Strategic Transformation – Workshop 1 (Framework Introduction)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Strategic Transformation is provided by Mr Remme Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

TO BE ADVISED

To request further information about Mr. Remme through Appleton Greene, please Click Here.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

The objective of organizational change management is to enable organization members and other stakeholders to adapt to a sponsor’s new vision, mission, and systems, as well as to identify sources of resistance to the changes and minimize resistance to them. Organizations are almost always in a state of change, whether the change is continuous or episodic. Change creates tension and strain in a sponsor’s social system that the sponsor must adapt to so that it can evolve. Transformational planning and organizational change is the coordinated management of change activities affecting users, as imposed by new or altered business processes, policies, or procedures and related systems implemented by the sponsor. The objectives are to effectively transfer knowledge and skills that enable users to adopt the sponsor’s new vision, mission, and systems and to identify and minimize sources of resistance to the sponsor’s changes.

Objectives

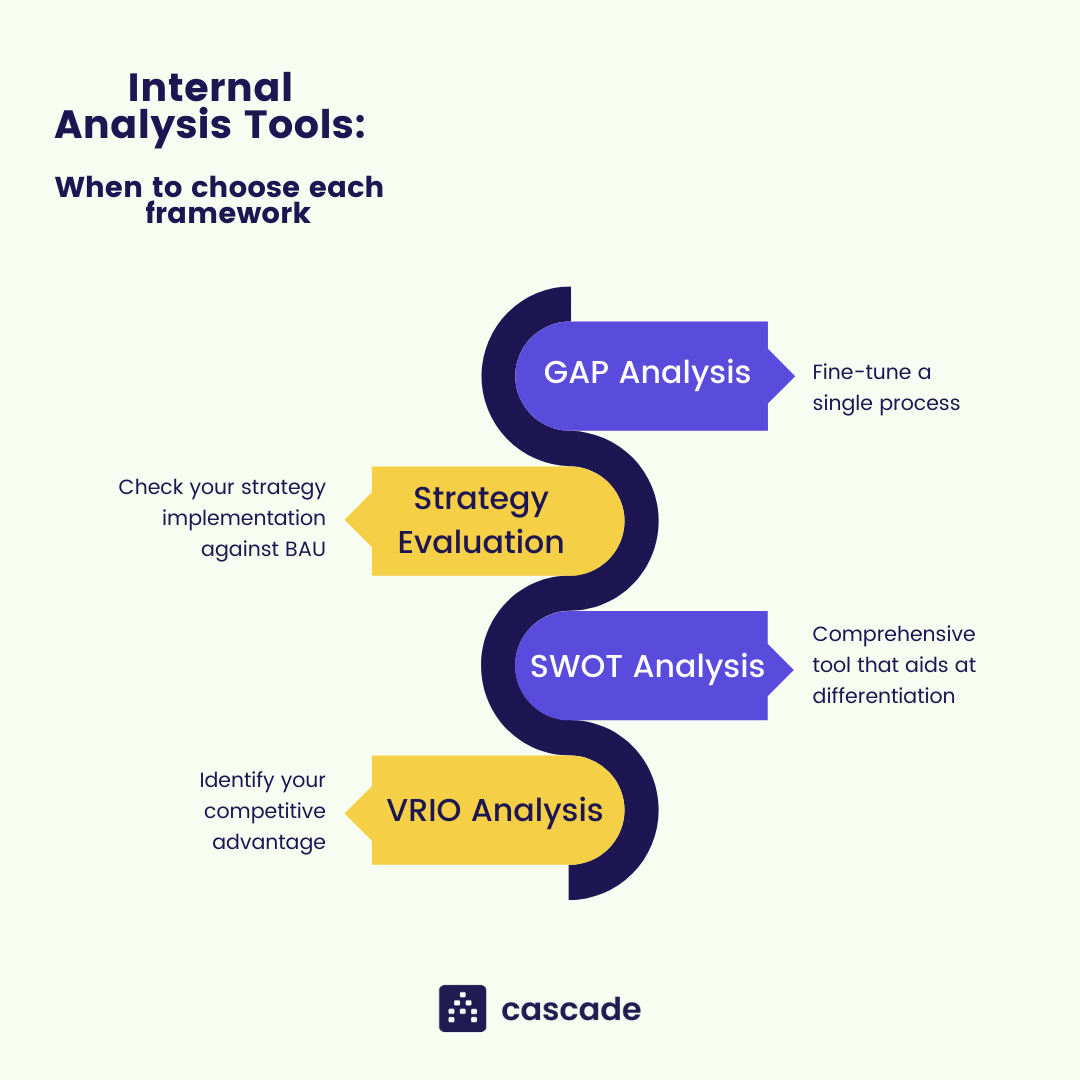

01. Breakthrough Value: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Strategic Analysis; departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Change Framework; departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Navigating Change; departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Transformation Strategies; departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Transitional Plan; departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. MBT Framework: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Best Practices: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Communication: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Employee-Centered: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Resistance: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Leadership & Stakeholders: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Breakthrough Value: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Strategic Analysis: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Change Framework: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Navigating Change: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Transformation Strategies: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Transitional Plan: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. MBT Framework: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Best Practices: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Communication: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Employee-Centered: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Resistance: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Leadership & Stakeholders: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

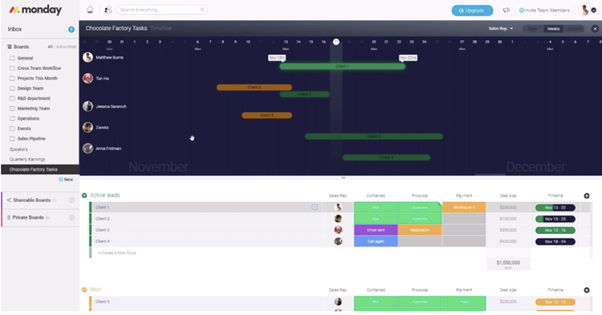

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Breakthrough Value.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Strategic Analysis.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Change Framework.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Navigating Change.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Transformation Strategies.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Transitional Plan.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse MBT Framework.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Best Practices.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Communication.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Employee-Centered.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Resistance.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Leadership & Stakeholders.

Introduction

Organizational Change And Transformation Planning

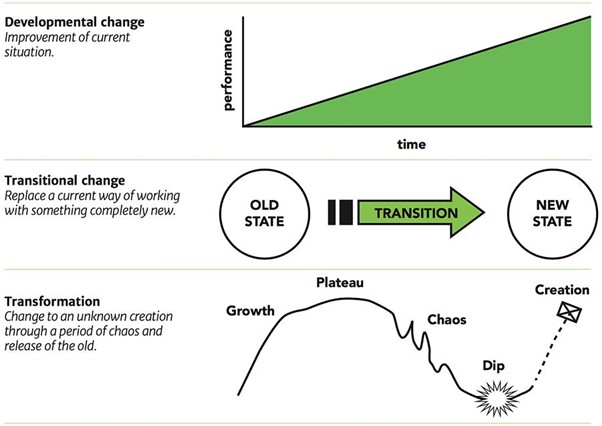

Definition: Transformation planning is the process of creating a [strategic] plan for changing an organization’s business processes by changing policies, procedures, and processes to shift it from a “as is” to a “to be” state.

Change Management is the process of gathering enterprise (or business) intelligence in order to perform transformation planning by assessing an organization’s people and cultures in order to determine how changes in business strategies, organizational design, organizational structures, processes, and technology systems will affect the enterprise.

Roles & Expectations: Leaders are expected to be able to assist in formulating the strategy and the plans for transforming a customer’s organization, structure, and processes, including support to that organization. They are expected to recommend interfaces and interactions with other organizations, lead change, collaborate, build consensus across the firm and other stakeholders for the transformation, and to assist in communicating the changes. To execute these roles and meet these expectations, leaders are expected to understand the complex, open-systems nature of how organizations change, and the importance of developing the workforce transformation strategies as a critical, fundamental, and essential activity in framing a project plan. They must understand the social processes and other factors (e.g., leadership, culture, structure, strategy, competencies, and psychological contracts) that affect the successful transformation of a complex organizational system.

Context

The objective of organizational change management is to enable organization members and other stakeholders to adapt to a sponsor’s new vision, mission, and systems, as well as to identify sources of resistance to the changes and minimize resistance to them. Organizations are almost always in a state of change, whether the change is continuous or episodic. Change creates tension and strain in a sponsor’s social system that the sponsor must adapt to so that it can evolve. Transformational planning and organizational change is the coordinated management of change activities affecting users, as imposed by new or altered business processes, policies, or procedures and related systems implemented by the sponsor. The objectives are to effectively transfer knowledge and skills that enable users to adopt the sponsor’s new vision, mission, and systems and to identify and minimize sources of resistance to the sponsor’s changes.

Best Practices and Lessons Learned

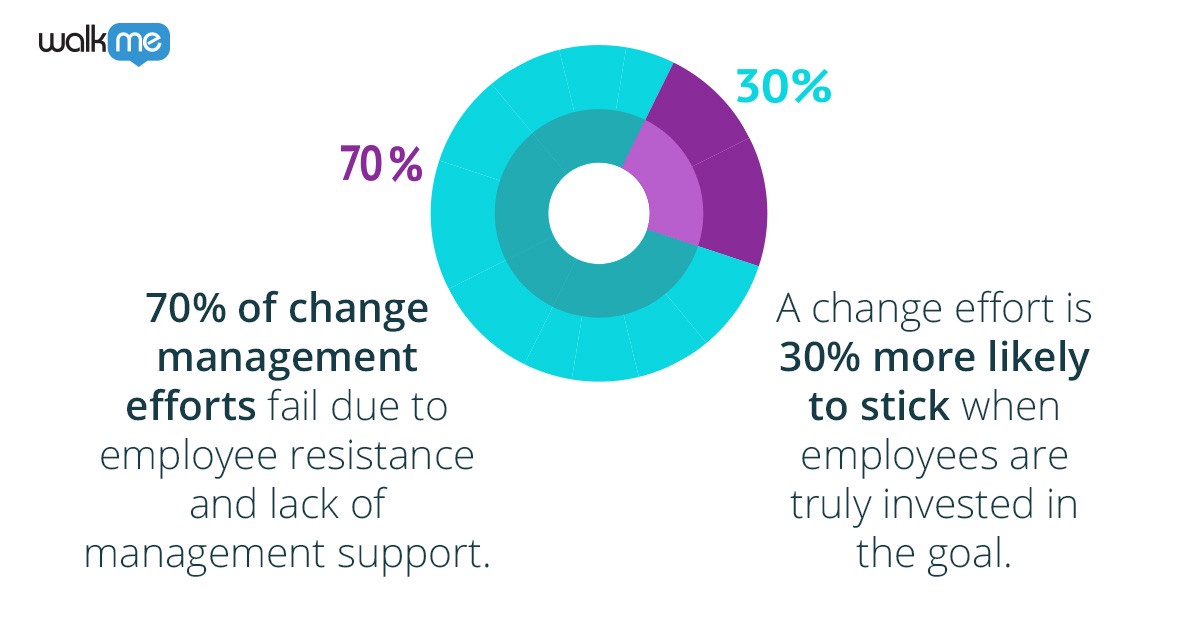

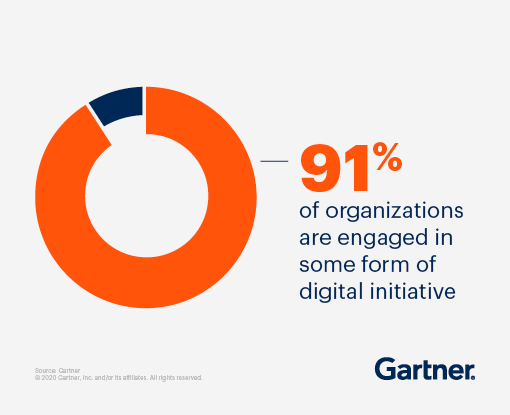

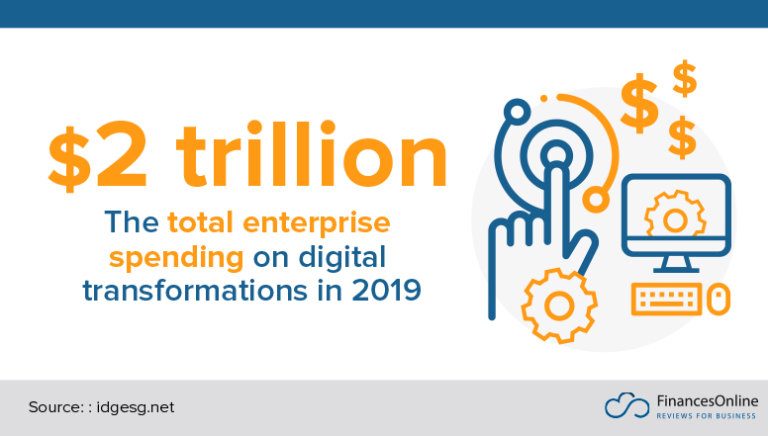

Implementation of a large-scale transformation project affects the entire organization. In a technology-based transformation project, an organization often focuses solely on acquiring and installing the right hardware and software. But the people who are going to use the new technologies—and the processes that will guide their use—are even more important. As critical as the new technologies may be, they are only tools for people to use in carrying out the agency’s work.

