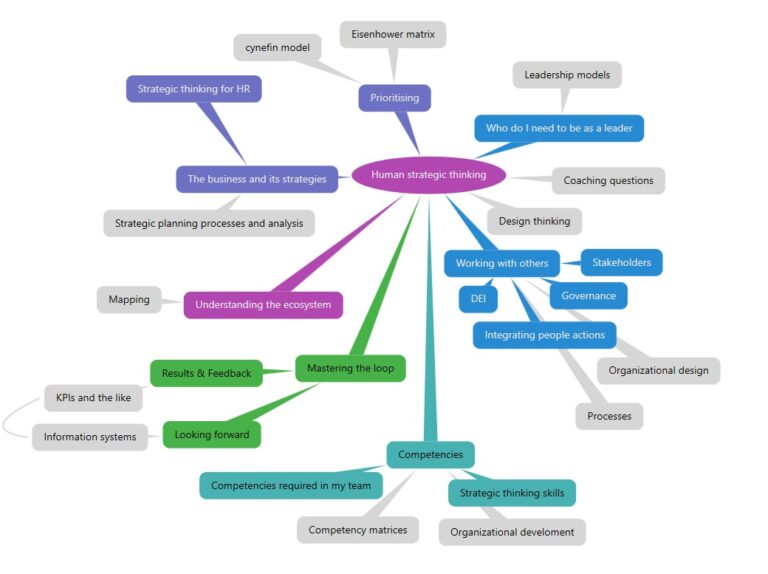

Human Strategic Thinking – WDP1 (Understanding the Landscape)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Human Strategic Thinking is provided by Ms. Petitpas Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Ms. Petitpas is a Certified Learning Provider (CLP) with Appleton Greene. She has over 30 years of experience in consulting, coaching, and training CEOs, executives, and management teams. She specializes in strategic thinking and planning, organizational development, human resources, and leadership. She is passionate about accompanying leaders in realizing and achieving their unique contributions, integrating the business and people aspects to create their desired impact on all stakeholders.

She has industry experience in the following sectors: Technology, Business Services, Biomedical, Consultancy, Manufacturing and Healthcare. She has worked with organizations with core activities in the following countries: Canada, United States, Mexico, and France, and more frequently within the following cities: Montreal, QC; Laval, QC; Québec, QC; Toronto, ON.

Her achievements include eight years as Founder of Polychrome, where she advises and coaches business owners and leaders to transform their organization and create value for all stakeholders based on their values and aspirations, capitalizing on the strengths of their teams; co-author of a book about strategic thinking, and is a regular contributor to LaReferenceRH.

Strategic thinking, management experience, and coaching have enabled her clients to reach significant insights and their organizations to evolve significantly and become more resilient, prosperous, and overall better as customer and employee experience providers.

To request further information about Ms. Petitpas through Appleton Greene, please Click Here.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

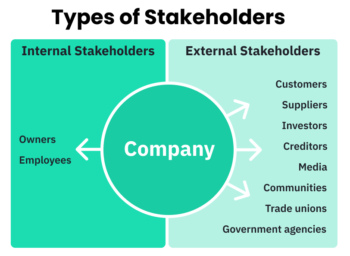

HR and people management, in general, do not exist in a vacuum. They can both support the implementation of strategies defined by others and be an impetus for change and value creation. To do so, it is necessary to understand the organization’s business. This first step will allow participants to gain further clarity on their circumstances, the different types of strategies, and the value drivers of significant importance, beyond their understanding of their industry. They will consider the various ecosystems, both internal and external, that strategic plans and initiatives cater to and depend upon for successful implementation.

Objectives

01. Changing Perspective: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. The Evolution of Strategy: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. What is Strategic Thinking?: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. What do we mean by focusing on the Human Element?: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. About Strategic Plans: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Who is my Organization?: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. My Organization’s Industry: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Value Drivers: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Stakeholders: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Ecosystems: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Changing Perspective: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. The Evolution of Strategy: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. What is Strategic Thinking?: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. What do we mean by focusing on the Human Element?: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. About Strategic Plans: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Who is my Organization?: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. My Organization’s Industry: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Value Drivers: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

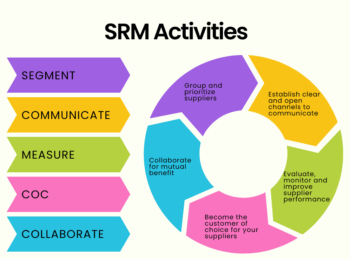

09. Stakeholders: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Ecosystems: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Changing Perspective.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse The Evolution of Strategy.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse What is Strategic Thinking?.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse What do we mean by focusing on the Human Element?.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze About Strategic Plans.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Who is my Organization?.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse My Organization’s Industry.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Value Drivers.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Stakeholders.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Ecosystems.

Introduction

The capacity to think strategically is crucial not just for top executives but also for leaders at all levels, as well as those responsible for implementing strategic plans. Strategic thinking enables organizations to navigate uncertainties, anticipate changes, and adapt to evolving business landscapes, ensuring long-term sustainability and competitive advantage.

Strategic thinking is not limited to understanding the market or competitors; it involves a comprehensive understanding of the internal and external factors that impact the organization. This includes recognizing the interplay between the business’s operational aspects, the human elements within the organization, and the broader economic, social, and technological environment. By integrating these perspectives, leaders can make informed decisions that align with the organization’s goals and drive value creation.

