Global Supply Chain – Workshop 12 (Strategy Execution)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Global Supply Chain is provided by Mr. Buck BS Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Mr Buck is a Certified Learning Provider (CLP) at Appleton Greene and he has experience in management, production and globalization. He has achieved a Bachelor of Applied Science IET/MET in Concentration in Operations Management. He has industry experience within the following sectors: Biotechnology; Manufacturing; Aerospace; Logistics and Technology. He has had commercial experience within the following countries: China; United Kingdom; Ireland and United States of America, or more specifically within the following cities: Shanghai; London; Cork; Minneapolis MN and Chicago IL. His personal achievements include: founded a corporation in 1991 and sold it in 2018 for $400m; entrepreneur of the year Ernst & Young 1998; entrepreneur of the year Ernst & Young 2004; built global manufacturing infrastructure and lead acquisition of 16 companies. His service skills incorporate: strategic planning; leadership development; supply chain; executive mentoring and merger & acquisition.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

The execution of an organization’s supply chain strategy is best managed as part of the Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) process and meetings. In case an organization should not have an S&OP process, this may be a good time to develop and implement one as part of their integrated supply chain strategy.

Objectives

01. Responsibility Awareness: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Team Alignment: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Assess Capabilities: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. KPI’s: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Decision Acceptance: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Strategy Flow: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Employee Engagement: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Transformation Program: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Leadership Roles: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Scorecards: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Inclusive Planning: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Middle Management: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Responsibility Awareness: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Team Alignment: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Assess Capabilities: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. KPI’s: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Decision Acceptance: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

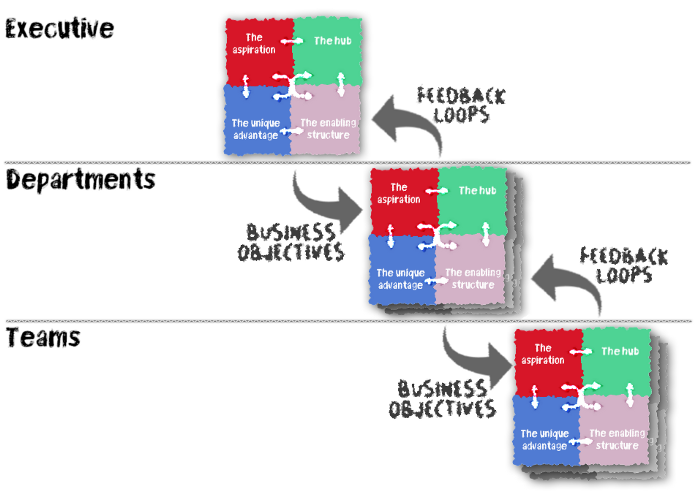

06. Strategy Flow: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Employee Engagement: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Transformation Program: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Leadership Roles: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Scorecards: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Inclusive Planning: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Middle Management: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Responsibility Awareness.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Team Alignment.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Assess Capabilities.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze KPI’s.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Decision Acceptance.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Strategy Flow.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Employee Engagement.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Transformation Program.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Leadership Roles.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Scorecards.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Inclusive Planning.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Middle Management.

Introduction

The Keys to Executing a Successful Strategy

In the Global Supply Chain, only solid execution can keep you on the competitive map after a brilliant strategy, blockbuster product, or breakthrough technology has put you there. You must be able to follow through on your promises. Unfortunately, the majority of businesses, by their own admission, aren’t particularly good at it.

Execution is the product of thousands of decisions made every day by personnel acting in their own self-interest and based on the knowledge they have. We’ve identified four essential building blocks executives may use to impact those behaviors : clarifying decision rights, creating information flows, aligning motivators, and implementing structural adjustments. (We’ll refer to them as choice rights, information, motivators, and structure for the purpose of simplicity.)

Most supply chains’ first turn to structural measures to improve performance since changing lines across the org chart appears to be the most obvious option because the changes are visible and tangible. These actions usually produce some short-term efficiency fast, but they simply address the symptoms of dysfunction rather than the core reasons. Companies frequently finish up back where they started after several years. Structural change can and should be a component of the path to better execution, but it’s better to think of it as the apex of any organizational transformation rather than the cornerstone. In fact, our research reveals that activities related to decision rights and information are significantly more important than improvements to the other two building blocks, and are roughly twice as effective. (See the exhibit “Strategy Execution’s Most Important Factors.”)

What Is Most Important in Supply Chain Strategy Execution?

When a corporation fails to carry out its strategy, the first thought that comes to mind is to reorganize.

Case Study

Consider the situation of a multinational consumer packaged products corporation that went through a major reorganization in the early 1990s. (In this and subsequent situations, we have changed identifying details.) Senior management, dissatisfied with the company’s performance, did what most firms did at the time: They reorganized. They reduced the number of layers of management and expanded the scope of control. The cost of management personnel dropped by 18% in a short period of time. However, eight years later, it was deja vu all over again. The layers had crept back in, and control swaths had shrunk once more. Management had addressed the outward symptoms of bad performance but not the underlying cause—how people made decisions and were held accountable—by focusing solely on structure.

This time, management focused on the mechanics of how work was completed rather than lines and boxes. Rather than looking for methods to decrease expenses, they concentrated on improving execution—and in the process, they found the actual causes of the performance gap. Managers lacked a clear understanding of their duties and responsibilities. They didn’t know which decisions were theirs to make naturally. Furthermore, there was a shaky link between performance and pay. This was a firm that valued micromanagement and second-guessing over accountability. Middle managers spent 40% of their time justifying and reporting upward, or challenging their direct reports’ tactical decisions.

With this knowledge, the organization created a new management model that defined who was responsible for what and established a link between performance and compensation. For example, it was common practice at this organization, and not uncommon in the sector, to promote employees fast, within 18 months to two years, before they had a chance to see their ideas through. As a result, even after being promoted, managers at all levels continued to do their old tasks, gazing over the shoulders of their direct reports who were now in control of their projects and, all too frequently, taking over. People are staying in their jobs longer these days so they may follow through on their own ideas, and they’re still around when the benefits of their labors begin to show. Furthermore, the outcomes of such projects continue to factor into their performance appraisals for some time after they’ve been promoted, compelling managers to live up to the standards they set in earlier employment. As a result, forecasting has improved in accuracy and consistency. The improvements did result in a structure with fewer layers and broader control spans, however this was a side effect rather than the primary goal of the alterations.

The Components of Effective Execution

Our judgments are the result of decades of hands-on experience and extensive investigation. What are the most effective techniques of reorganizing, motivating, improving information flows, and clarifying decision rights? We began by creating a list of 17 traits, each of which corresponded to one or more of the four building blocks we knew were necessary for effective execution—traits such as the free flow of information across Global Supply Chain organizational boundaries or the degree to which senior leaders refrain from intervening in operational decisions.

Organizational Effectiveness: The Fundamental Characteristics

The importance of decision rights and knowledge to good plan implementation is shown by ranking the attributes. The first eight characteristics correspond to decision-making authority and information. Only three of the 17 qualities have anything to do with structure, and none of them are ranked higher than thirteenth. Here, we’ll go over the top five characteristics.

Everyone Is Aware Of The Decisions And Acts For Which They Are Accountable

In companies that excel at execution, 71 percent of employees agree with this statement; in companies that struggle with execution, only 32 percent agree. As a corporation grows older, decision powers begin to blur. Young companies are often too focused on getting things done to take the time to properly define roles and duties from the outset. Why should they, after all? It’s not difficult to find out what other people are up to in a small organization. So things go well enough for a while. Executives come and go as the company grows, bringing with them and taking away various expectations, and the approval process becomes more confusing and muddy with time. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to tell where one person’s responsibility ends and another’s begins.

This was discovered the hard way by one major consumer-durables corporation. It was difficult to identify anyone below the CEO who felt truly accountable for profitability since there were so many people making competing and contradicting judgments. The corporation was divided into 16 product divisions, which were then divided into three geographic groups: North America, Europe, and the rest of the world. Each division was responsible for meeting specific performance goals, although functional employees at corporate headquarters were in charge of spending goals, such as how R&D dollars were allocated. Divisional and geographic leaders’ decisions were frequently overruled by functional leaders. As the divisions hired more people to help them build airtight arguments to challenge corporate decisions, overhead expenses began to rise.

While divisions argued with functions, each layer weighed in with queries, decisions stagnated. Because functional leaders were responsible for awards and promotions, functional staffers in the divisions (for example, financial analysts) generally deferred to their higher-ups in corporate rather than their division vice president. The CEO and his executive staff were the only ones who have the authority to settle disagreements. All of these symptoms compounded and delayed execution—until a new CEO was brought in.

What is the Definition of Global Supply Chain Strategy?

For one thing, it’s not operational efficiency.

By reorganizing the divisions to focus on customers, the new CEO elected to focus less on cost control and more on profitable growth. As part of the new organizational architecture, the CEO clearly delegated profit responsibility to the divisions, as well as the power to rely on functional operations to achieve their objectives (as well as more control of the budget). Corporate functional responsibilities and decision rights were recast to better serve the divisions’ demands as well as to construct the cross-divisional connections needed to improve the business’s overall global capabilities. The functional leaders, for the most part, were aware of market realities, which necessitated some changes to the business’s operating model. It helped that the CEO included them in the organizational redesign process, so the new model wasn’t something they were forced to adopt, but rather something they collaborated on.