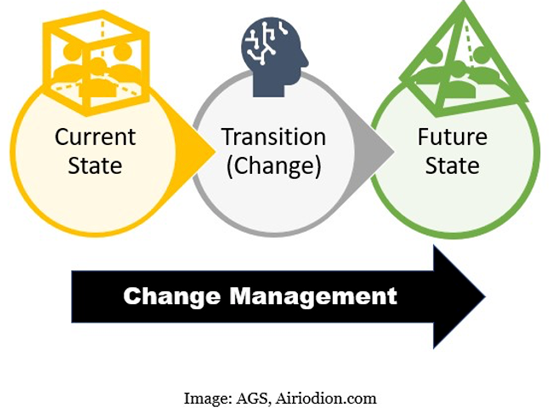

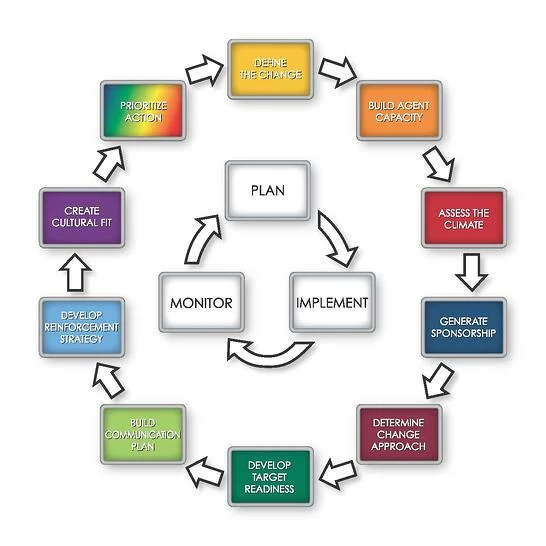

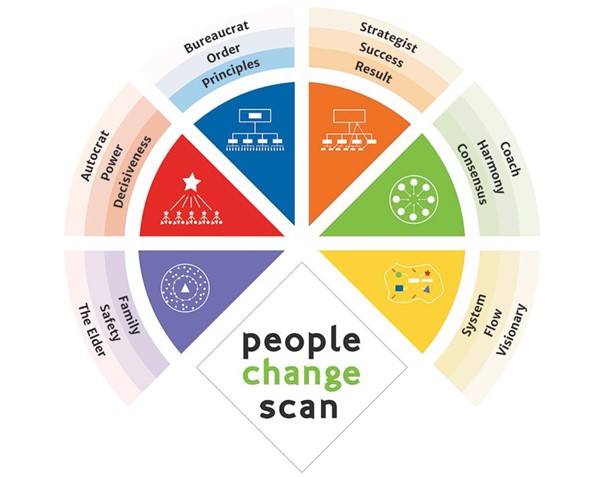

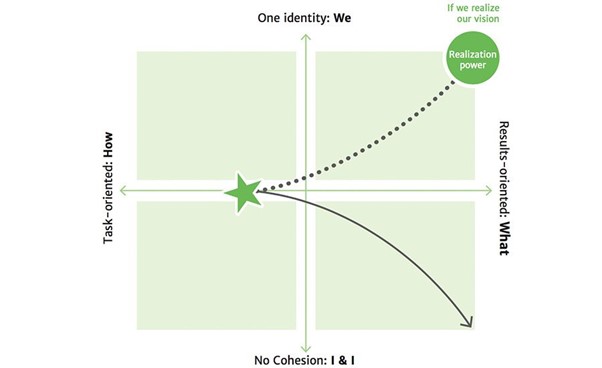

Figure 1. Organizational Transition Model

As shown in Figure 1, the discipline of organizational change management (OCM) is intended to help move an organization’s people, processes, and technology from the current “as is” state to a desired future “to be” state. To ensure effective, long-term, and sustainable results, there must be a transition during which the required changes are introduced, tested, understood, and accepted. People have to let go of existing behaviors and attitudes and move to new behaviors and attitudes that achieve and sustain the desired business outcomes. That is why OCM is a critical component of any enterprise transformation program: It provides a systematic approach that supports both the organization and the individuals within it as they plan, accept, implement, and transition from the present state to the future state.

Studies have found that the lack of effective OCM in an IT modernization project leads to a higher percentage of failure. According to a 2005 Gartner survey on “The User’s View of Why IT Projects Fail,” the findings pinned the failure in 31 percent of the cases on an OCM deficiency. This demonstrates the importance of integrating OCM principles into every aspect of an IT modernization or business transformation program.

Navigating the Change Process

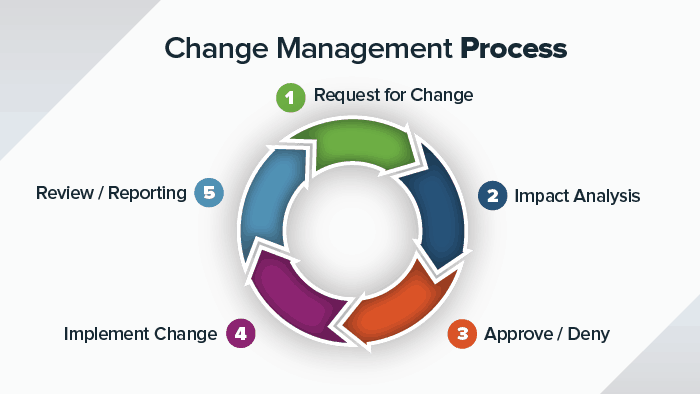

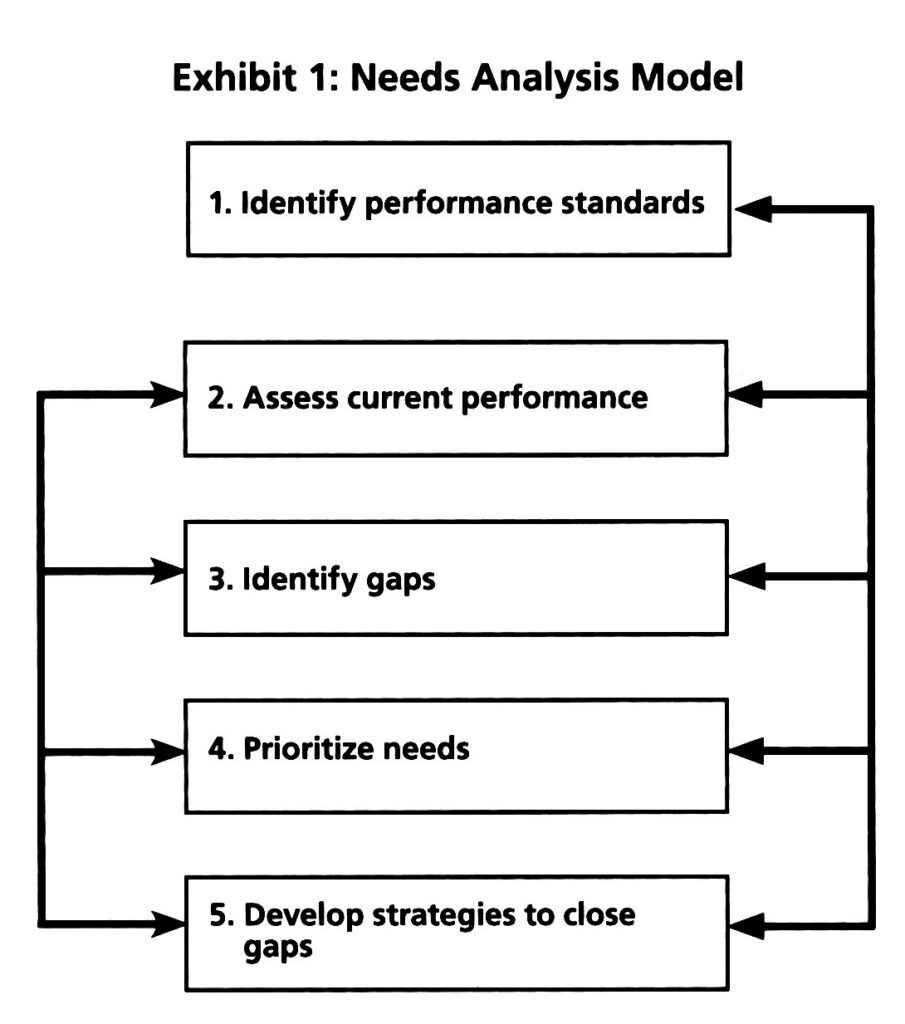

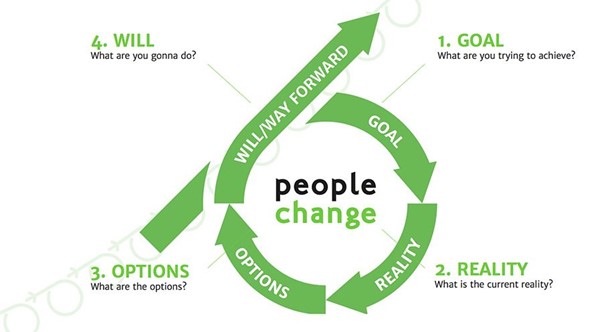

Organization leaders need to assess change as a process and work in partnership with our sponsors to develop appraisals and recommendations to identify and resolve complex organizational issues. The change process depicted in Figure 2 is designed to help assess where an organization is in the change process and to determine what it needs to do as it moves through the process.

Figure 2. An Organizational Change Process

By defining and completing a change process, an organization can better define and document the activities that must be managed during the transition phase. Moving through these stages will help ensure effective, long-term, and sustainable results. These stages unfold as an organization moves through the transition phase in which the required transformational changes are introduced, tested, understood, and accepted in a manner that enables individuals to let go of their existing behaviors and attitudes and develop any new skills needed to sustain desired business outcomes.

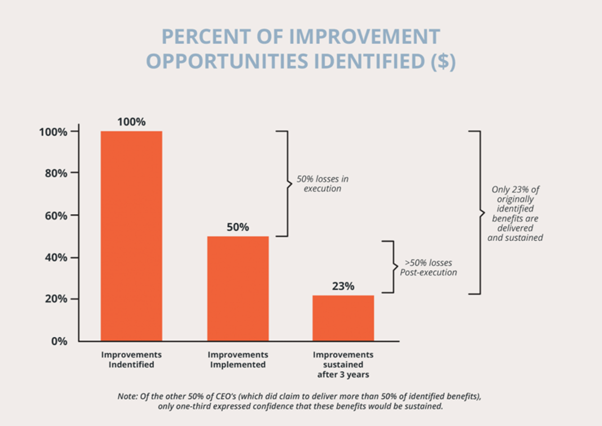

It is very common for organizations to lose focus or create new initiatives without ever completing the change process for a specific program or project. It is critical to the success of a transformation program that the organization recognizes this fact and is prepared to continue through the process and not lose focus as the organizational change initiative is implemented. Commitment to completing the change process is vital to a successful outcome.

