Strategic Decision Making – Workshop 1 (Understanding how we think)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Strategic Decision Making is provided by Mr Albina MBA BA Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Mr Albina is the Founder & Director of Quintessential Consulting Pty Ltd. He established Quintessential in 2013 to help business leaders make more informed, and effective decisions in the rapidly increasingly complex. He accomplishes this by creating resilient workforces and future-proofing their people to the increasing uncertainties of today’s complex environment, helping them to become more agile, adaptable, and less reliant on certainty.

With more than 30 years of experience in Government, Industry and Small to Medium Business, Mr Albina blends his working knowledge with the latest thinking in contemporary leadership and management methodologies. As an Executive Coach, Consultant and Corporate Educator, Mr Albina utilises Systems Thinking approaches to enable leaders, managers and team members to unlock their potential through a mind-set shift, which makes it possible to operate effectively in the grey space of decision-making. By disrupting conventional patterns of thinking, Mr Albina coaches his clients to see and act in different ways, revealing new possibilities that are otherwise unavailable in the status quo.

Mr Albina believes, “We need different ways to do things as the complexity of today’s workplace is becoming increasingly stressful, with managers struggling to keep up with the rate of change, rapidly evolving technology, the management of multiple stakeholders as well as ambiguous lines of accountability.“

Starting his career as an Aerospace Engineer, Mr Albina has worked internationally for some of the world’s leading Aerospace and Defence Industry organisations, including Airbus, Boeing, Defence Industry and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). His considerable management knowledge, engineering expertise and cross-industry experience is much sought after and has seen him appointed to oversee strategic change, operational integration and reform for Defence, Government, Resources, Utilities, Telecommunications, Sports & Recreation and more recently, the development of First Nations ‘on-country’ initiatives involving environmental resilience, youth justice and business sustainability.

A graduate of the Australian Defence Force Academy, Mr Albina completed his undergraduate degree at the University of Sydney in 1993 where he was awarded a Bachelor Engineering majoring in Aeronautical Engineering. He has since gone on to further studies including a Masters Degree in Aerospace from the University of New South Wales in 1999; a Graduate Diploma in Test & Evaluation from the University of South Australia in 2003; and an Executive MBA in Complexity Leadership & Management from Queensland University of Technology in 2013.

He is a Sessional Academic and an Executive Coach for the Queensland University of Technology’s Graduate School of Business and Chairman of the Board for an NDIS organisation in Brisbane.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

The first workshop, ‘Understanding how we think’, is designed to help the participants to identify and unpack the way we understand, make sense, comprehend, and make meaning of the things that we encounter. Understanding how we think involves delving into various facets of cognitive processes, including how we process information, how we make decisions, and how we solve problems. By understanding these aspects, we gain insight into the complexities of human thought, which can lead to better understanding of how we make decisions, how we problem-solve, and how we critique the interactions around us. Ultimately, it also fosters empathy and better communication, as we appreciate the diversity in how people think and perceive the world.

“When we can make sense of things in different ways, new behaviours and practices can be created, which reveals new and novel possibilities and opportunities.”

During this first workshop, we will establish a foundational understanding of what it means to think, so that we can subsequently develop our skills in strategic decision making, knowing when, what, how and why it is necessary. We will define your learning agenda through a structured learning process and, utilise a personal journal to help develop your strategic decision-making skills.

Objectives

01. Complex times – new mindsets. Exploring and understanding how we think by interpreting and making sense of the world around us, leading to the decisions that we make.

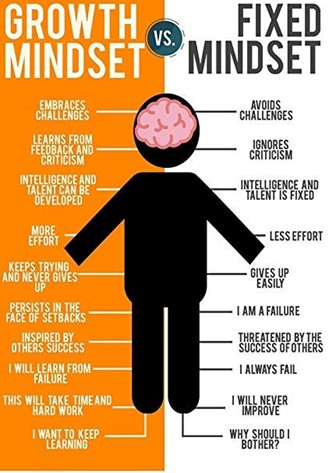

02. Understanding our mindset. Understanding our mindset, and how to create healthy spaces, both physically and socially, to foster more effective thinking.

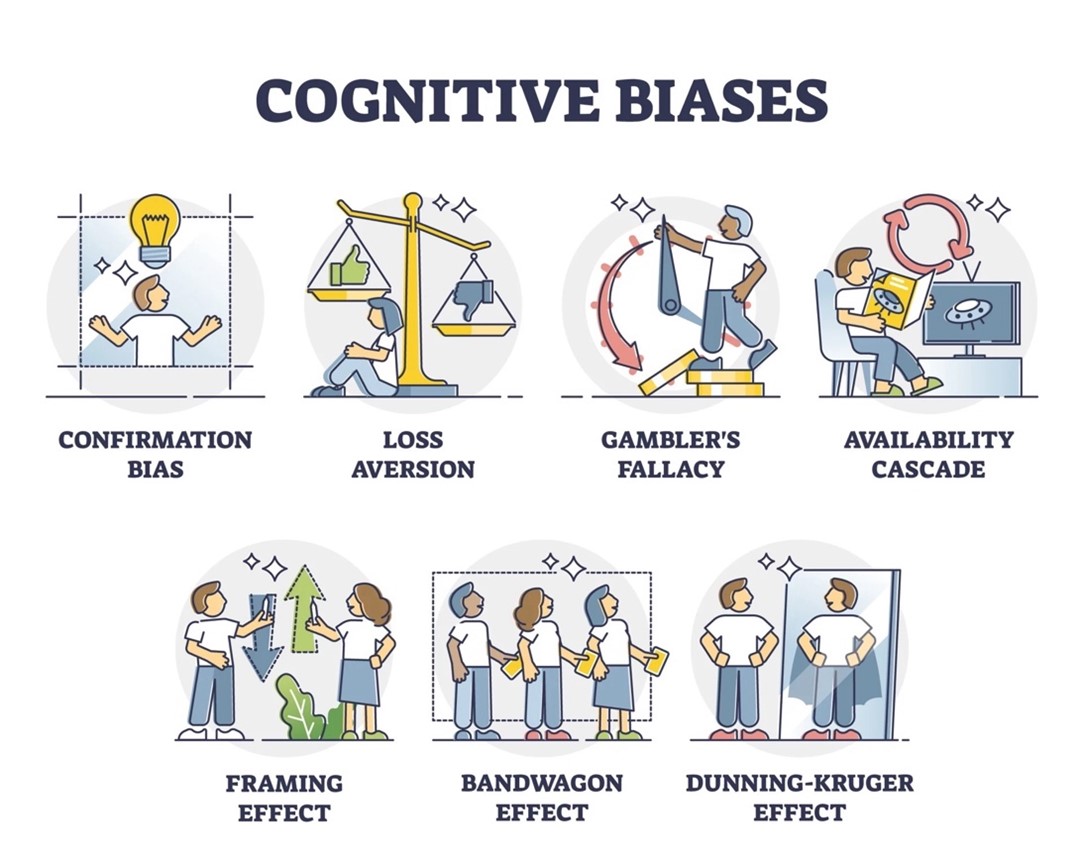

03. Biases & Heuristics. Understanding the factors that may lead us to make flawed judgments and irrational decisions, and that impacts our ability to make sense of things in a balanced and rational manner.

04. Our Thinking Audit. Intentionally stopping to reflect and invest time to better understand our thinking preferences and cognitive styles, and the way we go about sense-making, solving problems, and creating solutions.