HR and People Management in Strategic Thinking

HR and people management functions play a vital role in the strategic success of an organization. Traditionally viewed as support functions, these areas are increasingly recognized as critical drivers of strategic initiatives. HR professionals and people leaders are uniquely positioned to influence the strategic direction of the organization by aligning human capital with business objectives.

HR’s role extends beyond the recruitment and management of talent; it involves fostering a culture that supports strategic goals, driving engagement, and ensuring that employees are motivated and equipped to contribute to the organization’s success. In this context, understanding the business landscape is essential for HR professionals, as it allows them to tailor their strategies to meet the organization’s needs and challenges.

The integration of HR into strategic thinking processes ensures that people-related factors are considered in every decision. This includes understanding how changes in the business environment may impact employee morale, productivity, and engagement, and how the organization can leverage its human capital to achieve its strategic goals.

Evolving Role of HR and People Management: Historically, HR and people management functions were often perceived as administrative or support roles, focused primarily on recruitment, payroll, and compliance. However, in today’s dynamic business environment, this perception has shifted significantly. Organizations now recognize that HR and people management are not just support functions but are central to driving strategic initiatives and ensuring the overall success of the organization.

The shift from a transactional to a strategic role means that HR professionals and people leaders are no longer merely custodians of policies and procedures. Instead, they are seen as key players in shaping the organization’s strategic direction. By aligning human capital with business objectives, HR ensures that the organization has the right talent, in the right roles, at the right time, all working towards common goals. This alignment is critical in achieving sustainable competitive advantage.

Strategic Alignment of Human Capital: The strategic alignment of human capital involves a deep understanding of the organization’s goals and the translation of these goals into people-related strategies and actions. HR professionals must work closely with other leaders to ensure that the organization’s human resources are effectively utilized to support strategic priorities. This requires a proactive approach to workforce planning, talent management, and employee development.

For instance, if an organization is pursuing a growth strategy that involves expanding into new markets, HR needs to ensure that the organization has the necessary skills and capabilities to succeed in those markets. This may involve recruiting new talent with specialized expertise, developing existing employees through targeted training programs, and fostering a culture of innovation and adaptability.

HR plays a critical role in succession planning, ensuring that there is a pipeline of talent ready to step into key roles as the organization grows or as leadership transitions occur. By strategically managing human capital, HR helps to create a resilient organization that can adapt to change and achieve its long-term objectives.

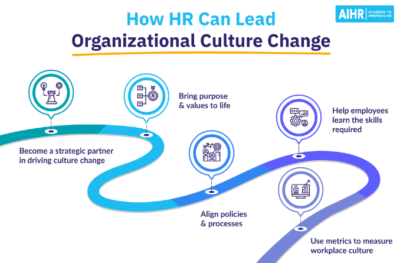

Fostering a Culture that Supports Strategic Goals: Culture is a powerful force within any organization, and HR is the primary steward of this culture. A well-aligned organizational culture can be a significant driver of strategic success, while a misaligned culture can be a major obstacle. HR’s role in fostering a culture that supports strategic goals is multifaceted and involves several key activities.

Firstly, HR is responsible for defining and communicating the organization’s values, mission, and vision, ensuring that these are not just statements on paper but are embedded in the everyday behavior of employees. This involves creating programs and initiatives that reinforce the desired culture, such as recognition and reward systems that align with the organization’s strategic objectives.

Secondly, HR must ensure that leadership at all levels is aligned with the strategic goals and is actively promoting the desired culture. This includes providing leadership development programs that equip managers with the skills needed to lead in a way that supports the organization’s strategy. It also involves holding leaders accountable for their role in fostering the culture, through performance management and feedback mechanisms.

Finally, HR must continuously monitor and assess the culture to ensure that it remains aligned with the organization’s strategic direction. This may involve conducting employee engagement surveys, analyzing turnover data, and facilitating discussions around culture at all levels of the organization. By taking a proactive approach to culture management, HR helps to create an environment where employees are motivated, engaged, and aligned with the organization’s strategic goals.

Driving Employee Engagement and Motivation: Employee engagement and motivation are critical factors in the successful execution of strategic initiatives. Engaged employees are more likely to be productive, innovative, and committed to the organization’s goals. HR plays a central role in driving engagement by creating an environment where employees feel valued, supported, and connected to the organization’s mission.

One way HR drives engagement is through the design and implementation of comprehensive employee value propositions (EVPs). An EVP encompasses everything an organization offers its employees in exchange for their skills and commitment, including compensation, benefits, career development opportunities, and a positive work environment. A well-crafted EVP can attract top talent and keep current employees motivated and engaged.

HR is responsible for designing performance management systems that align individual goals with organizational objectives. By setting clear expectations, providing regular feedback, and recognizing and rewarding achievements, HR helps to ensure that employees are focused on the right priorities and are motivated to contribute to the organization’s success.

HR also plays a crucial role in fostering a sense of purpose among employees. People are more likely to be engaged and motivated when they understand how their work contributes to the broader goals of the organization. HR can facilitate this understanding by ensuring that communication around the organization’s strategy is clear, consistent, and meaningful. This involves not only top-down communication from leaders but also creating opportunities for employees to provide input and feedback on the strategy.