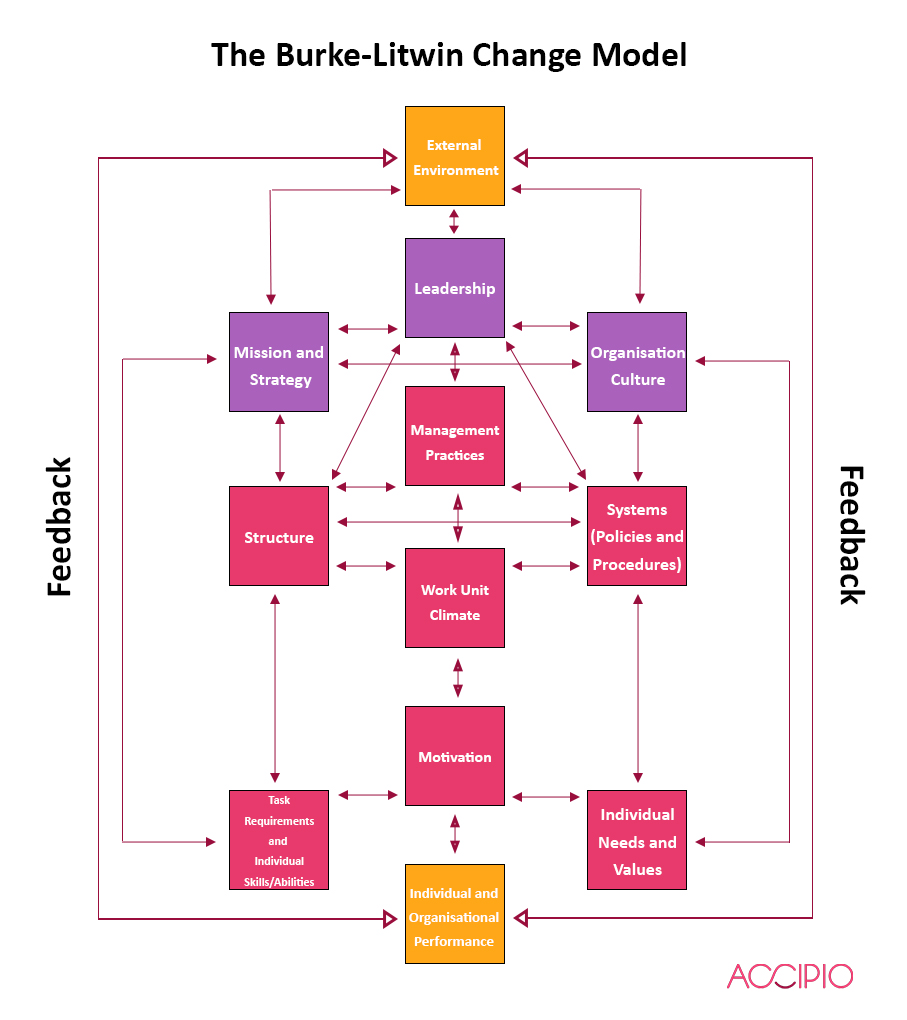

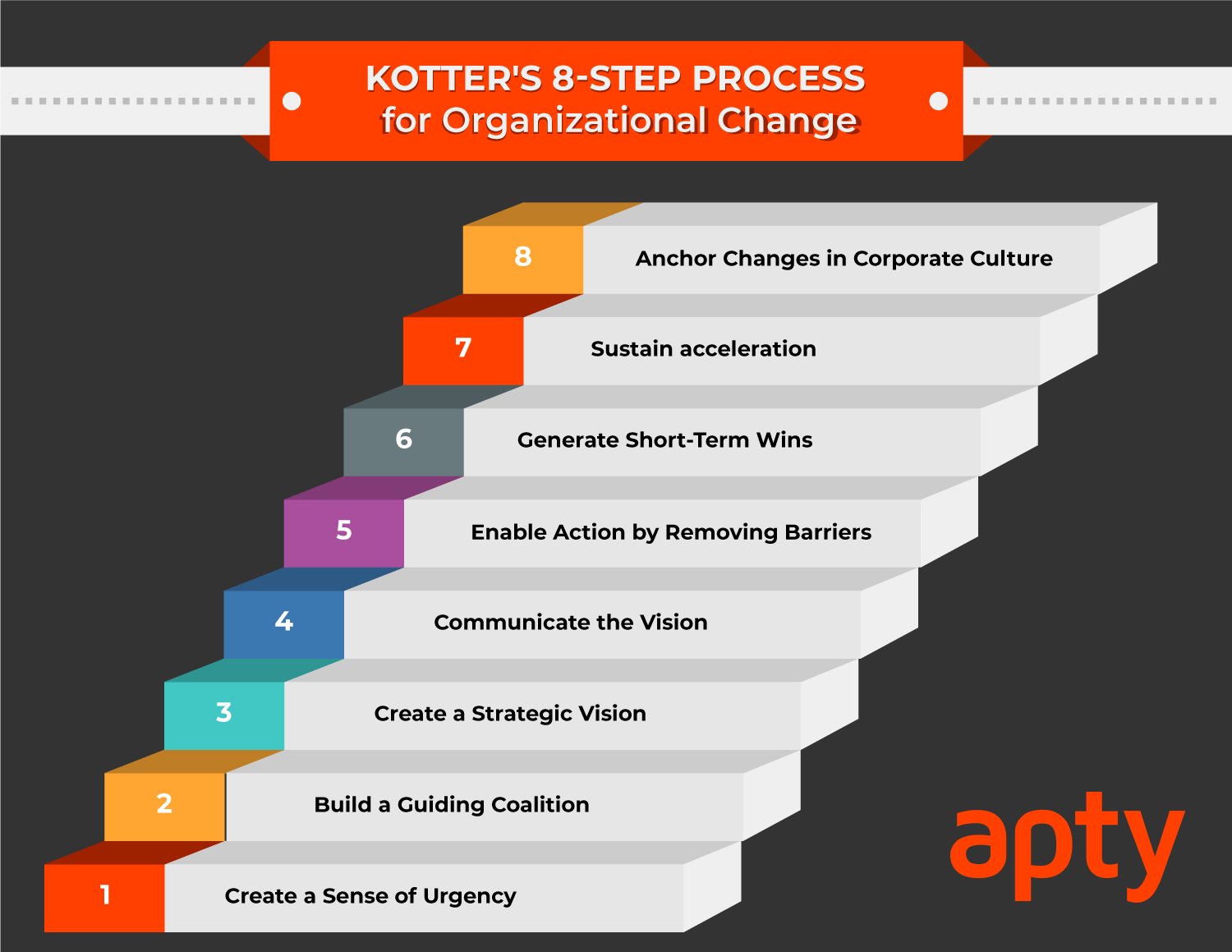

Framework for Change

In any enterprise transformation effort, there are a number of variables that exist simultaneously and affect the acceptance of change by an organization. These variables range from Congressional mandates to the organization’s culture and leadership to the attitude and behavior of the lowest-ranking employee. Social scientists use the Burke-Litwin Model of Organizational Performance and Change, or other approaches in line with the sponsor’s environment and culture, to assess readiness and plan to implement change. The Burke-Litwin Model identifies critical transformational and transactional factors that may impact the successful adoption of the planned change. In most government transformation efforts, the external environment (such as Congressional mandates), strategy, leadership, and culture can be the most powerful drivers for creating organizational change.

Transformation Strategies

Most organizations will ultimately follow one of three approaches to transformation. The type of approach is related to the culture and type of organization (e.g., loosely coupled [relaxed bureaucratic organizational cultures] or tightly coupled [strong bureaucratic organizational cultures]):

• Data-driven change strategies emphasize reasoning as a tactic for bringing about a change in a social system. Experts, either internal or external to the sponsor, are contracted to analyze the system with the goal of making it more efficient (leveling costs vs. benefits). Systems science theories are employed to view the social system from a wide-angle perspective and to account for inputs, outputs, and transformation processes.

The effectiveness of a sponsor’s data driven change strategy will be dependent upon (a) a well-researched analysis that the transformation is feasible, (b) a demonstration that illustrates how the transformation has been successful in similar situations, and (c) a clear description of the results of the transformation. People will adopt the transform when they understand the results of the transformation and the rationale behind it.

• Participative change strategies assume that change will occur if impacted units and individuals modify their perspective from old behavior patterns in favor of new behaviors and business/work practices. Participative change typically involves not just changes in rationales for action, but changes in the attitudes, values, skills, and percepts of the organization.

For this change strategy to be successful, it is dependent on all impacted organizational units and individuals participating both in the change (including system design, development, and implementation of the change) and their change “re-education.” The degree of success is dependent on the extent to which the organizational units, impacted users, and stakeholders are involved in the participative change transition plan.

• Compliance-based change strategies are based on the “leveraging” of power coming from the sponsor’s position within the organization to implement the change. The sponsor assumes that the unit or individual will change because they are dependent on those with authority. Typically, the change agent does not attempt to gain insight into possible resistance to the change and does not consult with impacted units or individuals. Change agents simply announce the change and specify what organizational units and impacted personnel must do to implement the change.

The effectiveness of a sponsor’s compliance-based change strategy is dependent on the discipline within the sponsor’s chain of command, processes, and culture and the capability of directly and indirectly impacted stakeholders to impact sponsor executives. Research demonstrates that compliance-based strategies are the least effective.

Regardless of the extent of the organizational change, it is critical that organizational impact and risk assessments be performed to allow sponsor executives to identify the resources necessary to successfully implement the change effort and to determine the impact of the change on the organization. Further information on change strategies and organizational assessments is found in the SEG article “Performing Organizational Assessments,” and in those listed above.

Leadership & Stakeholders

Leaders need to be cognizant of the distinction between sponsor executives, change agents/leaders, and stakeholders:

• Sponsor executives: Typically, sponsor executives are the individuals within an organization that are accountable to the government. Sponsor executives may or may not be change leaders.

• Change leaders: Typically, the change leader is the sponsor’s executive or committee of executives assigned to manage and implement the prescribed change. Change leaders must be empowered to make sponsor business process change decisions, to formulate and transmit the vision for the change, and to resolve resistance issues and concerns.

• Stakeholders: Typically, stakeholders are internal and external entities that may be directly (such as participants) or indirectly impacted by the change. A business unit’s dependence on a technology application to meet critical mission requirements is an example of a directly impacted stakeholder. An external (public/private, civil, or federal) entity’s dependence on a data interface without direct participation in the change is an example of an indirect stakeholder.

Note: Both directly and indirectly impacted stakeholders can be sources of resistance to a sponsor’s transformation plan.

Resistance

Resistance is a critical element of organizational change activities. Resistance may be a unifying organizational force that resolves the tension between conflicts that are occurring as the result of organizational change. Resistance feedback occurs in three dimensions:

• Cognitive resistance occurs as the unit or individual perceives how the change will affect its likelihood of voicing ideas about organizational change. Signals of cognitive resistance may include limited or no willingness to communicate about or participate in change activities (such as those involving planning, resources, or implementation).

• Emotional resistance occurs as the unit or individuals balance emotions during change. Emotions about change are entrenched in an organization’s values, beliefs, and symbols of culture. Emotional histories hinder change. Signals of emotional resistance include a low emotional commitment to change leading to inertia or a high emotional commitment leading to chaos.