05. Personal Mastery. Intentionally defining a self-directed pathway towards our strategic goals.

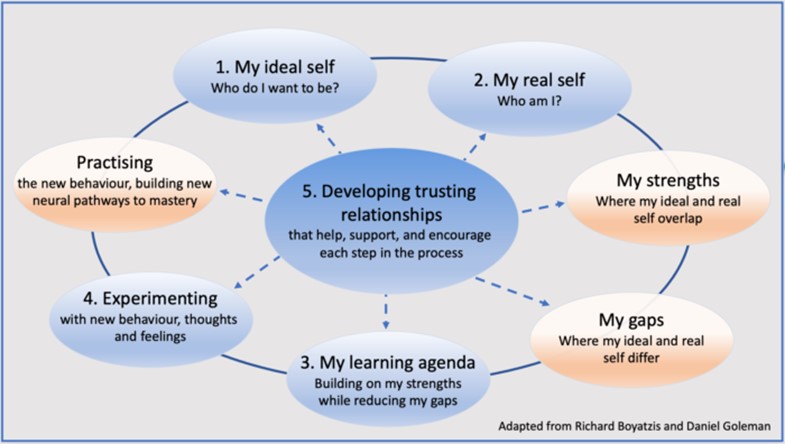

06. Intentional Change.Defining a powerful iterative learning cycle that we will utilise to develop our strategic thinking.

07. The Ideal Self and Real Self. Defining and describing our ideal self in relation to our current self, so that we can best construct our learning journey.

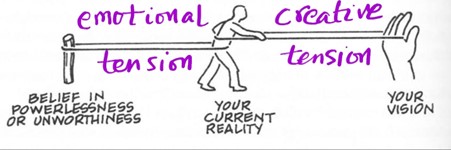

08. Creative Tension. Understanding and leveraging our desire to grow so that we can most effectively undertake our learning journey.

09. Creating a Learning Agenda. Defining those things that we need to learn and build knowledge on our way to achieving our ideal self.

10. Crafting your Learning Agenda. Enacting your learning agenda to practice those things that we have learnt in a safe environment.

11. Build your Trusted Support Network. Act out your learning agenda and practice those things that we have learnt in a safe manner, supported by your trusted network.

12. Complexity. Exploring the concept of complexity, and how the ever increasingly complex world around us requires new ways of thinking, action and being, so that we can make better and more informed decisions.

Strategies

The strategies that we apply in this course will follow the Intentional Change Model, utilising a mix of four different activities to work towards achieving the workshop objectives:

01. Researching. Reviewing the workshop material presented to you and undertaking your own research on topics that resonate with you, especially those that are applicable and relevant to your workplace.

02. Case Studies. Provided to you to highlight the application of theoretical principles and how they look in real-world situations to help with the connection between theory and practice.

03. Workplace Scenarios. An opportunity to implement the course content and applying the workshop material presented to you by investigating a scenario that is relevant to your workplace.

04. Learn by doing. Identifying new skills and knowledge that you have learned during the workshop, and trying them out with help from your support network.

Tasks

The following types of tasks will be utilised throughout this workshop to successfully achieve the objectives, as provided in the following description:

01. Personal Journal Reflections. As the workshop material is presented, you will be asked to observe and interpret, entering your reflections in your personal journal. Your entries will be your personal understanding of how you make sense of the situation presented, and actions that you might take.

02. Develop Simple Rules – Rules of Thumb. Defining simple rules is an easy and effective way to change behaviours. Suggestions will be made as we present the workshop material to suggest simple rules that serve to remind you about different ways to think, interpret and act in certain situations. These will be invaluable, easy to remember prompts upon completion of the entire program.

03. Engage in Creative Conversations. You will be encouraged to seek feedback on your thoughts by sharing your stories and insights during the workshop. These creative conversations will be designed to challenge your thinking by embracing the different opinions, understanding conflicting perspectives, and exploring the reasons for these.

04. Define and undertake a Workplace Project. The workplace project is designed to return the investment in this workshop back to your team, department and/or organisation. It will involve undertaking an investigation, conducting an analysis based on the workshop content presented, and making recommendations for improvements back to the business.

Personal Journal

Your personal journal is an important part of achieving the objectives. When done correctly, it is a powerful and profound method to document your thought processes, insights, and ideas, helping you to shift your thinking and your behaviours over time. Please take the time to invest in the reflection process and ensure that you embrace the following suggestions described below:

• Be fully present and proactive when going through the various exercises provided in the course manuals during the workshop.

• Be sure to plan sufficient time for the tasks required between each individual Workshop.

• Create your personal journal entries as you reflect.

• Gradually add your thoughts, insights, and ideas throughout the workshop, you don’t have to wait to the end.

• Remember that it is most effective to work continuously in an iterative process, i.e., small, and manageable changes in preference to once-off large step changes.

Reflection

Within the first 24-48 hours after the Workshop, take the time to reflect on the first Workshop to consider the following questions in your personal journal:

a. What was my personal key take-away from the Workshop?

b. Which learning struck me the most?

c. How has your actual self changed, and what is my new ideal self?

d. Do I have any doubts with regards to my ideal self?

e. Is there anything else I’d like to write down…?

Before the next workshop (if not already done so), identify your trusted support network. The purpose of your trusted support network is to help you to challenge your thoughts and provide a learning opportunity in a safe environment. Examples of types of people who you may wish to consider as part of your trusted support network include:

• Coach

• Mentor

• Role Model

• Partner

• Family member

• Your manager/team lead

You may wish to have several different people in your trusted support network, and they may fulfil different roles and offer you different types of support during your learning journey.

Introduction

Introduction

The first workshop in our Strategic Decision Making program focuses on providing participants with a foundational understanding of the concepts that underpin how we think. It involves delving into the subject in a multifaceted way, as it encompasses a variety of cognitive activities that are essential to human behaviour and learning, each offering unique insights into the nature of thought. The workshop will take you through different ways to process information, perceive patterns, and form thoughts and opinions based on your knowledge and experiences.

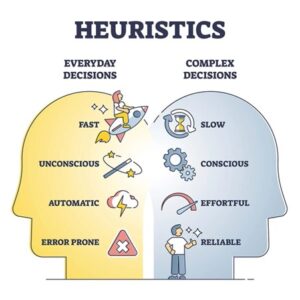

Thinking can be conscious or unconscious, and it can take various forms such as logical thinking, critical thinking, creative thinking, and abstract thinking. It involves mental activities such as perception, memory, attention, language processing, and problem-solving. Thinking is essential for human intelligence and plays a crucial role in decision-making, learning, and problem-solving. It allows individuals to process information, evaluate options, consider consequences, and make informed choices.

During this workshop, we will progressively strengthen the foundation of your ability to think strategically, increase your confidence to consider what is happening beyond what is presented at face value, and to benefit from the return of investment in yourself, your team, and your organisation.

Each month we will delves deeper into the thinking processes that lead you to develop better strategic decision making. A process that will provide the team in your organisation, with higher consciousness, greater insights, and the ability to plan into the predictable and unpredictable future.

The evolution of Strategic Thinking & Decision Making

Strategic thinking is a concept that has evolved over time and has been influenced by various disciplines and thinkers. Its evolution can be traced through various historical periods, reflecting the changing social, economic, technological, and political landscapes. This evolution has seen strategic thinking move from simple planning and warfare tactics to complex, multidimensional approaches in business, governance, and other areas. The evolution of strategic thinking can be broadly categorised into several general eras, each marked by distinct characteristics and contributions. These eras reflect the application of strategic thinking across various domains such as military, political, economic, and business contexts, as is evidenced in at least four ways.

1. PEOPLE. The great leaders of governments and of armies, and the contributions they made to leadership and to military art.