Critical Information Regarding The Competitive Landscape Is Rapidly Communicated To Headquarters

In strong-execution firms, 77 percent of employees agree with this statement, whereas just 45 percent of employees in weak-execution businesses do.

Headquarters can play a critical role in spotting patterns and disseminating best practices across company sectors and geographical regions. However, it can only play this coordinating role if it has current and accurate market intelligence. Otherwise, rather than deferring to operations that are much closer to the client, it will tend to push its own agenda and policies.

Case Study

Consider The Case Of Caterpillar, A Heavy-Equipment Company

Caterpillar’s organization was so terribly mismatched a generation ago that its very existence was threatened. Today, it is a highly successful $45 billion worldwide firm, but it was so horribly misaligned a generation ago that its very survival was threatened. Decision rights were hoarded at the top by functional general offices in Peoria, Illinois, despite the fact that much of the information needed to make such decisions was in the hands of sales managers in the field. “It just took a long time to get decisions going up and down the functional silos, and they really weren’t good business decisions; they were more functional decisions,” One field executive remarked. The information that did make it to the top had been “whitewashed and varnished numerous times over along the way,” according to current CEO Jim Owens, who was then a managing director in Indonesia. Because they were cut off from knowledge about the external market, senior executives concentrated on the organization’s internal operations, overanalyzing issues and second-guessing lower-level judgments, costing the company opportunities in fast-moving markets.

Concerning The Information

Organizational efficiency was tested by asking respondents to complete a 19-question online diagnostic.

Pricing, for example, was based on cost and established by the pricing general office in Peoria rather than market realities. Salespeople all across the world were losing sale after sale to Komatsu, whose competitive pricing routinely outperformed Caterpillar’s. The company suffered its first yearly loss in its nearly 60-year history in 1982. It lost $1 million each day, seven days a week, in 1983 and 1984. Caterpillar had lost a billion dollars by the end of 1984. By 1988, then-CEO George Schaefer was in charge of a bureaucracy that was “giving me what I wanted to hear, not what I needed to know,” as he put it. As a result, he formed a task force of “renegade” middle managers to design Caterpillar’s destiny.

Ironically, the best method to ensure that the correct information reached headquarters was to ensure that the correct decisions were made far further down the chain of command. Top executives were freed to focus on more global strategic challenges by delegating operational responsibilities to those closer to the action. As a result, the corporation was divided into business divisions, each with its own P&L statement. Overnight, the all-powerful general offices that had previously existed ceased to exist. Their engineering, pricing, and manufacturing expertise was divided among the new business units, which could now design their own products, devise their own manufacturing procedures and schedules, and determine their own prices. The shift radically decentralized decision-making authority, handing market decisions to the units. Return on assets became the universal metric of success, and business unit P&Ls were now monitored similarly across the firm. Instead of using obsolete sales data to make inefficient, tactical marketing judgments, senior decision makers at headquarters may make wise strategic choices and trade-offs with this accurate, up-to-date, and directly comparable information. The new model was implemented in the company within 18 months. “It was a fantastic metamorphosis of a kind of slow firm into one that genuinely has entrepreneurial zeal,” Owens says. And that change happened quickly because it was decisive and comprehensive; it was thorough; it was universal, global, and all at once.”

Decisions Are Rarely Questioned After They Have Been Made

Whether or whether someone is second-guessing you is a matter of perspective. Managers further up the supply chain may not be delivering incremental value; instead, they may be slowing progress by redoing their subordinates’ work while effectively shirking their own. In this study, 71 percent of respondents in poor-execution firms believed their judgments were being second-guessed, compared to only 45 percent of respondents in strong-execution companies.

Case Study

Consider the case of a global humanitarian organization dedicated to poverty alleviation. It had a situation that others may envy: it was under stress as a result of increased donations and a corresponding increase in the depth and breadth of its program offerings. As you might anticipate, this nonprofit was filled with mission-driven individuals who took a strong personal interest in their work. Delegation of even the most routine administrative responsibilities was not rewarded. Copier repairs, for example, would be individually overseen by country-level supervisors. As the company grew, managers’ failure to delegate resulted in decision paralysis and a lack of accountability. It was an art form to second-guess someone. When there was a question about who had the authority to make a decision, the standard procedure was to hold a series of sessions in which no conclusion was made. When judgments were made, they were usually scrutinized by so many people that no single individual could be held responsible. An attempt to speed up decision-making through restructuring—by combining important leaders with subject-matter experts in newly established central and regional centers of excellence—became yet another stumbling block. Key management were still unsure of their legal right to use these centers, so they didn’t.

Second-Guessing Was An Art Form: By The Time Choices Were Made, They Had Been Scrutinized By So Many People That No Single Person Could Be Held Responsible

The nonprofit’s board of directors and administration went back to the drawing board. They created a decision-making map, a tool to assist identify where different sorts of decisions should be made, and as a result, decision rights were defined and reinforced at all levels of management. Following that, all managers were urged to delegate standard operational responsibilities. Holding people accountable for their judgments felt fair after they had a clear understanding of what decisions they should and should not be making. Furthermore, they could now concentrate their efforts on the organization’s objective. Clarifying decision rights and responsibilities also improved the organization’s capacity to track individual accomplishment, allowing it to map new and exciting career routes.

Information Is Freely Exchanged Across Supply Chain Organizational Lines

Units function like silos when information does not flow horizontally across different parts of the firm, preventing economies of scale and the transfer of best practices. Furthermore, the company as a whole misses out on the chance to cultivate a cadre of up-and-coming managers who are well-versed in all sectors of the business. According to our findings, only 21% of respondents from poor-execution organizations believed information flowed smoothly across organizational boundaries, whereas 55% of respondents from strong-execution companies did. However, since even the strongest organizations have low scores, this is an issue that most businesses can address.

A cautionary tale comes from a B2B company whose customer and product teams failed to work together to serve a critical segment: large, cross-product clients. The corporation had built a customer-focused marketing organization to handle connections with significant clients, which devised customer outreach initiatives, novel pricing models, and targeted promotions and discounts. However, this group could not provide clear and consistent reporting to the product units on its initiatives and success, and it had trouble gaining time with frequent cross-unit management to discuss major performance issues. Each product unit communicated and planned in its own way, and it needed a lot of effort on the part of the customer group to comprehend the diverse priorities of the units and customize communications to each of them. As a result, the units were unaware of, and had little faith in, this new division’s efforts to penetrate a vital consumer category. The customer team, on the other hand (and appropriately), believed the units paid only cursory attention to its plans and couldn’t elicit their cooperation on topics important to multiproduct clients, such as potential trade-offs and volume discounts.

This lack of collaboration had previously not been an issue because the company was the leading player in a high-margin area. Customers began to perceive the firm as unreliable and, in general, a tough supplier as the market became more competitive, and they became increasingly hesitant to enter into beneficial partnerships.

However, once the flaws were identified, the remedy was rather simple, requiring just that the groups communicate with one another. The customer division was tasked with providing regular reports to the product units that detailed performance versus targets by product and geographic location, as well as a root-cause investigation. Every quarter, a standing performance-management meeting was added to the calendar, providing a space for face-to-face information exchange and discussion of unresolved concerns. These actions fostered the larger organizational trust that collaboration requires.

