Level 5 Leader – WDP1 (Mastering Self)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Level 5 Leader is provided by Dr. Gottfredson Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Dr. Gottfredson, Ph.D. is a cutting-edge leadership development author, researcher, and consultant. He helps organizations vertically develop their leaders primarily through a focus on mindsets. Ryan is the Wall Street Journal and USA Today best-selling author of two groundbreaking books.

He is the founder and owner of his consulting company, where he specializes in elevating leaders and executive teams in a manner that elevates the organization and its culture. He has worked with top leadership teams at CVS Health (top 130 leaders), Deutsche Telekom (500+ of their top 2,000 leaders), Experian, and others. He has also partnered with dozens of organizations (e.g., Federal Reserve Bank, Nationwide Insurance, Cook Medical) to develop thousands of mid-level managers and high-level leaders.

He is also a leadership professor at the College of Business and Economics at California State University-Fullerton. He holds a Ph.D. in Organizational Behavior and Human Resources from Indiana University, and a B.A. from Brigham Young University. As a respected authority and researcher on topics related to leadership, management, and organizational behavior, Ryan has published over 20 articles across a variety of journals including: Leadership Quarterly, Journal of Management, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Business Horizons, Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, and Journal of Leadership Studies. His research has been cited over 4,600 times since 2019.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

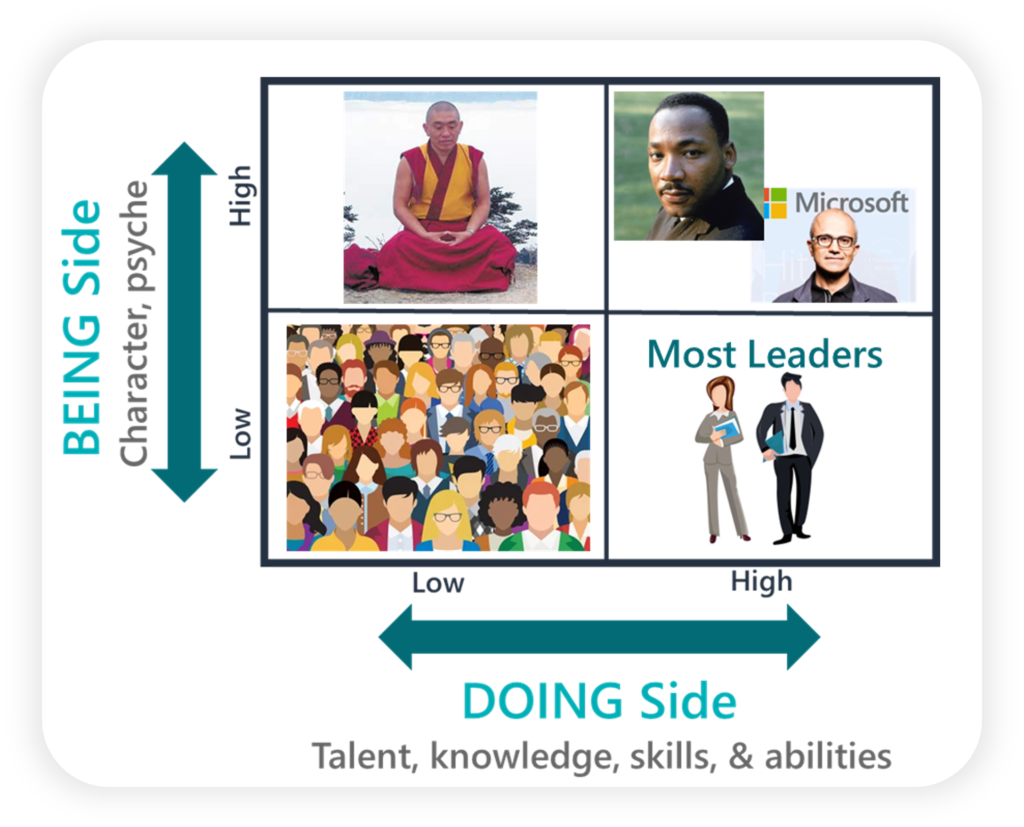

“Level 5” leadership is about becoming someone that others want to follow. In order for us to become someone others want to follow, we must become a master of ourselves. In this session, participants will discover that they have a “DOING Side” and a “BEING Side.” Our DOING Side is our level of talent, knowledge, skills, and abilities. Our BEING Side involves the programming of our body’s internal operating system. Participants will then explore the role their BEING Side plays in their “self-leadership” and leadership operations. This will be the start of a multi-stage effort to deepen participants’ self-awareness to foster self-leadership. Level 5” leadership does not come about by simply doing the “right things.” “

Objectives

01. Leadership Levels: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Lesson of Leadership: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. The Two Sides of Ourselves: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Common Leadership Issues: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Exemplary Leadership: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. What is Our Being Side?: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Meaning Making: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Window of Tolerance: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Psychological Trauma: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Our Current Culture: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Neurodivergence: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Elevated Leadership: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Leadership Levels: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Lesson of Leadership: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. The Two Sides of Ourselves: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Common Leadership Issues: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Exemplary Leadership: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. What is Our Being Side?: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Meaning Making: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Window of Tolerance: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Psychological Trauma: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Our Current Culture: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Neurodivergence: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Elevated Leadership: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Leadership Levels.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Lesson of Leadership.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze The Two Sides of Ourselves.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Common Leadership Issues.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Exemplary Leadership.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze What is Our Being Side?.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Meaning Making.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Window of Tolerance.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Psychological Trauma.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Our Current Culture.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Neurodivergence.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Elevated Leadership.

Introduction

The Core Objective of the Workshop

In the realm of leadership development, most programs begin with a focus on developing greater knowledge and skills around communication strategies, delegation tools, vision casting, or change management frameworks, as examples. While these are all valuable, we believe there is a deeper starting point—one that is critical for transformational leadership improvement.

This workshop starts with that deeper question: Who are you being as a leader?

The core objective of this workshop is simple in its phrasing but profound in its implications:

To introduce participants to their “Being Side” and to plant the seed for transformational leadership growth by helping them begin to elevate it.

Most leaders are highly familiar with their “Doing Side”—their knowledge, skills, technical competencies, and behaviors. Our workplaces train, reward, and promote people based on this side. But few leaders are familiar with their “Being Side”—the internal operating system that governs how they think, how they see the world, how they relate to others, and how they show up in moments of stress and complexity.

This is unfortunate, because our Being Side is what truly defines the quality of our leadership.

If we want to grow as leaders in a way that is not merely additive but transformative, we must go beyond doing more. We must become more. That is what this workshop is about.

To better understand this distinction, consider the example of an iPad. You can always download new apps to expand its functionality—this is like building our Doing Side by acquiring more tools and techniques. But at some point, adding new apps becomes less effective if the iPad’s internal operating system is outdated. The apps may crash, slow down, or conflict with each other. Real, sustainable improvement only comes when the iPad’s core operating system is upgraded. This is the work of the Being Side—elevating the underlying system that governs how we operate.

That’s what we are doing in this workshop: upgrading the internal operating system of leadership.

While much of leadership development has focused on the “apps”—communication models, personality assessments, decision-making frameworks—very few programs have focused on upgrading the operating system. This is not because it’s unimportant. Rather, it’s because the Being Side has historically been harder to measure, less well understood, and more introspective. It doesn’t lend itself to quick-fix techniques or easily digestible checklists. But what we’ve learned—through decades of research and experience—is that it’s the most foundational and impactful work a leader can do.

This makes our approach unique. While traditional development efforts aim to fill the toolbelt of a leader, this workshop focuses on upgrading the person wearing the toolbelt. We believe that tools are only as effective as the consciousness of the person using them. A wise leader with fewer tools will outperform a reactive leader with an overflowing toolbox.

So, our first objective isn’t to give you more tools. It’s to help you see yourself differently. We want to introduce you to aspects of your internal world that may have remained hidden—your assumptions, emotional patterns, ways of relating to others, and how you show up when the stakes are high. This is what we mean when we say we’re introducing you to your Being Side.

Once you see it, you can start to shift it.

And that shift—quiet and internal at first—has the potential to transform not only how you lead, but how others experience your leadership. It changes the tone you set, the culture you cultivate, and the impact you leave.

That’s the true heart of transformational leadership. And that’s the core objective of this workshop.

What Will Be Achieved

Elevating the Sophistication of Leadership

The world that leaders operate in today is vastly more complex than the one they entered years—or even months—ago. We are living in a VUCA environment: volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. Navigating this world requires more than functional competence or tactical execution. It requires a higher level of leadership sophistication.

This workshop exists to help leaders begin elevating the sophistication of their leadership—not through external strategies, but by upgrading the internal operating system from which all leadership behaviors and decisions arise.

Leadership sophistication is not about being more polished or more charismatic. It’s about increasing one’s internal capacity to lead wisely through uncertainty, to stay grounded in the face of pressure, and to influence others from a place of authenticity and clarity. Sophisticated leaders are not reactive—they are responsive. They don’t simply manage tasks—they shape systems. And they aren’t driven by ego—they are anchored in purpose.