2. PAST CAMPAIGNS. Choices in military history and in time of socio-political conflict that remain relevant and are subject to subsequent evaluation.

3. PRINCIPLES. The very existence of principles of strategy is much debated, and many have sought to identify and establish enduring philosophies on how it is formulated.

4. PATTERNS. Patterns are more general and more timeless than the analyses of events and individual strategic choices. It represents a continuity in strategic thinking throughout modern history, as described in the following for more recent times:

Industrial Age

• The advent of the Industrial Revolution introduced new strategic dimensions in resource control and economic competition.

• The concept of total war, as seen in the American Civil War, reflected a shift in military strategy due to industrialisation.

• Strategic thinking began to extend into the economic realm with the rise of corporate competition and the need for market positioning.

20th Century Global Conflict and Cold War

• World Wars I and II demanded comprehensive national strategies involving economics, society, technology, and diplomacy.

• The Cold War era was characterized by geopolitical strategy, nuclear deterrence theory, and proxy wars.

• Game theory emerged, providing a mathematical approach to strategic decision-making.

Late 20th Century to Early 21st Century

• The information age brought about strategic considerations in technology and business innovation.

• Globalisation and the rise of multinational corporations led to strategic thinking in competitive advantage, market entry, and supply chain management.

• The concept of sustainable development introduced strategic planning in environmental, social, and economic domains.

Contemporary Era

• Rapid technological changes and digitalization require adaptive and innovative strategies in business and governance.

• Strategic thinking now includes considerations of global challenges, such as climate change, cybersecurity, and international terrorism.

• The rise of artificial intelligence and data analytics has transformed strategic decision-making processes, emphasizing predictive models and real-time adaptation.

Throughout these eras, strategic thinking has continually adapted to the challenges and complexities of the times. In each period, thinkers and leaders have developed and applied strategies that reflected the available technologies, social structures, and prevailing philosophies. Today, strategic thinking encompasses a diverse range of disciplines and is integral to navigating the complexities of a rapidly changing global landscape.

Current Approaches

There is an abundance of literature about strategy and strategic thinking. In general terms, strategic thinking seeks to identify and develop unique opportunities that create value for your organisation. Current approaches on strategic thinking aligns to the following four key characteristics:

1) Seeks to Influence because you cannot control

Strategic thinking recognises that the fundamental task of strategy is to influence the variable that the strategist does not control, and in the direction that the strategist desires. There are many unknowns and numerous factors that cannot be controlled in a manner that you would normally apply through good forms of management.

2) Existing and Predictive Information

Strategic thinking requires facility with a different kind of information than is normally used in business decisions. The object is to influence behaviour of people and related factors in the future. That means that there is no data because all data comes from the past. There is no data about the future. Thus, a strategic thinker needs to be comfortable with something other than statistically significant quantitative data. Strategic thinkers know that if they can’t depend on statistically significant quantitative data, they must make decisions based on something else. They become skilled at thinking and deciding based on a wide variety of information that is not statistically significant, not quantifiable, or may not even exist yet.

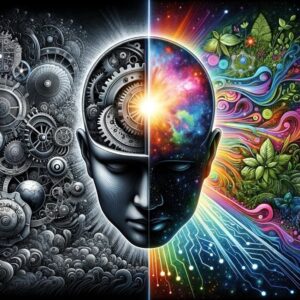

3) A balance between art and science

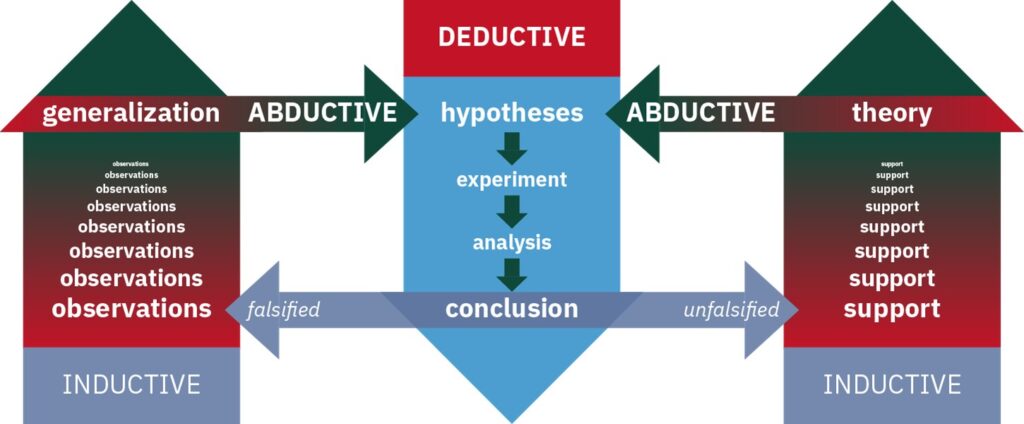

Strategic thinking must balance different forms of reasoning because of the various scenarios that are presented to us that has data, has no data, or comes with limited data. This requires a balance between intuition and analysis, sometime referred to as the balance between art and science. Strategists must employ a balance between these two extremes, and we can consider how to apply this in the following forms:

Deductive Reasoning

Deduction is generally defined as “the deriving of a conclusion by reasoning.” Its specific meaning in logic is “inference in which the conclusion about particulars follows necessarily from general or universal premises.” Simply put, deduction—or the process of deducing—is the formation of a conclusion based on generally accepted statements or facts.

Inductive Reasoning

Whereas in deduction the truth of the conclusion is guaranteed by the truth of the statements or facts considered, induction is a method of reasoning involving an element of probability. In logic, induction refers specifically to “inference of a generalised conclusion from particular instances.” In other words, it means forming a generalisation based on what is known or observed as your reasoning is based on an observation of a small group, as opposed to universal premises.

Abductive Reasoning

The third method of reasoning, abduction, is defined as “a syllogism in which the major premise is evident but the minor premise and therefore the conclusion only probable.” It involves forming a conclusion from the information that is known.

4) Considers Multiple Variables Simultaneously

Strategic thinking must consider many variables simultaneously, not sequentially or linearly. Thinking of them sequentially or linearly, which is too often done, is not strategic. It will cause localised optimisation of narrow solutions and may lead to unintended consequences more broadly. Sequential thinking on narrow variables will not be able to compel people to act in the desired way. Is it the power of an integrated set of choices across the various competitive variables that can compel action, not a sequence of independent choices.

In sum, strategic thinking entails comfort with using abductive reasoning and non-statistically significant data (qualitative, singular, analogous) on multiple variables to create a model about how you can influence, by actions on things you control, the future behaviour of the key thing you don’t control.

Future Outlook

The future of strategic decision making is likely to be shaped by several key trends:

1. Data-driven decision making: With the increasing availability of data and advanced analytics tools, organizations will rely more on data-driven insights to make strategic decisions. This includes leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to analyse large volumes of data and identify patterns, trends, and opportunities.

2. Real-time decision making: As technology continues to advance, decision-making processes will become faster and more agile. Real-time data and analytics will enable organizations to make decisions on the fly, responding quickly to changing market conditions and customer needs.

3. Collaborative decision making: Strategic decisions are often complex and require input from multiple stakeholders. In the future, decision-making processes will become more collaborative, involving cross-functional teams and leveraging tools that facilitate communication, collaboration, and consensus-building.

4. Scenario planning and predictive modelling: To mitigate risks and uncertainties, organizations will increasingly use scenario planning and predictive modelling techniques. These tools allow decision-makers to simulate different scenarios and assess the potential outcomes of their decisions, helping them make more informed choices.