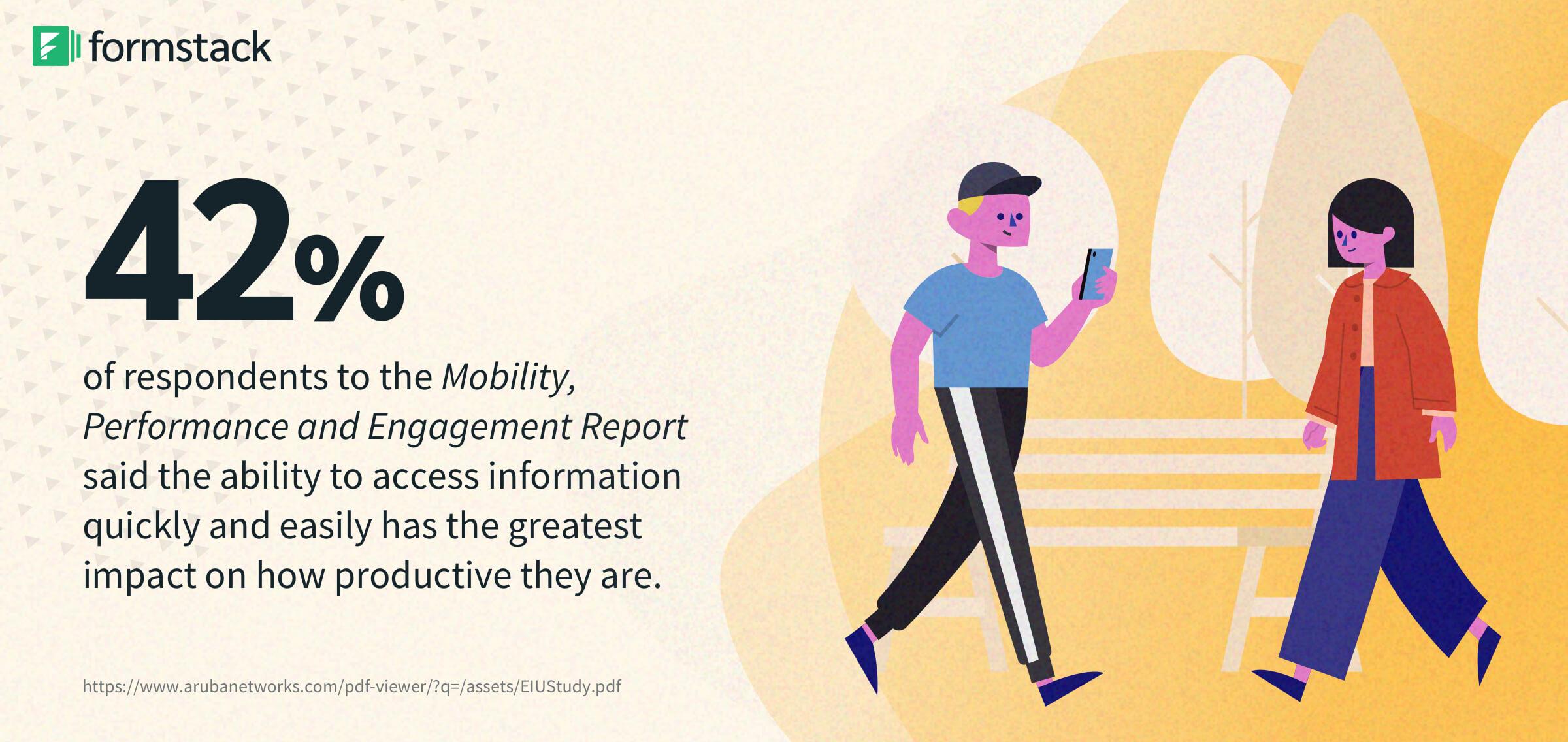

Field And Line Employees Typically Have Access To The Data They Need To Understand The Financial Impact Of Their Daily Decisions

Employees’ ability to make rational decisions is inevitably limited by the information available to them. Global Supply Chain managers will always pursue incremental revenue if they don’t know how much it will cost to grab an additional dollar in revenue. They can hardly be blamed, even if their judgment is incorrect in the light of all available evidence. According to our research, 61% of people in high-execution firms believe field and line employees have the information they need to comprehend the financial effect of their decisions. In firms with poor implementation, this figure drops to 28%.

We witnessed this unfavorable dynamic at a large, diversified financial-services customer that had grown through a series of successful acquisitions of small regional banks. Managers preferred to split front-office bankers who marketed loans from back-office support groups who performed risk assessments when combining operations, putting each in a different reporting relationship and, in many cases, in different locations. Regrettably, they did not establish the required information and motivational ties to ensure that operations ran well. As a result, they pursued separate, and frequently conflicting, objectives.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Responsibility Awareness

Clearly Define Roles And Responsibilities

The single most significant quality indicated for effective plan implementation was ensuring that “everyone has a good knowledge of the decisions and actions he or she is responsible for.” Why?

Individual decisions make up a firm, and individual decisions make up successful strategy implementation. Responsibilities are usually apparent in a small business. However, as the firm grows, so does the number of people, and the number of jobs and duties expands and spreads. Meanwhile, bosses are becoming increasingly disconnected from their employees’ day-to-day tasks.

Individual decisions make up a firm, and individual decisions make up successful strategy implementation.

Who is to blame for what is no longer obvious?

Things can get extremely muddled in global corporations with similar teams in different parts of the world. Who, for example, makes the decisions when designing a product for a specific market? Is it better to work with a global team or a local team? Conflict and ambiguity become rampant, impeding any forward movement.

What are some ways to make the roles of individuals and teams more clear?

Create a clear structure that identifies who has the authority to make choices (for both departments and individuals) and communicates this to the entire organisation. Allow individuals to complete projects before promoting them to new positions; this reduces crossover – the perplexing period when a new manager arrives but the old management can’t let go of the project they were working on.

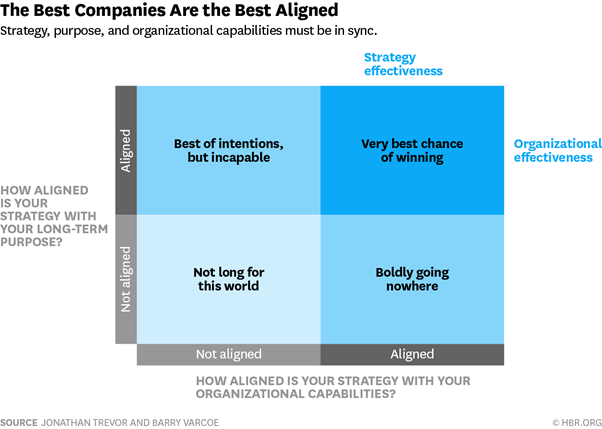

Chapter 2: Team Alignment

What Are The Benefits Of Strategic Alignment For Strategy Execution?

A few handpicked executives would create a strategy initiatives cabal and scale the mountain to meeting room C back in the strategy dark ages. They would emerge weeks later with a stone tablet engraved with the new strategic objectives. They may have also thrown a pizza party (but we can’t be sure because no employees were invited).

The task has been completed, and the approach has been implemented. So they reasoned. This top-down, prehistoric approach to strategy, however, does not function in the actual world. Thankfully, in recent years, there has been a shift in strategy.

If your firm sets rigid strategy goals without taking into account the strategic alignment process, you’re setting yourself up for a hot new recipe for failure at every turn. Let’s take a look at the drawbacks of bad strategic alignment.

What Are The Ramifications Of A Strategy That Isn’t Aligned?

When company leaders keep strategy planning to themselves, the result is a tone-deaf shambles. It becomes unrecognisable after being distilled so far from its source.

Then, like some strange totem pole, this complicated “plan” is thrust at staff. The businessmen wrap their neckties over their heads and shout ‘this is the future…’ in a rhythmic manner. A wide-eyed CEO thumps an ominous beat on the bongo under the flickering light of a 417-slide PowerPoint presentation on the antiquated projector, as puzzled (and terrified) staff place matchsticks in their eyes to keep awake.

Okay, we may be prone to exaggeration (sometimes), but it’s reasonable to say that staff buy-in is low. With such a strategy in place, business units strive to ‘Exceed Success’ or ‘Awesomize the Day,’ but because there is no coordination or communication across departments, everyone goes their own way, and the organization’s goals are left to project conflicts and isolated teams.

Employees are frustrated and disengaged from the leadership’s vision in this climate. Isolated skill becomes stagnant, and demotivation is rampant. Some people quit, staplers go missing, and Netflix viewing time in the office skyrockets.

Employee engagement plummets, and performance suffers as a result. People are unsure of what they should do and are less willing to put forth an effort.

What was the end result? Countless hours, dollars, and talents have been squandered.

A lack of strategic alignment has rendered strategy execution difficult to attain and pointless to pursue in this scenario. Every attempt by management to gain support is a costly endeavour that results in more animosity than return on investment.