• Behavior resistance is an integration of cognitive and emotional resistance that is manifested by less visible and more covert actions toward the organizational change. Signals of behavioral resistance are the development of rumors and other informal or routine forms of resistance by units or individuals.

Resistance is often seen as a negative force during transformation projects. However, properly understood, it is a positive and integrative force to be leveraged. It is the catalyst for resolving the converging and diverging currents between change leaders and respondents and creates agreement within an organizational system.

Creating the Organizational Transition Plan

As discussed in the beginning of this section (see Figure 1), successful support of individuals and organizations through a major transformation effort requires a transition from the current to the future state. Conducting an organizational assessment based on the Burke-Litwin Model provides strategic insights into the complexity of the impact of the change on the organization. Once the nature and the impact of the organizational transformation are understood, the transformation owner or champion will have the critical data needed to create an organizational transition plan.

Typically, the content or focus of the transition plan comes from the insights gained by conducting a “gap” analysis between the current state of the organization (based on the Burke-Litwin assessment) and the future state (defined through the strategy and vision for the transformation program). The transition plan should define how the organization will close the transformational and transactional gaps that are bound to occur during implementation of a transformation project. Change does not occur in a linear manner, but in a series of dynamic but predictable phases that require preparation and planning if they are to be navigated successfully. The transition plan provides the information and activities that allow the organization to manage this “non-linearity” in a timely manner.

It should be noted that large organizational change programs, which affect not only the headquarters location but also geographically dispersed sites, will require site-level transition plans. These plans take into account the specific needs and requirements of each site. Most importantly, they will help “mobilize” the organizational change team at the site and engage the local workforce and leaders in planning for the upcoming transition.

Strategic Organizational Change Communications

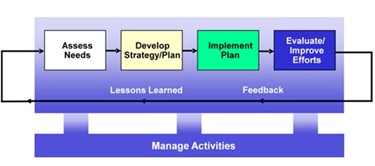

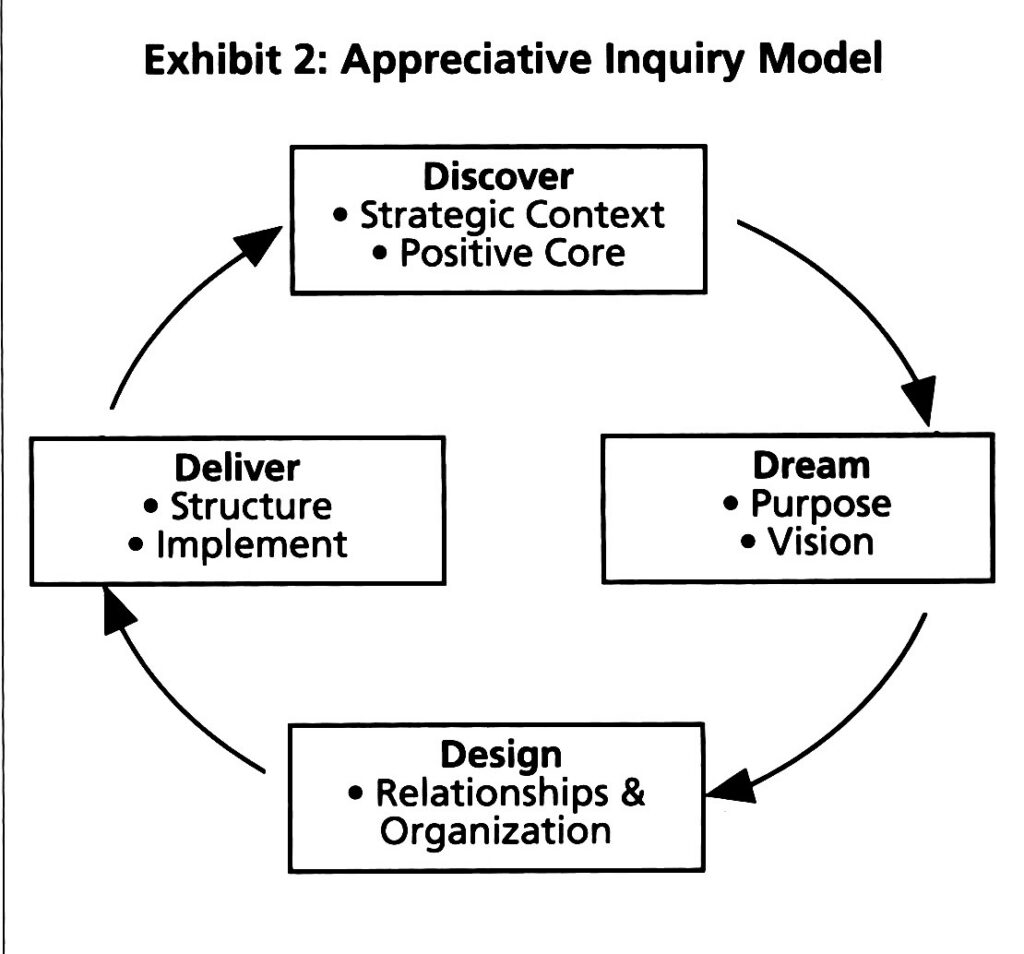

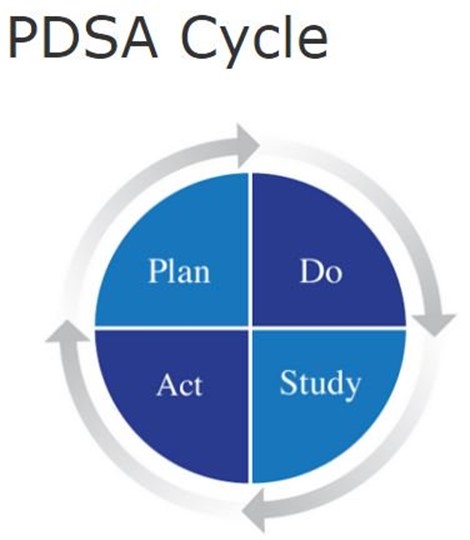

Figure 3. The Strategic Organizational Communications Process

A key component of the transition plan should address the strategic communications (see Figure 3) required to support the implementation of the transformation. Open and frequent communication is essential to effective change management. When impacted individuals receive the information (directly and indirectly) they need about the benefits and impact of the change, they will more readily accept and support it. The approach to communication planning needs to be integrated, multi-layered, and iterative.

Are You Certain You Have A Plan In Place?

Consider the following declarations of strategy gathered from genuine company documents and announcements:

“Our goal is to be the most cost-effective service.” “We’re pursuing a global approach”. “The company’s objective is to integrate a series of regional acquisitions”. “Unparalleled customer service is our strategy.” “Our strategy goal is to always be first to market.” “Our objective is to transition from defence to industrial applications,” .

What are the similarities and differences between these great declarations? The only difference is that none of them is a strategy. They are merely aspects of strategies, strategic strands. However, they are no more tactics than Dell Computer’s strategy of selling directly to customers, or Hannibal’s plan of crossing the Alps with elephants. And their use illustrates a growing trend: strategy fragmentation as a catchall term. Consultants and researchers have offered executives with a plethora of frameworks for understanding strategic problems after more than 30 years of rigorous thinking about strategy.

We now have five-forces analysis, core competencies, hypercompetition, a resource-based view of the organization, value chains, and a slew of other useful, if not always powerful, analytic tools.’ However, there has been little advice on what should be the end output of these tools—or what actually constitutes a plan. Indeed, the use of certain strategic instruments tends to lead to restricted, fragmented views of strategy, which correspond to the tools’ limited reach. Strategists who are drawn to Porter’s five-forces approach, for example, tend to think of strategy as a question of picking industries and sectors within them.

Executives who focus on “co-opetition” or other game-theoretic frameworks perceive their world as a series of decisions about how to interact with friends and foes. This issue of strategic fragmentation has gotten worse in recent years, as narrowly specialized academics and consultants have begun to practice strategy using their instruments. However, strategy is not the same as price. It isn’t a matter of capacity decisions. It is not responsible for determining R&D funding. These are strategy components that cannot be decided — or even considered — in isolation. Consider an aspiring painter who has been taught that the beauty of a painting is determined by its colors and hues. But, in reality, what can be done with such advice? After all, wonderful paintings necessitate much more than color selection: attention to shapes and figures, brush technique, and post-production processes. Above all, excellent paintings rely on the skillful integration of all of these aspects.

Some pairings are tried-and-true, while others are innovative and fresh. Many combinations, especially in avant-garde art, indicate disaster. Strategy has become a catchall term that can be used to imply anything. Regular portions of business journals are increasingly devoted to strategy, usually detailing how featured companies are coping with specific difficulties like customer service, joint ventures, branding, or e-commerce. Executives, in turn, discuss their “service plan,” “joint venture strategy,” “branding strategy,” or whatever other strategy is on their thoughts at the time. Executives then transmit these strategic threads to their enterprises, erroneously believing that this will assist managers in making difficult decisions.

However, how does understanding that their company is pursuing a “acquisition strategy” or a “first-mover strategy” assist the vast majority of managers in doing their jobs or setting priorities? How useful is it to have new initiatives publicized on a regular basis, with the word strategy thrown in for good measure? When executives refer to everything as a strategy and end up with a collection of strategies, they confuse the public and jeopardize their own credibility. They reveal, in particular, that they do not have a holistic view of the business. When executives refer to anything as a strategy, they create confusion and undercut their own credibility. Many readers of literature on the subject are aware that ‘strategy’ comes from the Greek ‘strategos’, which means “the art of the general.”

However, few people have given this essential origin much thought. What distinguishes the job of a general from that of a field commander, for example? Over time, the general is in charge of various units on multiple fronts and multiple conflicts. Orchestration and comprehensiveness are the general’s challenge—and the value-added of generalship. Great generals consider the big picture. They have a plan; it is made up of bits, or aspects, that come together to form a cohesive whole. Whether they are CEOs of established companies, division presidents, or entrepreneurs, business generals must have a strategy—a coherent, integrated, externally directed notion of how the company will achieve its goals.

Without a strategy, time and resources are easily wasted on ad hoc, unrelated operations; mid-level managers will fill the hole with their own, often parochial, interpretations of what the company should be doing; and the outcome will be a jumble of ineffective efforts. There are numerous examples of businesses that have suffered as a result of a lack of a cohesive strategy. Once a dominant power in the retail industry. Sears spent ten bleak years vacillating between a hard-goods and a soft-goods focus, dabbling in and out of ill-advised industries, unable to differentiate itself in any of them, and failing to develop a convincing economic logic.

Similarly, the formerly untouchable Xerox is attempting to resurrect itself, despite internal criticism that the corporation lacks a strategy. “I hear about asset sales, about refinancing, but I don’t hear anyone saying convincingly, ‘Here is your future.”- A strategy is a collection of choices, but it isn’t a catch-all for every essential decision an executive must make.