5. Ethical decision making: As technology continues to advance, ethical considerations will play a more significant role in strategic decision making. Organizations will need to consider the ethical implications of their decisions, such as privacy concerns, data security, and the impact on society and the environment.

6. Automation and AI assistance: Automation and AI technologies will play a significant role in supporting strategic decision making. AI assistants can help decision-makers gather relevant information, analyse data, and provide insights, enabling them to make more informed and efficient decisions.

Overall, the future of strategic decision making will be characterised by data-driven insights, real-time decision-making processes, collaboration, scenario planning, ethical considerations, and the integration of automation and AI technologies.

Executive Summary

The world we live and work in has become increasingly complex and uncertain. The pace of change continues to escalate, and we face more disruptive events, behaviours, and trends than ever before. We require different thinking and different approaches, and we need to uplift our ability to deal with emergent and unpredictable challenges ahead. This workshop will seek to build an understanding of the ways in which we think and how we make sense of thinks. It will then introduce participants to the concepts of complexity and how this requires us to shift the way we think. We will explore various methodologies to help us navigate complexity in helping us to think differently and enhance our ability to make sense of the world around us. Embracing these principles will enhance the leader’s and managers ability to navigate the known and unknown challenges ahead, helping them to make more contextually suitable and effective decisions.

How we think is a complex and multifaceted process that involves various cognitive functions and skills. Here are twelve key aspects of thinking that we will cover in this course:

Chapter 1: Complex Times – New Mindset Part 1

Our mindset refers to the interaction of our attitudes, beliefs, and ways of thinking that shape how we interpret and respond to the world around us. It significantly influences our behaviour, our emotions, our interactions, and approach to challenges and opportunities. Importantly, it defines the way that we accumulate knowledge, sense-make, and create the parameters and condition that leads to how we make decisions. Thinking, also known as ‘cognition’, refers to the ability to process information, hold attention, store, and retrieve memories and select appropriate responses and actions. The ability to understand other people and express oneself to others can also be categorised under thinking.

In this course, we will explore ‘how we think’. It will help us to understand how we makes sense of the world around us and, as a result, how we make decisions. The decisions we make in a business environment will likely affect many people, however the way that we make decisions is different for every person. We will utilise the practice of personal reflection via journals to assist with this process, undertaking an iterative approach to learning about your own mindset and how to develop your strategic thinking.

Chapter 2: Understanding our mindset Part 2

The environment in which we live and go about our business has a profound influence on the way we think, shaping our cognitive processes, emotions, behaviours, and overall state of mind.

Our physical surroundings can have a substantial impact: a chaotic, noisy environment may scatter our attention and hinder concentration, while a serene and orderly space can facilitate clear thinking and focus. Natural settings have been shown to improve cognitive functions and promote relaxation, enabling more creative and expansive thought patterns. Social environments also play a critical role; the cultural context in which we are immersed from birth instils specific value systems and ways of reasoning, subtly directing our thought processes along particular paths. Our socio-economic environment can exert stressors that affect cognitive resources, limiting our ability to engage in complex problem-solving or forward planning. Access to education and a wealth of learning resources can enhance our critical thinking skills and open-mindedness.

In sum, the interplay of these factors coupled with our innate sense-making, guides the evolution of our thought processes, moulding the unique cognitive landscapes we each inhabit. Each aspect of our environment can interact with individual factors like genetics, personal experiences, and personality, creating a complex web of influences on our cognitive processes and mental well-being. Understanding these environmental impacts is crucial for creating healthier spaces, both physically and socially, to foster more effective thinking and well-being.

Chapter 3: Biases & Heuristics Part 3

Biases and heuristics are essential concepts in cognitive psychology, describing systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment and decision-making. They are mental shortcuts or “rules of thumb” that often help us make quick decisions but can also lead to errors in thinking. These biases and heuristics are hardwired into our thinking processes, likely because they offer a mental shortcut in decision-making, saving time and energy. To prevent us, or at least forewarning us in making flawed judgments and irrational decisions, we need to identify the conditions in which these biases and heuristics may occur, and how we should individually and collectively treat them, especially in complex or unfamiliar situations. Understanding these can help in developing strategies to mitigate their effects, leading to more rational decision-making.

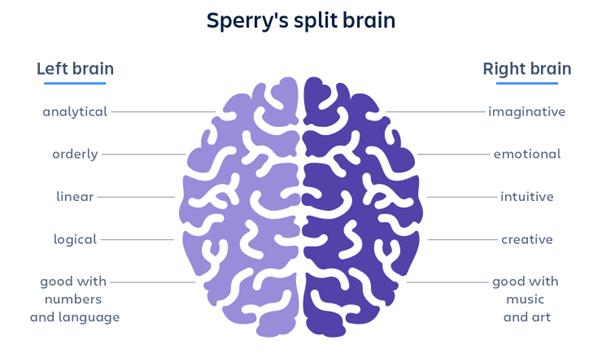

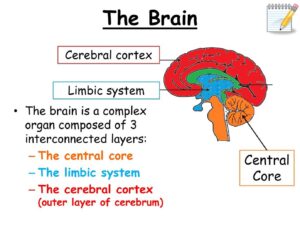

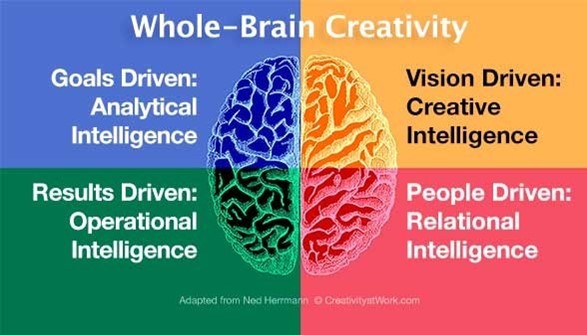

Chapter 4: Our Thinking Audit. Part 4

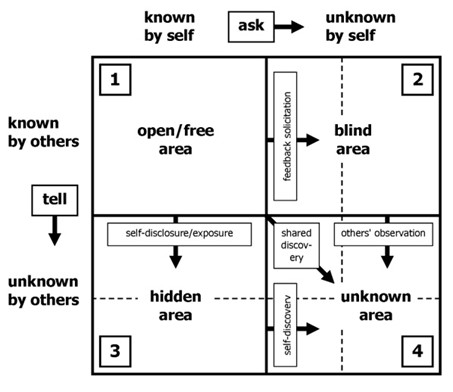

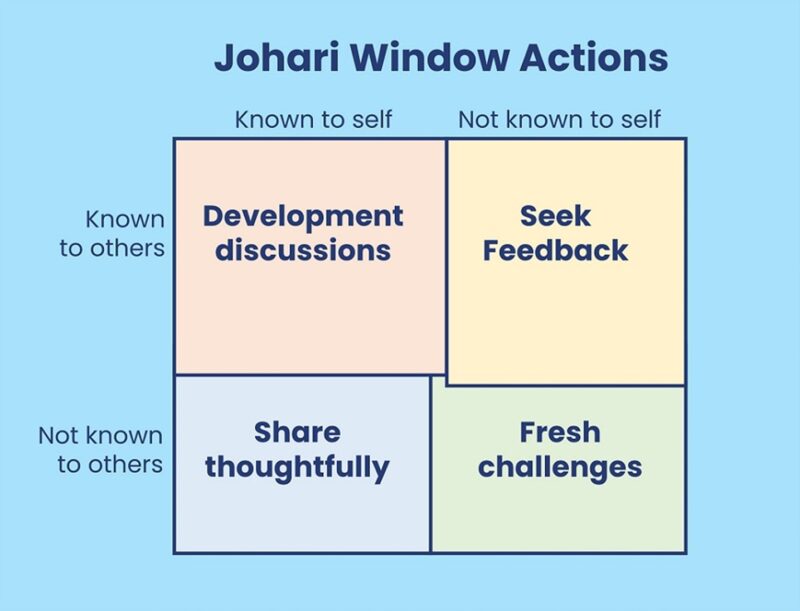

Have you ever stopped and reflected about the way that you think? It is not often that we stop to do this, and yet the way that we think forms an integral part of our lives that influences the way that we act, behave, and make decisions. In this course, we will leverage the principles of neuroscience to unpack the way that we think so that we can better understand our own thinking preferences and identify the thinking preferences of others.