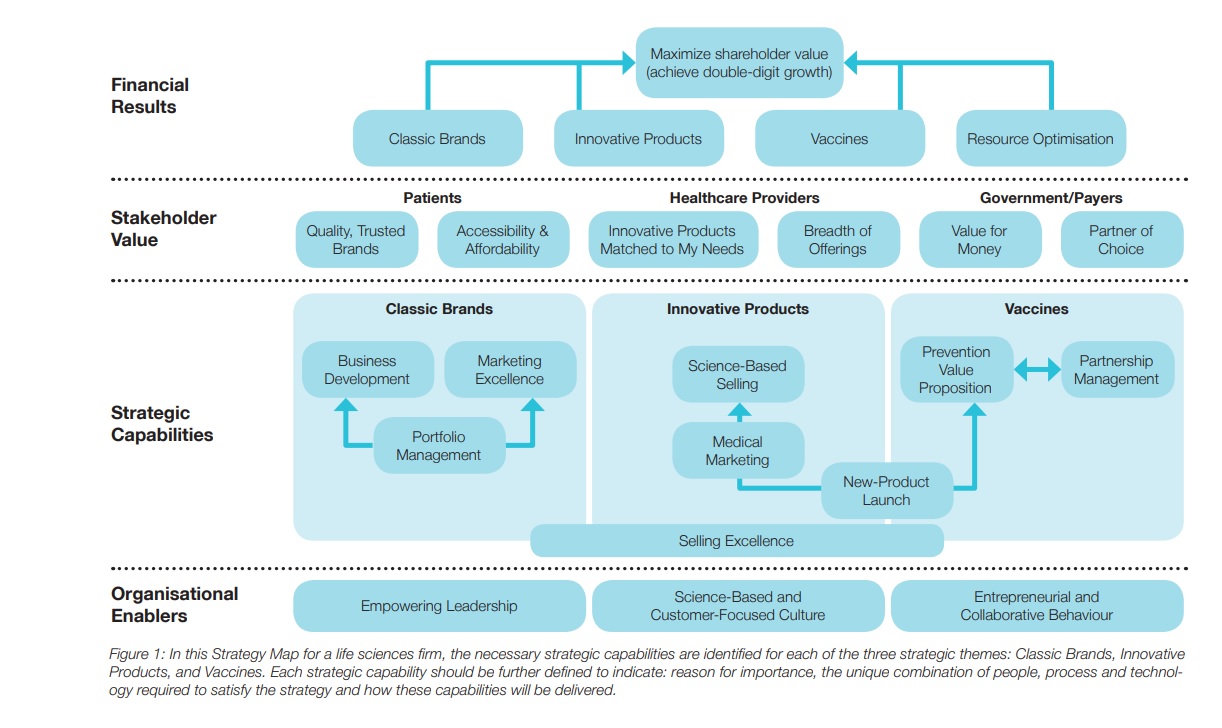

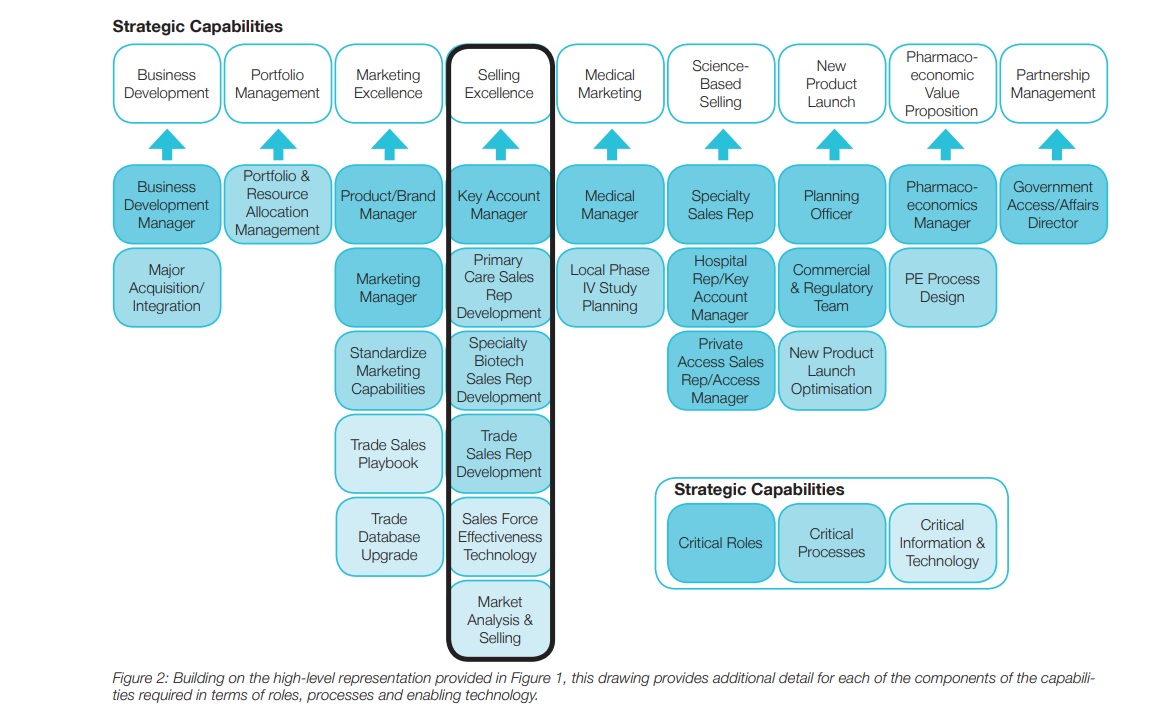

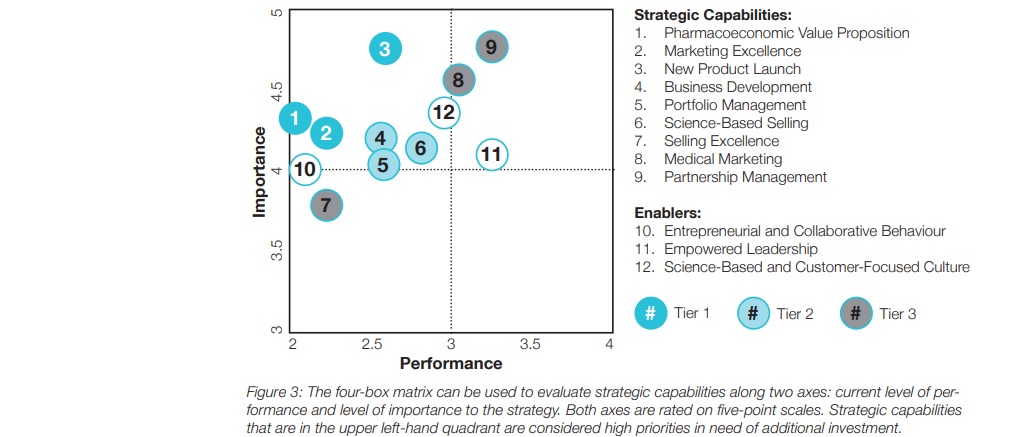

Chapter 3: Assess Capabilities

Capacity Of Organisations

Organizations that successfully unlock capacity to execute new growth initiatives see a 77 percent boost in profitability. To achieve plan implementation success, strategists must focus on unlocking capacity.

Many businesses fail to commit sufficient resources (assets, time, people, etc.) to the implementation of new growth initiatives. They place an excessive amount of emphasis on strategy development, planning, performance measures, and communication.

Strategists must identify places where the organization’s capacity to execute is compromised owing to a lack of coordination. The net outcome of poor coordination is a decrease in the enterprise’s entire capability.

• Deploy diagnostics to measure organisational capacity before starting growth efforts to unlock organisational capacity.

• Use new technologies to better understand mid-manager trade-offs when it comes to resourcing growth bets.

• Create new frameworks for releasing resources that have been trapped.

• Establish support systems to aid in the integration of expansion initiatives into existing enterprises.

Chapter 4: Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

Strategy planning and execution is all about making decisions about the organization’s future path; business intelligence is all about delivering insight to help those decisions. Dashboards become a needless complication at best and a misleading distraction at worst if these things are not firmly integrated. However, there is a five-step approach that is both efficient and produces high-impact results.

1. Begin with the company’s business plan. Start by outlining the particular goals that the organisation will need to attain in order to carry out its plan. Both dashboard developers and business users must be willing to frame their interactions in terms of how the company will get there.

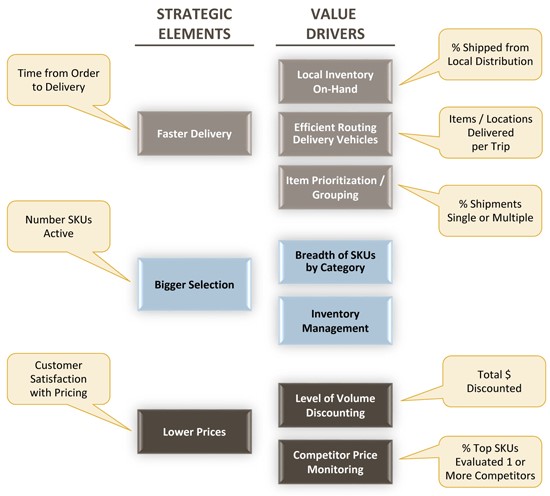

2. Determine the most important value drivers. Create a value tree by determining which skills you’ll need to execute well, as well as the activities you’ll need to accomplish properly. Then decide which of those are the most crucial. Unbundling the organization’s strategy creates a direct relationship to the plan and prioritises what leadership should be monitoring.

3. Make a list of connected decisions and queries. List the most significant questions that must be asked and answered, as well as the major decisions that must be made, focusing on the critical drivers. It’s vital to spend time understanding how leaders and business users will utilise the dashboard in order to get the focus and design just right.

4. Identify the metrics that matter. Determine the primary data source and format required after identifying the measures that will give the information needed for each inquiry and decision. This is an opportunity to discover and close data quality and availability gaps. Everything you do now, once again, ties back to the plan, so any investments you make now will be very targeted and impactful.

5. Create designs that present data in a way that elicits essential insights and addresses a variety of business circumstances. Review and iterate designs with leaders and users, and test for utility on a regular basis. Create a design that facilitates decision-making.

These five simple procedures will provide your team with the knowledge they need to more effectively monitor and change your strategy’s implementation, resulting in increased growth, profitability, and achievement of organisational goals.

Chapter 5: Decision Acceptance

Why Is Strategy Dependent On Commitment?

Why is commitment so important, and how can an organisation obtain and maintain it?

Senior management and key individuals throughout the organisation must be committed to moving the company ahead in order to achieve its goals. As a result, they have made a commitment to the company’s success. They also ensure that the organization’s strategies are carried out as efficiently as possible. Finally, their behaviours show their level of dedication and motivate people around them to succeed.

What Is The Significance Of Commitment?

In today’s competitive world, an organization’s ability to define and execute its strategy, mission, goals, and objectives is critical. Anything less could open the door for its competitors to gain market share, hurting the company’s performance.