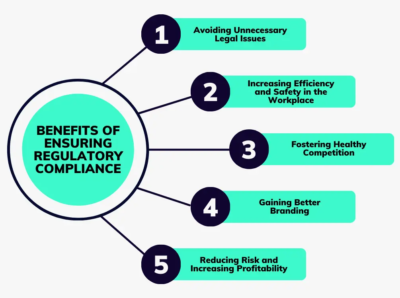

Understanding the Business Landscape: For HR to effectively contribute to strategic success, it is essential that HR professionals have a deep understanding of the business landscape in which their organization operates. This understanding includes both the internal and external factors that impact the organization, such as market trends, competitive dynamics, regulatory changes, and technological advancements.

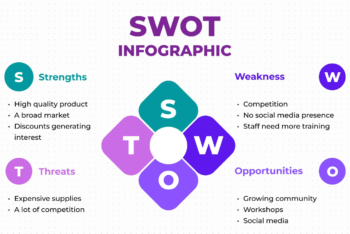

Internally, HR needs to be aware of the organization’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT analysis). This knowledge allows HR to tailor its strategies to support the organization’s strategic objectives. For example, if an organization is facing a talent shortage in a critical area, HR can develop targeted recruitment and development programs to address this gap.

Externally, HR must stay informed about trends and developments that could impact the organization’s human capital needs. For example, the rise of remote work and the increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI) in HR processes are significant trends that HR must navigate. By understanding these external factors, HR can proactively adjust its strategies to ensure that the organization remains competitive and resilient.

Additionally, understanding the business landscape involves recognizing the interplay between the organization’s strategic goals and the broader ecosystem. This includes considering how changes in the external environment, such as economic downturns or shifts in consumer behavior, might impact employee morale, productivity, and engagement. HR must be able to anticipate these impacts and develop strategies to mitigate potential risks.

Integration of HR into Strategic Thinking Processes: The integration of HR into strategic thinking processes ensures that people-related factors are considered in every strategic decision. This integration is critical because the success of any strategy ultimately depends on the people who implement it. HR’s involvement in strategic planning allows for a more holistic approach, where human capital is not an afterthought but a central consideration.

One way HR contributes to strategic thinking is by providing data and insights that inform decision-making. Through workforce analytics, HR can identify trends and patterns related to employee performance, engagement, turnover, and other key metrics. This data-driven approach enables HR to provide evidence-based recommendations that support strategic objectives.

HR’s integration into strategic thinking also involves scenario planning and risk management. By considering various scenarios and their potential impact on the workforce, HR can help the organization prepare for different outcomes and ensure that it has the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances. This might include developing contingency plans for talent shortages, restructuring efforts, or changes in labor laws.

HR’s involvement in strategic thinking ensures that the organization’s human capital strategy is aligned with its business strategy. This alignment is crucial for ensuring that the organization has the necessary skills, capabilities, and culture to achieve its strategic goals. It also helps to ensure that employees are engaged and motivated to contribute to the organization’s success, which is essential for effective strategy execution.

Finally, HR plays a key role in change management, which is an integral part of strategic thinking. Successful implementation of strategic initiatives often requires significant changes in processes, systems, and behaviors. HR is responsible for managing these changes in a way that minimizes disruption and maximizes buy-in from employees. This involves clear communication, training, and support to help employees navigate the transition and embrace new ways of working.

Understanding the Business Landscape: A Holistic Approach

Understanding the business landscape is the first step in strategic thinking. This involves gaining a comprehensive view of the organization’s internal and external environments. Internally, leaders must understand the organization’s strengths, weaknesses, capabilities, and culture. Externally, they must be aware of market trends, competitive forces, regulatory changes, and other external factors that could impact the organization.

A holistic approach to understanding the business landscape includes:

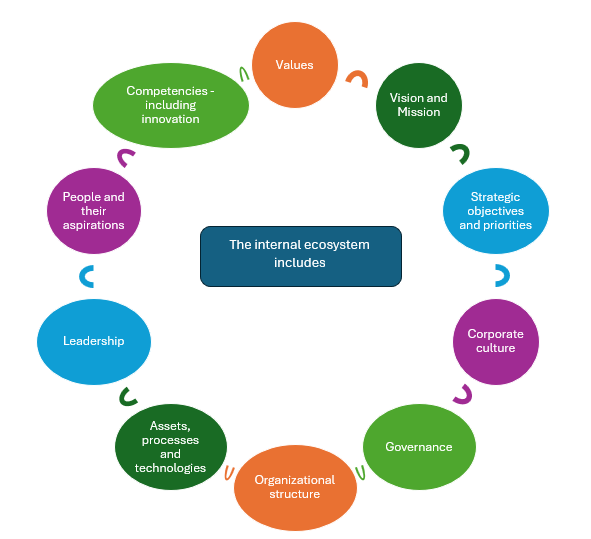

• Internal Ecosystem: This refers to the organization’s internal dynamics, including its structure, culture, processes, and resources. Leaders must understand how these elements interact and how they contribute to the organization’s overall strategy. This also involves recognizing potential internal barriers to strategic success, such as misaligned goals, poor communication, or resistance to change.

• External Ecosystem: The external ecosystem encompasses the broader environment in which the organization operates. This includes the market, competitors, regulatory environment, technological advancements, and socio-economic trends. Understanding these factors is crucial for identifying opportunities and threats and for shaping strategies that are responsive to the external environment.