A “thinking audit” is not a standard term that you will find in cognitive science or psychology, however, will undertake one in this course as a self-reflective exercise intended to help you reflect and understand your own thought processes. By doing this, it will also help you to better identify these same characteristics in others, especially how the thought processes of yourself and others impact your decision-making preferences. This involves examining the ways you think, the biases that influence you, the quality of your decision-making, and the effectiveness of your problem-solving strategies.

A thinking audit should ideally be an ongoing process, not a one-time event. In this course, we will utilise your learning journal and an iterative approach to facilitate your learning. Progressively taking stock of how you think and making conscious efforts to improve your cognitive processes can lead to better decision-making, enhanced problem-solving abilities, and greater overall mental clarity.

Chapter 5: Personal Mastery Part 5

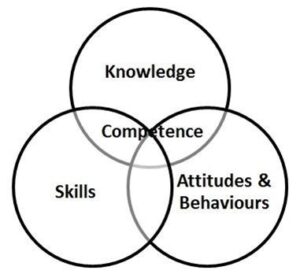

Personal Mastery is the process of living and working purposefully towards a vision and/or a desired outcome. This is usually in alignment with one’s values and in a state of constant learning about oneself and the reality in which one exists. As a concept, it is often discussed in the context of personal development and leadership. It’s about achieving a high level of proficiency and understanding in the areas that matter most to an individual’s life and career.

Personal mastery goes beyond mere competence or skills; it encompasses a deep commitment to lifelong learning, growth, and self-improvement. In his book “The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organisation,” Peter Senge describes Personal Mastery as one of the five disciplines that form the foundation of a learning organisation. Senge’s concept of personal mastery goes beyond competence and skills, though it encompasses them. It is about creating a discipline of personal growth and learning, where an individual is committed to continually clarifying and deepening their personal vision, focusing their energies, developing patience, and seeing reality objectively.

Chapter 6: Intentional Change Part 6

How do people make changes in their behaviour? What does it take to make lasting change?

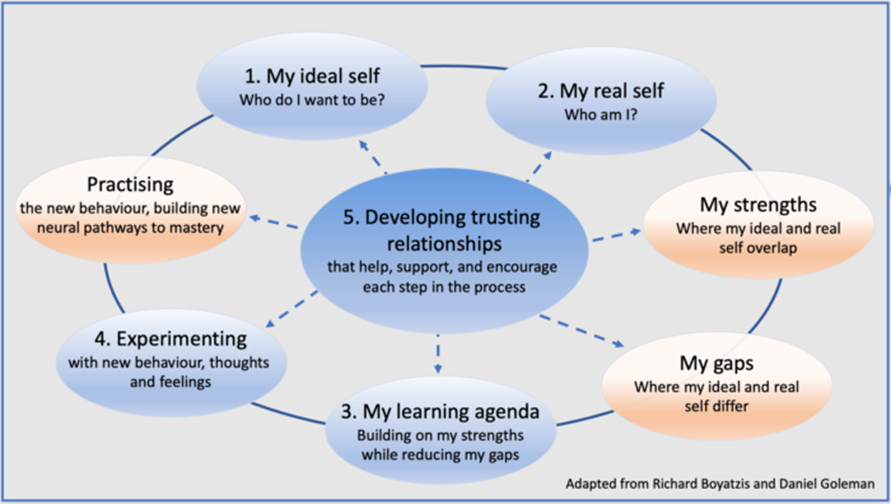

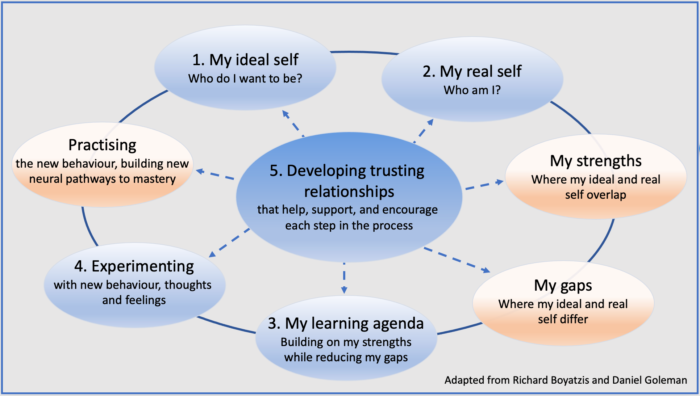

These are questions that many people have asked, and embarked upon a change journey that comes in many forms. In this workshop we will utilise Intentional Change Theory. It facilitates change at multiple levels and through numerous iterations in preference to one big step-change. The Intentional Change model encompasses “the five discoveries”, as follows:

1. The ideal self and a personal vision

2. The real self and its comparison to the ideal self, resulting in an assessment of one’s strengths and weaknesses, in a sense our personal balance sheet or our toolkit.

3. A learning agenda and plan

4. Experimentation and practice with the new behaviour, thoughts, feelings, or perceptions

5. Trusting, or resonant, relationships that enable a person to experience and process each discovery in the process.

Participants undertaking this workshop will pass through these discoveries in a cycle that repeats as the person changes. Let’s look at each of these discoveries.

Chapter 7: The Ideal and Real Self Part 7

Before making an intentional change, we need to discover and understand, to some degree, who we want to be, whether as an individual, a team, a project and/or an organisation. We will generically refer to these as ‘self’. Once discovered, then we can turn our attention to the gap that exists in between our ideal and real self, specific to the goal of become better strategic thinkers, to understand:

What we call our “ideal self” is an image of the character of the individual, team, project and/or organisation that we want to be.

The “real self” is about understanding and accepting one’s current state, including strengths, weaknesses, and the discrepancies between one’s current reality and their aspirations or ideal self. This acceptance is not about resignation but serves as a starting point for intentional, positive change. In fact, lasting change is more likely when it is self-directed and focuses on developing what is right about a person rather than fixing what is wrong.

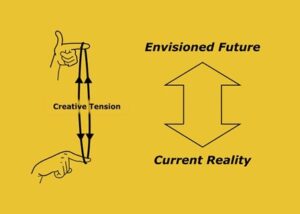

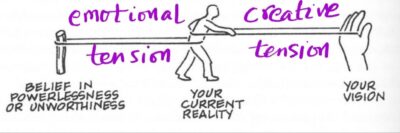

Chapter 8: Creative Tension Part 8

Once you have a sense of your ideal self, it’s time to look at how that ideal self compares with your current “real” self. The real self is the person that other people see and with whom they interact. Creative tension represents the gap between our vision for the future (ideal self) and our understanding of our current reality (real self), or between what is and what we desire it to be. This tension is considered “creative” because it can be a powerful driver of change, innovation, and growth, motivating individuals and organisations to move towards their vision or goals.