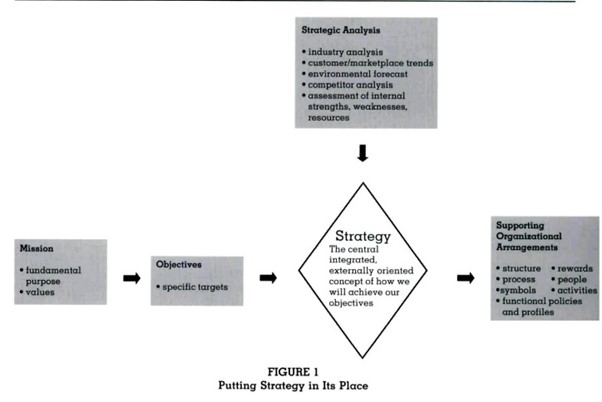

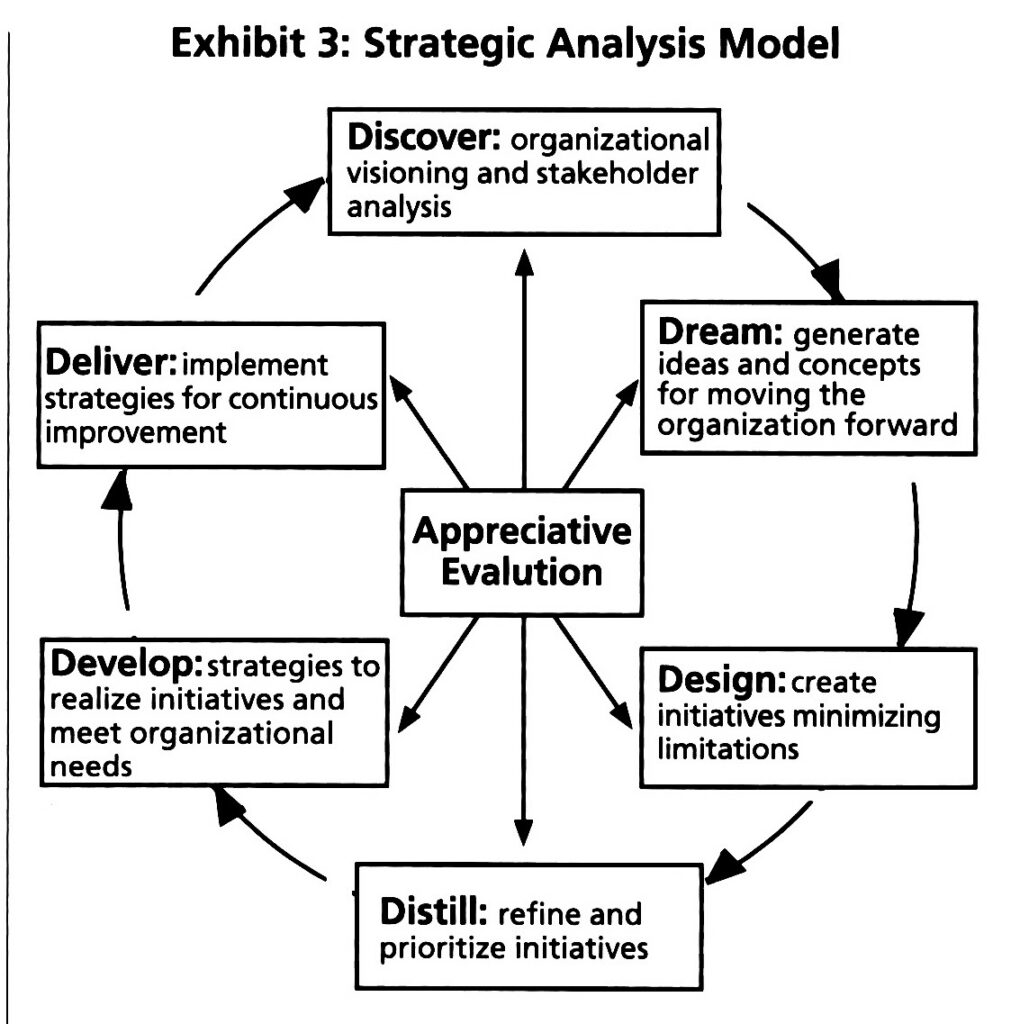

The company’s mission and objectives, for example, stand distinct from and govern strategy, as seen in Figure 1. As a result, we wouldn’t mention the New York Times’ dedication to being America’s newspaper of record as part of its strategy. GE’s strategy is driven by its goal of being number one or two in all of its markets, but it is not strategy in and of itself. A strategy would not include a goal of achieving a specific sales or earnings target. Similarly, while strategy is concerned with how a company intends to interact with its surroundings, internal organizational arrangements are not included. As a result, remuneration policies, information systems, and training programs should not be considered strategies. These are key decisions that should reinforce and support the strategy, but they do not constitute the strategy.

When everything significant is tossed into the strategy bucket, this crucial concept soon loses its meaning. We don’t want to portray strategy creation as a straightforward, sequential procedure. Figure 1 omits feedback arrows and other indicators that outstanding strategists think in repeating loops. The aim is to achieve a durable, reinforced consistency among the pieces of the strategy itself, rather than following a sequential approach.

The Building Blocks of Strategy

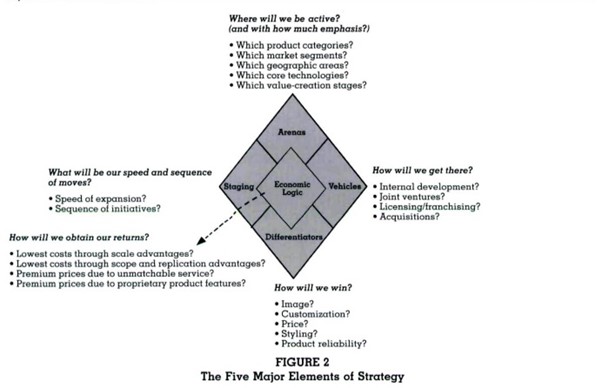

If a company must have a plan, that strategy must have components. What exactly are those components? A strategy, as shown in Figure 2, consists of five aspects that provide answers to real-world questions:

• Are there any arenas where we’ll be active?

• Transportation: how will we get there?

• Differentiators: What will make us stand out in the marketplace?

• Staging: What will our movement speed and sequence be?

• Logic of economics: how will we get our money back?

1. Arenas

The first question a company must answer on the Strategy Diamond is “where will we be active?” Organizations frequently make the mistake of being overly generic, such as when they state, “We want to be the number one consulting business.” However, rather than a strategy, this is a vision statement. To avoid falling into this trap, be as explicit as possible when describing arenas. You can do so by answering the questions below: Which product categories will we compete in?

• What channels are we going to use?

• Which market sectors are we going to focus on?

• Which geographical areas should we concentrate our efforts on?

• What essential technologies are we going to use?

• Which stages of value generation will we emphasize?

It is critical to underline the relevance of these domains when describing them. Assume your plan is to concentrate on a specific geography. You sell in other countries as well. However, you do so because it is logistically simple, and your fundamental goal is to concentrate on a single market.

2. Vehicles

Now that you know where you’ll be competing, you’ll need to figure out how you’ll get there. This is where we choose the vehicle that will take us from where we are to where we want to go. Here are some examples of responses:

• Partnerships

• Acquisitions

• Licensing

• Partnerships

• Franchising

• Create in-house

Once again, be as explicit as possible. Assume you’ve decided to branch out into a new product category. You should specify if you’ll purchase or construct this capacity in-house. Don’t make this decision on an ad-hoc basis. Instead, focus on developing a reasonable strategy. If you’ve only ever built in-house, then be honest, accept acquisition isn’t suitable for you.

3. Differentiators

What sets you apart from the competition? What are your products’ USPs (Unique Selling Propositions)? What is it about what you do that allows you to succeed in business?

Differentiation must be at the core of your plan. How can you win if you can’t find a method to set yourself apart? You can’t do it.

Differentiation can be done in a variety of ways, including:

• Price

• Quality

• Customization

• Reliability and Durability

• Time to market

• Time to upgrade products

• Customer service

It’s critical to identify your differentiators as soon as possible. This is due to the fact that differentiation does not arise by accident. If you want to provide the best customer service, you’ll have to invest time and money to do it. Similarly, if you want the best-designed goods, you’ll have to invest on that as well.

4. Staging

For a moment, let’s return to our general. A general does not move all forces on all fronts at the same time when fighting a war. Instead, some people go first, then others, and then still others. In business, staging is just as critical as it is in conflict. There are numerous examples of businesses that grew too quickly and before they were ready. The majority of these businesses are no longer in operation.

From one stage to the next, your plan must progress. You run the risk of getting ahead of yourself if you don’t. You run the risk of taking on more than you’re capable of. You’re in danger of going out of business.

During this step, ask yourself the following questions:

• What is the best sequence of steps to take?

• How quickly should we take these steps?

5. Economic Logic

The diamond’s last section brings everything together with one goal in mind: profit.

In a nutshell, this section is about deciding whether to compete on a low or high cost basis. Because you have economies of scale, you might be able to compete on price. Or because your replication costs are lower. Because you have a brilliant design or unique product features, you may be able to compete on price.

To demonstrate this, consider the following two examples of economic logic:

• Low-cost: Ryanair offers customers a cheaper cost per mile than any other European airline.

• Expensive: Apple may charge more because its customers are prepared to pay more for their distinctive design.

The five elements of the diamond must not only align, but also reinforce one another in order to have a solid plan. Let’s look at an example to help clarify this.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Breakthrough Value

Breakthrough Value Is Unlocked Through Business Transformation

Every company comes to a point where it’s time to make a change. As a leader, you are the one who stands at the crossroads and must make a decision. Should you increase your size? Or take a step to the side? Is it possible to create new products or services? Or do you want to keep laser-focused on your best-selling book? The decisions required for effective Business Transformation (BT) can be plagued with painful self-doubt, even for superstar entrepreneurs.

The first stage is to choose a problem to tackle, but after that, you’ll need a solid approach that will allow you to go forward while being flexible. Will you make blunders? Yes. However, proper Transformation planning can assist your small business in getting back on track after a setback.

Takeaways

• Leverage the power and potential of digital technologies—in particular, AI/machine learning, IoT, and robotics—to drive business transformation and create value

• Apply advanced Design-Thinking techniques to create breakthrough innovations

• Conceive new user experiences in areas where there is no prior solution to leverage

• Overcome organizational obstacles

Chapter 2: Strategic Analysis

Process Improvement Through Analysis

Identifying and resolving inefficiencies that waste resources and increase expense is the goal of process improvement. Analyses are conducted to establish which processes and process stages create value and which do not, as well as to determine how much non-value-adding activities may be decreased or eliminated. Using a planned strategy can help you get better results.

Methodologies for Strategic Planning

When management commits to using formal techniques, defining explicit goals, and offering employee training, process improvement initiatives will be more likely to succeed. Lean and Six Sigma are two popular approaches. Lean aims to continuously improve processes in order to increase efficiency. Six Sigma is a statistical control methodology that focuses on getting processes to an ideal level of statistical control. Employees must be properly guided and instructed in order to use any methodology effectively. To assure success, consulting services might be used.

Mapping Value Streams

Value Stream Mapping (VSM) gives you a snapshot of how things are right now. Before improvement efforts can begin to establish future-state expectations, it is important to understand current-state conditions. VSM is used by businesses to define all of the business, engineering, and manufacturing processes that go into delivering a finished product (or service) to a consumer. The value stream of the company is made up of several processes. The efficiency of each process has a direct relationship with profit levels.

VSM helps firms focus on each individual process and activity in the value stream by creating Value-Add vs. Non-Value-Add Process Maps. Assessing inputs, outputs, and process linkages can assist improvement teams in determining which activities contribute value and which do not. In the eyes of the customer, value-adding means that the activity adds to the item’s value. Non-value-adding signifies that it adds no direct value to the item but does affect the price customers must pay.

Waste

It’s possible that some non-value-adding operations will be required. Others may just contribute to resource waste. Toyota, which is widely regarded as a leader in continuous improvement, first implemented Lean principles in the early 1960s as part of a quest for increased efficiency. Toyota’s “Lean” strategy focused on removing waste from processes. The seven forms of waste, also referred to as fat, have been discovered. Overproduction, delay, unnecessary conveyance, over-processing, excess inventory, superfluous motion, and rectification are all things that improvement teams should be on the watch for.

Measure

Some method of measurement must be defined to permit a valid assessment of processes under present and future state conditions. What kind of evidence can be used to show whether a process is efficient or has been improved? Quantifiable process measures must be established. Numbers are objective and can inform management about whether or not goals have been met. The number of customer complaints received, the quantity of defective products produced, and the amount of time spent fixing mistakes are all instances of quantitative measures.