The Internal Ecosystem: Understanding the Organization from Within

The internal ecosystem of an organization comprises the various elements that exist within its boundaries. These include the organization’s structure, culture, processes, and resources, all of which play a vital role in shaping the organization’s strategic capabilities and constraints.

• Organizational Structure: The structure of an organization determines how its various components are arranged and how they interact with each other. This includes the hierarchy of authority, the distribution of responsibilities, and the flow of information. A well-designed structure can enhance efficiency, facilitate communication, and enable quick decision-making. However, a poorly designed structure can lead to silos, bottlenecks, and misaligned goals, all of which can impede strategic success. Leaders must assess whether the current organizational structure supports or hinders the execution of strategy and make adjustments as necessary.

• Organizational Culture: Culture is the set of shared values, beliefs, and behaviors that define how people within the organization interact with each other and approach their work. It significantly influences employee motivation, engagement, and productivity. A culture that fosters innovation, collaboration, and a commitment to excellence can be a powerful driver of strategic success. Conversely, a culture characterized by resistance to change, lack of accountability, or poor communication can undermine strategic initiatives. Understanding the existing culture and its alignment with the organization’s strategic goals is essential for effective strategy formulation and implementation.

• Processes and Workflows: The processes and workflows within an organization define how work gets done. These include everything from product development and service delivery to customer support and internal communication. Efficient processes that are aligned with strategic goals can improve productivity and customer satisfaction, while inefficient processes can lead to delays, errors, and wasted resources. Leaders need to evaluate the effectiveness of their organization’s processes and determine whether they are conducive to achieving strategic objectives or whether they require reengineering.

• Resources and Capabilities: An organization’s resources include its human capital, financial assets, technology, intellectual property, and physical infrastructure. Capabilities refer to the organization’s ability to deploy these resources effectively to achieve strategic goals. Leaders must assess whether the organization has the necessary resources and capabilities to execute its strategy successfully. This involves identifying areas where additional investment may be needed, such as in technology upgrades, employee training, or process improvements. It also requires recognizing any resource constraints that could limit the organization’s ability to pursue certain strategic initiatives.

• Internal Barriers to Success: Recognizing potential internal barriers is a critical aspect of understanding the internal ecosystem. These barriers can include misaligned goals, where different departments or individuals pursue objectives that conflict with the overall strategy. Poor communication is another common barrier, leading to misunderstandings, duplicated efforts, or missed opportunities. Resistance to change, whether due to fear, uncertainty, or lack of trust in leadership, can also hinder the implementation of new strategies. Leaders must be vigilant in identifying and addressing these barriers to ensure that the organization’s internal ecosystem supports its strategic objectives.

The External Ecosystem: Navigating the Broader Environment

The external ecosystem encompasses the factors outside the organization that can impact its ability to achieve strategic goals. This includes market dynamics, competitive forces, regulatory environments, technological advancements, and broader socio-economic trends. Understanding these factors is crucial for identifying opportunities and threats, and for shaping strategies that are responsive to the external environment.

• Market Dynamics: Market dynamics refer to the forces that affect the supply and demand for products and services within an industry. These dynamics include customer preferences, market size, growth rates, and the competitive landscape. A deep understanding of market dynamics allows organizations to anticipate shifts in customer needs, identify emerging markets, and adjust their product or service offerings accordingly. For example, a company that understands a growing demand for sustainable products can develop new offerings that meet this demand, thereby gaining a competitive edge.

• Competitive Forces: Analyzing the competitive landscape involves understanding who the competitors are, what they offer, and how they position themselves in the market. This analysis can be guided by frameworks such as Porter’s Five Forces, which considers the threat of new entrants, the bargaining power of suppliers and buyers, the threat of substitute products, and the intensity of competitive rivalry. By understanding these forces, organizations can develop strategies that exploit their competitive advantages, such as differentiating their offerings, targeting underserved market segments, or leveraging economies of scale.

• Regulatory Environment: The regulatory environment consists of the laws, regulations, and policies that govern how organizations operate within a particular industry or region. Compliance with these regulations is essential to avoid legal penalties, financial losses, and reputational damage. However, regulations can also present opportunities. For instance, new environmental regulations may create demand for sustainable products, or tax incentives for research and development could encourage innovation. Leaders must stay informed about regulatory changes and assess their potential impact on the organization’s strategy.

• Technological Advancements: Technology is a major driver of change in today’s business environment. Technological advancements can create new opportunities for innovation, efficiency, and customer engagement, but they can also disrupt existing business models and render products or services obsolete. Organizations must continually monitor technological trends, such as the rise of artificial intelligence, automation, and digital transformation, and consider how these technologies could impact their industry. By staying ahead of technological developments, organizations can leverage new tools and capabilities to enhance their strategic position.

• Socio-Economic Trends: Socio-economic trends, such as demographic shifts, changes in consumer behavior, and economic cycles, can significantly impact the external ecosystem. For example, an aging population may increase demand for healthcare services, while economic downturns could lead to reduced consumer spending. Understanding these trends allows organizations to anticipate changes in the market and adjust their strategies accordingly. This might involve targeting new customer segments, diversifying revenue streams, or adopting more flexible business models.

• Globalization and Geopolitical Factors: In an increasingly globalized world, organizations must also consider the impact of international trade, global supply chains, and geopolitical factors. Globalization offers opportunities for expanding into new markets, sourcing from a global supplier base, and accessing diverse talent pools. However, it also introduces risks, such as trade barriers, currency fluctuations, and political instability. Leaders must understand the global context in which they operate and develop strategies that mitigate these risks while capitalizing on global opportunities.