However, when we back off from our true aspirations, or lie to ourselves about current reality, we undermine the creative tension that is essential if we want to ensure the path of least resistance draws us to our genuinely desired future self. Similarly, when we rush into half-baked, quick fix ‘solutions’, we fail to establish the much more powerful underlying structural tension dynamic that brings into play our deeper resourcefulness. This force is known as emotional tension, a state of mental or emotional strain, often arising from situations that evoke conflicting feelings, stress, or anxiety. This tension can be the result of various factors, including personal conflicts, unmet needs, unresolved issues, or challenging circumstances. It manifests in various ways, including feelings of unease, restlessness, frustration, or distress. Emotional tension can impact an individual’s mood, behaviour, and overall mental health, influencing their interactions with others and their ability to cope with daily activities.

Chapter 9: Creating a Learning Agenda Part 9

Once you have a vision for the future and an accurate sense of your current self, it is time to develop a plan for how to move toward your vision. A learning agenda is an intentional structured plan that outlines the key questions, activities, and resources needed to gain knowledge and develop skills in a specific area. In this case, it specifically serves as a roadmap for those seeking to address knowledge gaps, improve decision-making, and achieve specific learning goals associated with their strategic thinking, which can be accomplished individually and/or as a team. The output is on creating that learning agenda. Such a plan would focus on development and is most effective if it is coupled with a positive belief in one’s capability and hope of improvement. A learning plan would also include standards of performance set by the person who is pursuing change. Once the plan is in place, the next step is to try it out.

Chapter 10: Crafting your Learning Environment Part 10

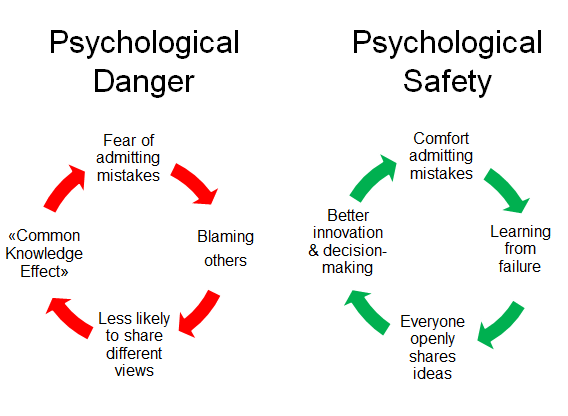

Once you have defined your learning agenda, i.e., what you wish to learn and how you wish to learn it, it is time to put it into practice. Depending on your goals, this often means experimenting with new behaviour. After such practice, you should reflect on what happened, and experiment further. Sometimes practicing new behaviour can happen in a course or a controlled learning environment, but often it happens in real world settings such as at work or at home. Whatever the situation, experimentation will be most effective in conditions where you feel safe. Such psychological safety means that you can try out your new behaviour with less risk of embarrassment or serious consequences of failure.

Chapter 11: Trusted Support Network Part 11

Our relationships with other people are an important part of our everyday environment. Crucial to our ability to change are the relationships and groups that are particularly important to us, i.e., our Trusted Support Network. They provide the context in which we can see our progress on our desired changes. Often, our relationships and groups can be sources of support for our change as well as for feedback.

Our Trusted Support Network helps us from slipping back into our former ways of behaving, and plays a crucial role in fostering personal and professional growth. It is an integral when undertaking your learning agenda as it offers a foundation for advice, feedback, emotional support, and opportunities. When established, it can help you to navigate challenges, make informed decisions, and achieve your goals. It is invaluable, especially when coupled with an environment where individuals can thrive, facing challenges with resilience and confidence, have no fear of failure, while also contributing to the growth and well-being of others in the network.

Chapter 12: Strategic Thinking for a Complex World part 12

The topic of complexity has become increasingly important concept in our modern and rapidly changing world. It is a crucial lens through which we make sense of, adapt to, and even harness the intricate web of interactions that define our rapidly evolving world. At its core, complexity recognises that many phenomena and situations are far from simple and linear; rather, they emerge from the interdependencies, feedback loops, and non-linear relationships between various elements. Different thinking is required if we are to makes sense of complexity. This is not merely an academic pursuit as it requires us to bring our whole self to the stage, and to bring a strategic mindset to systemically appreciate the whole picture rather than simply treat the numerous smaller problems presented to us.

Complexity and strategic thinking are deeply interconnected concepts. Complexity refers to the degree of interconnectivity and interdependence in systems or problems, where numerous components and variables interact in ways that can be difficult to predict. Strategic thinking, then, is the process of identifying long-term goals and determining the best approach to achieve those goals, especially in complex situations. It involves understanding the intricate dynamics at play, anticipating potential changes, and making decisions that navigate through these complexities effectively.

Curriculum

Strategic Decision Making – Workshop 1 – Understanding how we think

- Complex times – new thinking.

- Understanding our mindset

- Biases & Heuristics

- Our Thinking Audit

- Personal Mastery

- Intentional Change

- The Ideal Self and Real Self

- Creative Tension

- Creating a Learning Agenda

- Crafting your Learning Environment.

- Build your trusted support network

- Strategic Thinking for a Complex World

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Strategic Decision Making corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast

As a guide, the Appleton Greene Strategic Decision Making corporate training program should take 12-18 months to complete, depending upon your availability and current commitments. The reason why there is such a variance in time estimates is because every student is an individual, with differing productivity levels and different commitments. These differentiations are then exaggerated by the fact that this is a distance-learning program, which incorporates the practical integration of academic theory as an as a part of the training program. Consequently all of the project studies are real, which means that important decisions and compromises need to be made. You will want to get things right and will need to be patient with your expectations in order to ensure that they are. We would always recommend that you are prudent with your own task and time forecasts, but you still need to develop them and have a clear indication of what are realistic expectations in your case. With reference to your time planning: consider the time that you can realistically dedicate towards study with the program every week; calculate how long it should take you to complete the program, using the guidelines featured here; then break the program down into logical modules and allocate a suitable proportion of time to each of them, these will be your milestones; you can create a time plan by using a spreadsheet on your computer, or a personal organizer such as MS Outlook, you could also use a financial forecasting software; break your time forecasts down into manageable chunks of time, the more specific you can be, the more productive and accurate your time management will be; finally, use formulas where possible to do your time calculations for you, because this will help later on when your forecasts need to change in line with actual performance. With reference to your task planning: refer to your list of tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve your program objectives; with reference to your time plan, calculate when each task should be implemented; remember that you are not estimating when your objectives will be achieved, but when you will need to focus upon implementing the corresponding tasks; you also need to ensure that each task is implemented in conjunction with the associated training modules which are relevant; then break each single task down into a list of specific to do’s, say approximately ten to do’s for each task and enter these into your study plan; once again you could use MS Outlook to incorporate both your time and task planning and this could constitute your study plan; you could also use a project management software like MS Project. You should now have a clear and realistic forecast detailing when you can expect to be able to do something about undertaking the tasks to achieve your program objectives.

Performance management

It is one thing to develop your study forecast, it is quite another to monitor your progress. Ultimately it is less important whether you achieve your original study forecast and more important that you update it so that it constantly remains realistic in line with your performance. As you begin to work through the program, you will begin to have more of an idea about your own personal performance and productivity levels as a distance-learner. Once you have completed your first study module, you should re-evaluate your study forecast for both time and tasks, so that they reflect your actual performance level achieved. In order to achieve this you must first time yourself while training by using an alarm clock. Set the alarm for hourly intervals and make a note of how far you have come within that time. You can then make a note of your actual performance on your study plan and then compare your performance against your forecast. Then consider the reasons that have contributed towards your performance level, whether they are positive or negative and make a considered adjustment to your future forecasts as a result. Given time, you should start achieving your forecasts regularly.