Chapter 3: Change Framework

Many businesses have undergone significant change in recent years, and the value of organizational culture in organizational analysis and change management is becoming increasingly apparent. Change implementation, on the other hand, is a difficult process that is not always successful for a variety of reasons.

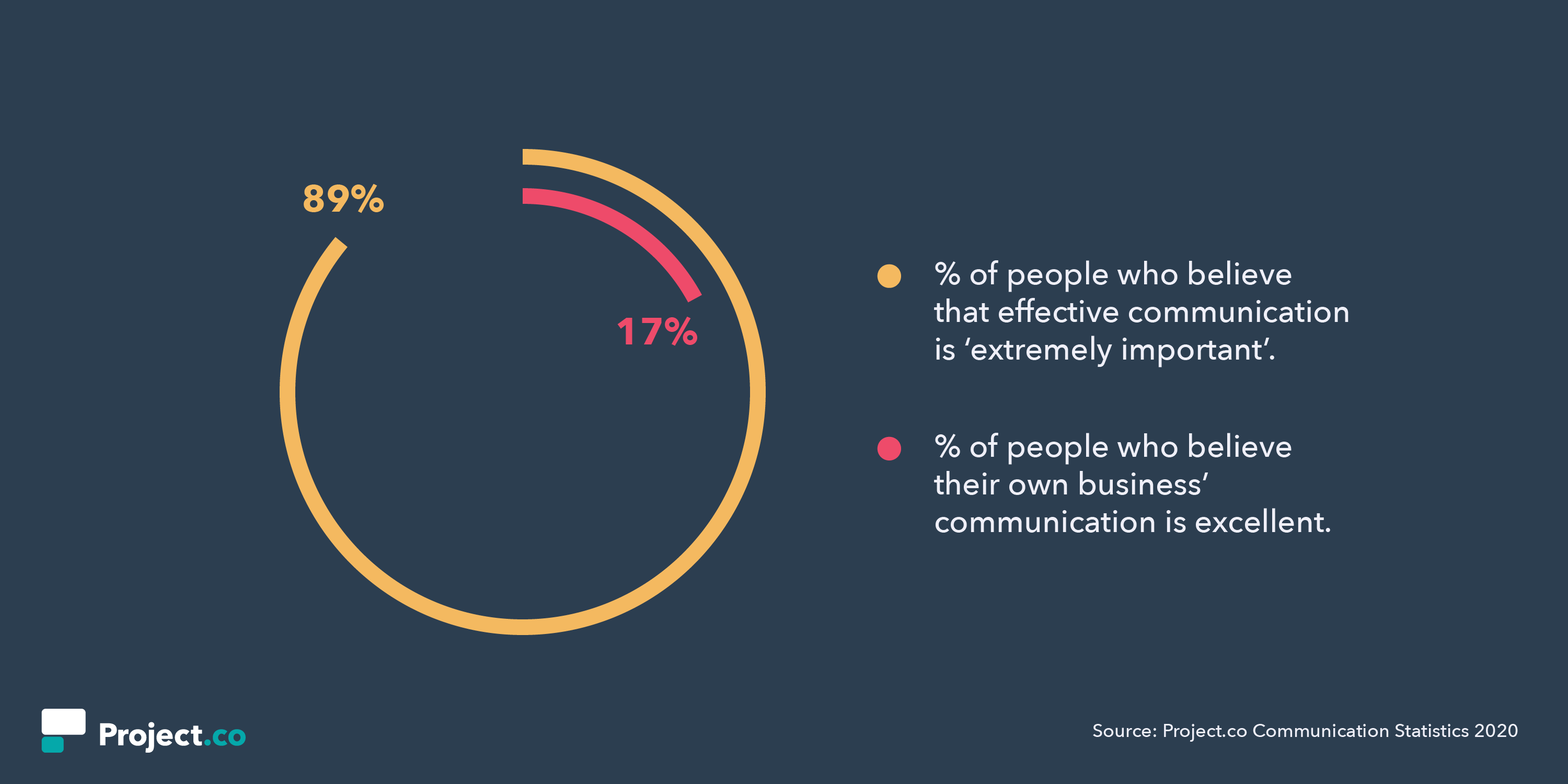

Poor communication and an underestimation of the amount of retraining required are at the root of most change failures. The major goal of this study is to determine the important actions that could help with change management. To build a theoretical foundation for the research, literature on organizational culture, the need for change, forms of change, and resistance to change was consulted.

Case studies and exploratory interviews on organizational change management were utilized to chronicle organizational change experiences and establish a strategic framework for change management. Acceptance and adoption of the designed method within a construction-based organization served as validation. The research has shown that well-planned change aids in the successful implementation of change. Not only is the development of more efficient and effective procedures important for successful change, but so is the alignment of corporate culture to support these new processes.

Chapter 4: Navigating Change

What Is Change Management And How Does It Work?

The actions a business takes to change or adjust a significant component of its organization are referred to as organizational change. this could encompass things like company culture, internal processes, underlying technology or infrastructure, corporate hierarchy, or something else.

Adaptive or transformational change can occur in an organization:

• Adaptive changes are tiny, incremental adjustments that a company makes over time to improve its products, processes, workflows, and strategies. Adaptive changes include hiring a new team member to meet rising demand or introducing a new work-from-home policy to attract more competent job applicants.

• Transformational changes are of a wider scale and scope, and they frequently imply a drastic and, at times, unexpected departure from the status quo. Transformational change might include the introduction of a new product or business division, as well as the decision to grow worldwide.

Transformation management is the process of directing organizational change from its inception and planning stages through implementation and resolution.

A set of starting conditions (point A) and a functional endpoint (point B) define change processes. The transition is a dynamic process that develops in stages. The major steps in the change management process are summarized here.

5 Steps In The Change Management Process

1. Get The Organization Ready For Change

An organization must be prepared both logistically and culturally in order to successfully pursue and implement change. Prior to going into logistics, cultural preparation is required.

During the planning phase, the manager focuses on assisting employees in recognizing and comprehending the need for change. They create awareness of the organization’s different challenges or problems, which operate as change agents and cause unhappiness with the status quo. Obtaining early buy-in from employees who will assist in the implementation of the change might help reduce friction and resistance later on.

2. Create A Vision And A Change Strategy

Managers must design a thorough and realistic plan for bringing about change once the organization is ready to embrace it. The strategy should include the following information:

• What strategic goals will this adjustment aid the organization in achieving?

• Key performance indicators: What will be used to assess success? What metrics must be shifted? What is the current state of affairs’ baseline?

• Project team and stakeholders: Who will be in charge of the task of change implementation? At each important point, who needs to sign off? Who will be in charge of the implementation?

• Project scope: What are the specific processes and actions that the project will entail? What isn’t included in the project’s scope?

Any unknowns or bottlenecks that may develop during the implementation process should be factored into the plan, which will necessitate agility and flexibility to overcome.

3. Changes Must Be Implemented

Following the procedures described in the plan to implement the desired change is all that remains after it has been created. The specifics of the program will determine whether or not modifications to the company’s structure, strategy, systems, procedures, employee habits, or other components are required.

Change managers must focus on empowering their workers to take the necessary measures to achieve the initiative’s goals during the implementation process. They should also try to anticipate bottlenecks and, once detected, prevent, remove, or reduce them. Throughout the implementation process, it is vital to communicate the organization’s vision to remind team members why change is being pursued.

4. Changes In Company Culture And Practices Should Be Embedded

Change managers must prevent a reversion to the previous state or status quo once the change endeavor is concluded. This is especially true when it comes to process, workflow, culture, and strategy changes within an organization. Employees may revert to the “old way” of doing things if they don’t have a strategy in place, especially during the transition time.

Backsliding is more difficult to achieve when reforms are embedded in the company’s culture and processes. Change management tools such as new organizational structures, controls, and reward systems should all be considered.

5. Analyze the Results and Evaluate the Progress

A change initiative’s completion does not imply that it was successful. A “project post mortem,” or analysis and assessment, can help company leaders determine whether a change initiative was a success, failure, or mixed result. It can also provide useful information and lessons that can be applied to future transformation attempts.

Ask yourself questions like, “Did the project’s objectives get met?” Is it possible to replicate this success elsewhere if it is? What went wrong if not?

Chapter 5: Transformation Strategies

If you’re in charge of a company, you’re undoubtedly considering drastic change. Your world is evolving due to new industrial platforms, geopolitical developments, global rivalry, and shifting consumer demand. You have upstart competitors encroaching on your firm with high valuations, as well as activist investors hunting for targets. Meanwhile, you have your own goals for your business: to be a profitable innovator, to exploit opportunities, to lead and dominate your market, to recruit highly motivated individuals, and to carve out a socially responsible role where your firm makes a difference. You should also get rid of any deadwood in your legacy system, such as procedures, structures, technologies, and cultural traditions that are holding your firm back.

A transformation program — a top-down restructure accompanied by cost-cutting across the board, a technical reboot, and some reengineering — is the traditional answer. Perhaps you’ve participated in a handful of these activities. If that’s the case, you’re well aware of how difficult it is for them to succeed. These initiatives are frequently late and over budget, leaving the company exhausted, demoralized, and little altered. They ignore the fundamentally new types of leverage accessible to firms in the recent decade: new networks, new data collection and analytical resources, and new means of codifying knowledge (see Miles Everson, John Sviokla, and Kelly Barnes’ “Leading a Bionic Transformation”).

Successful transformations are uncommon, but they do happen — and yours could be one of them. In this sense, a transformation is a significant change in an organization’s skills and identity that allows it to generate useful results that are relevant to its mission that it previously couldn’t achieve. It may or may not require a single large project, but the organization develops a continuing mastery of change in which executives and people feel comfortable adapting.

Changing economic times, as well as the increase of political and consumer turmoil, can put a company’s future in jeopardy. Consumers may start tightening their purse strings or switching to competitors’ products. In these cases, a company may choose to pursue a transformative strategy in order to position itself for long-term profitability.

Objectives

Transformational strategy is implementing major and drastic changes within a company to alter its short- and long-term viability. A change in course of action is usually necessitated by an external event, such as a downturn in the economy or the rise of a competitor, which forces the company’s owner and managers to reconsider their policies and processes. As a result, transformational strategy aims to increase revenue and market share, improve customer satisfaction and retention, and lower expenses in order to reinvest in other areas of the organization.

Tools

Enacting radical change inside a company necessitates the use of purposeful tools by the business owner and managers to ensure that the tactics they implement are useful and effective. Examining employee and management performance, evaluating financial data, redesigning technology and service programs, and refining project management plans are just a few of the tools available. A combination of tools and strategies is frequently used to help transform a business. A company losing market share to a competitor, for example, might change its customer service strategy, lower its price, and increase its marketing efforts.

Engagement of Stakeholders

Transformational strategy necessitates the involvement of the organization’s core personnel. The transformation process should include employees, board members, managers, and essential third parties such as vendors and core customers. Opening lines of communication between business owners and stakeholders can highlight flaws in the firm’s policies and procedures, as well as provide vital information into what needs to change within the company. Involving stakeholders in transformational strategy also helps to broaden and deepen the business’s resources and tools. The old adage “two heads are better than one” applies here: having additional individuals on board to strategize and implement solutions aids in the timely and effective transformation of the organization.

Setting Objectives

Setting goals and objectives is a crucial aspect of a transformational approach. Setting business transformation goals provides owners and management with a defined plan of action. Recognizing the need for change is the first stage, followed by agreement with stakeholders on the steps necessary to accomplish the change. This is frequently based on a vision for how the company should ideally look — should it broaden its market reach, strictly focus on a few items, or expand its public relations efforts into social media? Questions like this aid in the testing and implementation of improvements. Leadership must, above all, support the transformational strategy. Managers and business owners must regularly re-evaluate change plans to verify that they are on track to achieve the stated objectives.

Chapter 6: Transition Plan

A company’s ability to grow depends on its ability to welcome change. Change management, on the other hand, is one of the most difficult business ideas to grasp.