There are also more human reasons to anticipate commitment.

The organisation underlines its commitment to each individual by having high standards and taking activities to reinforce them. Also, unless there is a two-way commitment between the individual and the firm, setting high goals and having individuals realise them is tough.

For the organisation to be competitive, the individual must commit to doing well.

The organisation must provide its employees with the tools and support they require in order for them to succeed in their roles. First, whenever possible, include individuals in the company’s decision-making processes. Many people have good suggestions on how to enhance things or what new things the company should undertake. Second, solicit their thoughts and provide positive comments, even if their suggestion is not currently feasible for the organisation.

How Can A Company Gain And, More Crucially, Maintain Commitment Over Time?

First and foremost, provide the employee with the tools and authority they require to perform their duties efficiently. Furthermore, provide them with the necessary support so that any mistakes they make become a learning opportunity rather than a punishment. Finally, create a culture that encourages dedication rather than tearing it down. This begins at the top of an organisation and can be one of the most important factors in the company’s ultimate success.

Chapter 6: Strategy Flow

CEOs Must Deal With Information Flow Throughout Their Organisations

Michael Watkins’ book, The First 90 Days, contains a lot of practical ideas and methods and is an invaluable tool for new leaders at all levels. It’s also beneficial for new hires, established employees who are taking on new responsibilities, and internal high performers who want to advance faster.

However, something is missing, especially for CEOs. And the missing piece in Watkins’ book has a significant impact on the CEO’s ability to lead the business in strategy execution.

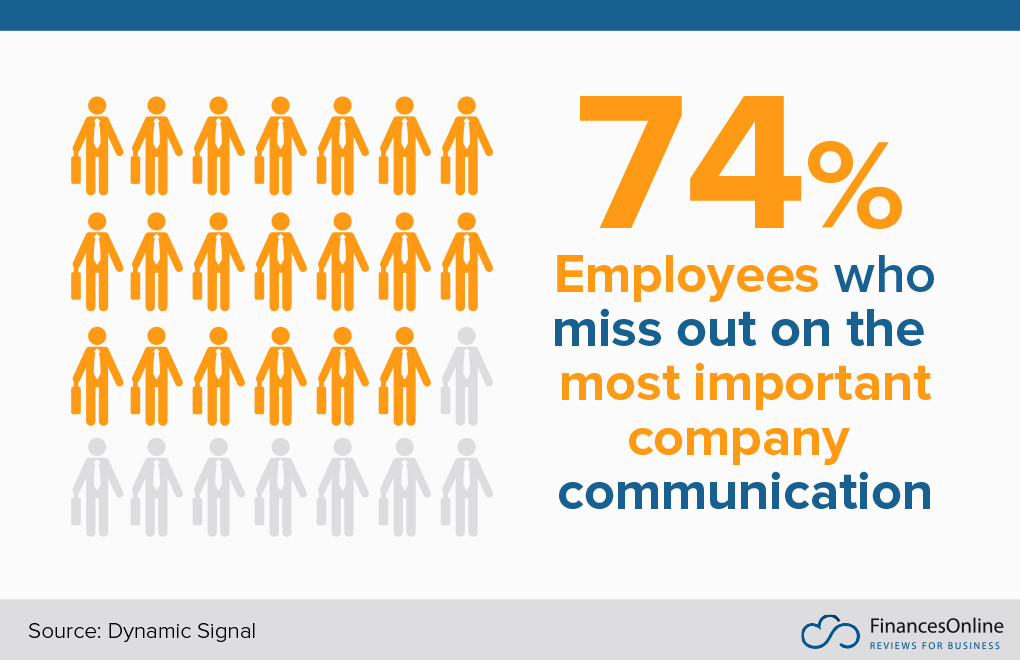

“Enterprises fail at execution because they…neglect the most powerful drivers of effectiveness — decision rights and information flow,” according to Gary Neilson, Karla Martin, and Elizabeth Powers’ research (June 2008, Harvard Business Review). Furthermore, just two-thirds of employees at high-performance businesses believe that significant strategic decisions are effectively (and swiftly) put into action, according to their findings. Only 55% of those same companies stated that information moved freely. These are the ‘good people,’ after all!

Surprisingly, that’s exactly what Watkins overlooked—and what CEOs must address.

Watkins keeps the conversation focused on making decisions as part of developing a team; while this is crucial at any level, it’s only part of the issue for CEOs. CEOs, whether new or seasoned, set the tone for how decisions will be made, build decision-making frameworks, and ensure that decisions are followed through on. This includes defining who has decision-making authority and under what conditions. It’s also about deciding which decision style is best for the situation — autonomous, consultative, consensus, or majority. Basically, think about how you’ll make your decision before you make it. Explicitly stating how a decision will be made outlines the role of others in the decision-making process and promotes transparency. As a result, people gain trust and acceptance since they understand how you arrived at your conclusion, regardless of whether they agree with or approve of it. Simply put, implementing a decision – and a strategy – that you understand and accept is easier.

The quality and timeliness of decisions are influenced by the flow of information. Decision-makers have all they need to make timely, high-quality decisions when information flows efficiently and effectively. After decisions are made, information flow has an impact on decision alignment and acceptability. This necessitates conveying choices across the organisation and in different directions — vertically within units, horizontally across units, and across to link interdependent teams or work flows.

Furthermore, CEOs must swiftly determine whether key leaders will follow through on choices and effectively exchange information. Decisions that are often ignored, second-guessed, or changed without adding value are not adopted; they obstruct strategy implementation. Similarly, bottlenecks in the flow of information create silos, stifle the transfer of best practises, and stifle the professional development of your future leaders. Blind spots are also created by a lack of information flow, which can be a costly mistake in plan execution.

What have the most successful CEOs discovered? They’ve figured out how to evaluate their company’s performance in terms of decision rights and information flow. Consider the following questions:

• Is everyone aware of who is responsible for which decisions? (decision-making authority)

• Is the appropriate data reaching the right people at the right time, allowing for good decisions? (information flow)

• Is everyone on the same page about the decision? (alignment)

• Has the decision been accepted by all of the leaders? (alignment)

• Has the decision been conveyed to the appropriate individuals at the appropriate time so that it can be carried out as planned? (information flow and decision rights)

• Are your senior leaders aware of their responsibilities in putting the decision into action? (decision rights and information flow)

• Is everyone aware of what will happen if the decision is not followed? (accountability)

If you responded ‘no,’ dig a little more to figure out what’s getting in your way. Then, to determine core causes, look for patterns or themes in all of your responses. CEOs can then devise a strategy to address the problem and get strategy execution back on track, whether it’s in the first 90 days, the last 90 days, or somewhere in between.

Chapter 7: Employee Engagement

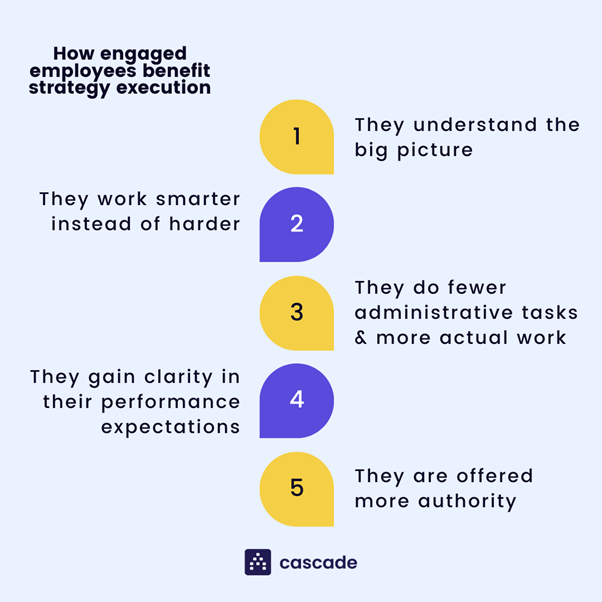

Employee engagement, according to a recent i4CP study, can be the key to achieving high performance in firms. Employee engagement was also recognised as a key differentiator between successful and low-performing firms in the study.

So, how do you go about doing it?

There are four major steps that should be taken to promote staff engagement and strategy execution:

1. Clarity of Objectives

One of the reasons why employees are unable to engage with a specific business plan is that they do not fully comprehend it. While management and certain stakeholders may be aware of why a plan is being executed, this information may not reach the team that is carrying it out. If they don’t have that, the work they accomplish won’t be as good as it could be.

So, if you want your employees to be involved and invested in the successful implementation of a strategy, you need clear, succinct goals.

2. Assign Appropriate Roles

Once the goals are defined, make sure that everyone on the team understands their position in the strategy. While the grand vision is crucial, daily execution necessitates smaller, measurable deliverables that provide staff with a clearer perspective of what they must do. This creates an immediate sense of involvement and comprehension of how their abilities fit into the bigger picture.

3. Employee Empowerment

Having a goal to reach but no way to achieve it, whether in terms of freedom to test new ideas or resources to put those ideas into action, can soon lead to dissatisfaction with the objective. As a result, you must ensure that your staff have everything they require to complete the tasks that have been assigned to them.