With reference to time management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual time taken in your study plan; consider your successes with time-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; consider your failures with time-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to time planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your time expectations. You need to be consistent with your time management, otherwise you will never complete your studies. This will either be because you are not contributing enough time to your studies, or you will become less efficient with the time that you do allocate to your studies. Remember, if you are not in control of your studies, they can just become yet another cause of stress for you.

With reference to your task management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual tasks that you have undertaken in your study plan; consider your successes with task-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case; take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; consider your failures with task-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to task planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your task expectations. You need to be consistent with your task management, otherwise you will never know whether you are achieving your program objectives or not.

Keeping in touch

You will have access to qualified and experienced professors and tutors who are responsible for providing tutorial support for your particular training program. So don’t be shy about letting them know how you are getting on. We keep electronic records of all tutorial support emails so that professors and tutors can review previous correspondence before considering an individual response. It also means that there is a record of all communications between you and your professors and tutors and this helps to avoid any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation. If you have a problem relating to the program, share it with them via email. It is likely that they have come across the same problem before and are usually able to make helpful suggestions and steer you in the right direction. To learn more about when and how to use tutorial support, please refer to the Tutorial Support section of this student information guide. This will help you to ensure that you are making the most of tutorial support that is available to you and will ultimately contribute towards your success and enjoyment with your training program.

Work colleagues and family

You should certainly discuss your program study progress with your colleagues, friends and your family. Appleton Greene training programs are very practical. They require you to seek information from other people, to plan, develop and implement processes with other people and to achieve feedback from other people in relation to viability and productivity. You will therefore have plenty of opportunities to test your ideas and enlist the views of others. People tend to be sympathetic towards distance-learners, so don’t bottle it all up in yourself. Get out there and share it! It is also likely that your family and colleagues are going to benefit from your labors with the program, so they are likely to be much more interested in being involved than you might think. Be bold about delegating work to those who might benefit themselves. This is a great way to achieve understanding and commitment from people who you may later rely upon for process implementation. Share your experiences with your friends and family.

Making it relevant

The key to successful learning is to make it relevant to your own individual circumstances. At all times you should be trying to make bridges between the content of the program and your own situation. Whether you achieve this through quiet reflection or through interactive discussion with your colleagues, client partners or your family, remember that it is the most important and rewarding aspect of translating your studies into real self-improvement. You should be clear about how you want the program to benefit you. This involves setting clear study objectives in relation to the content of the course in terms of understanding, concepts, completing research or reviewing activities and relating the content of the modules to your own situation. Your objectives may understandably change as you work through the program, in which case you should enter the revised objectives on your study plan so that you have a permanent reminder of what you are trying to achieve, when and why.

Distance-learning check-list

Prepare your study environment, your study tools and rules.

Undertake detailed self-assessment in terms of your ability as a learner.

Create a format for your study plan.

Consider your study objectives and tasks.

Create a study forecast.

Assess your study performance.

Re-evaluate your study forecast.

Be consistent when managing your study plan.

Use your Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) for tutorial support.

Make sure you keep in touch with those around you.

Tutorial Support

Programs

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. They are implemented over a sustainable period of time and professional support is consistently provided by qualified learning providers and specialist consultants.

Support available

You will have a designated Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and an Accredited Consultant and we encourage you to communicate with them as much as possible. In all cases tutorial support is provided online because we can then keep a record of all communications to ensure that tutorial support remains consistent. You would also be forwarding your work to the tutorial support unit for evaluation and assessment. You will receive individual feedback on all of the work that you undertake on a one-to-one basis, together with specific recommendations for anything that may need to be changed in order to achieve a pass with merit or a pass with distinction and you then have as many opportunities as you may need to re-submit project studies until they meet with the required standard. Consequently the only reason that you should really fail (CLP) is if you do not do the work. It makes no difference to us whether a student takes 12 months or 18 months to complete the program, what matters is that in all cases the same quality standard will have been achieved.

Support Process

Please forward all of your future emails to the designated (CLP) Tutorial Support Unit email address that has been provided and please do not duplicate or copy your emails to other AGC email accounts as this will just cause unnecessary administration. Please note that emails are always answered as quickly as possible but you will need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general tutorial support emails during busy periods, because emails are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. You will also need to allow a period of up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Please therefore kindly allow for this within your time planning. All communications are managed online via email because it enables tutorial service support managers to review other communications which have been received before responding and it ensures that there is a copy of all communications retained on file for future reference. All communications will be stored within your personal (CLP) study file here at Appleton Greene throughout your designated study period. If you need any assistance or clarification at any time, please do not hesitate to contact us by forwarding an email and remember that we are here to help. If you have any questions, please list and number your questions succinctly and you can then be sure of receiving specific answers to each and every query.

Time Management

It takes approximately 1 Year to complete the Strategic Decision Making corporate training program, incorporating 12 x 6-hour monthly workshops. Each student will also need to contribute approximately 4 hours per week over 1 Year of their personal time. Students can study from home or work at their own pace and are responsible for managing their own study plan. There are no formal examinations and students are evaluated and assessed based upon their project study submissions, together with the quality of their internal analysis and supporting documents. They can contribute more time towards study when they have the time to do so and can contribute less time when they are busy. All students tend to be in full time employment while studying and the Strategic Decision Making program is purposely designed to accommodate this, so there is plenty of flexibility in terms of time management. It makes no difference to us at Appleton Greene, whether individuals take 12-18 months to complete this program. What matters is that in all cases the same standard of quality will have been achieved with the standard and bespoke programs that have been developed.

Distance Learning Guide

The distance learning guide should be your first port of call when starting your training program. It will help you when you are planning how and when to study, how to create the right environment and how to establish the right frame of mind. If you can lay the foundations properly during the planning stage, then it will contribute to your enjoyment and productivity while training later. The guide helps to change your lifestyle in order to accommodate time for study and to cultivate good study habits. It helps you to chart your progress so that you can measure your performance and achieve your goals. It explains the tools that you will need for study and how to make them work. It also explains how to translate academic theory into practical reality. Spend some time now working through your distance learning guide and make sure that you have firm foundations in place so that you can make the most of your distance learning program. There is no requirement for you to attend training workshops or classes at Appleton Greene offices. The entire program is undertaken online, program course manuals and project studies are administered via the Appleton Greene web site and via email, so you are able to study at your own pace and in the comfort of your own home or office as long as you have a computer and access to the internet.

How To Study

The how to study guide provides students with a clear understanding of the Appleton Greene facilitation via distance learning training methods and enables students to obtain a clear overview of the training program content. It enables students to understand the step-by-step training methods used by Appleton Greene and how course manuals are integrated with project studies. It explains the research and development that is required and the need to provide evidence and references to support your statements. It also enables students to understand precisely what will be required of them in order to achieve a pass with merit and a pass with distinction for individual project studies and provides useful guidance on how to be innovative and creative when developing your Unique Program Proposition (UPP).