Integrating the Internal and External Ecosystems for Strategic Success

A holistic approach to understanding the business landscape requires integrating insights from both the internal and external ecosystems. This integration enables leaders to develop strategies that are not only realistic and achievable but also aligned with the organization’s capabilities and market conditions.

• SWOT Analysis: One effective tool for integrating internal and external insights is the SWOT analysis. This framework helps leaders identify the organization’s Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. Strengths and weaknesses are internal factors, while opportunities and threats are external. By conducting a SWOT analysis, leaders can develop strategies that leverage the organization’s strengths to capitalize on opportunities, while also addressing weaknesses and mitigating threats. For example, a company with strong technological capabilities (internal strength) might seize the opportunity to innovate in response to a market trend (external opportunity), while also addressing a weakness in its supply chain (internal weakness) to mitigate the threat of disruption (external threat).

• Strategic Fit: Another key concept in integrating the internal and external ecosystems is strategic fit. Strategic fit refers to the alignment between an organization’s internal capabilities and its external opportunities. Achieving strategic fit involves ensuring that the organization’s resources, culture, and processes are well-matched to the demands and opportunities of the external environment. When there is a strong strategic fit, the organization is more likely to achieve its goals and sustain competitive advantage. For example, a company with a strong culture of innovation and a skilled workforce may find a strategic fit in a rapidly evolving technology sector, where continuous innovation is necessary to stay competitive.

• Anticipating Challenges and Adjusting Strategies: By understanding both the internal and external ecosystems, leaders can anticipate potential challenges and make proactive adjustments to their strategies. This includes identifying early warning signals of changes in the external environment, such as new competitors entering the market, regulatory changes, or shifts in customer preferences. Internally, it involves monitoring key performance indicators (KPIs) and other metrics to assess whether the organization is on track to achieve its strategic objectives. If challenges arise, leaders can adjust their strategies by reallocating resources, changing priorities, or adopting new approaches to execution.

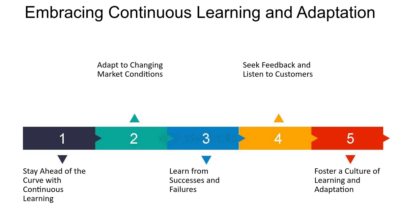

• Continuous Learning and Adaptation: The business landscape is dynamic, and successful organizations must be agile and adaptable. Continuous learning and adaptation are essential components of a holistic approach to understanding the business landscape. This involves regularly reviewing and updating the organization’s understanding of both internal and external factors, as well as being willing to pivot when necessary. Leaders should foster a culture of continuous improvement, where employees are encouraged to learn from successes and failures, share insights, and contribute to the ongoing refinement of the organization’s strategy.

The Strategic Role of Leaders in Navigating the Business Landscape

Leaders play a crucial role in navigating the business landscape. They are responsible for synthesizing information from both the internal and external ecosystems, making informed decisions, and guiding the organization towards its strategic goals. This requires a combination of analytical skills, creative thinking, and the ability to inspire and mobilize others.

• Visionary Leadership: Visionary leaders have the ability to see the big picture and articulate a compelling vision for the future. They understand the importance of the business landscape in shaping the organization’s long-term strategy and are skilled at identifying trends and opportunities that others may overlook. Visionary leaders inspire their teams to embrace change, take calculated risks, and pursue innovation in alignment with the organization’s strategic goals.

• Strategic Decision-Making: Effective strategic decision-making requires a deep understanding of both the internal and external ecosystems. Leaders must weigh the potential risks and benefits of different courses of action, considering how each decision will impact the organization’s ability to achieve its strategic objectives. This involves not only analyzing data but also applying intuition, experience, and judgment to make decisions that are both informed and forward-thinking.

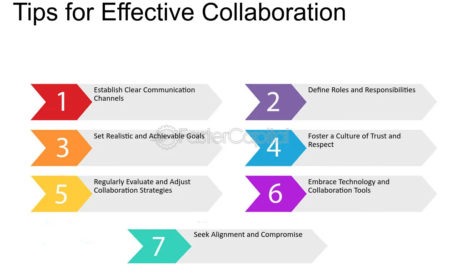

• Communication and Collaboration: Leaders must also be effective communicators and collaborators. They need to ensure that their understanding of the business landscape is shared across the organization and that employees at all levels are aligned with the strategic vision. This involves communicating the rationale behind strategic decisions, fostering collaboration across departments, and creating a sense of shared purpose. By doing so, leaders can build a strong organizational culture that supports strategic success.

• Adaptive Leadership: In a constantly changing business environment, adaptive leadership is critical. Adaptive leaders are flexible and resilient, able to adjust their strategies in response to new information or changing circumstances. They are also proactive in seeking out opportunities for growth and improvement, even in the face of uncertainty. Adaptive leaders recognize that the business landscape is not static, and they are prepared to evolve their approach as needed to ensure the organization’s continued success.

By understanding both the internal and external ecosystems, leaders can develop strategies that are realistic, achievable, and aligned with the organization’s capabilities and market conditions. This understanding also enables leaders to anticipate potential challenges and to make proactive adjustments to their strategies.

Strategic Thinking Competencies

Strategic thinking requires a specific set of competencies that enable leaders to analyze complex situations, identify key issues, and develop effective strategies. Six critical strategic thinking competencies are:

1. Systems Thinking: The ability to see the organization as a whole and understand the interrelationships between its parts. This competency involves recognizing how changes in one area of the organization can impact others and how external factors influence the organization.

2. Creative Thinking: The ability to generate innovative ideas and solutions. Creative thinking is essential for developing strategies that differentiate the organization from its competitors and for responding to challenges in novel ways.

3. Critical Thinking: The ability to analyze information objectively and make reasoned judgments. Critical thinking helps leaders to identify the root causes of problems, evaluate potential solutions, and make informed decisions.

4. Visionary Thinking: The ability to imagine a future state for the organization and to develop strategies to achieve that vision. Visionary thinking involves setting long-term goals and identifying the steps needed to reach them.

5. Adaptive Thinking: The ability to adjust strategies in response to changing circumstances. Adaptive thinking is crucial in today’s volatile business environment, where organizations must be able to pivot quickly in response to new opportunities or threats.

6. Decision-Making: The ability to make timely and effective decisions. This competency involves weighing the risks and benefits of different options and choosing the course of action that best aligns with the organization’s goals.

These competencies are interrelated and often overlap. Effective strategic thinkers can integrate these competencies into their decision-making processes, enabling them to develop strategies that are both innovative and practical.

Tools and Models for Strategic Thinking

To enhance strategic thinking, various tools and models can be employed. These tools help leaders to structure their thinking, analyze complex situations, and develop effective strategies. Some of the key tools and models include:

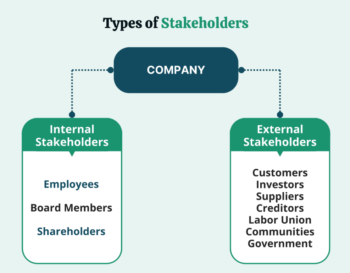

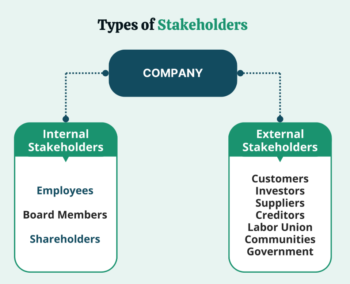

• Stakeholder Mapping: This tool helps leaders to identify and analyze the stakeholders who can impact or are impacted by the organization’s strategies. By understanding the needs, expectations, and influence of different stakeholders, leaders can develop strategies that align with stakeholder interests and foster collaboration.

• Design Thinking: A human-centered approach to innovation, design thinking involves understanding the needs of users, generating creative solutions, and testing and refining those solutions. This approach is particularly useful for developing strategies that are responsive to customer needs and that foster innovation.

• CYnefin Model: This framework helps leaders to understand the nature of the problems they face and to select the appropriate approach for solving them. The CYnefin model categorizes problems into four domains: simple, complicated, complex, and chaotic, each requiring a different approach.

• Contingency Theory of Leadership: This theory posits that there is no one best way to lead an organization; instead, the effectiveness of leadership depends on the context. Leaders must adapt their style and strategies to fit the specific circumstances they face.

• Dilts’ Neurological Levels: This model provides a framework for understanding the different levels of human experience and how they influence behavior. By understanding these levels, leaders can develop strategies that address the underlying motivations and needs of employees.

• Hudson’s Wheel of Change: This model helps leaders to navigate the change process by understanding the different stages of change and the challenges associated with each stage. By applying this model, leaders can develop strategies that support employees through the change process and that minimize resistance.

These tools and models provide a structured approach to strategic thinking, helping leaders to analyze complex situations, generate creative solutions, and develop effective strategies.

The Human Element in Strategic Thinking

One of the key insights of Human Strategic Thinking is the recognition that people are at the heart of every strategic initiative. While strategies may be designed at the top levels of an organization, their success depends on the engagement, commitment, and capabilities of the people who implement them.

The human element in strategic thinking involves understanding how people react to change, how they are motivated, and how they can be supported to contribute to the organization’s success. This includes fostering a culture of collaboration, communication, and continuous learning, as well as addressing the human factors that can hinder strategic success, such as resistance to change or lack of alignment with organizational goals.

By integrating the human element into strategic thinking, leaders can develop strategies that are not only effective but also sustainable. This approach ensures that the organization’s people are engaged, motivated, and aligned with the strategic goals, leading to better outcomes and greater value creation.

Case Study: IBM’s Strategic Transformation

In the early 1990s, IBM, once a giant in the technology industry, faced a dire situation. The company was struggling with declining market share, escalating costs, and intense competition in a rapidly evolving technology landscape. Its traditional focus on hardware, particularly mainframes, was becoming obsolete as personal computers and decentralized computing gained prominence. By 1993, IBM was on the brink of bankruptcy, having reported a record loss of $8 billion the previous year.

Amid this crisis, Louis V. Gerstner Jr. was appointed as IBM’s CEO. Unlike his predecessors, Gerstner was an outsider to the technology industry, bringing a fresh perspective focused on business outcomes rather than technology for its own sake. He quickly recognized that IBM’s reliance on hardware was unsustainable and that the company needed to shift its focus towards services and solutions.