Empowering your staff would entail the following:

• Fostering an environment in which fresh ideas are welcomed

• Trusting them to come up with worthwhile ideas and allowing them the flexibility to test them out

• Providing them with all the resources they need to bring their ideas to life through seminars and trainings.

4. Good Performances Should Be Applauded and Recognized

It’s vital to use positive reinforcement to keep your personnel interested in your goals and methods. Utilize competition to increase employee engagement and to recognise and reward outstanding ideas and performance.

It’s also crucial to think about how you quantify employee participation when it comes to praise and recognition. Employees, according to Holly Green, CEO of The Human Factor Inc., cannot relate to examples of their effort resulting in sales or monetary gains for the company. As a result, it’s preferable if appreciation is expressed in terms of how an employee’s efforts influenced more tangible measures like conversion, delivery or response times, or customer service.

Chapter 8: Transformation Program

Six Fundamental Principles

To be successful in a transformation programme, there are six key rules to follow:

1. Management of Change

The transition should be orchestrated by change agents, who should consider the behavioural aspects of change. Change agents should be able to halt and resume projects, as well as adjust the pace of execution and the pattern of programme plans based on the behavioural components of change.

2. Alliances

If this alliance cannot be formed, the programme will almost certainly fail. Detailed planning should not begin until the alliance has been formed.

3. Management of Risk

Uncertainty is inherent in change. People’s sense of security is undermined by uncertainty; as a result, ‘constants’ must be clearly established to steer the organisation through change.

Quick wins that underpin the benefits of behavioural change and maintain its fundamental goal are examples of constants:

• An understanding justification for the change

• A clear vision

• A decision-making principles and priorities set

4. Establishing a Roadmap

It’s vital to understand that programme milestones should be assessed while keeping in mind that tactical points along the plan will shift as stakeholders’ perspectives shift, demanding a long-term commitment at milestones.

5. Participation of essential stakeholders

People will never change their conduct merely because it is demanded of them. They must comprehend why they should, as well as the potential rewards of changing, and they must be involved in selecting what the new behaviours would entail. It will be necessary to maintain an open and ongoing communication.

Environmental Factors

Early on, close attention should be taken to detect early warning signs of programme failure (e.g., inspiration and motivation toward vision, understanding of programme goals, trust, shared approach, and schedule acceptance).

Chapter 9: Leadership Roles

Leadership is essential for developing and implementing strategy; without it, excellent strategy is impossible to achieve.

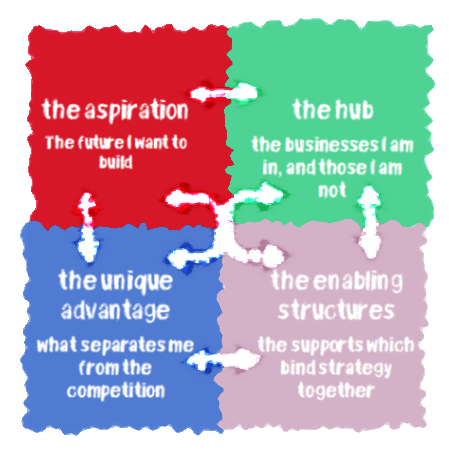

Examining strategy through the prism of leadership concentrates the discussion on the important duties that a leader must perform in order to develop and implement strategy. Managers may discover that some strategic tasks, such as industry study, competitor analysis, and internal analysis, fall to second place as a result of this focus because it is not as critical for the leader to perform them as it is to ensure that they are completed. This chapter focuses on the five primary steps of the strategy-making/strategic-execution process: establishing a vision and mission, setting goals and objectives, crafting a plan, executing the strategy, and evaluating performance. Finally, we discuss what qualities a leader must possess in order to lead effectively.

Creating a Strategic Vision and Mission Statement

Vision is at the centre of strategy and at the essence of leadership. The task of the leader is to develop a vision for the company that will engage both the imagination and the energies of its employees. “An effective leader knows that the ultimate task of leadership is to create human energies and human vision,” Peter Drucker puts it succinctly. The vision must be linked to the firm’s principles, and the leader must do it in a way that the rest of the company can understand, grasp, and support. The enterprise is moved by vision; the enterprise is stabilised by values. Values look to the past, while vision looks to the future.

Chapter 10: Scorecards

The Balanced Scorecard: An Overview

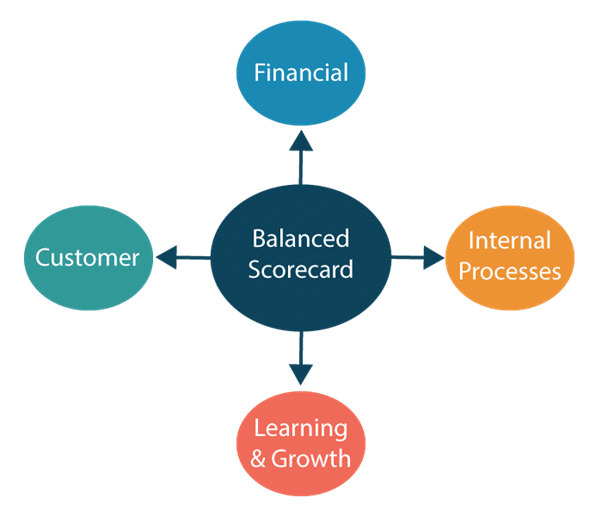

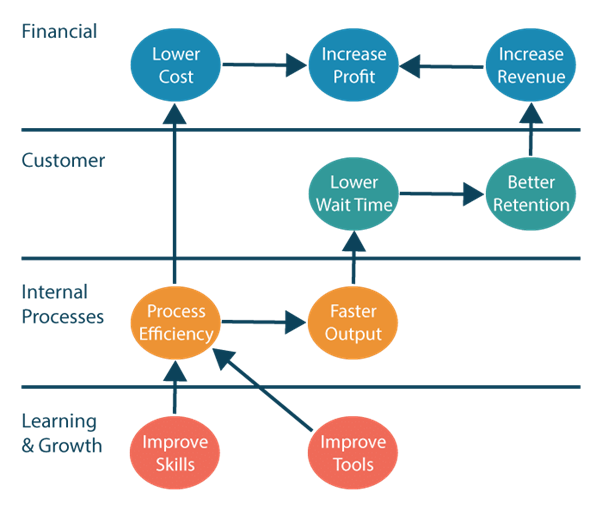

One of the most well-known strategy frameworks ever devised is the Balanced Scorecard.

Since its inception in the 1980s, when Robert Kaplan and David Norton created it, it has been used by thousands of organisations. It’s also one of the first topics covered in a business or management degree programme.

Despite its widespread use, the Balanced Scorecard is frequently misunderstood or poorly executed. We’ll show you how to apply the Balanced Scorecard Model (and report on it) in a way that adds real business value to your company in this tutorial.

What Is A Balanced Scorecard, And How Does It Work?

The Balanced Scorecard simply asks companies to develop a set of internal measures to assist them evaluate their business performance in four major areas (also known as “perspectives”):

Financial

Cash flow, sales performance, operating income, and return on equity are all common scorecard indicators.

Customer

With scorecard metrics including new product sales as a percentage of total sales, on-time delivery, net promoter score, and share of wallet.

Internal Business Methodologies

This would entail calculating unit costs, cycle times, yield, and mistake rates, among other things.

Learning and Development

Employee engagement scores, high-performing employee retention rates, staff competence gains, and so on are examples of measures.

What are the Advantages of Using a Balanced Scorecard?

The Balanced Scorecard’s four viewpoints serve a variety of functions.

To begin with, they demand that businesses ‘balance’ their efforts amongst the primary drivers of corporate performance. They also compel companies to give concrete KPIs to each perspective, so enhancing accountability.

Finally, they provide a structure for expressing an organization’s strategy to external stakeholders. ‘We’re doing x because it helps us succeed in our scorecard’s Customer viewpoint,’ for example.

According to one survey, the Balanced Scorecard is used to measure business performance by around 64% of firms in the United States.

We observe a similar level of popularity among the thousands of clients that have strategic plans in our own strategy system, Cascade. Interestingly, we frequently discuss with clients about how they’re implementing the Balanced Scorecard just to find out that they haven’t even realised they’ve done so.

Instead, they’ve naturally arrived at the conclusion that they need to focus their efforts and measures on roughly the same four viewpoints that the Balanced Scorecard recommends.

Finally, applying the Balanced Scorecard has the advantage of forcing your organisation to maintain a level of concentration that includes both leading and trailing KPI indicators (more on that later).

Chapter 11: Inclusive Planning

Is your strategic planning process open to all stakeholders?

Isn’t the gap between strategy and result generally too wide?

Don’t we consider implementation and execution as part of the strategic planning process?

If we don’t, we’ll be opening the door to the dreadful chasm.

However, not everyone involved in the plan must also be involved in the execution. For each phase, we simply need the proper individuals. However, it should ideally be weighted toward inclusion, else we risk creating a second chance for the gap.

Solutions

Let’s begin with the procedure we recommend, which is outlined below:

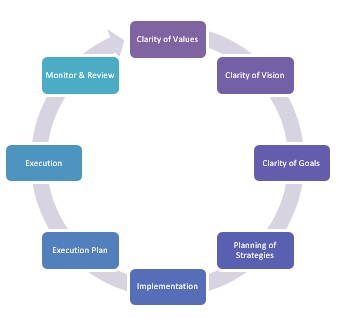

It’s also vital to understand the differences between the parts.