It is undervalued by businesses; changing employee attitudes and behaviors takes time. Others are unsure how to put a change management strategy into action.

Others are having trouble completely comprehending the business implications of changes; the company is dealing with something new, which is challenging.

With a few ideas and pointers, you’ll be prepared to take on change management in your firm.

All efforts and interim needs for implementing the new organization design are documented in the Organization Transition Plan. It serves as a central location for gathering, scheduling, and organizing all tasks related to the transition from the old to the new organization. The breadth and complexity of the change program will decide the overall approach – ‘big bang’ versus ‘phased’, for example. Communication, establishing and publishing new employment positions, and generating staff discussion guides that illustrate how responsibilities are evolving are all examples of typical tasks.

Chapter 7: MBT framework

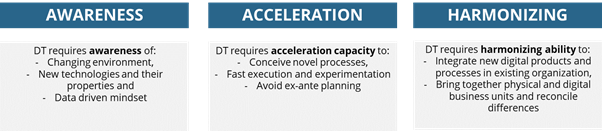

Let’s face it: when it comes to winning consulting business in the digital transformation arena, the big consulting firms have it easy. Their logo is visible on most doors and halfway up the procurement staircase. Few people doubt their credentials. However, a closer examination of most of their ‘digital transformation frameworks’ reveals that they are virtually identical to the traditional management consulting tools that they have used for the past 30 years. Old, subjective, analog, and unfit for the digital era.

Before company leaders will take Chief Digital Officers or smaller consulting firms seriously, they must demonstrate far more insight. They must generate new ideas that are relevant to the customer’s business.

But, before you start consulting, how do you generate new ideas?

The answer: data + frameworks.

When leveraging transformation pitching frameworks and platforms, it’s simple to come up with new ideas.

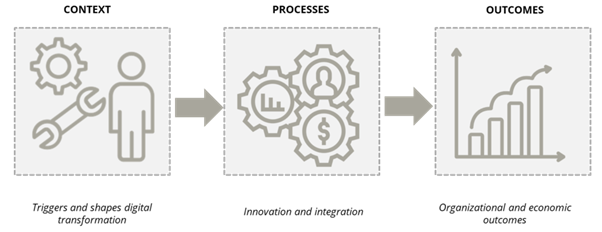

The digital footprint of a company can reveal a lot about it. Those who impact their sector produce a very distinct data footprint than those who participate passively over time as a business exposes its value proposition.

Measuring a company’s digital footprint is not the same as looking at its digital marketing. A company’s digital marketing may be excellent, yet its digital footprint may be lacking.

Innovators from all industries and government agencies have comparable data success characteristics over time. Those who are simply ‘doing digital’ fall behind the innovators. These qualities can be calculated by comparing them to industry peers and a market position. The ‘As-Is’ state is provided by this type of data.

This comparison of how a company or business unit performs versus competitors both within and outside their industry generates interesting insights and discussions.

Using modern transformation consulting platforms and frameworks can be a super-fast way to demonstrate strategic transformation competency and maturity. Even for customers you don’t know much about, you’re delivering insights from the start.

Chapter 8: Best practices

Framework for Formulating Organizational Transformation based on Best Practices and Lessons Learned:

Burke Litwin’s Organizational Performance and Change Model: Several variables affect the acceptability of change throughout an organization at the same time during an enterprise modernisation endeavor. The Burke-Litwin model (B-L) is a framework for determining the extent and complexity of various variables in a company. B-L provides a link between an assessment of the larger institutional context and the nature and process of change within an organization as a model of organizational change and performance. During organizational change, the B-L model identifies the following key factors to consider:

• Changes in the external environment drive “transformational” aspects within a company, such as mission and strategy, organizational culture, and leadership.

• Changes in the environment affect “transformational” factors within an organization, such as structure, systems, management practices, and organizational climate.

• Changes in transformational and transactional factors affect motivation, which affects individual and organizational performance.

Changes in transformational and transactional elements must be integrated and consistent for an enterprise modernization initiative to be effective and sustainable. The factors emphasized in the model, as well as the relationships between them, appear to be a good tool for communicating not only how organizations operate, but also how to effectively execute change, based on experience and practice. The SEG article “Performing Organizational Assessments” has more information on the Burke-Litwin model.

Organizational Transformation Strategy Parts: There are five important elements that make up an overall framework for change in an organization. In the transformation approach, each of these aspects is referred to as a ‘work stream,’ which is discussed in more detail later in this document. Leadership, communications, and stakeholder engagement, enterprise organizational alignment, education and training, and site-level workforce transfer are among the five pillars. The fifth work stream, site-level workforce transition, takes the preceding four aspects and applies them at the site or geographic region level to prepare and manage users in the field during the implementation process.

Chapter 9: Communication

Any business transformation project should be built on clear and constant communication from the start, between the project team, management at all levels, and the entire organization.

Effective communication keeps everyone informed and helps employees understand their individual tasks and the resources available to assist them achieve their objectives.

Furthermore, continual communication fosters a collaborative attitude, encourages employees to speak up, and ensures that everyone has the knowledge they need to handle any grievances, bottlenecks, or other difficulties that may arise.

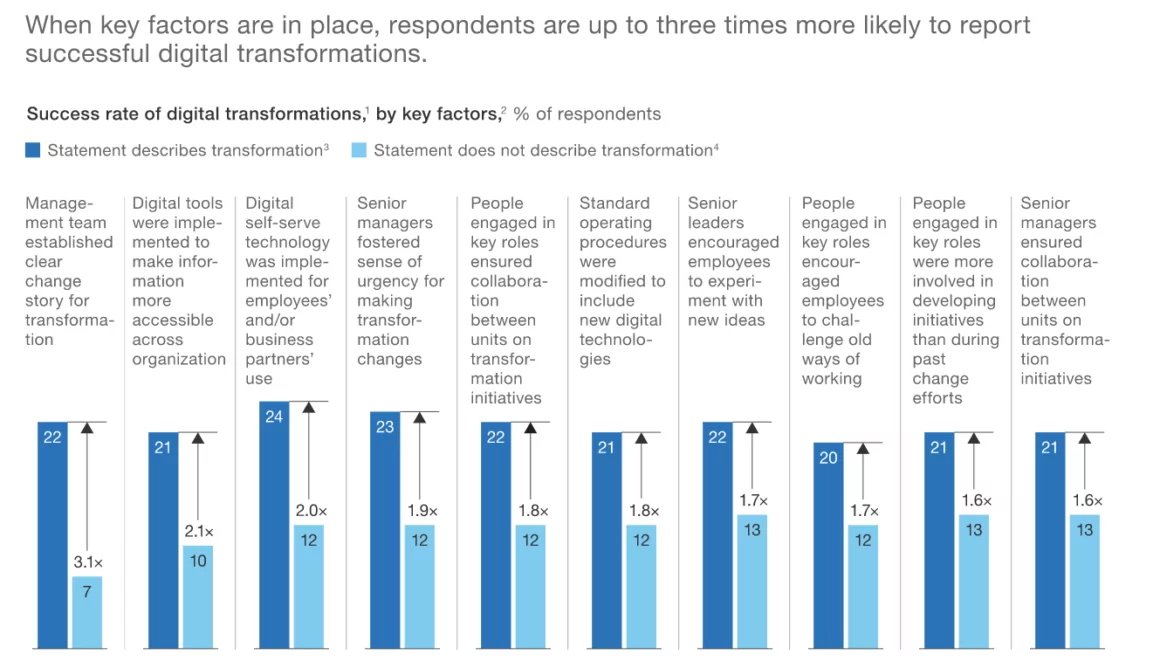

As a result, clear communication is essential during the company transformation process. Furthermore, statistics show that successful transformation is more than three times more likely in firms that implement this technique.

Choose the communication channels you’re going to use with caution.

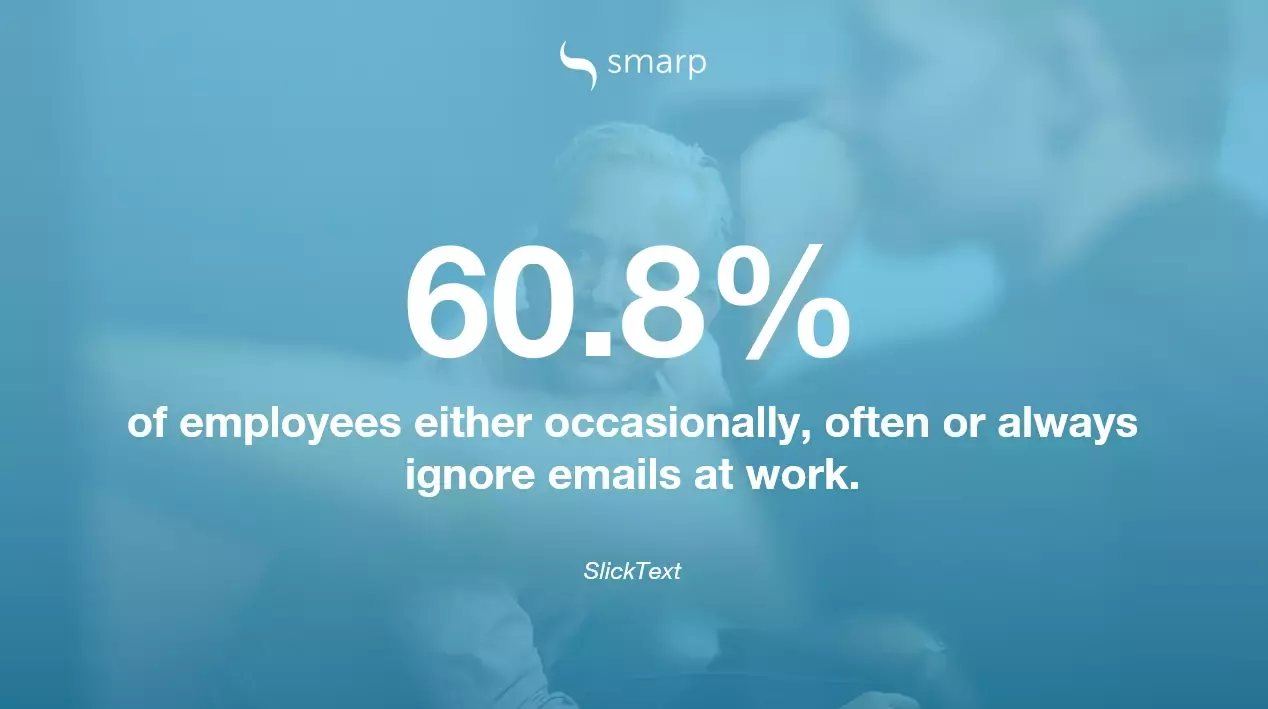

If you work for a large company, you’re presumably using a variety of internal communication channels. You name it: Slack, Microsoft Teams, email, intranets, document sharing, and project management software.

Within a company, there are many different ways to communicate. Because of the complexity of this communication ecosystem, ensuring that all workers receive the information they require to successfully implement new business transformation efforts is difficult.

Chapter 10: Employee-Centred

The 33-year average tenure of businesses on the S&P 500 in 1964 dropped to 24 years by 2016 and is predicted to decrease to just 12 years by 2027, according to a 2018 study on company longevity. What’s the bottom line? Over the next ten years, over half of the S&P 500 corporations will be replaced. How can you stay competitive in the face of so much disruption and change? You and your firm must learn to change quickly. In today’s digital world, how one changes effectively is determined by a number of elements, including the type of change required, your business model, and, most significantly, your workers. According to research, the success or failure of your company’s change efforts is determined by your employees’ experience with the change.

Employees should be at the forefront of your company’s digital transformation efforts. A patient-centered approach to care became a popular term in the healthcare business around a decade ago. The practice revolves around the patient and caters to their specific needs. It’s past time for companies to take a more holistic, employee-centric approach to their business models, particularly transformation models. Imagine your objectives as a wheel with spokes, with your employees in the hub and each spoke representing a different component of the change that will help you achieve your objectives.