This kind of leadership cannot be downloaded in a day or copied from a playbook. It must be developed from the inside out. And that is what this workshop initiates.

Introducing a New Lens for Leadership Growth

At the core of this workshop is a new way of seeing leadership—not just as a role or set of actions, but as a reflection of one’s inner world. This shift in perspective allows participants to move away from an over-reliance on the Doing Side of leadership (tools, tips, techniques) and begin exploring the Being Side—their character, mindset, emotional patterns, and sense of identity.

When we say this workshop helps participants elevate the sophistication of their leadership, we mean that it initiates a process of internal refinement—of growing into a leader who is not only more capable, but more conscious, more centered, and more impactful.

This transformation begins with three foundational insights.

The Key Ideas We Will Introduce

This workshop is designed to awaken leaders to three fundamental realities that will form the basis for all further growth:

The quality and sophistication of one’s “being” can be evaluated and developed.

Leadership is not just a matter of personality or innate talent. It is a developmental journey. And there are levels—higher and lower altitudes—of being that directly impact how we lead.

Leaders’ “being” varies significantly from person to person.

Some operate with a reactive, fear-based internal world. Others operate with clarity, empathy, and purpose. These differences often explain far more about leadership effectiveness than differences in skills or intelligence.

Transformational leadership growth only becomes possible when we awaken to the current quality of our being—and commit to elevating it.

The moment we begin to see ourselves clearly, we open the door to real change. Not just cosmetic change, but deep, identity-level transformation.

By understanding these core ideas and reflecting on how they apply to their own leadership, participants will initiate a new kind of developmental journey—one that is not about doing more, but about becoming more.

A Framework for Ongoing Growth

One of the most important achievements of this workshop is the establishment of a conceptual framework that participants can carry forward well beyond the session itself. This framework provides a new vocabulary and set of lenses for understanding:

The two sides of leadership: Doing and Being

The altitude or sophistication of one’s inner world

How one’s internal operating system influences external impact

The difference between reactive and creative ways of leading

The signs of elevation vs. stagnation in leadership development

Rather than simply introducing new content, the workshop offers a new structure for making sense of the content they’ve already absorbed in their leadership careers. It helps leaders reframe past experiences, re-evaluate current practices, and reimagine what future growth could look like.

This scaffolding will be referenced throughout the rest of the leadership development program—but it all starts here.

Expanding Internal Capacity to Lead in a VUCA World

The reason we elevate the sophistication of our leadership is because the challenges we face demand it.

In today’s world, leaders must:

Operate in highly dynamic environments where certainty is rare and change is constant

Engage with diverse stakeholders with competing needs, priorities, and worldviews

Navigate systemic complexity where decisions have cascading consequences

Lead with ethical clarity and long-term vision in the face of short-term pressures

Foster cultures of inclusion, trust, and resilience in teams stretched thin

These demands cannot be met with a checklist or a script. They require the ability to hold paradox, tolerate ambiguity, stay emotionally regulated under stress, and lead from conviction rather than compliance.

This workshop sets the foundation for developing those inner capacities. It begins the work of helping leaders:

See beyond symptoms to systems

Operate from values rather than ego

Create trust through presence and authenticity

Balance long-term vision with short-term action

Inspire others without controlling them

These are all hallmarks of elevated leadership sophistication—and they begin with shifts in the Being Side.

The Role of Experiential Learning

While the core learning of the workshop is conceptual, it is brought to life through direct experience. Participants will not passively consume ideas—they will actively engage with them.

To deepen learning and promote insight, participants will:

Explore leadership case studies that highlight how leaders with different levels of Being Side sophistication navigate challenge and complexity

Participate in interactive exercises that surface their current patterns and internal frameworks

Reflect in small groups and individually to increase awareness of how their own leadership identity has been shaped

Articulate aspirations for the kind of leader they want to become—and what might be holding them back

These experiences are not designed to “fix” anything, but to reveal and initiate. They help make visible the invisible elements of leadership—opening the door to future change.

Preparing for the Broader Leadership Journey

This workshop is the gateway into a larger leadership development experience. It is designed to open participants to the kind of growth that future workshops will support and build upon.

By the end of this session, participants will have:

A strong conceptual foundation for how leadership growth works

An introduction to the Being Side and how it affects everything they do

A framework and shared language for growth

A new orientation toward leadership as a developmental journey

Everything that follows in the broader program—skills, tools, strategies—will land more deeply and be applied more effectively because of the internal work that begins here.

A Different Kind of Achievement

Unlike traditional leadership development programs, the achievements of this workshop aren’t measured by what you can check off a list. They are measured by how you begin to see, think, and relate differently.

The outcomes are subtler—but far more powerful:

A new level of self-awareness

A stronger sense of ownership over one’s growth

An expanded view of what leadership is really about

A quiet shift in how participants carry themselves—less reactive, more grounded

The spark of a new identity as an elevating leader

These are not abstract achievements. They are the first signs of transformational growth.

That is what this workshop achieves.

How Participants Will Benefit

While the concepts introduced in this workshop are powerful in theory, their true value lies in how they affect the lived experience of leadership. The benefits that participants will gain extend well beyond intellectual insight—they are developmental, behavioral, relational, and organizational. And they begin at the level of the individual.

At its core, this workshop offers leaders a rare opportunity: the chance to pause, reflect, and examine who they are becoming. In the rush of responsibilities, deadlines, and performance expectations, leaders are rarely given the time or space to explore the inner world that shapes every external result. This workshop creates that space—and the benefits of stepping into it are profound.

A New Level of Self-Awareness

One of the most immediate benefits participants will experience is a deeper understanding of themselves. They will begin to uncover the internal drivers behind their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors—many of which have previously operated below the surface.

This self-awareness is not surface-level reflection. It is the kind of insight that helps leaders recognize:

Why they respond to pressure the way they do

What triggers their defensiveness, anxiety, or withdrawal

How their current mindsets either expand or limit their leadership potential

What kind of emotional environment they create for those around them

This level of self-clarity is the beginning of wisdom. Once leaders see themselves with new eyes, they can begin to make conscious choices about how they want to show up, rather than defaulting to old patterns.

Emotional Regulation and Presence

With greater awareness comes greater emotional regulation. Participants will begin to recognize how much of their leadership impact is influenced not by what they say or do, but by the energy and presence they bring into the room.

This workshop will help leaders:

Stay more centered under pressure

Navigate emotionally charged situations with steadiness

Shift from reactivity to intentionality

Project calm, confidence, and clarity—even in complexity

As leaders develop this kind of grounded presence, they become a source of stability and trust for others. They are no longer just managing others—they are modeling the kind of composure that invites others to rise.

Internal Clarity and Alignment

Another benefit participants will gain is a deeper connection to their values, purpose, and identity as a leader. This alignment between internal beliefs and external behaviors is what gives rise to authenticity—the quality most often associated with trusted, respected leaders.

When leaders operate from alignment, they:

Lead with conviction, not confusion

Make decisions with greater confidence and integrity

Build cultures rooted in clarity and coherence

Inspire others not just through words, but through who they are

This workshop will help participants begin cultivating that internal alignment—a benefit that pays dividends in every area of leadership.

A Raised Ceiling for Leadership Impact

While the focus of this workshop is on individual transformation, that transformation is never isolated. Leaders operate in systems, and their level of being sets the tone and ceiling for the teams and organizations they lead.

As participants begin elevating their Being Side, they naturally raise the collective potential of those around them. They foster healthier dynamics, model greater humility and courage, and create the psychological safety necessary for innovation and collaboration. Their growth unlocks the growth of others.

In this way, one of the greatest benefits participants experience is the realization that their personal development is not just about them. It’s about what becomes possible when they bring a more evolved, conscious version of themselves into the spaces they lead.

Stronger Relationships and Interpersonal Navigation

Another layer of benefit emerges as participants begin applying what they’ve discovered about themselves to their interactions with others. As they develop more empathy, patience, and self-regulation, they become better equipped to:

Navigate conflict constructively

Engage in difficult conversations with courage and grace

Tune into the emotional tone of others

Lead diverse personalities with flexibility and compassion

These relational shifts don’t come from mastering techniques—they come from becoming someone who leads from understanding rather than ego. And that’s what this workshop begins to develop.

Greater Readiness for Future Development

Perhaps most importantly, this workshop prepares participants to get more out of everything that follows. It is not a standalone experience—it is the foundation for a larger, deeper journey of leadership elevation.

The self-awareness, language, and mindset shifts introduced here create a context that will:

Accelerate the learning and application of future tools and strategies

Anchor later content in deeper personal insight

Enable more honest, productive reflection in future sessions

Foster a continuous growth orientation that extends beyond the program

In other words, this workshop helps leaders become better learners, better listeners, and better developers of themselves and others. It establishes a mindset of curiosity and self-leadership that magnifies the impact of future growth efforts.

Becoming the Kind of Leader Others Want to Follow

Ultimately, the greatest benefit of this workshop is not a new skill or idea. It’s a new trajectory.

Participants will begin to shift—not just in how they lead, but in who they are being while they lead. They will sense themselves growing in maturity, in discernment, and in personal power. They will carry themselves differently, relate differently, decide differently.

They will become the kind of leaders others trust—not because of their title, but because of their presence. Not because of their control, but because of their clarity. Not because of what they know, but because of who they are.

This is not only personally rewarding—it is professionally transformative.

A New Path Forward

In many ways, this workshop is unlike any leadership program you’ve experienced.

It won’t give you a checklist.

It won’t load you with information.

It won’t flatter you with surface-level praise.

Instead, it will invite you to do something far more powerful:

To look inward.

To reflect deeply.

To examine how your internal world shapes your external impact.

And to begin the lifelong process of elevating who you are.

That is the true heart of transformational leadership.

And that is the core objective of this workshop.

The History of Elevated Leadership

For decades, the field of leadership research has been guided by one central question:

What do leaders need to do to be effective?

This question, while useful in many ways, has shaped the field in a way that is ultimately short-sighted and problematic. It has led scholars, practitioners, and organizations alike to focus almost exclusively on the Doing Side of leadership—on observable behaviors, competencies, and techniques. As a result, leadership development has become largely an exercise in skill acquisition and behavior modification. Leaders are often handed checklists, toolkits, and models and told, “Do these things, and you’ll be effective.”

To be fair, this Doing Side emphasis has produced important insights. It has given us a language for communication, delegation, feedback, emotional intelligence, team dynamics, and more. These are helpful and necessary components of leadership. But they only tell part of the story. And when we treat them as the whole story, we severely limit the depth and durability of leadership growth.

Why? Because most leadership challenges are not the result of a lack of knowledge or skill.

They are the result of something deeper—something harder to see, but far more powerful.

They are the result of limitations in the Being Side of the leader.

We’ve all seen this in action. A leader knows what to do—they’ve read the books, taken the courses, maybe even delivered the training themselves. But in moments of stress, ambiguity, or interpersonal tension, they default to defensiveness, avoidance, control, or ego. Despite their knowledge, they behave in ways that erode trust, stifle collaboration, and undermine the very outcomes they intend to create.

This isn’t a Doing Side issue. It’s a Being Side issue. And yet, for much of leadership development history, this internal dimension has been ignored, underemphasized, or misunderstood.

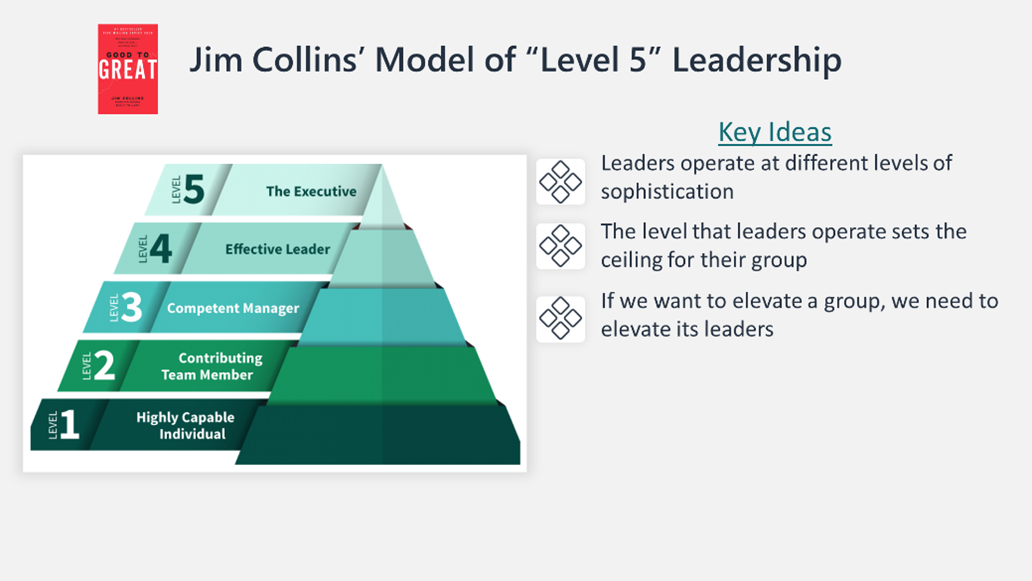

Fortunately, there have been key voices who have helped shift the conversation. One of the most influential has been Jim Collins.

In his seminal work, Good to Great, Collins introduced the concept of Level 5 Leadership—a groundbreaking idea that has helped reframe how we understand leadership effectiveness. His research found that the most successful and enduring organizations were not led by the most charismatic, bold, or visionary individuals. Rather, they were led by leaders who combined deep personal humility with fierce professional will. These leaders didn’t seek the spotlight. They didn’t make themselves the hero of the story. They were committed to something larger than themselves—and that commitment shaped everything they did.

What Collins brought into focus was this:

Leaders operate at different levels of sophistication.

And that sophistication—the maturity, mindset, and internal grounding of the leader—sets the ceiling for the organization they lead.

This was a profound insight. It helped us understand that leadership is not just a set of actions, but a way of being. It helped us see that organizational outcomes are not just a reflection of strategy, but of the inner world of those at the top. And most importantly, it helped shine a light on a truth that had long gone unspoken: If you want to elevate an organization, you must first elevate its leaders.

But while Collins illuminated the destination—Level 5 Leadership—he left us without a map.

He described what Level 5 Leaders look like, how they behave, and what kind of results they produce. But he did not provide a clear or actionable pathway for how to develop them. He identified the qualities, but not the process. As a result, many organizations have admired the concept of Level 5 Leadership without knowing how to cultivate it within their own leaders.

That is the gap this workshop—and this leadership development program—seeks to fill.

We start where most leadership research has stopped: not with what leaders do, but with who they are being. We seek to move beyond superficial improvements and toward the internal transformation that elevates leadership at its core. And in doing so, we honor the truth that Collins helped surface—while going deeper into the developmental journey he left unexplored.

The time has come to move past the era of checklist leadership. The challenges we face today demand more than competence. They demand character. They demand not just more tools, but a more evolved tool bearer. And that evolution begins by returning to the question too often overlooked:

Who are you being as a leader?

The Current Position of Elevated Leadership

It has been nearly 25 years since Jim Collins introduced the concept of Level 5 Leadership to the world. At the time, it was a groundbreaking insight: that the most effective leaders—those who build organizations of lasting greatness—operate with a level of humility, inner strength, and purpose that sets them apart. They don’t just execute well. They lead from a higher level of maturity, clarity, and internal grounding.

Collins gave us a vision of what exceptional leadership looks like. But in the years since, the question has remained: How do we help leaders become Level 5 Leaders?

Today, we are in a much stronger position to answer that question than we were 25 years ago. While Collins’s work created a compelling destination, the past two decades have brought tremendous advancements in our understanding of how to get there. Several key movements have converged to illuminate what it takes to truly elevate a leader’s internal operating system.

The Rise of Neuroscience

Perhaps the most significant development has been the explosion of neuroscience research. In fact, there has been more published neuroscience research in the past 15 years than in all of recorded history prior. This research has transformed our understanding of how the brain works, how behaviors are shaped, how people learn, and—critically—how people change.

We now know that a leader’s inner world—their mindsets, emotional regulation, and reactivity—are not fixed traits. They are patterns of thought and behavior that can be reshaped through conscious effort and deliberate practice. Through the lens of neuroplasticity, we understand that even long-standing mental habits can be rewired. This insight has made it possible to move leadership development away from a surface-level focus on behavior and toward deep, systemic change.

Put simply, neuroscience has shown us that leaders can upgrade their internal operating systems. And when they do, they lead with greater calm, clarity, and courage—hallmarks of Level 5 sophistication.

Insights from Trauma and Nervous System Healing

In parallel with neuroscience, research into trauma and nervous system regulation has shed light on how unresolved stress, fear, and emotional wounds impact how leaders show up. What we’ve learned is that many leadership derailers—micromanagement, defensiveness, emotional volatility, avoidance—aren’t just personality quirks. They are nervous system responses.

When leaders are unaware of how their nervous system is operating—when they are hijacked by fight, flight, or freeze responses—they lose access to the very qualities that define sophisticated leadership. But when they begin to recognize and regulate these patterns, they gain access to more grounded, open, and creative states of being.

This body of research has given us language, tools, and practices for helping leaders operate from a more integrated and resourced internal state. It’s not about perfection—it’s about presence. And leaders who cultivate presence become dramatically more effective, especially in high-stakes or emotionally charged situations.

The Influence of the Mindfulness Movement

Another important influence has been the global mindfulness movement. While mindfulness practices have existed for centuries, their application to leadership is relatively recent. What we’ve discovered is that mindfulness isn’t just about stress reduction—it’s about consciousness.

Mindfulness trains us to observe rather than react, to pause rather than push, and to lead from intention rather than impulse. As this movement has gained traction, it has helped normalize the idea that great leadership is not just about what we do—it’s about how we show up.

This shift has reinforced a powerful truth: People don’t just follow leaders because of their credentials, competence, or communication skills. They follow leaders because of their being—the energy, presence, and emotional tone they bring into every interaction.

Where We Are Now

Taken together, these movements have advanced our understanding of what it takes to develop leaders with Level 5 character and capacity. We now have the insights, the science, and the practices to help leaders grow in ways that were once considered intangible or out of reach.

We do know how to develop Level 5 Leaders.

But here’s the challenge: Very few people know how to do it. And even fewer are doing it.

Most leadership development programs are still anchored in the traditional Doing Side approach—teaching skills, behaviors, and techniques without ever addressing the deeper structures that determine whether those tools will stick. As a result, even well-intentioned development efforts often fall short. They scratch the surface, but they don’t shift the system.

Meanwhile, the world is demanding more from leaders than ever before. Burnout is rising. Trust in leadership is eroding. Employees are disengaged and disillusioned. The pace of change is accelerating, and complexity is growing. These are not challenges that can be solved by working harder or applying a new framework. They are challenges that demand a different kind of leadership—a more elevated, intentional, and grounded presence.

That is the kind of leadership this program is designed to cultivate.

We are at a tipping point. For the first time, we have both the need and the know-how to fundamentally transform how leadership development is approached. And that’s where this workshop fits in.

This program is not simply aligned with the latest science—it is shaped by it. It bridges the gap between what we now understand about human development and what leaders need to thrive in today’s world. It provides a structured, evidence-informed pathway to help leaders elevate their Being Side, increase their sophistication, and become the kind of leaders others want to follow.

In short: This program represents the cutting edge of leadership development.

And it’s not just timely—it’s urgently needed.

The Future Outlook of Elevated Leadership

As we look to the future of leadership development, one thing is increasingly clear: the organizations and individuals who embrace Being Side development today will be the ones best equipped to lead tomorrow.

The insights, frameworks, and practices presented in this workshop are not just innovative—they represent the next evolution of leadership development. And for those who engage with them now, they offer a significant and sustainable competitive advantage.

In the years ahead, the ability to navigate uncertainty, complexity, and change will only become more important. The pace of disruption is not slowing down. The expectations placed on leaders—by their teams, stakeholders, and society at large—are intensifying. And the capacity to lead with humility, groundedness, and presence will separate the merely competent from the truly transformational.

That is why the approach introduced in this workshop matters so much. Leaders who elevate the sophistication of their Being Side will stand out. They will develop the ability to:

Make better decisions under pressure

Build higher-trust, higher-performing teams

Foster cultures of safety, innovation, and belonging

Lead adaptively through complexity and ambiguity

Inspire others not through charisma or control, but through clarity and character

These qualities are not trends or fads. They are the foundation of enduring leadership excellence.

And when an organization commits to developing these qualities at scale—when it invests in helping many of its leaders elevate their Being Side—it raises the ceiling for what the organization as a whole can achieve. Elevated leaders build elevated teams. Elevated teams build elevated cultures. And elevated cultures create durable advantage in increasingly competitive markets.

This is not a hypothetical idea—it is a strategic imperative.

Organizations that prioritize this kind of leadership development will not only outperform competitors in the short term; they will be positioned to thrive in the long term. They will attract and retain the best talent. They will adapt more fluidly to change. They will operate with deeper alignment, purpose, and integrity. And they will earn the trust of their stakeholders in a way that cannot be manufactured through branding or external messaging.

As more leaders begin to awaken to the importance of their Being Side—and as more organizations begin to recognize the limits of traditional, Doing Side-focused development—we anticipate a broader shift in the field of leadership development. This program sits at the forefront of that shift. It represents what’s next.

For those willing to engage in this deeper work, the benefits are not just personal. They are cultural. They are organizational. And they are transformational.

This is the future of leadership development. And the future belongs to those who are ready to lead from a more elevated place.

Case Study

Microsoft: An Elevated Leader Elevates the Organization

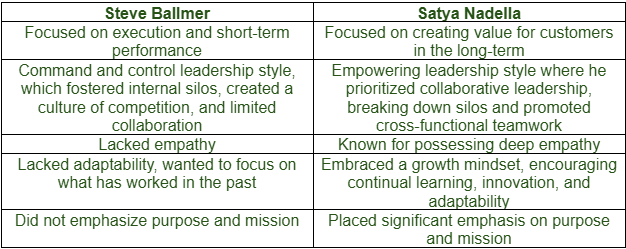

When Satya Nadella became CEO of Microsoft in 2014, the company was still a technology giant—but it had lost its cultural vitality and its innovative edge. Internally, Microsoft was fractured by silos, status-driven leadership, and a culture of fear and defensiveness. Externally, it was seen as lagging behind more agile and forward-thinking competitors like Apple, Google, and Amazon.

While the company’s leadership had traditionally focused on performance and execution—the Doing Side of leadership—it became clear that what Microsoft needed was not just new strategy or tools, but a new kind of leader. One who would lead from a more grounded, humble, and forward-looking Being Side.

That leader was Satya Nadella.

Elevating the Ceiling: A Shift in Leadership Sophistication

Satya Nadella’s appointment marked a turning point in Microsoft’s history—not just in leadership style, but in leadership altitude. Compared to his predecessor, Steve Ballmer, Nadella brought a fundamentally different presence to the CEO role. While Ballmer was known for his intensity, command-and-control leadership, and sharp competitiveness, Nadella entered the role with quiet humility, emotional intelligence, and a focus on learning.

From the beginning, Nadella led less from ego and more from purpose. He centered his leadership around empathy, collaboration, and curiosity—qualities that may not appear on traditional leadership competency models but are central to the Being Side. His presence alone began to raise the ceiling for how leadership was understood and enacted across Microsoft.

And the results were extraordinary.

Since Nadella took the helm:

Microsoft’s market capitalization has grown from around $300 billion in 2014 to over $2.8 trillion by early 2024, making it one of the most valuable companies in the world.

The company has reestablished itself as a leader in cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and enterprise software.

Microsoft has consistently ranked as one of the best places to work and one of the most admired companies globally.

These outcomes were not achieved through surface-level changes or operational tweaks. They came because the Being Side of leadership was elevated, starting with Nadella himself.

Creating a Culture that Elevates Being

Nadella’s influence didn’t stop with his personal leadership style. He brought a philosophy and cultural vision that reached deep into the soul of the company. Rather than reinforcing a Doing Side culture that prized certainty, perfection, and hierarchy, he pushed for a culture rooted in openness, self-reflection, and growth.

The most notable manifestation of this shift was his championing of a growth mindset—inspired by Carol Dweck’s research. Nadella emphasized that Microsoft needed to move from a “know-it-all” culture to a “learn-it-all” culture. This wasn’t just a clever phrase. It was a profound reorientation of the company’s Being Side.

Instead of defining leadership by how much people knew or how right they were, Nadella encouraged leaders to lead with curiosity, to listen more, to challenge their assumptions, and to welcome feedback. He normalized vulnerability and learning—not only among engineers and product teams, but among senior leaders.

He also placed empathy at the center of Microsoft’s leadership identity. As he famously said, “The learn-it-all does better than the know-it-all,” and, “Empathy makes you a better innovator.” These statements reflect a deeper truth: that leadership effectiveness is not just about technical intelligence, but about emotional and relational intelligence—the core elements of Being.

Nadella’s emphasis on empathy wasn’t theoretical. It was rooted in his lived experience, including raising a child with severe disabilities. This life experience shaped how he understood leadership—as service, not dominance; as listening, not asserting. That authenticity resonated throughout the organization.

As a result, leaders across Microsoft began to evolve—not because they were trained to use new tools, but because they were invited to become different people. They were encouraged to grow in humility, openness, patience, presence, and long-term thinking.

Microsoft’s performance didn’t improve in spite of this Being Side shift. It improved because of it.

A New Standard for Leadership

Satya Nadella’s leadership journey at Microsoft is one of the clearest modern examples of how elevating the Being Side of a leader can transform an entire organization.

He didn’t begin by demanding different behaviors—he began by being different. And that difference in who he was led to changes in how people related, collaborated, made decisions, and took ownership across the company.

The traditional approach to leadership development—focused almost entirely on knowledge, skills, and doing—could never have catalyzed such a transformation. What Microsoft needed was not just better leaders, but more sophisticated ones.

And Nadella gave them exactly that.

What This Case Study Demonstrates

This story brings to life many of the core insights of this workshop:

The leader sets the ceiling: Nadella’s personal presence elevated the possibilities of everyone around him.

Being Side matters more than Doing Side: Culture, innovation, and trust were transformed not by new checklists, but by new mindsets and ways of being.

Elevated leaders create elevated organizations: Microsoft’s return to industry leadership wasn’t just a business turnaround—it was a human one.

Satya Nadella didn’t just turn around a company. He redefined what leadership could look like in the 21st century.

And in doing so, he showed the world what’s possible when a leader leads from the inside out.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Leadership Levels

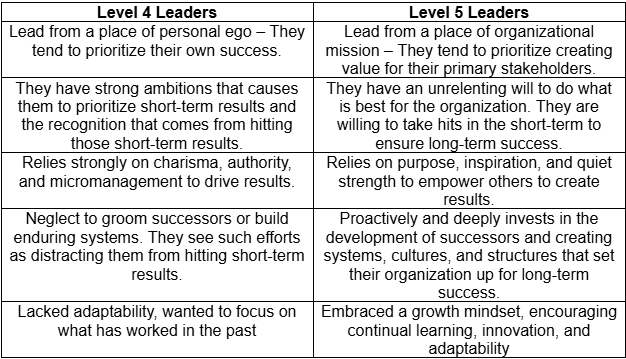

Module 1 introduces participants to Jim Collins’s Level 5 Leadership Framework—a research-backed model that identifies the leadership behaviors and internal characteristics necessary to drive enduring organizational greatness. Drawing from Collins’s book Good to Great, this module emphasizes that Level 5 leaders are not just high performers—they are fundamentally different in how they think, lead, and serve.

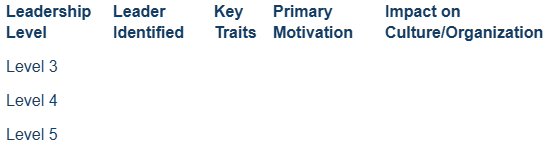

The module begins by outlining the five levels of leadership:

Level 1: Highly Capable Individual – Known for technical competence and personal productivity.

Level 2: Contributing Team Member – Focuses on collaboration and group objectives.

Level 3: Competent Manager – Operates through formal leadership and is accountable for team performance.

Level 4: Effective Leader – Inspires others through strategic vision, charisma, and results.

Level 5: Executive Leader – Blends deep humility with fierce resolve to build organizations that endure.

The framework illustrates a progression of leadership sophistication, culminating in Level 5, where influence is not driven by ego or authority but by legacy, culture, and purpose.

Most leaders operate at Level 3 or Level 4, and while these leaders can be effective, their impact is often limited by short-term thinking, self-promotion, or lack of depth. In contrast, Level 5 leaders elevate the people, systems, and culture around them. They build high-performing, resilient organizations by focusing on long-term outcomes, psychological safety, and sustainable success.

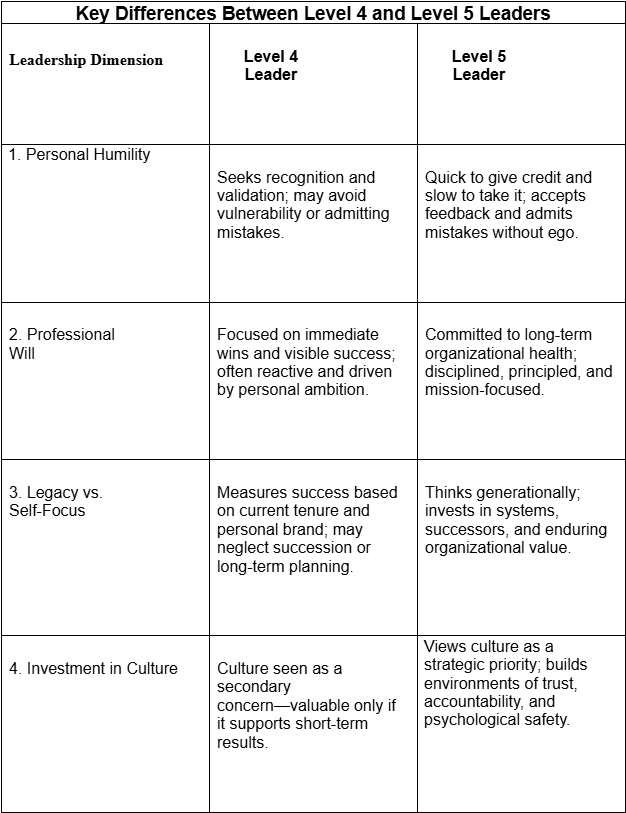

Participants are introduced to the four key contrasts between Level 4 and Level 5 leaders:

Personal Humility vs. ego and the need for recognition

Professional Will vs. performance-driven ambition

Legacy Focus vs. short-term wins and personal branding

Culture Investment vs. deprioritizing culture in favor of immediate results

Through comparative analysis and case studies—including Darwin Smith of Kimberly-Clark and Alan Mulally of Ford—participants see how Level 5 leaders shift focus from self to service, from performance to purpose, and from image to impact.

The module also highlights the organizational outcomes associated with Level 5 leadership: increased employee engagement, stronger values-based cultures, better long-term performance, and higher resilience through disruption.

One of the module’s key messages is that Level 5 leadership is rare but learnable. Collins originally questioned how such leaders could be developed, but modern leadership research has since revealed that the shift from Level 4 to Level 5 is not about learning new techniques—it’s about upgrading one’s internal operating system. This includes changing one’s mindset, refining one’s purpose, and developing deeper emotional maturity.

This workshop initiates that transformation. Leaders are invited to reflect on their current level of leadership, identify growth opportunities, and begin developing the internal foundation necessary for Level 5 influence. It’s not just about what leaders do—it’s about who they are becoming.

The session closes with small group exercises that help participants articulate which aspects of Level 5 leadership they most want to develop, fostering introspection, shared insight, and connection—hallmarks of the journey ahead.

Chapter 2: Lesson of Leadership

Module 2 of the leadership development program introduces a foundational insight: leadership is not defined by position or title, but by influence. The module begins by redefining leadership through a practical and focused lens: Leadership is the use of power and influence to direct others to goal achievement. With this definition, it becomes clear that effective leadership is not dependent on authority, but on the leader’s ability to shape behavior and outcomes through trust and engagement.

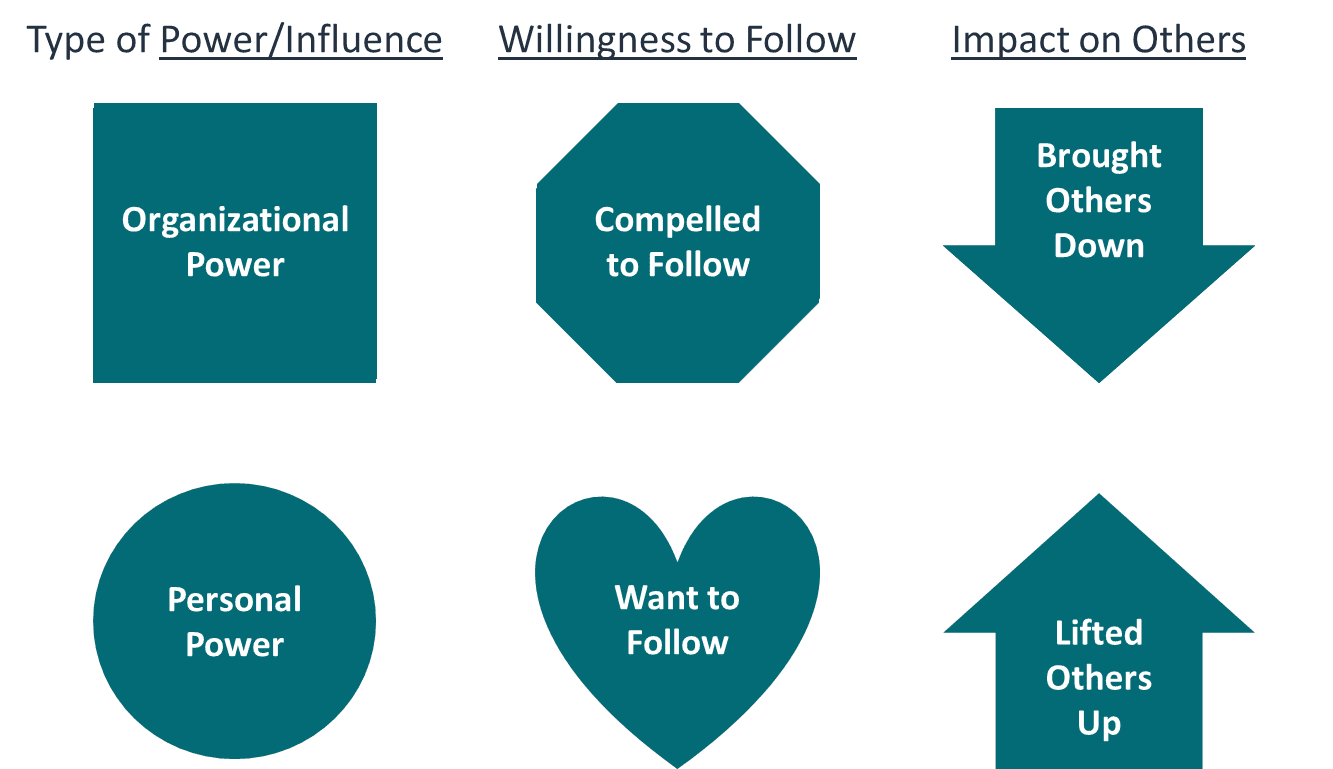

To simplify what great leadership requires, the module narrows the conversation to two essential attributes: power and influence. Power is defined as the potential to influence others’ behavior, while influence is about securing others’ voluntary commitment to shared goals. Importantly, not all power is created equal—and the quality of a leader’s impact depends on the type of power they use.

Participants are introduced to the distinction between organizational power and personal power.

Organizational power stems from formal position and includes three forms:

Authoritative power – based on hierarchical authority and directive-based leadership.

Reward power – based on offering incentives to drive compliance.

Coercive power – based on using threats or punishment to enforce behavior.

While organizational power can ensure compliance and is sometimes necessary, it can also create dependency, disengagement, and a transactional leadership culture. Leaders who rely too heavily on this form of power risk undermining long-term trust, creativity, and team cohesion.

Personal power, by contrast, is earned rather than granted. It comes from who a leader is—not the title they hold. It includes:

Referent power – derived from trust, respect, and the strength of relationships.

Expert power – derived from competence, insight, and experience.

Leaders who cultivate personal power build loyalty, unlock discretionary effort, and foster resilient, purpose-driven teams. While personal power is more difficult to earn and does not guarantee immediate results, it fosters lasting influence and followership that isn’t tied to positional authority.

Through exercises and examples—including a case study of NBA coach Phil Jackson—participants reflect on how different sources of power operate in practice. Jackson’s example demonstrates how leaders can inspire high performance through personalized leadership and relational trust, not just top-down direction.

The module culminates in what it names the #1 lesson of leadership:

“If you want to be an effective leader, you must become someone others want to follow.”

This lesson reframes leadership development as a process of personal growth, not positional advancement. It encourages participants to move away from relying on organizational power and toward cultivating personal power by developing character, trustworthiness, empathy, and expertise.

Participants are challenged to examine how they currently lead and what type of power they lean on most. The session closes by asking leaders to reflect on the importance of building strong relationships and invites them to begin the deeper work of becoming a leader who leads through influence, not authority.

Chapter 3: The Two Sides of Ourselves

Module 3 introduces a foundational framework for leadership development by distinguishing between two essential dimensions of every leader: the Doing Side and the Being Side. This distinction is key to understanding the source of leadership effectiveness and the root of most leadership struggles. While traditional development focuses heavily on skills, competencies, and execution (the Doing Side), this module makes the case that the Being Side—our mindset, emotional regulation, consciousness, and character—is the greater determinant of whether we become someone others truly want to follow.

The module begins by exploring examples of high-profile leaders who achieved notable success—such as Bobby Knight, Sam Bankman-Fried, and Ellen DeGeneres—yet were also surrounded by controversy. These examples reveal a critical insight: technical ability alone does not guarantee great leadership. These individuals had strong Doing Sides, but many of their struggles stemmed from limitations in their Being Side.

Participants are then introduced to the Doing/Being 2×2 Framework, which maps leaders across four quadrants:

Low Doing / Low Being – Individuals with low competency and low self-regulation. Research shows most people fall into this quadrant.

High Doing / Low Being – Highly capable leaders who lack the emotional maturity and mindset to lead effectively. This is where most organizational leaders operate today.

Low Doing / High Being – Individuals who may not excel technically but possess deep wisdom, character, and emotional stability (e.g., monks).

High Doing / High Being – The rarest and most impactful leaders. These are Level 5 leaders—those who combine high performance with deep personal presence, character, and wisdom.

Research from developmental psychology and organizational leadership reveals that the majority of leadership issues stem from deficiencies in the Being Side, not the Doing Side. Emotional reactivity, ego-driven behavior, and poor team dynamics often trace back to internal limitations, not technical skill gaps.

The module makes a compelling case that the Being Side is the differentiator of great leadership. While the Doing Side enables leaders to achieve results, it is the Being Side that allows them to inspire trust, foster culture, and create lasting impact. Characteristics like humility, emotional intelligence, authenticity, and courage are not trained through traditional skill-based development—they are cultivated through intentional self-work.

The conclusion is clear: most leadership development focuses on the wrong side. To truly grow into transformational leaders—those who embody Level 5 leadership—we must shift our focus inward. This program is designed to help participants do exactly that: develop the Being Side so they can lead not just with excellence, but with presence, purpose, and sustainable influence.

As the module closes, participants are invited to begin reflecting on their current location in the 2×2 framework and to prepare for a deeper exploration of the Being Side in upcoming sessions.

Chapter 4: Common Leadership Issues

Module 4 examines three of the most persistent and damaging leadership issues—micromanagement, emotional intelligence deficiencies, and conflict avoidance—and challenges the prevailing notion that these are primarily skill-based problems. Instead, this module makes a compelling case that these issues stem from deeper, internal dynamics within a leader’s “Being Side,” such as insecurity, fear, emotional reactivity, and self-protective tendencies.

Reframing Leadership Challenges

Traditionally, leadership development programs focus on external behaviors and technical skills (the “Doing Side”). However, this module reframes leadership struggles as symptoms of the “Being Side”—the internal operating system that governs how a leader thinks, feels, perceives, and regulates themselves. Using this lens, participants are encouraged to look beneath the surface and consider the inner roots of their leadership patterns.

Micromanagement as a Self-Protective Strategy

Micromanagement is presented not as a simple failure to delegate, but as a manifestation of personal insecurity. Leaders may micromanage due to:

A lack of trust in others

A fear of failure or mistakes

Perfectionism

Career-stage insecurity

A desire for credit or recognition

While often well-intended, micromanagement is ultimately self-protective—it soothes the leader’s own anxiety and need for control. But it comes at a cost: reduced innovation, lower trust, slower decision-making, and higher employee disengagement and turnover. Leaders are invited to examine the short-term emotional relief micromanagement offers versus its long-term damage to performance and culture.

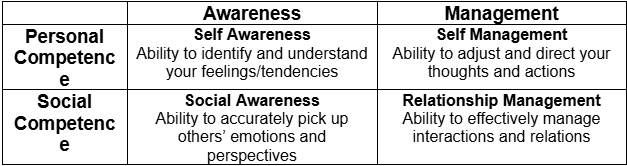

Emotional Intelligence and the Limits of Skill-Based Training

The module introduces a comprehensive emotional intelligence (EI) model that includes:

Self-awareness

Self-management

Social awareness

Relationship management

Rather than viewing EI as a trainable skill set, the module emphasizes that EI is fundamentally tied to brain functioning and emotional maturity. Leaders with low EI often struggle with defensiveness, reactivity, poor communication, and an inability to manage emotions in high-stakes situations. These issues are rooted in an overactive threat response (e.g., amygdala hijack) and underdeveloped self-regulatory capacity—not a lack of knowledge.

The takeaway: Without addressing their internal wiring, leaders will continue to fall short—even after attending traditional EI trainings. Real change requires personal transformation, not just new communication techniques.

Conflict Avoidance and the Fear of Discomfort

Conflict avoidance is framed as another common leadership dysfunction rooted in the Being Side. Leaders avoid difficult conversations to protect themselves from discomfort, rejection, or emotional intensity. Whether it’s underperformance, interpersonal tension, or resistance to change, avoidance undermines accountability, trust, and psychological safety.

This self-protective strategy provides short-term relief but leads to long-term dysfunction: unclear expectations, resentment, and cultural erosion.

Shifting from Self-Protection to Self-Leadership

Throughout the module, participants are challenged to examine their leadership struggles not as surface-level missteps, but as reflections of deeper patterns. They explore how their own insecurities and internal responses drive behavior—and how these behaviors, though understandable, can limit their impact and erode trust.

By shifting their focus inward, leaders can begin to address the true source of their challenges. Developing the Being Side—through greater self-awareness, emotional regulation, and courage—becomes the path toward more empowered, sustainable leadership.

This prepares participants for the next step in the program: understanding what exemplary leadership looks like and how it flows from internal transformation, not just external polish.

Chapter 5: Exemplary Leadership

Module 5 marks a pivotal shift in the leadership development journey—from diagnosing poor leadership to defining and dissecting what exemplary leadership truly looks like. This module introduces and explores Level 5 Leadership in action, offering participants tangible case studies, distinguishing characteristics, and interactive comparisons that highlight the Being Side of transformative leadership.

The module begins with an in-depth case study of Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, contrasting his leadership style with his predecessor, Steve Ballmer. While Ballmer led with short-term execution, control, and ego, Nadella embraced empowerment, humility, collaboration, and a long-term value-creation mindset. Under Nadella, Microsoft’s market value skyrocketed, internal culture shifted toward inclusion and innovation, and trust increased across all levels of the organization. This case helps participants see that what separates exemplary leaders isn’t talent or technical expertise—it’s their Being Side: who they are, how they lead, and the internal operating system from which they operate.

From there, the module invites participants to identify and explore key traits of exemplary leaders, including:

Humility – Putting mission above ego and welcoming feedback.

Resilience – Staying grounded through adversity.

Patience – Valuing long-term impact over immediate wins.

Vulnerability – Creating trust through authenticity.

Courage – Doing what’s right even when it’s difficult.

Empathy – Leading with emotional intelligence and care.

These traits are not techniques; they are expressions of a leader’s Being. The module emphasizes that the most impactful leadership doesn’t stem from authority or charisma, but from maturity, clarity, and purpose.

Next, the module explores the differences between Level 4 and Level 5 leaders—especially in how they lead from ego vs. mission, chase short-term results vs. long-term outcomes, control vs. empower, and focus on personal success vs. organizational sustainability. Participants reflect on these contrasts and consider how they’ve seen them play out in real-world leaders and organizations.

The second case study features Indra Nooyi, former CEO of PepsiCo, who embodies Level 5 leadership through her long-term vision, social responsibility, and human-centered approach. Her leadership transformed PepsiCo’s strategy, culture, and brand—again highlighting how Level 5 leaders operate from a deep internal foundation of values, humility, and conviction.

The module closes with a practical, scenario-based group exercise in which participants contrast how a Level 4 vs. Level 5 leader might respond to common leadership challenges—such as public mistakes, missed deadlines, or disengaged high performers. Through these comparisons, participants begin to internalize the subtle but powerful differences in mindset and approach that define exemplary leadership.

Finally, participants are reminded that Level 5 leadership is rare—only about 8% of leaders embody it consistently—but it is learnable. The effectiveness of exemplary leaders stems not from their Doing Side, but from their Being Side. The remainder of the program will focus on helping participants upgrade that internal operating system, so they too can grow into Level 5 leaders who inspire, empower, and leave a lasting legacy.

Chapter 6: What is Our Being Side?

Before leaders can meaningfully grow, they must understand what exactly they’re growing. Module 6 answers that question by unpacking the concept of the Being Side—the internal foundation of leadership that drives how individuals think, feel, and respond in every moment. While the Doing Side reflects visible skills and actions, the Being Side reflects the invisible operating system that governs those behaviors.

To help leaders visualize this, the module introduces the metaphor of a computer’s internal operating system. Just as a computer’s software determines what it can do, a leader’s internal programming influences how they make decisions, handle stress, build relationships, and show up under pressure. Much of this programming runs automatically and outside of conscious awareness—but it has a profound impact on leadership effectiveness.

The module distinguishes between two dominant modes of internal programming:

Self-Protective Wiring – Designed to minimize discomfort, fear, or threat. These patterns often originate from past experiences and can lead to defensiveness, control, perfectionism, or avoidance.

Value-Creating Wiring – Oriented toward growth, learning, and long-term impact. Leaders with this wiring remain open, grounded, and intentional—even in high-stakes or uncertain environments.

Participants learn that most leadership struggles—like micromanagement, reactivity, or conflict avoidance—don’t stem from a lack of knowledge or intention. They stem from an internal operating system that is overly protective and reactive. To lead more effectively, the wiring itself must be upgraded.

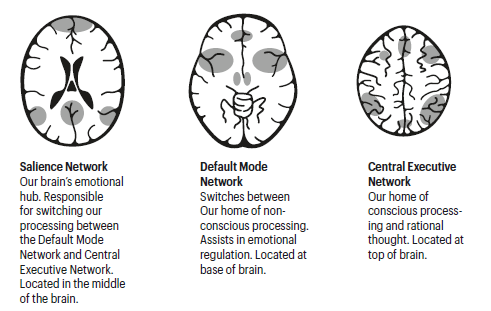

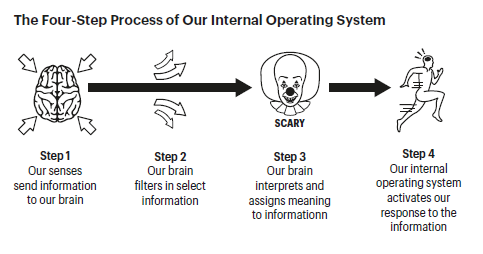

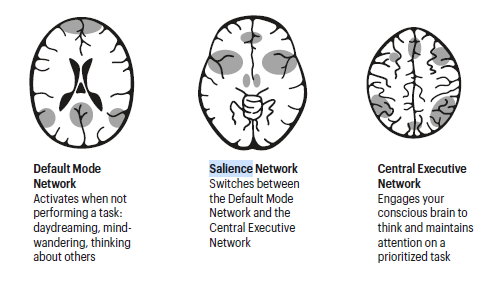

The neuroscience behind this process is also introduced. Leaders explore how their nervous system acts as the gateway between external triggers and internal meaning-making. The module explains how the brain’s automatic filtering and interpretation of experiences—particularly through the salience network and default mode network—shapes emotional and behavioral responses. These subconscious filters prioritize safety, often at the cost of authenticity, connection, or courage.

To make these insights personal, participants engage in the If-Then Exercise:

If [triggering event], then [habitual response].

This activity reveals self-protective patterns in real time (e.g., “If someone questions my decision, then I shut down”). Participants are then invited to reflect on whether these patterns are aligned with the kind of leader they want to become.

The module introduces the idea that transformation begins with awareness. While the internal operating system may be automatic, it is not unchangeable. With the right insight and intention, leaders can rewire self-protective patterns into more value-creating ones.

The case study of Brené Brown helps illustrate this concept. Once closed off to vulnerability, Brown intentionally rewired her internal system to embrace openness and connection—choices that ultimately elevated her leadership and impact.

Module 6 closes with a key definition:

Our Being Side is the degree to which our internal operating system is wired for value creation rather than self-protection.

With this foundation laid, the next module will explore how leaders make meaning of the world around them—and how that meaning-making process can be either a barrier or a bridge to transformational leadership.

Chapter 7: Meaning Making

Module 7 explores a foundational yet often overlooked driver of leadership effectiveness: the automatic and subconscious process of meaning making. As participants continue deepening their understanding of the Being Side of leadership, this module reveals that one of the primary functions of our internal operating system is to assign meaning—quickly and unconsciously—to the experiences, challenges, and feedback we encounter.

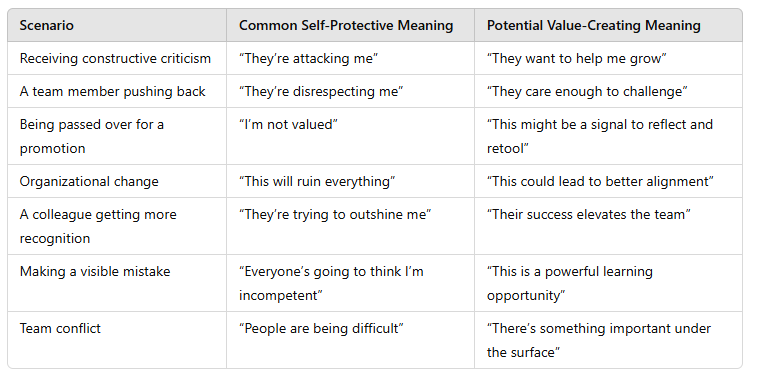

The central insight is that not all meaning making is created equal. Two people can experience the same situation but walk away with completely different interpretations—and those interpretations will shape their emotions, behaviors, relationships, and leadership outcomes. While meaning making happens automatically, it is far from fixed. Leaders can become more aware of their meaning-making tendencies and intentionally upgrade them over time.

The module introduces two distinct patterns of meaning making:

Self-Protective Meaning Making is rooted in fear, insecurity, or the desire to maintain control. It often leads leaders to interpret challenges—such as failure, criticism, or conflict—as threats. This keeps them safe in the short term but can cause long-term stagnation, avoidance, and relational distance.

Value-Creating Meaning Making interprets those same situations as opportunities for learning, connection, or growth. While this approach may feel riskier, it leads to greater adaptability, innovation, and influence over time.

Participants reflect on how they interpret a variety of leadership experiences—such as failure, vulnerability, stillness, conflict, and feedback—and examine the downstream effects of those interpretations. Through a small-group exercise, they explore how meaning making shapes behavior, team dynamics, and culture, and they begin to recognize that better meaning making = better leadership.

To make this concrete, the module focuses on one of the most defining areas of meaning making: failure. Two common interpretations of failure are examined:

Failure as a reflection of self-worth (self-protective): This mindset leads to fear, avoidance, and rigid behavior.

Failure as a catalyst for growth (value-creating): This fosters resilience, learning, and innovation.

Real-world examples bring these concepts to life:

Satya Nadella modeled value-creating meaning making when Microsoft’s chatbot failed publicly. Instead of blaming the team, he encouraged them to “keep pushing,” reinforcing psychological safety and a growth-oriented culture.

Thomas Edison and Sara Blakely are cited as leaders who embraced failure as a sign of experimentation and progress—not inadequacy.

The module connects meaning making to four broader organizational outcomes:

Employee Engagement: Leaders who reframe disengagement as a signal for curiosity rather than defiance foster trust and ownership.

Innovation: Leaders who interpret failure as learning foster experimentation; those who see it as incompetence create fear.

Organizational Agility: Leaders who view change as a threat resist it; those who see it as opportunity adapt and evolve.

Learning Culture: Leaders who treat knowledge gaps as growth opportunities (vs. weaknesses) cultivate high-performing teams.

In conclusion, Module 7 reinforces that Level 5 leaders consistently make meaning in value-creating ways. This does not mean ignoring discomfort—it means interpreting discomfort as a signal for growth, not danger. As leaders upgrade their meaning making, they unlock the capacity to lead with deeper trust, clarity, and long-term impact.

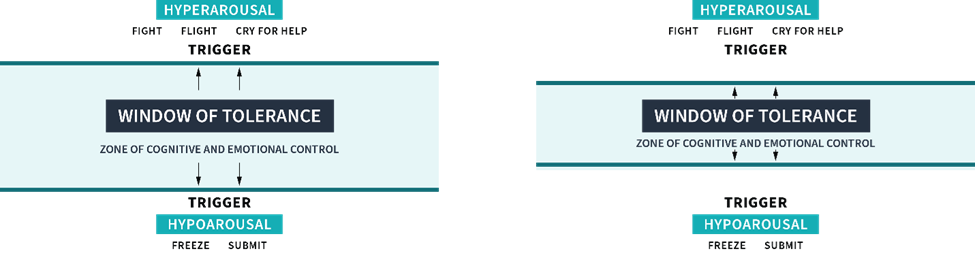

Chapter 8: Window of Tolerance

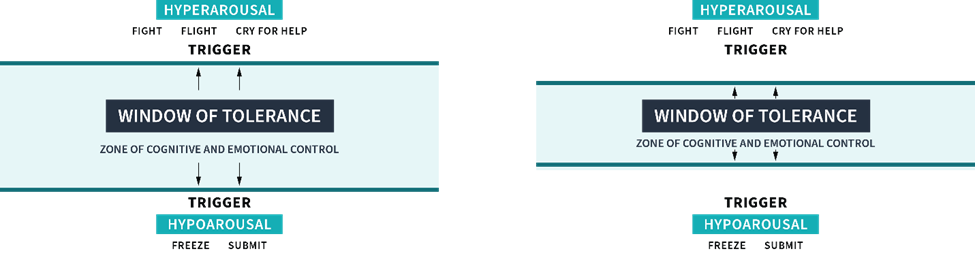

Module 8 continues the exploration of the Being Side of leadership by introducing a powerful concept from neuroscience and psychology: the window of tolerance. Originally coined by Dr. Dan Siegel, this concept refers to the range within which individuals can remain emotionally regulated, cognitively flexible, and behaviorally effective when encountering stress, adversity, or discomfort. In a leadership context, a wide window of tolerance allows individuals to lead with clarity and composure even under pressure—while a narrow window leads to dysregulation, reactivity, and diminished effectiveness.

The module positions the window of tolerance as a practical lens for evaluating a leader’s internal operating system. Leaders programmed for value creation are more likely to stay within their window, tolerating short-term discomfort for long-term impact. In contrast, leaders with self-protective wiring often fall outside their window more easily, defaulting to reactive or avoidant behaviors.

At a neurological level, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a key role in regulating this window through two branches:

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activates the fight-or-flight response, leading to hyperarousal—emotional reactivity, impulsiveness, and rigidity.

The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) facilitates calm and recovery. However, excessive activation can lead to hypoarousal—emotional numbness, disengagement, and shutdown.

Leaders functioning outside their window—whether in hyper- or hypoarousal—struggle to access their executive functioning, emotional intelligence, and decision-making capacity. The result is reactive leadership, impaired communication, and decreased team trust.

Participants reflect on their own responses to stress across various contexts—failure, conflict, vulnerability, stillness—and assess how wide or narrow their window of tolerance may be. The module outlines common signs of a narrow window, such as defensiveness, indecisiveness, and a need for control, versus indicators of a wide window, such as adaptability, emotional regulation, and thoughtful risk-taking.

To illustrate these dynamics, the module contrasts two leaders:

Howard Schultz (Starbucks) exemplifies wide-window leadership. Amid a financial crisis, he remained emotionally grounded and made bold, values-driven decisions—like temporarily closing 7,100 stores to retrain staff—prioritizing long-term culture over short-term profit.

Doug McMillon (Walmart) demonstrates a narrower window. In the face of rising digital competition, his early reluctance to make bold e-commerce investments reflected discomfort with uncertainty and high-stakes risk, resulting in slower innovation and cultural hesitancy.

From these examples, five leadership lessons emerge:

Internal regulation shapes external outcomes—regulated leaders make better decisions under pressure.

A leader’s window shapes team culture—their composure fosters psychological safety and agility.

Risk tolerance depends on emotional regulation—wider windows enable strategic risk-taking.

Window width influences communication and trust—grounded leaders communicate with clarity and inspire confidence.

A wide window supports sustainable leadership—avoiding burnout and maintaining consistency.

The module closes with a collaborative exercise where groups create a “Window Recovery Toolkit”—a set of practical tools for recognizing, regulating, and re-entering one’s window of tolerance. This reinforces the idea that the window is not fixed—it can be intentionally widened over time through reflection, self-regulation, and mindset shifts.

Looking ahead, the program will explore the root causes of narrow windows and self-protective programming, setting the stage for deeper transformation along the Being Side.

Chapter 9: Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Psychological Trauma

Module 9 introduces the first major disrupter of the Being Side: psychological trauma. This module makes a compelling case that trauma—especially unacknowledged or unresolved—can significantly distort a leader’s internal operating system and, in turn, undermine their ability to lead with emotional intelligence, trust, and long-term vision.

The module opens with research from the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, which found that roughly 70% of adults have experienced psychological trauma. The more trauma one experiences, the more likely they are to struggle with physical health, emotional regulation, behavioral issues, and reduced life potential. But the real insight is in why: trauma fundamentally rewires the nervous system toward self-protection rather than value creation.

Rather than define trauma by the event itself, the module reframes trauma as a neurological adaptation—a psychological wounding that occurs when an experience overwhelms the nervous system’s capacity to cope. This reframing helps explain why two people can experience the same event (e.g., combat, car crash, rejection), yet only one may carry lasting trauma. The difference lies in the body’s stress response system and its window of tolerance.

Using the concept of the window of tolerance, the module explores how trauma can either over-activate or suppress the nervous system’s emotional regulation capacity. When the stress is too much, the body takes drastic measures—either heightening alertness (hypervigilance) or disconnecting from feelings altogether (dissociation). Both adaptations serve survival in the moment, but they create lasting limitations in leadership contexts.

The module introduces three brain networks involved in meaning-making and behavior regulation:

The salience network detects emotional signals and threats.

The default mode network governs automatic, self-related, and social processing.

The central executive network oversees conscious, rational decision-making.

When trauma strikes, these networks become imbalanced. Hypervigilance occurs when the salience network becomes overactive and the default mode network underperforms—causing leaders to interpret even minor issues as major threats. Dissociation results when the default mode network overregulates, dulling emotional responses and cutting off access to feeling.

The case study of “Tom”—a former military leader and EMT—brings these concepts to life. While his hypervigilant wiring served him well in combat and emergency response roles, it led to micromanagement, risk avoidance, and a lack of trust in his corporate leadership position. His inability to recalibrate his nervous system ultimately limited his leadership effectiveness and led to his early exit from the organization.

The module closes by connecting trauma to emotional intelligence (EI), which is often considered one of the most essential leadership capabilities. Trauma-induced wiring—whether hypervigilant or dissociated—directly impairs the key components of EI:

Hypervigilance hinders self-management and social awareness.

Dissociation hinders self-awareness and relationship management.

The takeaway is clear: unhealed trauma limits a leader’s Being Side altitude, which in turn constrains their capacity to be emotionally intelligent and influential. To develop into Level 5 leaders, individuals must be willing to acknowledge and, if necessary, heal the unseen wounds of the past that are quietly shaping their leadership today.

Chapter 10: Disrupter of our Being Side #1: Our Current Culture

Module 10 explores how current cultural environments—particularly within teams and organizations—profoundly shape a leader’s and employee’s internal operating system, influencing whether they are wired for self-protection or value creation. While earlier modules explored individual-level disrupters (e.g., trauma), this module focuses on environmental conditions that can activate or suppress the Being Side of leadership.

At the core of this exploration is a powerful insight: the culture we are in either reinforces fear and competition or fosters safety and cooperation—and this directly impacts our neurological wiring, emotional regulation, and leadership effectiveness.

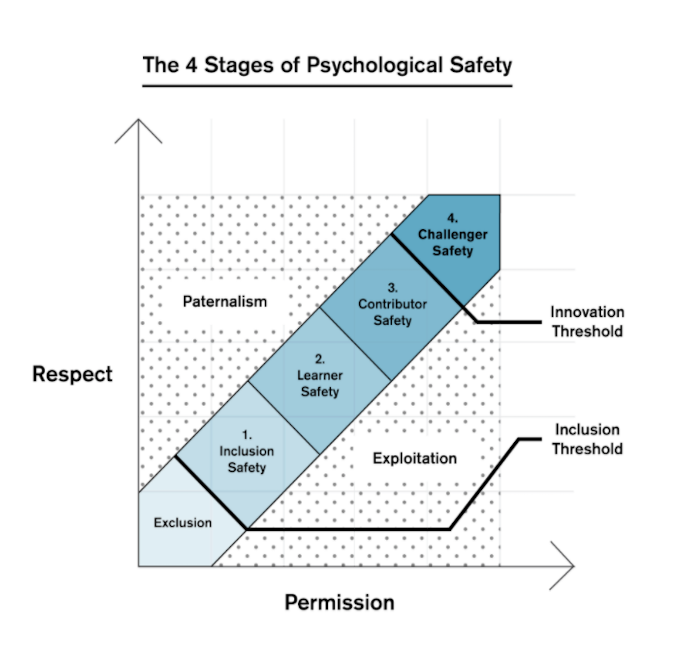

The session begins with an assessment of psychological safety, using a short seven-item survey that measures how safe participants feel to speak up, take risks, and be themselves within their teams. Scores offer insight into whether a culture supports value creation or conditions individuals for guarded, self-protective behavior.