Gerstner’s strategy involved repositioning IBM as a services-led company. He emphasized the need for integrated solutions that combined hardware, software, and services to address customers’ business needs. This shift was marked by significant investments in IBM Global Services, which soon became the company’s most successful division, offering IT consulting, systems integration, and outsourcing services.

To streamline operations and focus on this new direction, Gerstner also led the divestiture of non-core businesses, including the sale of IBM’s networking hardware business to Cisco and its personal computer division to Lenovo. These moves allowed IBM to free up resources and concentrate on growing its services and software sectors.

A critical element of this transformation was the focus on IBM’s internal culture. Gerstner recognized that the company’s bureaucratic and siloed structure was stifling innovation and hindering collaboration. To address this, he broke down organizational silos, promoted cross-functional teamwork, and introduced a performance-based culture that rewarded innovation and results. He also streamlined decision-making processes, giving employees more autonomy and reducing management layers that had slowed down the company’s responsiveness.

Gerstner’s leadership emphasized the alignment of culture with strategic goals. He communicated a clear vision centered on customer focus, operational excellence, and continuous improvement. These values were reinforced through leadership development programs and performance incentives, creating a culture where employees were motivated to contribute to the company’s transformation.

The results of IBM’s strategic shift were remarkable. By the end of the 1990s, IBM had returned to profitability, with its services division leading the industry. The company’s software business, particularly in middleware, became a major contributor to its success. IBM’s stock price rebounded, and the company regained its position as a market leader.

Gerstner’s leadership is credited with saving IBM and setting the stage for its continued success into the 21st century. The case of IBM’s transformation highlights several key lessons: the importance of strategic agility, the role of leadership in driving change, the need for a holistic approach to strategy, and the power of culture in enabling strategic success.

IBM’s journey demonstrates that successful transformation requires more than just strategic shifts—it requires a deep alignment between strategy, culture, and leadership to navigate challenges and seize new opportunities in a rapidly changing environment.

Case Study: Netflix’s Strategic Shift

Netflix, founded in 1997 as a DVD rental-by-mail service, faced a rapidly changing technological landscape in the early 2000s. The rise of digital technology, faster internet speeds, and shifting consumer behaviors signaled that the future of entertainment would be online. Recognizing these trends, Netflix, under the leadership of co-founder and CEO Reed Hastings, made a bold strategic decision to pivot from its original DVD rental business to become a streaming service and, eventually, a content creator.

The transition began in 2007 when Netflix launched its streaming service, allowing subscribers to instantly watch TV shows and movies online. This move was revolutionary at a time when streaming was still in its infancy. Hastings and his team understood that the convenience of on-demand content would appeal to a growing number of consumers who were increasingly looking to the internet for entertainment. However, this shift required not only technological innovation but also a fundamental change in Netflix’s business model and company culture.

Technologically, Netflix had to invest heavily in building a robust streaming platform capable of delivering high-quality content to millions of users simultaneously. This involved developing sophisticated algorithms to recommend content, creating partnerships with internet service providers to ensure smooth streaming, and continually updating its platform to improve user experience. The company’s technological prowess became a key differentiator in the crowded entertainment market.

However, the strategic shift to streaming posed significant challenges beyond technology. Netflix needed to renegotiate licensing deals with content providers, who were initially reluctant to embrace streaming, fearing it would cannibalize their traditional revenue streams. Over time, as streaming gained popularity, these providers began to see Netflix as a competitor rather than a partner, leading to the loss of some content licenses. This challenge underscored the need for Netflix to evolve from simply a distributor of content to a producer of original content.

In 2013, Netflix made its next major strategic leap by entering the world of content creation with the release of its first original series, House of Cards. This move marked the beginning of Netflix’s transformation into a full-fledged entertainment studio. By producing its own content, Netflix gained control over its library, reducing its reliance on external providers and allowing it to differentiate itself from competitors.

This shift required a significant cultural transformation within Netflix. Hastings and his leadership team recognized that to stay ahead in the rapidly evolving entertainment industry, the company needed a culture that encouraged risk-taking, innovation, and rapid decision-making. Netflix adopted a unique corporate culture centered around the principles of “freedom and responsibility.” Employees were given the autonomy to make decisions and were encouraged to take risks in pursuit of innovation. This culture was supported by a flat organizational structure, where hierarchy was minimized, and communication was open and transparent.

Netflix’s culture of freedom and responsibility extended to its approach to content creation. Creators were given significant creative control, which attracted top talent in the industry and resulted in the production of high-quality, original content. This approach also allowed Netflix to rapidly expand its content library and appeal to a global audience with diverse tastes.

The strategic shifts that Netflix undertook—moving from DVD rentals to streaming and then to original content creation—transformed the company from a niche service provider into a global entertainment powerhouse. By 2020, Netflix had over 200 million subscribers worldwide and had become one of the most influential players in the entertainment industry, with a vast library of content spanning genres, languages, and cultures.

The success of Netflix’s strategic shift offers several key lessons. First, it highlights the importance of staying ahead of technological trends and being willing to disrupt one’s own business model to adapt to changing market conditions. Second, it underscores the value of a strong, adaptive company culture that empowers employees to innovate and take ownership of their work. Finally, Netflix’s journey illustrates the power of content in the digital age—owning and producing content not only provides control and differentiation but also drives long-term growth and resilience in a competitive market.