• Worker Ecosystem

• Human Element

• Workforce Optimization

• Digital Dexterity

• Innovation and Growth

The Worker Ecosystem is evolving to include bots and artificial intelligence. Your ability to adapt will be determined by how you integrate this technology into your worker ecosystem. Analyzing your tasks properly will identify methods to use technology to assist you in your transformation. This is similar to providing patient portals in healthcare to encourage direct communication between the patient and the doctor without making an appointment. Even as AI becomes more common, the Human Element must never be forgotten. Humans give critical thinking, complexity, and empathy that technology cannot match. People must now be trained to evaluate, question, and explain the machine’s conclusions.

Chapter 11: Resistance

Change resistance is natural and to be expected. Employees are afraid of losing their employment, their relationships, and their activities. They don’t always believe that the change is worthwhile or that their boss knows what he or she is doing.

It’s critical to address change resistance. Managers can work against an employee’s instinct to reject change by cultivating a change-accepting atmosphere by developing trust and articulating the change clearly.

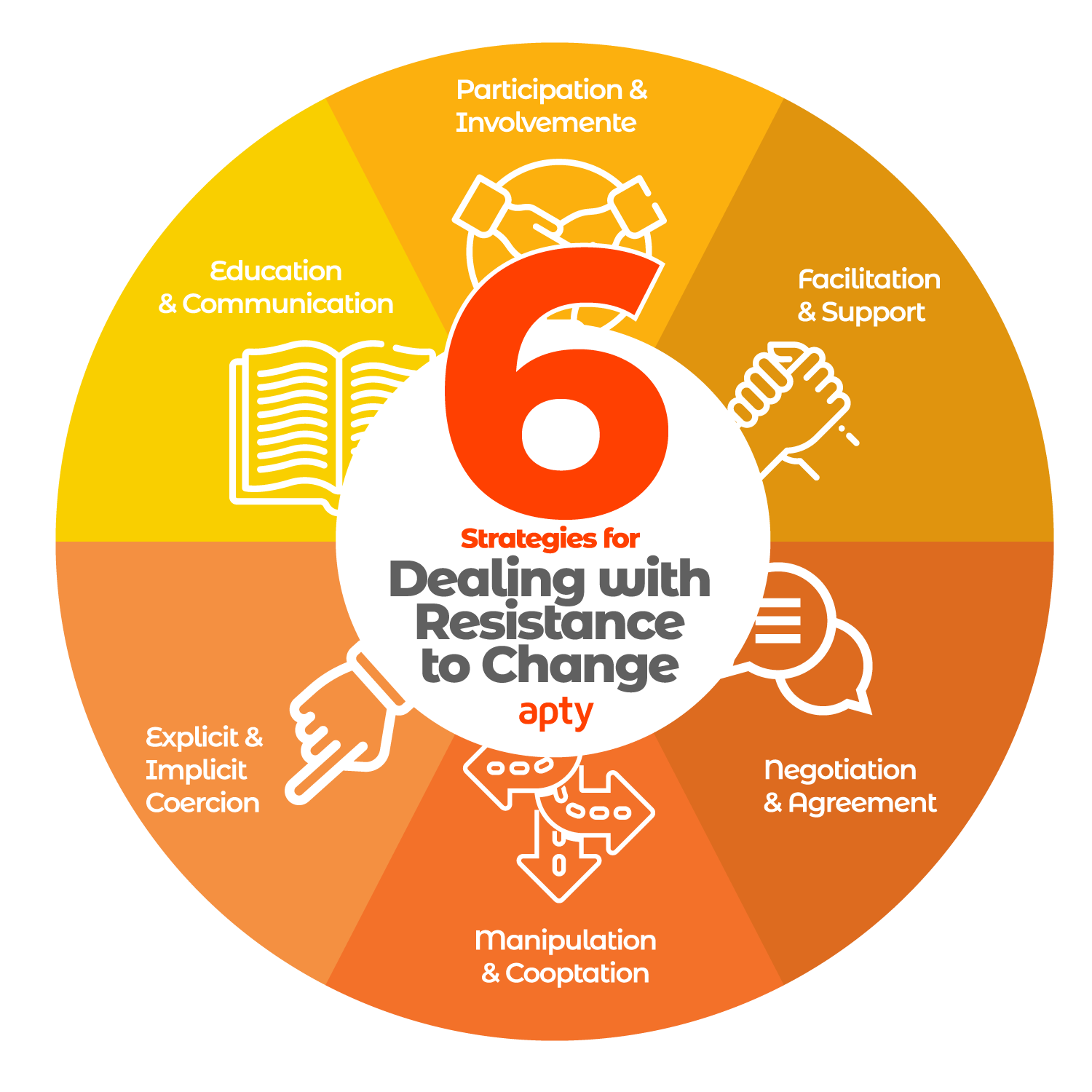

Dealing with Change Resistance: Strategies

You’ll need to execute particular measures to address employees’ concerns once you’ve identified probable causes of change resistance.

Companies must employ many techniques when it comes to adapting to contemporary technologies or overcoming opposition to change. The correct mix of Change Management Models and Tools is required for successful organizational change.

Four of the most common reasons for resistance are detailed below:

1. Fear and intolerance

Because they fear change, many employees oppose it. They are concerned that they will not have enough time to learn the new abilities and behaviors demanded of them, which makes them feel insecure.

They are also afraid of appearing inadequate in front of their coworkers due to a lack of time to adjust. Some relationships and activities may be lost as a result of the changes, while others may be established.

If a person’s tolerance for change is low, they may actively fight change for reasons they don’t understand, which are frequently rooted in fear of failure.

2. Self-interest

Some people may believe that if they change, they will lose power, whether it is substantial decision-making authority or the ability to influence their team. Others may interpret one change as a hint that more changes are on the way, which they may regard as a threat.

If someone perceives that a change will jeopardize their career, they are more inclined to fight it. Any endeavor that they view as posing a threat to their current circumstances will be met with resistance.

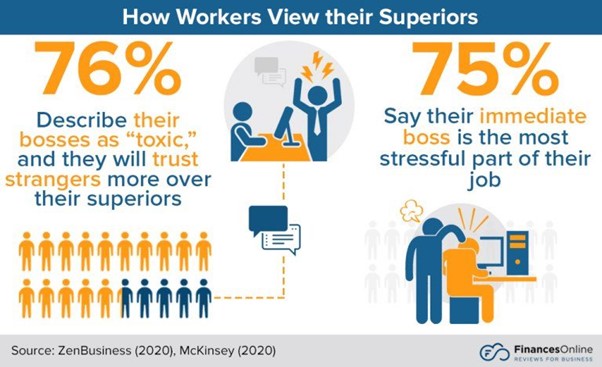

3. Lack of trust

Staff are more likely to oppose change if there is already a lack of trust between the management and his or her employees. While establishing a high level of trust between employees and supervisors is tough, managers must attempt to improve these relationships.

Misunderstandings arise as a result of a lack of trust, and employees are less likely to “buy in” to necessary adjustments. Managers must rapidly dispel any misconceptions in order to prevent opposition from spreading throughout a company.

4. Ineffective communication

The manner in which the change is communicated to staff is critical. Other affected employees will certainly reject if a change isn’t shared in its totality, or if it’s just communicated to a small group of people. Employees’ reactions are determined by how the change is communicated.

Resistance should be expected if a manager cannot define the process of changing exactly what needs to be changed, how the changes will be done, and how the change will better things.

Chapter 12: Leadership & Stakeholders

7 strategies for gaining leadership support for process improvement

Leaders are the catalysts for change. It could spell the difference between success and failure for your company if your leadership team leads the drive on process improvement.

Executives who are on board can help foster a positive process management culture by exhibiting their belief in the organization’s benefits and making it clear that they expect teams across the organization to do the same.

They also have the authority to make strategic and resourcing decisions on process improvement training and implementation.

1. Assisting leaders in improving procedures

Executive teams will have a lot of initiatives vying for their time, attention, and resources. Be specific about why your initiatives merit executive attention and support while making your case for process improvement.

There are five strategies to enlist the support of your executive team in your process improvement efforts:

2. Get a sense of what’s happened previously.

Begin by going over the reasons why the company decided to go on a process improvement journey in the first place. Make a list of concerns they’d like to solve, and then explain how process improvement may help. If any of the original organizers are still around, ask them what they planned to accomplish.

Look at the current strategic priorities that business teams are focusing on if the initial team that kicked off the process improvement journey is no longer with the organization. You might take use of this chance to demonstrate how a more effective process improvement approach can aid in aligning teams with the strategy and supporting initiatives, as well as how exec support can help to successfully embed change.

Consider what the organization wants to accomplish and how you may contribute to these goals. How can you achieve your goal, for example, if teams are unclear about what is required of them on a daily basis? Maybe your processes differ depending on where your offices are located, and there’s a lot of uncertainty about who does what – how can everyone use a single source of truth to improve cohesion and effectiveness?

3. Find out what’s important to them.

Knowing what business topics your executives are passionate about will help you make better decisions. Target the issues that they are passionate about, rather than the subjects that other executives on the leadership team are passionate about.

Have a sense of what your organization’s priorities are and what they consider to be vital before approaching a specific sponsor. Your HR director may be preoccupied with managing a legislation for teams dispersed across locations and regions. Your head of operations may be most concerned with risk management, but your director of customer success may see a platform that standardizes service levels and results in satisfied customers.

4. Draw attention to potential roadblocks.

People are generally more driven by a desire to avoid pain than by a desire to win. Raising awareness of potential stumbling blocks that your executive teams should avoid is a surefire method to capture their attention.

You’ll have a better chance of persuading your bosses to join you if you can spot problems and propose a solution. Take your discoveries to the next level. Exaggerate the issue, quantify it, and explain why it could be harmful to the company. Then demonstrate how process management, in conjunction with an improvement culture, may assist.

Another option is to focus your investigations and begin with a certain team or job rather than the entire company. For example, you may begin by approaching the CEO or the HR director.

5. Create a comprehensive image.

Gather facts to explain the impact and cost of poor process management rather than merely asking your senior executives for buy-in. Find ways to communicate the complete story about what process improvement can do for your business teams on a daily basis, and back up your assertions with data.

When discussing the software that supports your organization’s continuous improvement activities, avoid being ambiguous. Make the benefits of your platform tangible by emphasizing them. Use comments like: ‘By making processes accessible, encouraging process evaluations, and providing an easy feedback mechanism, our intuitive BPM software engages entire teams in continuous development.’

Request case studies from your software provider that show how their clients have benefited from using business process management software. Personal testimonials, client recommendations, and statistics to demonstrate efficiency benefits could be used as examples.

6. Sell the possibility of leaving a legacy.

Many leaders are enthusiastic about their work and want to leave a lasting impression on their company.

Implementing a process improvement culture can have a significant impact on business teams and an organization’s success. With the help of engaged teams that are executing processes that are aligned with the business goal, executives are well-positioned to leave a legacy.

7. Begin the discussion.

Speak in a way that your executive team understands. You can start a conversation that piques their interest and keeps their attention by knowing their pain spots and hobbies. Share stories with the proper people about how inadequate processes are impeding the organization and its teams.

Getting commitment from your leadership team to support meaningful process improvement isn’t about navigating a corporate structure – it’s about people, regardless of whether your organization’s vocabulary includes terms like business process management, workflow, process improvement, or continuous improvement.

Curriculum

Strategic Transformation – Workshop 1 – Framework Introduction

- Breakthrough Value

- Strategic Analysis

- Change Framework

- Navigating Change

- Transformation Strategies

- Transitional Plan

- MBT Framework

- Best Practices

- Communication

- Employee-Centered

- Resistance

- Leadership & Stakeholders

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Strategic Transformation corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast