability. For example, was it easy to become a successful athlete, if you asked any elite athlete? They would argue no, claiming that high levels of work, perseverance, and a constant desire to learn are necessary factors for success. The following quotations from Michael Phelps (the most decorated Olympian) and Cristiano Ronaldo (the four-time world footballer of the year) illustrate the importance of trying to learn and progress at all times.

Michael Phelps: ‘There will be obstacles, there will be doubters, there will be mistakes. But with hard work, there are no limits’.

Cristiano Ronaldo: ‘I feel an endless need to learn, to improve, to evolve, not only to please the coach and the fans, but also feel satisfied with myself’.

The second phase is to have no limitations. Restricting what you can achieve will limit what you can accomplish. Always keep in mind that there is always something new to learn, and that every experience you have will help you grow.

The ability to embrace setbacks/failure and learn from them, as well as what you need to do to better, is a critical component in developing a growth mindset. Above all, utilize that failure to drive your desire to succeed and reach your greatest potential. Because they have learned from their previous mistakes and failures, the most successful business people can perform successfully in any circumstances, both typical and tough.

Finally, identify your sources of inspiration that pushes you to develop and succeed. Your source of inspiration could be the ambition to become the best in your field.

Embracing a growth mindset, could be the answer to you reaching your full potential.

Growth Mindset vs Fixed Mindset: How what you think affects what you achieve

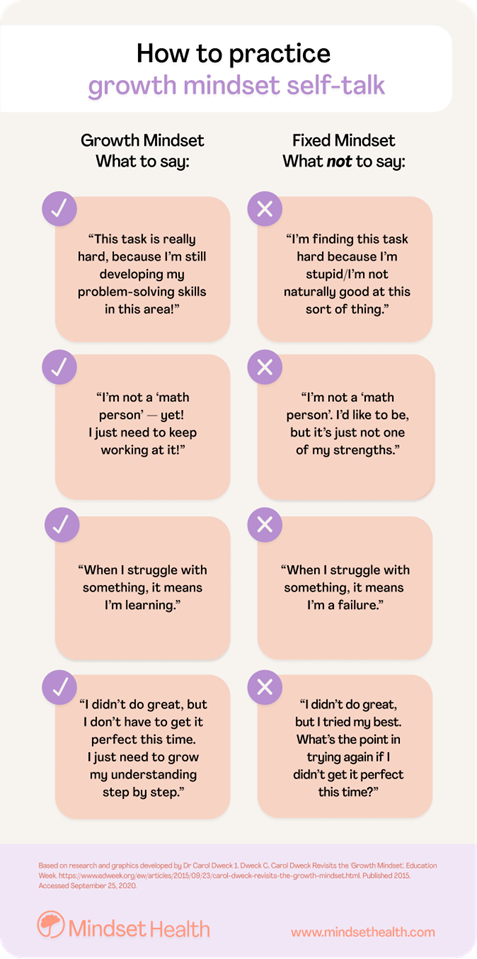

Can the way we think about ourselves and our skills impact our lives, whether we have a growth mindset or a fixed mindset? Absolutely. The way we think about our intellect and talents has an impact on not just how we feel, but also on what we achieve, whether we cling to new habits, and whether we continue to learn new skills.

If you have a growth mindset, you feel that your intelligence and abilities can be improved through time. If you have a fixed mindset, you believe that intelligence is fixed, therefore if you’re not excellent at something, you may believe that you’ll never be good at it.

Let’s look at growth vs. fixed mindsets together, explore the science, and see how people can change their mindsets over time.

Growth vs. fixed mindsets for life

The human brain was once thought to end developing in childhood, but we now know that it is always altering and changing. Many regions of the brain respond to events, and we can update our ‘software’ by learning.

Despite the scientific evidence, some individuals believe you are stuck with the abilities and ‘smarts’ you were born with. Carol Dweck, a Stanford University psychologist, was the first to investigate the concept of fixed and development mindsets.

Dr. Dweck characterized the two primary ways individuals think about intelligence or ability in her foundational work as being either:

• A fixed mindset: in this mindset, people believe that their intelligence is fixed and static.

• A growth mindset: in this mindset, people believe that intelligence and talents can be improved through effort and learning.

People who have a fixed mindset feel that their intelligence and abilities are predetermined. Fixed mindset people believe that “they have a specific amount (of knowledge) and that’s it,” according to Dr. Dweck, and that their goal is to “appear clever all the time and never look dumb.”

People with a growth mindset, on the other hand, recognize that not knowing or being good at anything is a transient state, so they don’t have to feel embarrassed or strive to prove they’re smarter than they are.

Dweck states that in a growth mindset, “students understand that their talents and abilities can be developed through effort, good teaching, and persistence.”

What is a growth mindset?

Intelligence and talent are seen as attributes that can be developed over time under a growth mentality.

This isn’t to say that people with a growth mindset believe they can become the next Einstein; there are still limits to what we can accomplish. People with a growth mindset believe that by putting up effort and taking action, they may increase their intelligence and talents.

A growth mindset also acknowledges that setbacks are an unavoidable part of the learning process, allowing people to ‘bounce back’ by boosting motivating effort.

A growth mindset views ‘failures’ as temporary and adaptable, making it essential for learning, resilience, motivation, and performance.

People that have a growth mindset are more likely to undertake the following:

• Be open to lifelong learning.

• Belief that intelligence may be enhanced

• Make a greater effort to learn

• Believe that hard work leads to mastery

• Believe that setbacks are just temporary.

• Consider criticism as a source of information.

• Takes on challenges with enthusiasm

• Take inspiration from others’ achievements.

• Look at feedback as an opportunity to improve.

What is a fixed mindset?

People with a fixed mindset believe that traits like talent and intelligence are fixed—that is, they believe they are born with the amount of intelligence and natural talents they will achieve as adults.

A fixed-minded individual avoids life’s obstacles, gives up easily, and is intimidated or threatened by other people’s success. This is due to the fact that a fixed mindset views intelligence and talent as something you “are,” rather than something you “grow.”

Negative thinking can be exacerbated by fixed mindsets. A person with a fixed mindset, for example, may fail at a task and assume it is because they aren’t smart enough to do it. A person with a growth mindset, on the other hand, can fail at the same task and assume it’s because they need to practice more.

Individual traits cannot change, no matter how hard you try, and people with a fixed mindset are more likely to:

• Believe intelligence and talent are static

• Avoid challenges to avoid failure

• Ignore feedback from others

• Feel threatened by the success of others

• Hide flaws so as not to be judged by others

• Believe putting in effort is worthless

• View feedback as personal criticism

• Give up easily

Who identified the growth mindset?

The growth mindset was originally presented by Stanford University psychologist Dr. Carol Dweck. Dweck’s ground-breaking research looked at why some people fail while others flourish.

High school pupils were given puzzles that ranged from easy to challenging in one research. Some students accepted failure and viewed it as a learning experience, much to the surprise of researchers, and this positive attitude was eventually termed by Dweck as the ‘growth mindset.’