• Planning is an activity that occurs at every stage of the process, but it is especially important for agreeing on strategies and ensuring that they are executed in a coordinated manner.

• Values — the spiritual, mental, and behavioural principles that must not be violated. We will develop a values gap if we don’t get this right, which will lead to an outcomes gap.

• Vision – a clear understanding of our goals – our compass.

• Objectives – short-term objectives that are consistent with our beliefs and vision.

• Strategy – the big picture milestones we need to hit in order to meet our objectives.

• Implementation – the activity of communication and accountability to ensure that execution and strategy are in sync.

• Execution – the operational or tactical activity that is carried out in order to attain the objectives.

• Monitoring and Reviewing – necessary measurement and review to allow for adjustments, adaptation, correction, and innovation.

Who Should Be In Attendance?

All planning should, ideally, include the leaders of each phase. It’s all too frequent for a senior leader group to decide on a strategy that an execution leader subsequently finds unfeasible owing to a resource or competence gap that the strategists anticipated was either existent or not needed.

In contrast, if the implementation plan is comprehensive, the presence of top leaders at execution planning is reduced.

These criteria can be used to determine who should be present throughout each phase’s planning:

• How can we ensure that clarity is consistent?

• What is the most effective way to replace assumption with direct knowledge?

• How can we make the flow of intention and action more aligned?

The Planning Process

Regardless of the phase being planned, an expert planning facilitator who does not contribute material but assures complete engagement, procedural adherence, and clarity of decisions is required.

The participants can then concentrate entirely on their input.

Conclusion

Too many strategic planning processes exclude critical phases and fail to include the right personnel. They are the primary causes of the misalignment of strategy and execution.

Chapter 12: Middle Management

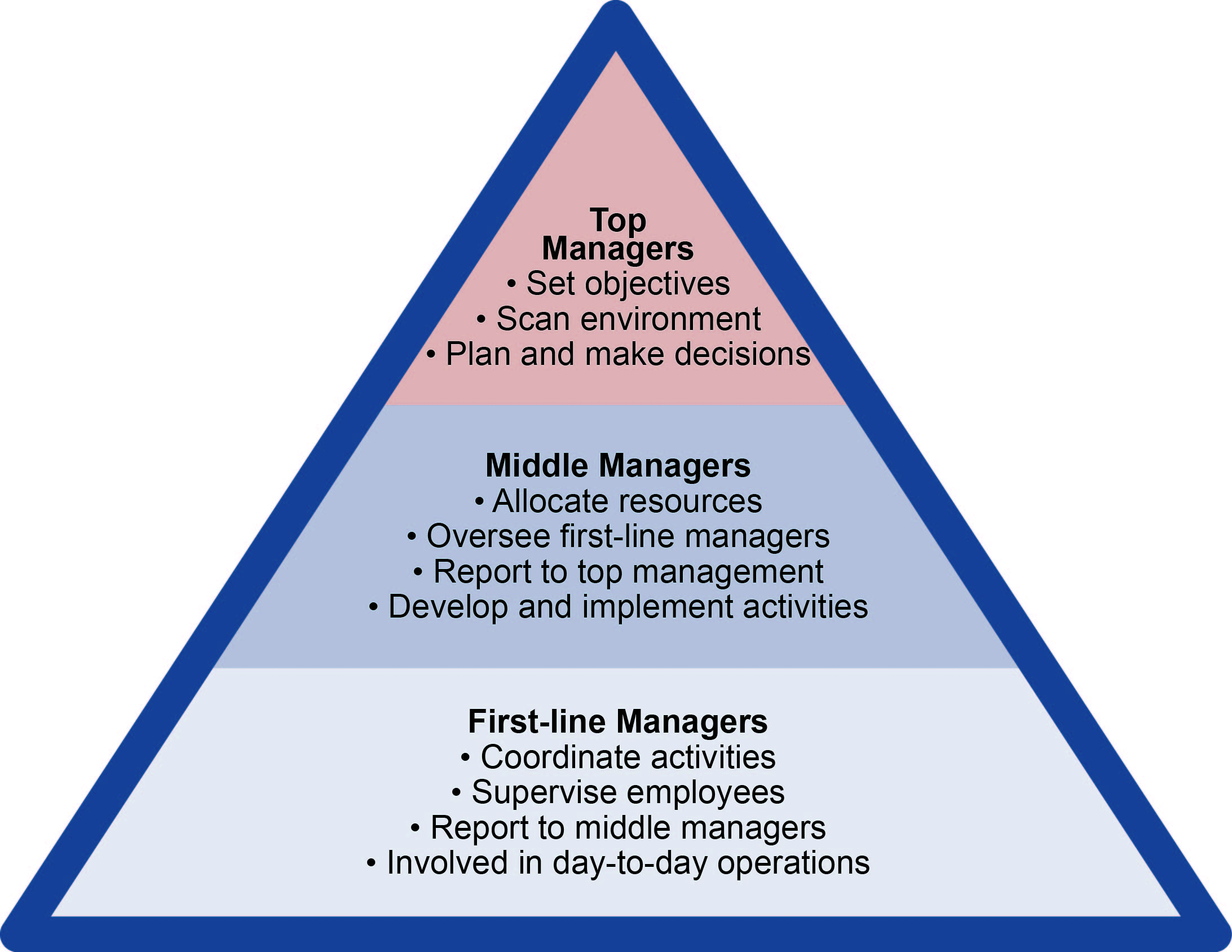

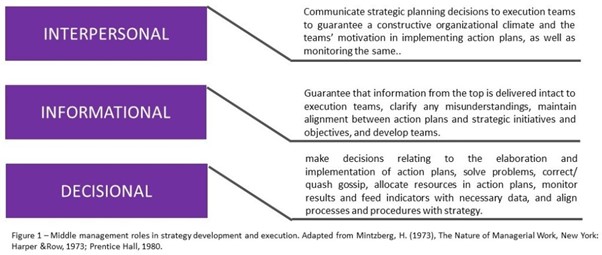

Middle managers’ contributions to strategy implementation can make or break your strategic plans.

Success in Putting the Strategy into Action

Strategic clarity, believability, and implementability account for 31% of the difference between good and low performing teams and organisations, according to our organisational alignment research. That involves getting all important stakeholders — notably middle managers — on board with where you’re going, why your strategic direction makes sense, and how you plan to get there (not just the leadership team).

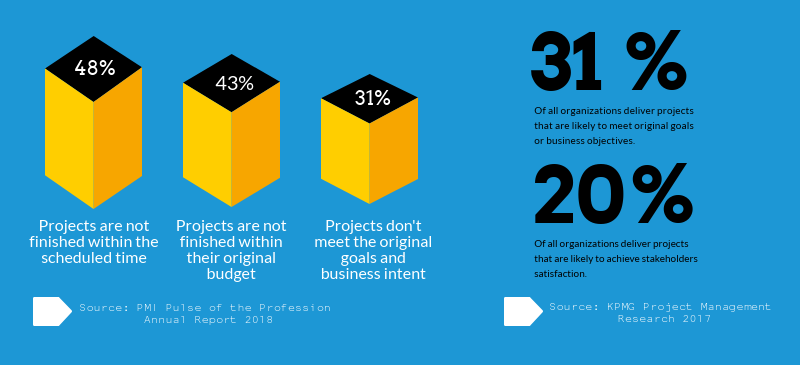

A Disastrous Track Record

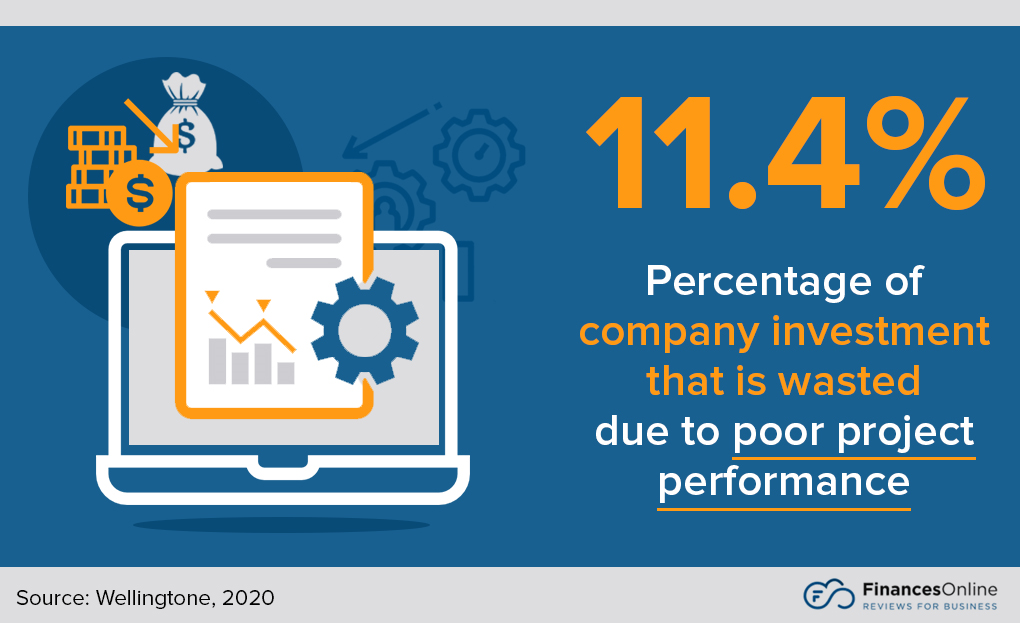

Leaders tell us time and time again that their carefully written strategy plan is not being implemented with the quality or speed that they anticipate to achieve the desired objectives. According to the research, plan implementation has a dismal track record:

• According to IBM, only about 10% of well-formulated plans are properly implemented.

• According to a Booz & Company poll, 49% of executives indicated their organisations had no strategic priorities.

• Employees polled say the organization’s strategy is 50% less clear than its managers believe.

People and culture must be considered when developing strategies.

A corporate strategy must be properly implemented in order to create a genuine and beneficial difference. It must go through your people and workplace culture to be efficiently accomplished. While CEOs are ultimately responsible for achievement, they are unable to carry out plans on their own.

They require the active participation of middle management.

Why Are Middle Managers So Crucial?

Executives must rely on their personnel for a successful implementation. Middle management is the best link between CEOs and their staff. The better your odds of successful strategy implementation are, the more effectively you can engage middle managers, convey the plan clearly, assure their knowledge, and gain their full buy-in.

“Middle managers are central to strategy execution,” says Bharat Anand, a Harvard Business School professor of business administration. Indeed, in a survey of more than 500 business leaders, more than 60% said that a lack of middle manager participation was a major roadblock to strategy implementation at their companies. The importance of middle managers in plan implementation cannot be overstated.

Managers Should Be Actively Involved

The strategic priorities must be agreed upon and committed to by managers. Middle managers are responsible for converting high-level strategies into daily decisions and actions that have an impact on customers and staff. Your strategy is nothing more than wishful thinking without their dedication and support.

Final Thoughts

It’s not easy to carry out a strategy. It requires a plan that is well-understood and supported by all employees. Middle managers, in particular, must be actively involved and fully engaged if employees are to pull in the same direction collectively. Do not underestimate the importance of middle managers in the implementation of strategy.

Curriculum

Global Supply Chain – Workshop 12 – Strategy Execution

- Responsibility Awareness

- Team Alignment

- Assess Capabilities

- KPI’s

- Decision Acceptance

- Strategy Flow

- Employee Engagement

- Transformation Program

- Leadership Roles

- Scorecards

- Inclusive Planning

- Middle Management

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Global Supply Chain corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast

As a guide, the Appleton Greene Global Supply Chain corporate training program should take 12-18 months to complete, depending upon your availability and current commitments. The reason why there is such a variance in time estimates is because every student is an individual, with differing productivity levels and different commitments. These differentiations are then exaggerated by the fact that this is a distance-learning program, which incorporates the practical integration of academic theory as an as a part of the training program. Consequently all of the project studies are real, which means that important decisions and compromises need to be made. You will want to get things right and will need to be patient with your expectations in order to ensure that they are. We would always recommend that you are prudent with your own task and time forecasts, but you still need to develop them and have a clear indication of what are realistic expectations in your case. With reference to your time planning: consider the time that you can realistically dedicate towards study with the program every week; calculate how long it should take you to complete the program, using the guidelines featured here; then break the program down into logical modules and allocate a suitable proportion of time to each of them, these will be your milestones; you can create a time plan by using a spreadsheet on your computer, or a personal organizer such as MS Outlook, you could also use a financial forecasting software; break your time forecasts down into manageable chunks of time, the more specific you can be, the more productive and accurate your time management will be; finally, use formulas where possible to do your time calculations for you, because this will help later on when your forecasts need to change in line with actual performance. With reference to your task planning: refer to your list of tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve your program objectives; with reference to your time plan, calculate when each task should be implemented; remember that you are not estimating when your objectives will be achieved, but when you will need to focus upon implementing the corresponding tasks; you also need to ensure that each task is implemented in conjunction with the associated training modules which are relevant; then break each single task down into a list of specific to do’s, say approximately ten to do’s for each task and enter these into your study plan; once again you could use MS Outlook to incorporate both your time and task planning and this could constitute your study plan; you could also use a project management software like MS Project. You should now have a clear and realistic forecast detailing when you can expect to be able to do something about undertaking the tasks to achieve your program objectives.

Performance management

It is one thing to develop your study forecast, it is quite another to monitor your progress. Ultimately it is less important whether you achieve your original study forecast and more important that you update it so that it constantly remains realistic in line with your performance. As you begin to work through the program, you will begin to have more of an idea about your own personal performance and productivity levels as a distance-learner. Once you have completed your first study module, you should re-evaluate your study forecast for both time and tasks, so that they reflect your actual performance level achieved. In order to achieve this you must first time yourself while training by using an alarm clock. Set the alarm for hourly intervals and make a note of how far you have come within that time. You can then make a note of your actual performance on your study plan and then compare your performance against your forecast. Then consider the reasons that have contributed towards your performance level, whether they are positive or negative and make a considered adjustment to your future forecasts as a result. Given time, you should start achieving your forecasts regularly.

With reference to time management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual time taken in your study plan; consider your successes with time-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; consider your failures with time-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to time planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your time expectations. You need to be consistent with your time management, otherwise you will never complete your studies. This will either be because you are not contributing enough time to your studies, or you will become less efficient with the time that you do allocate to your studies. Remember, if you are not in control of your studies, they can just become yet another cause of stress for you.

With reference to your task management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual tasks that you have undertaken in your study plan; consider your successes with task-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case; take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; consider your failures with task-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to task planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your task expectations. You need to be consistent with your task management, otherwise you will never know whether you are achieving your program objectives or not.

Keeping in touch

You will have access to qualified and experienced professors and tutors who are responsible for providing tutorial support for your particular training program. So don’t be shy about letting them know how you are getting on. We keep electronic records of all tutorial support emails so that professors and tutors can review previous correspondence before considering an individual response. It also means that there is a record of all communications between you and your professors and tutors and this helps to avoid any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation. If you have a problem relating to the program, share it with them via email. It is likely that they have come across the same problem before and are usually able to make helpful suggestions and steer you in the right direction. To learn more about when and how to use tutorial support, please refer to the Tutorial Support section of this student information guide. This will help you to ensure that you are making the most of tutorial support that is available to you and will ultimately contribute towards your success and enjoyment with your training program.

Work colleagues and family

You should certainly discuss your program study progress with your colleagues, friends and your family. Appleton Greene training programs are very practical. They require you to seek information from other people, to plan, develop and implement processes with other people and to achieve feedback from other people in relation to viability and productivity. You will therefore have plenty of opportunities to test your ideas and enlist the views of others. People tend to be sympathetic towards distance-learners, so don’t bottle it all up in yourself. Get out there and share it! It is also likely that your family and colleagues are going to benefit from your labors with the program, so they are likely to be much more interested in being involved than you might think. Be bold about delegating work to those who might benefit themselves. This is a great way to achieve understanding and commitment from people who you may later rely upon for process implementation. Share your experiences with your friends and family.

Making it relevant

The key to successful learning is to make it relevant to your own individual circumstances. At all times you should be trying to make bridges between the content of the program and your own situation. Whether you achieve this through quiet reflection or through interactive discussion with your colleagues, client partners or your family, remember that it is the most important and rewarding aspect of translating your studies into real self-improvement. You should be clear about how you want the program to benefit you. This involves setting clear study objectives in relation to the content of the course in terms of understanding, concepts, completing research or reviewing activities and relating the content of the modules to your own situation. Your objectives may understandably change as you work through the program, in which case you should enter the revised objectives on your study plan so that you have a permanent reminder of what you are trying to achieve, when and why.

Distance-learning check-list

Prepare your study environment, your study tools and rules.

Undertake detailed self-assessment in terms of your ability as a learner.

Create a format for your study plan.

Consider your study objectives and tasks.

Create a study forecast.

Assess your study performance.

Re-evaluate your study forecast.

Be consistent when managing your study plan.

Use your Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) for tutorial support.

Make sure you keep in touch with those around you.

Tutorial Support

Programs

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. They are implemented over a sustainable period of time and professional support is consistently provided by qualified learning providers and specialist consultants.

Support available

You will have a designated Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and an Accredited Consultant and we encourage you to communicate with them as much as possible. In all cases tutorial support is provided online because we can then keep a record of all communications to ensure that tutorial support remains consistent. You would also be forwarding your work to the tutorial support unit for evaluation and assessment. You will receive individual feedback on all of the work that you undertake on a one-to-one basis, together with specific recommendations for anything that may need to be changed in order to achieve a pass with merit or a pass with distinction and you then have as many opportunities as you may need to re-submit project studies until they meet with the required standard. Consequently the only reason that you should really fail (CLP) is if you do not do the work. It makes no difference to us whether a student takes 12 months or 18 months to complete the program, what matters is that in all cases the same quality standard will have been achieved.

Support Process