Tutorial Support

Tutorial support for the Appleton Greene Strategic Decision Making corporate training program is provided online either through the Appleton Greene Client Support Portal (CSP), or via email. All tutorial support requests are facilitated by a designated Program Administration Manager (PAM). They are responsible for deciding which professor or tutor is the most appropriate option relating to the support required and then the tutorial support request is forwarded onto them. Once the professor or tutor has completed the tutorial support request and answered any questions that have been asked, this communication is then returned to the student via email by the designated Program Administration Manager (PAM). This enables all tutorial support, between students, professors and tutors, to be facilitated by the designated Program Administration Manager (PAM) efficiently and securely through the email account. You will therefore need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general support queries and up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies, because all tutorial support requests are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Consequently you need to put some thought into the management of your tutorial support procedure in order to ensure that your study plan is feasible and to obtain the maximum possible benefit from tutorial support during your period of study. Please retain copies of your tutorial support emails for future reference. Please ensure that ALL of your tutorial support emails are set out using the format as suggested within your guide to tutorial support. Your tutorial support emails need to be referenced clearly to the specific part of the course manual or project study which you are working on at any given time. You also need to list and number any questions that you would like to ask, up to a maximum of five questions within each tutorial support email. Remember the more specific you can be with your questions the more specific your answers will be too and this will help you to avoid any unnecessary misunderstanding, misinterpretation, or duplication. The guide to tutorial support is intended to help you to understand how and when to use support in order to ensure that you get the most out of your training program. Appleton Greene training programs are designed to enable you to do things for yourself. They provide you with a structure or a framework and we use tutorial support to facilitate students while they practically implement what they learn. In other words, we are enabling students to do things for themselves. The benefits of distance learning via facilitation are considerable and are much more sustainable in the long-term than traditional short-term knowledge sharing programs. Consequently you should learn how and when to use tutorial support so that you can maximize the benefits from your learning experience with Appleton Greene. This guide describes the purpose of each training function and how to use them and how to use tutorial support in relation to each aspect of the training program. It also provides useful tips and guidance with regard to best practice.

Tutorial Support Tips

Students are often unsure about how and when to use tutorial support with Appleton Greene. This Tip List will help you to understand more about how to achieve the most from using tutorial support. Refer to it regularly to ensure that you are continuing to use the service properly. Tutorial support is critical to the success of your training experience, but it is important to understand when and how to use it in order to maximize the benefit that you receive. It is no coincidence that those students who succeed are those that learn how to be positive, proactive and productive when using tutorial support.

Be positive and friendly with your tutorial support emails

Remember that if you forward an email to the tutorial support unit, you are dealing with real people. “Do unto others as you would expect others to do unto you”. If you are positive, complimentary and generally friendly in your emails, you will generate a similar response in return. This will be more enjoyable, productive and rewarding for you in the long-term.

Think about the impression that you want to create

Every time that you communicate, you create an impression, which can be either positive or negative, so put some thought into the impression that you want to create. Remember that copies of all tutorial support emails are stored electronically and tutors will always refer to prior correspondence before responding to any current emails. Over a period of time, a general opinion will be arrived at in relation to your character, attitude and ability. Try to manage your own frustrations, mood swings and temperament professionally, without involving the tutorial support team. Demonstrating frustration or a lack of patience is a weakness and will be interpreted as such. The good thing about communicating in writing, is that you will have the time to consider your content carefully, you can review it and proof-read it before sending your email to Appleton Greene and this should help you to communicate more professionally, consistently and to avoid any unnecessary knee-jerk reactions to individual situations as and when they may arise. Please also remember that the CLP Tutorial Support Unit will not just be responsible for evaluating and assessing the quality of your work, they will also be responsible for providing recommendations to other learning providers and to client contacts within the Appleton Greene global client network, so do be in control of your own emotions and try to create a good impression.

Remember that quality is preferred to quantity

Please remember that when you send an email to the tutorial support team, you are not using Twitter or Text Messaging. Try not to forward an email every time that you have a thought. This will not prove to be productive either for you or for the tutorial support team. Take time to prepare your communications properly, as if you were writing a professional letter to a business colleague and make a list of queries that you are likely to have and then incorporate them within one email, say once every month, so that the tutorial support team can understand more about context, application and your methodology for study. Get yourself into a consistent routine with your tutorial support requests and use the tutorial support template provided with ALL of your emails. The (CLP) Tutorial Support Unit will not spoon-feed you with information. They need to be able to evaluate and assess your tutorial support requests carefully and professionally.

Be specific about your questions in order to receive specific answers

Try not to write essays by thinking as you are writing tutorial support emails. The tutorial support unit can be unclear about what in fact you are asking, or what you are looking to achieve. Be specific about asking questions that you want answers to. Number your questions. You will then receive specific answers to each and every question. This is the main purpose of tutorial support via email.

Keep a record of your tutorial support emails

It is important that you keep a record of all tutorial support emails that are forwarded to you. You can then refer to them when necessary and it avoids any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation.

Individual training workshops or telephone support

Tutorial Support Email Format

You should use this tutorial support format if you need to request clarification or assistance while studying with your training program. Please note that ALL of your tutorial support request emails should use the same format. You should therefore set up a standard email template, which you can then use as and when you need to. Emails that are forwarded to Appleton Greene, which do not use the following format, may be rejected and returned to you by the (CLP) Program Administration Manager. A detailed response will then be forwarded to you via email usually within 20 business days of receipt for general support queries and 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Your tutorial support request, together with the corresponding TSU reply, will then be saved and stored within your electronic TSU file at Appleton Greene for future reference.

Subject line of your email

Please insert: Appleton Greene (CLP) Tutorial Support Request: (Your Full Name) (Date), within the subject line of your email.

Main body of your email

Please insert:

1. Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) Tutorial Support Request

2. Your Full Name

3. Date of TS request

4. Preferred email address

5. Backup email address

6. Course manual page name or number (reference)

7. Project study page name or number (reference)

Subject of enquiry

Please insert a maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Briefly outline the subject matter of your inquiry, or what your questions relate to.

Question 1

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Question 3

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Question 4

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Question 5

Maximum of 50 words (please be succinct)

Please note that a maximum of 5 questions is permitted with each individual tutorial support request email.

Procedure

* List the questions that you want to ask first, then re-arrange them in order of priority. Make sure that you reference them, where necessary, to the course manuals or project studies.

* Make sure that you are specific about your questions and number them. Try to plan the content within your emails to make sure that it is relevant.

* Make sure that your tutorial support emails are set out correctly, using the Tutorial Support Email Format provided here.

* Save a copy of your email and incorporate the date sent after the subject title. Keep your tutorial support emails within the same file and in date order for easy reference.

* Allow up to 20 business days for a response to general tutorial support emails and up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies, because detailed individual responses will be made in all cases and tutorial support emails are answered strictly within the order in which they are received.

* Emails can and do get lost. So if you have not received a reply within the appropriate time, forward another copy or a reminder to the tutorial support unit to be sure that it has been received but do not forward reminders unless the appropriate time has elapsed.

* When you receive a reply, save it immediately featuring the date of receipt after the subject heading for easy reference. In most cases the tutorial support unit replies to your questions individually, so you will have a record of the questions that you asked as well as the answers offered. With project studies however, separate emails are usually forwarded by the tutorial support unit, so do keep a record of your own original emails as well.

* Remember to be positive and friendly in your emails. You are dealing with real people who will respond to the same things that you respond to.

* Try not to repeat questions that have already been asked in previous emails. If this happens the tutorial support unit will probably just refer you to the appropriate answers that have already been provided within previous emails.

* If you lose your tutorial support email records you can write to Appleton Greene to receive a copy of your tutorial support file, but a separate administration charge may be levied for this service.

How To Study

Your Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and Accredited Consultant can help you to plan a task list for getting started so that you can be clear about your direction and your priorities in relation to your training program. It is also a good way to introduce yourself to the tutorial support team.

Planning your study environment

Your study conditions are of great importance and will have a direct effect on how much you enjoy your training program. Consider how much space you will have, whether it is comfortable and private and whether you are likely to be disturbed. The study tools and facilities at your disposal are also important to the success of your distance-learning experience. Your tutorial support unit can help with useful tips and guidance, regardless of your starting position. It is important to get this right before you start working on your training program.

Planning your program objectives