Dweck’s research also discovered that, contrary to popular belief, it is more effective to praise the process rather than skill or innate qualities. Effort, strategies, perseverance, and resilience, in particular, should be praised. These procedures are crucial for providing constructive feedback and establishing a positive student-teacher connection.

While effort is an important aspect of a growth mindset, it shouldn’t be the primary focus of praise, according to Dweck in a 2015 paper. Effort should be viewed as a tool for learning and improvement. Continue telling yourself “excellent effort” after completing a task to promote a growth attitude, but also seek for ways to improve next time—so you feel good in the short and long term.

The benefits of a growth mindset

According to Dweck and others’ research, a growth mindset improves motivation and academic success.

One study looked at undergraduate students’ academic satisfaction after learning about the brain’s neuroplasticity.

Three one-hour seminars on brain functioning were used to encourage pupils to adopt a growth mindset. The participants in the control group were educated that there are several types of intelligence. After learning about the growth mindset, students demonstrated much stronger motivation and pleasure of science than students in the control group.

Teaching a growth mindset to junior high school pupils resulted in enhanced motivation and academic achievement, according to another study. A growth mindset was found to be especially useful for students studying science and mathematics, according to the researchers.

Students who advocated a growth mindset rather than a fixed mindset received superior grades in mathematics, languages, and grade point averages (GPA), according to studies.

A growth mentality also has the following advantages:

• Reduced burnout

• Fewer psychological problems, such as depression and anxiety

• Fewer behavioral problems

The neuroscience of a growth mindset

To better understand the neurological correlates of a growth mindset, scientists have examined electrical activity in the brain.

Researchers have discovered a correlation between a growth mindset and activation in two important areas of the brain using neuroimaging:

• The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC): involved in learning and control

• The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC): involved in error-monitoring and behavioral adaptation

Higher motivation and error correction appear to be linked to a growth mindset. It’s also linked to less activation in the face of negative input.

Furthermore, studies have discovered that when a person is told how they might develop — for example, recommendations on what to do better next time – the brain is most active in growth-minded people. Meanwhile, when a person with a fixed mindset is given information regarding their performance – such as the results of a test – the brain is engaged. This implies that persons with a growth mindset are more concerned with the process than with the outcome.

Only a few studies, however, have looked at the brain mechanisms that underpin diverse mindsets. More research is needed to determine the exact brain activity of those with development mindsets.

Can a person’s mindset change?

People can change their brain processes and thinking patterns in the same way that they can grow and expand their intellect.

Even as adults, the brain continues to develop and alter, according to neuroscience. The brain is comparable to plastic in that new neural pathways can be formed over time, allowing it to be remolded. As a result, scientists have coined the term “neuroplasticity” to describe the brain’s ability to change through growth and rearrangement.

According to research, the brain may form new connections, strengthen existing ones, and increase the speed with which pulses are transmitted. These findings imply that someone with a fixed mindset might gradually shift to a growth mindset.

You may shift from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset, according to Dr. Carol Dweck. Neuroscience studies demonstrating the malleability of self-attributes such as intelligence back this up.

There are a few techniques to cultivate a growth mindset.

Researchers discovered that teaching students about neuroscience research demonstrating that the brain is changeable and improves with effort can help them develop a growth mindset.

There are a variety of approaches to cultivating a development mindset, the most of which will be covered in the first course manual. Here are a few examples to get you started:

1. Recognize that you can improve scientifically.

Understanding that our brains are built to grow and learn is one of the most direct ways to foster a growth mindset. By exposing yourself to new experiences, you can build or strengthen neural connections in your brain, allowing you to’rewire’ your brain and become smarter.

2. Remove the inner voice that has a “fixed mindset.”

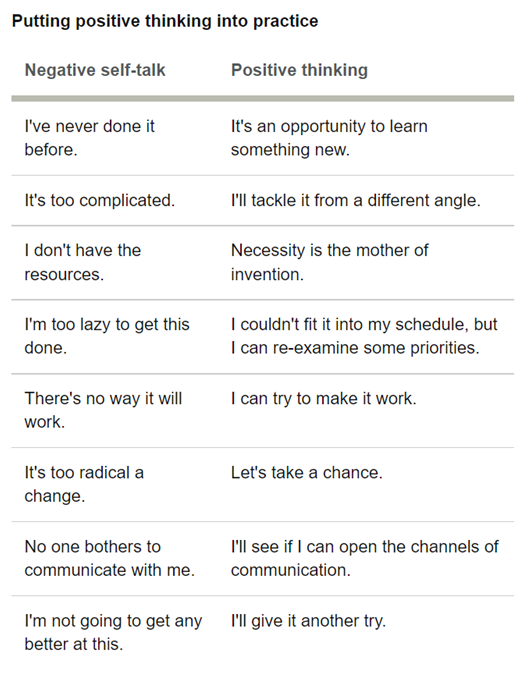

A negative inner voice exists in many people, and it works against a growth mindset. To cultivate a growth mindset, try flipping thoughts like “I can’t do this” to “I can do this if I keep practicing.”

3. The process should be rewarded.

Although society frequently honors people who achieve exceptional results, this might be counterproductive to a growth attitude. Rather, commend the process and the effort put forward. Dr. Carol Dweck’s research found that rewarding effort over outcomes boosted performance in a math game.

4. Gather feedback

Make an effort to get feedback on your work. Individuals are motivated to keep going when they are given progressive feedback on what they did well and where they can improve. Feedback is also linked to a happy dopamine response and aids in the development of a growth mindset.

5. Get out of your comfort zone

Having the courage to step outside of your comfort zone can aid in the development of a growth mentality. When faced with a challenge, select the more difficult alternative to allow you to progress.

Accept failure as part of the process

Failure, setbacks, and early perplexity are all part of the learning curve! Consider occasional ‘failures’ as valuable learning opportunities while trying something new, and try to enjoy the process of discovery along the way.

Final Thoughts

The growth mindset holds that intelligence and ability may be developed through hard work and learning. Setbacks are a crucial part of the learning process for growth-minded people, and they bounce back from ‘failure’ by putting in more effort. This mindset helps you to be more motivated while also helping you to reach your full potential. According to the limited data from neuroscience, those with a growth mindset have more active brains than those with a fixed mindset, especially in areas related to error correction and learning.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Growth Mindset

A growth mindset is a way of thinking about life and learning that prepares you to realize your full potential. Nothing about the human experience is fixed, according to research and wisdom ranging from Buddhist wisdom to cutting-edge neuroscience. This covers things like your personality, intelligence, and how you react to circumstances.

Formal schooling is at the heart of much of the study on the growth mindset. But it has a broad application, touching on the very core of life’s university, the everyday possibilities for learning and progress that are always present for those with the willingness and bravery to notice them.

This course manual will show you how to lay the groundwork, nourish the soil, and sow the seeds that will allow you to reach your maximum potential. A growth mindset is vital whether you want to become more self-aware, increase your productivity, ignite your success, love more, build your business, or enhance your abilities.

Carol Dweck: the growth mindset guru

Without mentioning Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, it’s impossible to describe the growth mindset. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, her groundbreaking book, gave a comprehensive explanation of it, based on a large body of scientific research and insights gained over two decades of effort.

Carol Dweck’s research is straightforward yet profound: one’s thinking determines a large part of one’s performance. Regardless of talent or skill, how you perceive your abilities has a significant impact on outcomes. You’re more likely to struggle if you believe you’re stupid and useless. However, if you begin to believe in your own potential and capability, the outcomes will follow.

According to Dweck’s research, your fundamental outlook on life may be altered. Because attitude affects so many parts of how you interact with the world, it has a significant impact on all facets of your life. The good news is that a growth mindset can be developed with a little work and a desire to improve.

Neuroplasticity: the neuroscience of the growth mindset

The physical structure of the brain reflects the concept of a growth mindset. Years ago, it was thought that the brain was permanently fixed. However, thanks to the development of neuroscience, this viewpoint has changed. The term “neuroplasticity” was coined in 1948 to describe how the brain constantly grows, alters, and adapts in response to new information.

“Neurons that fire together, wire together,” as the expression goes. Synapses are structures that allow neurons to communicate using electrochemical impulses. During the learning or repetition of a task, certain brain “pathways” are stimulated. These circuits in the brain strengthen with time, changing its structure.

From the moment you are born to the moment you die, your brain is always developing and evolving. Nothing about you is fixed, which serves as a great metaphor for the concept of growth. The potential of the brain to “alter in response to experience, repeated stimuli, environmental signals, and learning” is explained by experience-dependent neuroplasticity, for example.

Surprisingly, one study identified a neuroscientific link between the brain regions associated with growth mindset and intrinsic motivated behaviors. Author Betsy Ng explains, “Growth mindset is related to brain processes, and brain processes are related to motivated behaviors.” “By instilling a growth mindset, people will see the inherent worth of a task and self-regulate their behavior to complete it.”

The significance of a growth mindset in being the person you want to be

“Your personality isn’t permanent. The most successful people in the world base their identity and internal narrative on their future, not their past.” – Benjamin Hardy

A growth mindset, according to Carol Dweck, “can determine whether you become the person you want to be and whether you accomplish the things you value.” That’s a major deal, and it’s backed up by a lot of studies. It is a crucial foundation for all forms of self-development in my opinion.

Although Dweck’s work examines growth mindsets through the lens of success, she is quick to point out that there is no such thing as failure when you approach life as an opportunity to learn. This mindset sees every event as an opportunity to learn something new. This is one of the most liberating perspectives on life.

A word of caution: growth mindsets do not imply instantaneous change. Keep an eye out for small improvements over time, and be nice to yourself in the process. Human progress is cyclical, so don’t get discouraged if things don’t seem to be going your way.

There is a paradox of growth in that, in order to reach your full potential, you must accept where you are now and build from there. Trying to go away from who you are, or striving to improve in order to be more lovable, really stifles growth. Perfectionism is reduced, not enhanced, by cultivating the correct mindset.

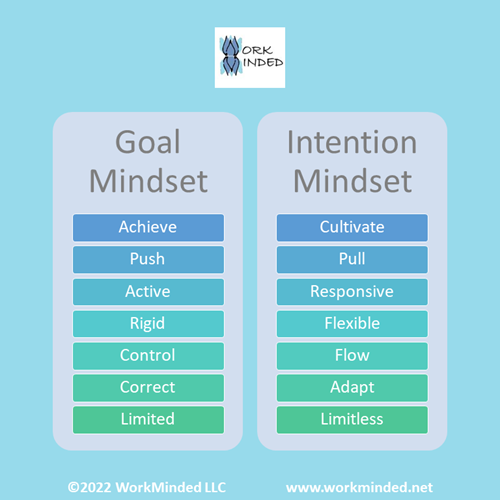

Chapter 2: Intention Sets the Course

“Everyone has busy, stress-filled, hectic lives; you barely have time to grab a cup of coffee in the morning, so you think there’s no way you have time to set a daily intention each morning, and that’s precisely why you need to,” says Melissa Maxx, a certified mindfulness coach. “If you don’t set an intention, you let the day determine your mood, rather than taking control and determining how you want the day to be.”

Simply said, an intention is a goal or purpose that you intend to accomplish – and paying more attention to your intentions can help you achieve incredible things in your life.

“Intention setting is empowering,” says Maxx. “Instead of feeling like a victim of circumstance, you become the conscious creators of your days and your life.”

Setting intentions has numerous advantages, but it’s not as simple as wishing on a star or concentrating on what you want. Here’s how to set your intentions the right way:

The Benefits of Setting Intentions

According to Jason Frishman, Psy.D., “intention setting” may sound woo-woo or like something you’d only do at the start of a yoga session, but it’s fundamental to anyone with objectives — aka most any human being. “As you learn and commit to your goals, intention becomes the very first step in achieving them.”

“Setting an intention is the initiation, the first step into your preferred story,” he says. “Particularly if your intention is solidly aligned with your values, then you have a powerful tool for moving forward and achieving your desires.” Regular statements of intention also allow you to change courses or adjust the path if needed, he says.

Intentions might be big (think: everlasting) or tiny (think: short-term; for the next day or even the next hour). In either case, they must be explicit and actionable, according to Frishman. (It’s similar to setting objectives using the “SMART” method.)

They may also be emotional, adds Sara Weand, L.P.C., licensed dialectical behavior therapy therapist and counselor. “Intentions involve the emotions you hope and intend to feel about a particular thing or situation in the future,” she says. “When you set an intention, it provides accountability and allows you to take control of your personal choices and life. It’s about being proactive in your own life, by purposely choosing how you want to live it.”

She claims that creating intentions allows you to actively live your life with meaning. You do this by becoming more present in both your personal life and your interpersonal relationships.

“When setting an intention, it’s like laying the foundation for what you’d like to have, feel, and experience versus just being a passive participant going through the motions,” she explains. “Intentions provide you with the opportunity to actively participate in your life the way you want to live it.”

So how, exactly, do you set intentions for the greatest chance at success? We will cover this in Course Manual 2.

What Is the Difference Between Intent and Impact, and Why Does It Matter?

Misunderstandings are unavoidable in everyday life. Whether it’s their approach to grocery shopping or how they handle dispute with a coworker, everyone has a unique perspective, lived experience, and set of biases that drive their actions.

People frequently try to justify their behavior by citing their motives, while others may have a quite different view of the overall consequence of their activities.

At best, this can result in a little misunderstanding. However, in rare circumstances, the gap between someone’s goal and the actual impact of their actions might result in considerable conflict.

While the distinction between intent and impact is frequently discussed in conflict resolution and trauma-informed care, it also comes up in everyday interactions and disputes.

Chapter 3: Three-part brain

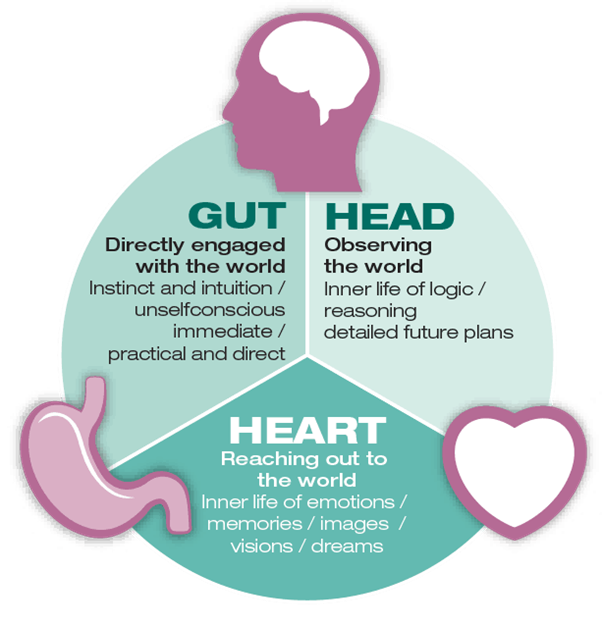

Did you realize you have three brains? That’s right, you read that correctly. You have three brains: one in your head, one in your heart, and one in your gut. The three brains are similar to an orchestra, with billions of neurons working together to create a harmonious symphony — harnessing an ever-changing network of neurons that function in unison.

Various actions within and across the huge communication networks are synchronized by oscillations induced by impulses from the three brains. The oscillations work together to guarantee that all components are able to perform their functions at the appropriate times, similar to how a conductor generates order among a vast number of instruments in an orchestra. Our three brains, on the other hand, stop working correctly when synchronization fails.

The Role of the Three Brains

Although the brains of the head, heart, and gut work together, they have distinct physical functions and perform distinct mental and emotional functions.

• Information is analyzed and logic is applied by the head brain.

• Emotions and feelings are how the heart brain senses the world.

• The gut brain is responsible for determining our identity and place in the world. The gut brain also teaches us self-preservation by educating us to trust our instincts — that “gut feeling” that we all have from time to time.

Source: www.naturalfactors.com

The Three Brains: Mind to Destiny

You were undoubtedly informed as a child that you only had one brain that controlled everything. You may have heard that the brain has two sides, one on the left and one on the right, as you grew older. Perhaps you learned about the Limbic System in early high school science class when discussing smells and memories. The ‘core’ three brains that make up the fundamental physiological processes of your mind will be discussed, as well as how they are connected to interpret events, guard you from threats, stressors, and generally catalog what experiences are good and bad for your overall survival.

Much of the information presented here originates from well-reviewed sources, particularly in the field of neuroscience. The majority of everything you’ll read below will be centered on the deliberate rebuilding of your brain in order to positively influence your life.

To frame your mentality, I recommend heading into this course manual with a question: How can you move from being a victim of circumstance and pre-conditioned behavior to being the creator of your own joy and success?

The Three Brains

The core infrastructure underpinning everything you think, feel, and believe is made up of three brains. Some of the functions in these three brains are within your immediate control, while others happen without your knowledge, sensation, or consent. The psychological order for what we’ll talk about more technically when we go deeper is:

Thinking – Doing – Being

This is a sequence of your being that has been at work in your life without you ever realizing it, and it has been constantly reinforced by the events that have either been placed in front of you or that you’ve sought out.

The technical names for each of these brains are:

• The Neocortex

• The Limbic or Mammalian Brain

• The Cerebellum is Reptilian Brain

In this course manual, we will discuss these regions of the brain and how each of the three sections affects how we establish a growth mindset.

Chapter 4: Basic Human Needs

Why do we behave the way we do? Why do we prize attention and status as indicators of success and value, but frown on complacency? What power is responsible for all of our feelings, activities, quality of life, and, eventually, our fates?

Did you know that understanding about human needs may explain all of the answers to these questions?

The inability to consistently address these essential demands is the root of all dysfunctional behaviors. People’s needs, on the other hand, aren’t just behind bad judgments – they’re also behind all of humanity’s great achievements. Understanding your own needs and psychology can help you not only avoid harmful behaviors and routines, but also achieve your objectives.

How do we develop our core needs?

Each of us is unique, shaped by our personal life experiences and emotions. Many of our fundamental desires emerge throughout childhood, when our minds are absorbing as much information as possible. This knowledge, whether good or bad, shapes our views and values, which in turn shape our entire universe. Stress has also been shown to have long-term consequences on brain chemistry and development in children.

Each of us prioritizes our needs differently, and our choices are influenced by the needs we prioritize first. While human wants are deep-seated, keep in mind that until you live there, your past is not your future. You can choose to meet your needs in a healthy way while also bringing balance to your life by honing your capacity to meet them all equally.

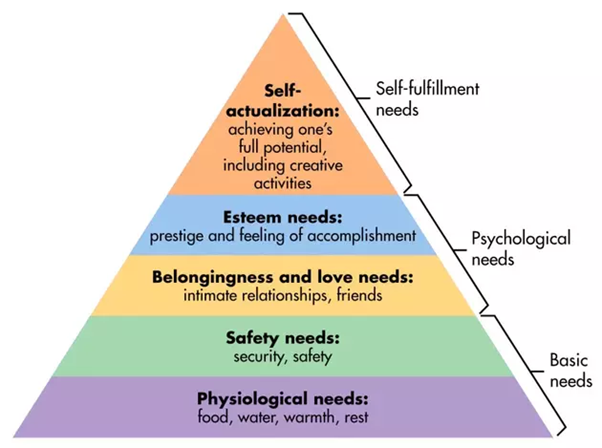

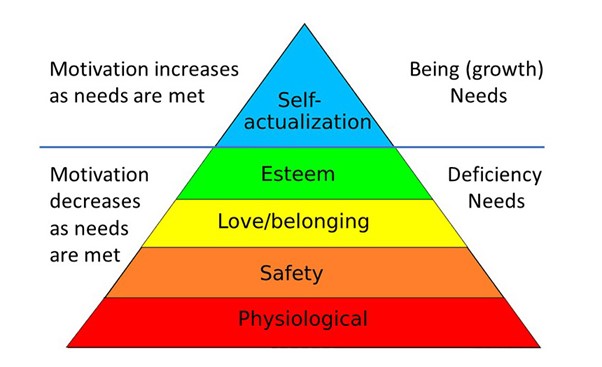

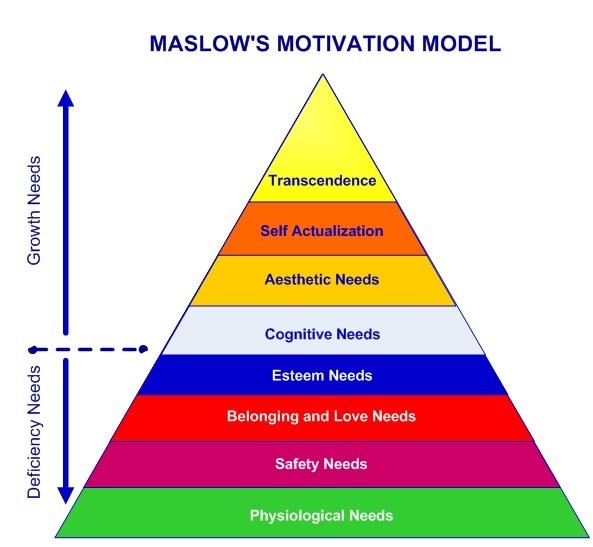

One of the most well-known theories of motivation is Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. According to Maslow’s hypothesis, our activities are driven by physiological requirements. It’s commonly depicted as a need pyramid, with the most fundamental demands at the bottom and more complex needs at the top.

What Is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs?

Abraham Maslow first introduced the concept of a hierarchy of needs in his 1943 paper titled “A Theory of Human Motivation,” and again in his subsequent book, Motivation and Personality. People are motivated to meet basic needs before moving on to more complex needs, according to this hierarchy.

While several existing schools of thought at the time, such as psychoanalysis and behaviorism, focused on undesirable behaviors, Maslow was more interested in discovering what makes individuals happy and what they do to reach that goal.

Maslow, a humanist, thought that people had an inborn need to be self-actualized, or to be the best version of themselves. However, in order to attain this ultimate goal, a number of more basic requirements must be met. Food, safety, love, and self-esteem are all necessities.

These needs, according to Maslow, are akin to instincts and play a significant role in motivating behavior.

There are five different levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which we will discuss in this course manual.

Chapter 5: Self-Esteem & Self-Efficacy

Everyone has a sense of self. Our experiences in life, as well as our judgments and assessments of ourselves, determine whether we have a positive or negative sense of self. There wouldn’t be anything to talk about if our self-evaluation was always correct. The issue is that our image of ourselves is frequently flawed.

This perspective can be skewed by previous experiences. For example, a person who grew up in a perfectionistic home may see herself as constantly falling short of the family’s standards. As a result, she sees herself as a failure, no matter how successful she is.

“How foolish!” or “What a dork!” could be spoken to a boy who is often picked on by his elder brothers. He might start to trust the labels he’s been given. People who believe in specific labels, unfortunately, typically live up to, or down to, those titles. The labels have the potential to produce a self-fulfilling expectation. He assumes he is foolish and never tries to prove differently.

What is self-concept?

The self-concept is a precise account of how you see yourself. This description may not be an exact representation of you if your perception is flawed, but it IS an accurate statement of what you believe about yourself.

Self-esteem and self-efficacy are the foundations of self-concept. A person’s self-concept may be tilted in the direction of a negative description if they have poor self-esteem. Some components of one’s self-concept may be entirely factual, such as “I have a college education” or “I don’t dance,” with no assessment of whether or not they are good or bad.

In fact, persons who have high self-esteem and self-efficacy are more likely to accept their limitations without feeling judged. “I don’t have a good sense of direction,” for example, might be simply stated without implying any positive or negative feelings.

What is self-esteem?

The admiration or respect a person has for himself or herself is known as self-esteem. Self-esteem is a term used to describe a person’s positive thoughts about themselves. However, self-esteem can refer to very specific areas as well as a general feeling about the self. For instance, a person may have low self-esteem regarding physical attractiveness and high self-esteem about ability to do a job well.

What is self-efficacy?

A person’s self-efficacy is their belief in their capacity to achieve a certain goal or task. It usually corresponds to an individual’s sense of competence. Competence varies depending on the situation. For example, a person may be extremely capable at competing in a specific sport but not of speaking in front of a group. As a result, total self-efficacy, which assesses an individual’s general sense of competence across a number of situations or tasks, may not be completely accurate.

Chapter 6: PERMA model of human flourishing

Humans have been striving for happiness since the beginning of time.

However, the term “happy” is notoriously difficult to define.

Happiness conjures up images of living the good life, flourishing, self-actualization, joy, and meaning. Is it possible to have any of these feelings in the midst of a chaotic world and bad circumstances? Can we learn to improve or develop talents that will help us achieve this “happy life”?

This course manual will outline the PERMA+ model and the theory of wellbeing, and provide practical ways to apply its components in your career or personal life.

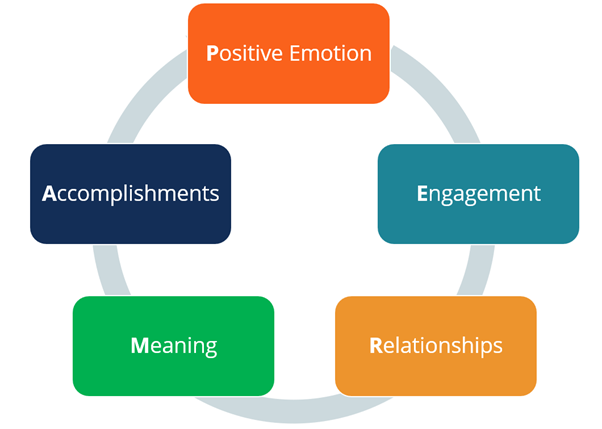

What Is Seligman’s PERMA+ Model?

With his criteria of a self-actualized individual, Abraham Maslow (1962) was one of the first in the area of psychology to characterize “wellbeing.” The PERMA model, which specifies the attributes of a flourishing individual, and Wellbeing Theory (WBT) are both foreshadowed by the concept of self-actualization.

In his inaugural address as the incoming president of the American Psychological Association in 1998, Dr. Martin Seligman shifted the focus away from mental illness and pathology and toward exploring what is good and beneficial in life. Positive psychology therapies that help make life worth living, as well as how to define, quantify, and generate wellbeing, have been the focus of theories and research since this period (Rusk & Waters, 2015).

In developing a theory to address this, Seligman (2012) selected five components that people pursue because they are intrinsically motivating and they contribute to wellbeing. These elements are pursued for their own sake and are defined and measured independently of each other (Seligman, 2012).

WBT differs from other theories of wellbeing in that the five components include both eudaimonic and hedonic components.

These five elements or components (PERMA; Seligman, 2012) are:

• Positive emotion

• Engagement

• Relationships

• Meaning

• Accomplishments

The PERMA model makes up WBT, where each dimension works in concert to give rise to a higher order construct that predicts the flourishing of groups, communities, organizations, and nations (Forgeard, Jayawickreme, Kern, & Seligman, 2011).

Each of the PERMA components has been proven to have strong positive connections with physical health, energy, job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and organizational commitment in studies (Kern, Waters, Alder, & White, 2014).

In addition, PERMA is a better predictor of psychological distress than earlier distress ratings (Forgeard et al., 2011). This suggests that proactively addressing the PERMA components improves aspects of wellbeing while also reducing psychological suffering.

Chapter 7: Illness/Wellness Continuum

Understanding the illness wellness continuum

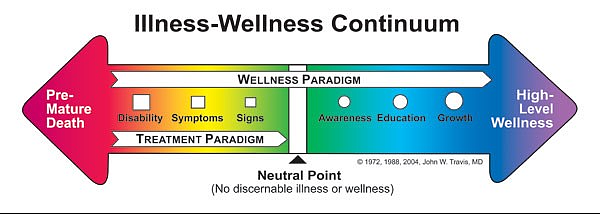

Wellness is more than just the absence of illness. It’s critical to understand how to achieve optimum wellbeing in order to live your best life.

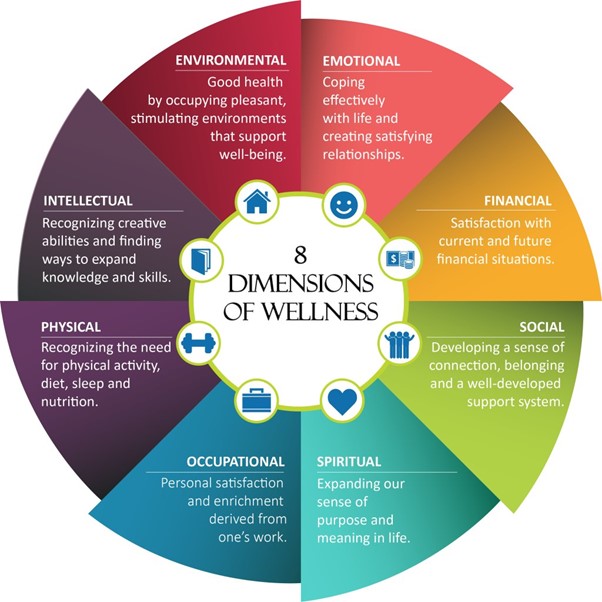

The National Wellness Institute’s Illness-Wellness Continuum posits that wellbeing is more than just whether or not you have symptoms of an illness. It refers to one’s mental, emotional, and physical well-being.

We frequently associate health with visible conditions such as disease, injuries, or disability. But what about anxiety and despair, as well as other hidden aspects of our lives that affect our general health and well-being?

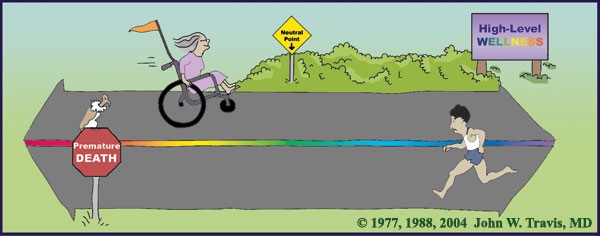

This continuum is a sliding scale on which we are continually shifting. On the right, you’ll find optimum health and wellbeing, while on the left, you’ll find illness and death. One can keep moving towards the positive end of the spectrum by increasing awareness, education, and growth.

Dimensions of wellness

You may notice fewer or more dimensions depending on where you look. According to the National Wellness Institute, there are six dimensions:

1. Emotional Wellness? – the awareness and acceptance of your feelings and emotions and how you cope with relationships and life in general.

2. Occupational Wellness – the idea of enriching your life through work that aligns with your values and is fulfilling and rewarding.

3. Physical Wellness – how you care for yourself through what you eat and drink, ensuring you are sleeping enough, and exercising.

4. Social Wellness – how you contribute to your community and interact with others.

5. Intellectual Wellness – keeping your brain stimulated by engaging in challenging and creative activities.

6. Spiritual Wellness – to discover your meaning of life and using your beliefs and values to live a life with purpose.

Stages on the wellness continuum

The ultimate goal as you progress along the spectrum is to improve your mental, bodily, and spiritual well-being so that you can reach your maximum potential.

A neutral zone separates the stages on this journey. As you go toward sickness, you will encounter signs, symptoms, and impairment. You pass through awareness, education, and progress on your route to high-level wellness.

Throughout your life, and even day to day, you can travel up and down this spectrum.

How does it work

You should practice behaviors that assist you advance along the positive road in your daily life.

You must be in a good frame of mind to live your life to its utmost potential. The body cannot perform at its optimum if it is in a state of physical or emotional illness.

As you work toward wellness, many aspects of your life can improve, including your physical health and relationships.

Newton’s First Law of Motion, which states that a body in motion stays in motion, is presumably familiar to you. The same is true when it comes to achieving wellness. When one aspect of your life improves, it inspires you to make other positive adjustments that benefit your entire health.

how can you apply it to your everyday life

You can make your way along the wellness continuum by taking a series of small steps. The following are simple things you may gradually incorporate into your life to aid with each aspect of wellness:

• Eating well by adding in wholesome nutritious food to your diet.

• Get your body moving every day.

• Practice meditating.

• Try activities that challenge you and make you step out of your comfort zone.

• Do caring acts for others.

• Practice mindfulness.

• Make sure your circle is filled with people who contribute positively to your life.

• If you belong to a church, participate in activities.

• Rest well! Shoot for at least 7-8 hours of sleep every night.

• Try to limit how often you are on social media.

• Pick up a new hobby.

Common questions

What are the five health stages that form the wellness continuum?

The 5 stages along the continuum are disability, symptoms, awareness, education, and growth.

What are the two categories that make up the wellness continuum?

Premature mortality is at the extreme of the illness spectrum, and high level wellness is at the end of the wellness spectrum.

What are the six dimensions of wellness?

Emotional Wellness, Occupational Wellness, Physical Wellness, Social Wellness, Intellectual Wellness, and Spiritual Wellness are the 6 dimensions.

Is there such a thing as a health-illness continuum?

The health illness, illness-wellness, and health continuum are all terms used to describe the wellness continuum. All of these words are used to describe the same thing.

Chapter 8: Positivity-Focused

Positive thinking: Stop negative self-talk to reduce stress

Positive thinking helps with stress management and can even improve your health.

Do you see your glass as half-full or half-empty? How you respond to this age-old question about positive thinking may reflect your outlook on life, your attitude toward yourself, and whether you’re optimistic or pessimistic — and it could even have an impact on your health.

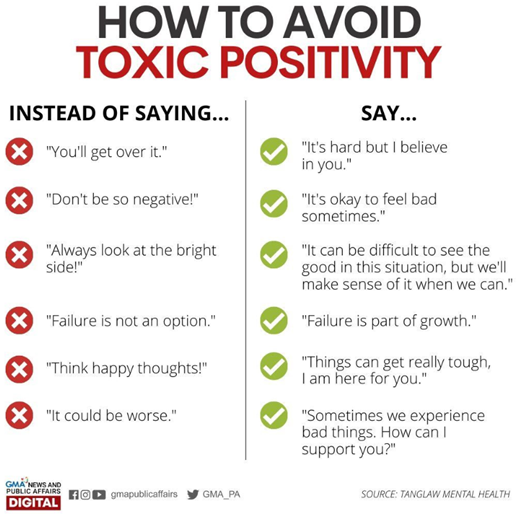

Indeed, some research suggests that personality qualities like optimism and pessimism might have an impact on a variety of aspects of your health and well-being. Positive thinking, which is often associated with optimism, is an important component of good stress management. And effective stress management is linked to a slew of health advantages. Don’t worry if you’re a pessimist; positive thinking abilities may be learned.

Understanding positive thinking and self-talk

Positive thinking does not imply that you disregard the unpleasant aspects of life. Positive thinking simply means approaching unpleasant situations in a more positive and productive manner. You expect the best, not the worst, to happen.

Self-talk is a common starting point for positive thinking. The unending stream of unsaid thoughts that go through your head is known as self-talk. These thoughts might be either pleasant or negative. Logic and reason play a role in some of your self-talk. Other self-talk may stem from misunderstandings you acquire as a result of a lack of facts or expectations based on previous notions about what might happen.

If the majority of your thoughts are negative, you are more likely to have a pessimistic attitude on life. If you think largely positively, you’re probably an optimist, or someone who believes in positive thinking.

The health benefits of positive thinking

The impacts of positive thinking and optimism on health are still being studied by researchers. Positive thinking may provide the following health benefits:

• Increased life span

• Lower rates of depression

• Lower levels of distress and pain

• Greater resistance to illnesses

• Better psychological and physical well-being

• Better cardiovascular health and reduced risk of death from cardiovascular disease and stroke

• Reduced risk of death from cancer

• Reduced risk of death from respiratory conditions

• Reduced risk of death from infections

• Better coping skills during hardships and times of stress

It’s unclear why those who practice positive thinking have such good health. According to one theory, having a positive mindset helps you cope better with stressful events, reducing the negative health impacts of stress on your body.

Positive and optimistic people are also regarded to have healthier lifestyles, as they engage in more physical exercise, eat a healthier diet, and don’t smoke or drink excessively.

Chapter 9: Strengths-Based

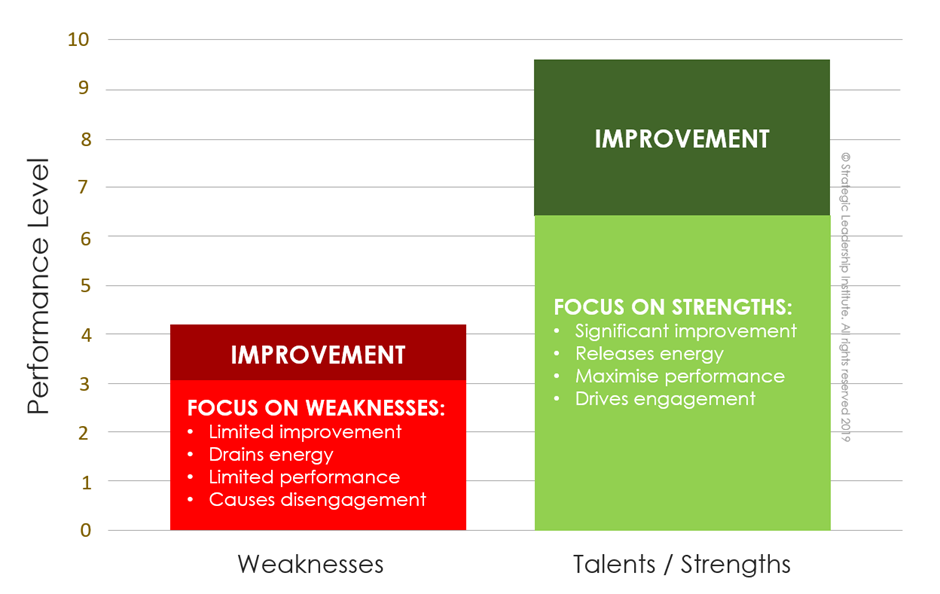

The strengths-based approach is both a complement and a counterbalance to the deficit-based approach. And strengths-based development allows us to spend more time developing and stretching our strengths rather than hammering out our flaws and deficiencies.

What is strengths-based development and how does it vary from deficit development?

We have been swimming in a sea of negativity since birth. We are surrounded with guidance and diktats on how we should and shouldn’t behave from the moment we are born, based on others’ deeply held convictions about what is wrong and what is right.

We are also neurologically predisposed to focus on risk and danger considerably more than on pleasant stimuli, according to research. This combination creates the ideal environment for a negative internal conversation to emerge from a young age. This ‘inner critic,’ which we all have, will tell us that we need to improve, that we need to be stronger, faster, smarter, more, and different. Finally, our inner critic tells us that we are inadequate, that we aren’t good enough.

And because we’re so focused on avoiding the bad stuff, working on it, improving it, or running away or hiding from it, when we come across something positive in ourselves – a quality, skill, trait, or talent, something that we naturally find easy or that we’re good at – we often don’t notice it at all. As a result, we overlook the positive or downplay its significance. Our inner critic is continuously reminding us to concentrate on the far more significant issue of what isn’t good enough.

As a result, most of us greatly underbake the opportunity to focus on what we’re naturally good at – our strengths – to turn them from good to outstanding, to advance from competence to mastery, at school, at home, and at work. All because of the natural human negativity bias, which is exacerbated by negative external feedback. Bring on the strengths-based strategy, especially strengths-based development.

All elements of our lives — school, home, and work – resonate with strengths-based development. It signals a shift back to focusing on the good and improving in areas where we are naturally strong. This course manual will concentrate on strengths-based development, why it is important, and how we may devote more of our time to it.

Growth mindset’s critical significance in strengths-based development

If you have a growth mindset, you’re more likely to appreciate difficulties, despite the danger, because you value learning and growth more than any fears you might have about people thinking you’re incompetent. And, because you’re eager to try new things, you frequently don’t know what you’re doing, at least at first, but you don’t see this as a danger; rather, you see it as an opportunity to learn and improve at something you could appreciate.

Any fixed mindset worries and anxieties might be amplified with strengths-based learning and development since you’re moving into a space where you’re owning that you have strengths and that you’re choosing to work on them in order to become even better in those areas. The inner critic voices of fixed mindsetters may now be saying things like, ‘well, you’re setting yourself up to fail here, aren’t you?’, ‘you don’t want to come across as bigheaded or arrogant by declaring you’ve got all these strengths, do you?’, and so on.

As a result, you should be aware that working on enhancing and expanding your talents can cause discomfort and worry before things return to normal. Stick with the discomfort since it’s where you’ll learn the most and have the most fun.

Chapter 10: Cognitive Biases

What Is Cognitive Bias?

Have you ever been so engrossed in your phone conversation that you miss the fact that the light has gone green and it is your turn to cross the street?

Have you ever exclaimed, “I knew it was going to happen!” after your favorite baseball team loses after blowing a big lead in the ninth inning?

Have you ever found yourself just reading news reports that bolster your own point of view?

These are only a handful of the many examples of cognitive bias that we encounter on a daily basis. But, before we get into these various biases, let’s take a step back and clarify what bias is.

A cognitive bias is a mental error that causes you to misinterpret information from the environment, affecting the logic and correctness of your decisions and judgments. Biases are unconscious, automatic processes that speed up and improve the efficiency of decision-making. Heuristics (mental shortcuts), societal pressures, and emotions, for example, can all contribute to cognitive biases.

Bias is a tendency to favor or oppose a person, group, concept, or item, usually in an unjust way. Biases are natural — they’re a part of our makeup — and they don’t only live in our heads; they have an impact on how we make decisions and act.

Biases are divided into two categories in psychology: conscious and unconscious biases. You are aware of your attitudes and the behaviors that emerge from them when you have conscious bias, also known as explicit bias.

Explicit bias can be beneficial since it gives you a feeling of self and helps you make smart judgments (for example, being biased towards healthy foods).

However, when these biases manifest themselves as conscious stereotyping, they can be extremely hazardous.

Unconscious bias, also known as cognitive bias, refers to a set of unintentional biases in which you are unaware of your attitudes and the behaviors that emerge from them.

We get around 11 million bits of information each second, but we can only analyze about 40 bits per second, thus cognitive bias is often the product of your brain’s attempt to simplify information processing.

As a result, we frequently rely on mental shortcuts (also known as heuristics) to help us make sense of the world quickly. As a result, these errors are frequently caused by issues with thinking, such as memory, attention, and other mental errors.

Unconscious biases, like conscious prejudices, can be useful because they don’t involve much mental effort and allow you to make decisions fast. However, much like conscious biases, unconscious biases can also be destructive prejudice that harms an individual or a group.

And, while it may appear that unconscious bias has recently increased, particularly in the context of police violence and the Black Lives Matter movement, this is not a new phenomena.

The History of Cognitive Bias: A Crash Course

Israeli psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman created the term “cognitive bias” in the 1970s to explain people’s erroneous habits of thinking in response to judgment and decision issues.

The heuristics and biases study program of Tversky and Kahneman looked into how people make decisions with limited resources (for example, limited time to decide which food to eat or limited information to decide which house to buy).

People are compelled to rely on heuristics, or rapid mental shortcuts, to help them make judgments as a result of their limited resources.

Tversky and Kahneman sought to know more about the unique biases that come with this type of assessment and decision-making.

To do so, the two researchers used a research paradigm in which participants were given with a reasoning issue with a computed normative response (they used probability theory and statistics to compute the expected answer).

The actual responses of the participants were then compared to the prepared solution to uncover the consistent mental aberrations.

The researchers were able to detect several norm breaches that occur when our minds rely on these cognitive biases to make decisions and judgements after conducting several tests involving a large number of reasoning issues.

Chapter 11: Limiting Beliefs

If you go back to your earliest childhood recollections, you’re sure to recall times when you were fearless, when your curiosity led you to places you’d never dare to go now.

As you grew older, though, you were bombarded with a never-ending litany of rules about what you should say, how you should act, and what you should do. As a result, you’ve probably developed limiting beliefs and may not have reached your full potential.

While you must follow some standards, it is critical that you do not limit yourself from living a complete life.

This course manual will show you how to recognize and overcome your limiting beliefs.

What Are Limiting Beliefs?

Have you ever said something to the effect of “I’m not good at arithmetic” or “I have two left feet and could never be a decent dancer”? These are examples of limiting beliefs that trap you in a box you created for yourself and often define you incorrectly.

A limiting belief is a state of mind, conviction, or belief that you hold to be true and that you believe to be true, but that confines you in some way. This limiting idea could be about yourself, your interactions with others, or the world and how it functions.

Limiting beliefs can have a variety of harmful consequences. They may prevent you from making good decisions, taking new chances, or realizing your full potential. Limiting beliefs can keep you caught in a negative mindset and prevent you from enjoying the life you really want.

Causes of Limiting Beliefs

Do you know what generates limiting beliefs now that you know what they are? What are their origins, and how have they influenced your life choices?

Some claim that individuals aren’t wired to be open-minded since our biases lead us to seek out only good and agreeable information.

Aside from inherent biases and an incapacity to be open-minded, there are other factors that contribute to restricting views. You’ll find a handful that may strike a chord with you below.

Family Beliefs

Your parents most certainly tried to instill principles and ideals in you as a child. These were frequently based on their own family’s views and ideals about how you and the world should be. It could be things like choosing a job route, how to act, and how to interact with others.

Based on the views they established in you, you may develop your own limiting beliefs. Your parents, for example, may instill in you the attitude that authority should never be questioned.

As a result, you may assume that unjust treatment from persons in positions of authority must be accepted rather than contested. It’s possible that you won’t be able to notice this conduct.

Education

Education also has a significant impact in the formation of limiting beliefs. Whether you learn from your parents, school, or friends, they all have an influence on what you believe to be true. This is due to the fact that they are both in positions of power and are constantly exchanging information, ideas, and views about how the world works.

When you’re learning from someone you respect, you’re more likely to believe what they’re telling you is true.

Experiences

It is typical for people to draw conclusions after making decisions or having life experiences. If you fell in love and it ends in heartbreak, for example, you might assume that love is always painful.

Negative events, in particular, can have a significant impact on your limiting beliefs. It’s critical to remember that the conclusions you reach following terrible situations are only relevant for a limited time.

Chapter 12: Leadership: Process Feedback

The Importance of Feedback

Any leader’s skill set must include the ability to give and receive feedback. This is a talent that project managers, team leaders, teachers, and coaches develop over the course of their careers. It is critical to not only give but also receive feedback in order to effectively share knowledge within teams and organizations. Let’s take a closer look at its worth and see how we can improve our ability to deliver it.

Constructive feedback is a powerful tool for fostering a positive work atmosphere, increasing productivity and engagement, and improving performance. It has a favorable impact on communication, team member engagement, and teamwork outcomes in a variety of industries. This is how it works for various processes:

• The importance of feedback in the workplace is hard to overestimate: sharing information on what can and needs to be improved helps optimize the work process and get things done in less time.

• Feedback is extremely beneficial to leadership and communication because it clarifies the image and enhances transparency.

• Feedback is critical in education and learning since it aids in the faster adoption of new information and the avoidance of common errors.

• The same can be said for feedback in sports and coaching: it aids in the development of new skills and the attainment of improved results.

Constructive criticism in the workplace is critical: for a company to succeed and thrive, it must have effective communication. Feedback not only boosts employee morale, but it also teaches us more about ourselves, our strengths and shortcomings, our behaviors, and how our actions effect others. It also improves our self-awareness and promotes personal growth.

It is not always necessary for feedback to be positive. Negative criticism identifies areas where we need to improve, allowing us to improve our job in the long term. However, it is critical that you provide feedback in a skillful and productive manner; otherwise, there would be no basis for progress.

It goes without saying that providing good, constructive feedback is challenging, so I’ll explain how to do it and what the key advantages are. This course manual will also provide you with some examples of constructive feedback words to utilize at work.

Curriculum

Cultivating Potential – Workshop 2 – Growth Foundation

- Growth Mindset

- Intention Sets the Course

- Three-Part Brain

- Basic Human Needs

- Self-Esteem & Self-Efficacy

- PERMA Model of Human Flourishing

- Illness/Wellness Continuum

- Positivity-Focused

- Strengths-Based

- Cognitive Biases

- Limiting Beliefs

- Leadership: Process Feedback

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Cultivating Potential corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student