Through its strategic foresight and cultural transformation, Netflix not only survived the shift from physical media to digital but emerged as a leader in the global entertainment industry, setting the standard for streaming services and original content production.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Changing Perspective

Perspective in this context is defined as encompassing two key elements. First, it involves who you are, where you are, your focus, and the tools you use—all of which influence what you see and how you interpret it. Second, it involves what you perceive in any given situation. The chapter explores how these factors combine to shape one’s overall perspective, which is essential in forming accurate judgments and strategies.

The chapter draws a clear distinction between perspective and perception. Perception is described as the filters and interpretations applied to sensory inputs—what we see, hear, or feel—that ultimately shape our perspective. For example, a 5-year-old and a 75-year-old may perceive a 40-year-old person very differently, even though the person remains unchanged. This example illustrates how perception, influenced by one’s point of view and experiences, can vary significantly and affect how reality is interpreted.

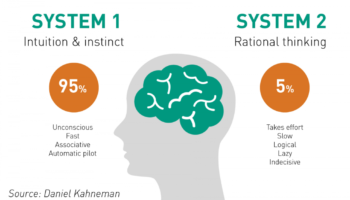

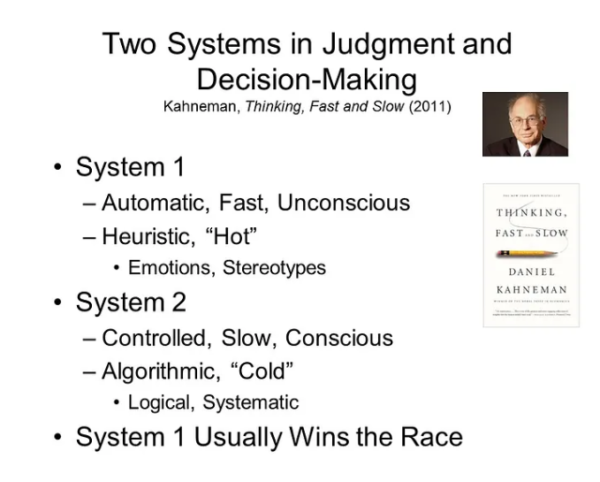

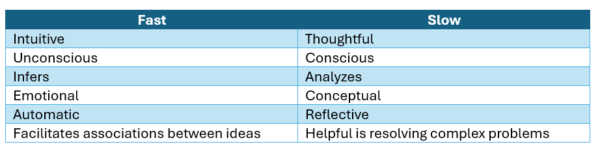

The chapter introduces Daniel Kahneman’s theory of dual thought systems: System 1 and System 2. System 1 is characterized as fast, intuitive, and automatic—ideal for routine tasks requiring little conscious effort. In contrast, System 2 is slow, analytical, and deliberate, used for complex problem-solving. While System 1 allows for quick decision-making, it is also prone to errors and biases due to its reliance on shortcuts and assumptions.

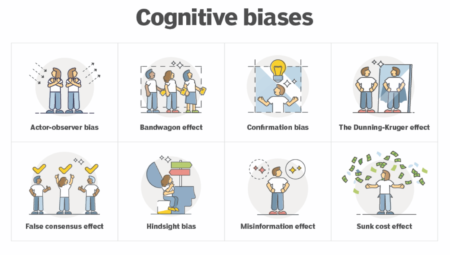

A key focus of this chapter is on cognitive biases, which are systematic errors in thinking that affect judgments and decisions. These biases arise from the mind’s tendency to favor efficiency, often relying on System 1 thinking. For instance, discrimination is a form of bias where more or less value is attributed to a person or idea based on how similar or different it is to the observer’s preexisting beliefs or preferences. The chapter highlights the need to recognize and mitigate these biases to improve the quality of strategic decisions.

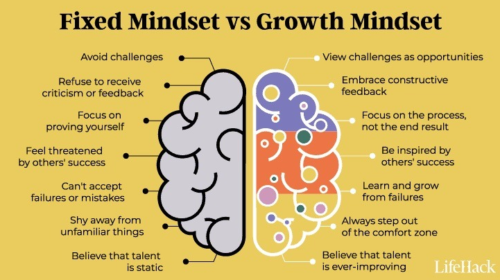

The chapter concludes by stressing the necessity of changing one’s perspective in strategic contexts. The ability to shift perspective is crucial for broadening one’s understanding and enhancing perception. Strategic thinking often requires taking a bird’s eye view—stepping back or even sideways—to fully grasp the complexities of a situation and to make well-informed decisions. By altering perspective, one can avoid the pitfalls of narrow or biased thinking and uncover insights that might otherwise be missed.

Changing Perspective sets the stage for understanding how deeply our perceptions and thought processes influence our strategic thinking. The chapter underscores the importance of being aware of and deliberately adjusting our perspectives to improve the accuracy of our decisions and the effectiveness of our strategies.

Chapter 2: The Evolution of Strategy

Chapter 2 traces the development of strategic thinking from its origins in military doctrine to its current application in the business world. This chapter provides a foundational understanding of how strategy has evolved over time and highlights the challenges and paradoxes that organizations face in crafting effective strategies today.

The concept of strategy originated in the military, where it was primarily focused on survival and defeating enemies. The term itself is derived from the Greek word strategos, meaning “generalship.” Military strategy involved meticulous planning, resource allocation, and tactical maneuvers designed to outwit and overpower adversaries. These principles, initially confined to the battlefield, have since been adapted and applied to business contexts, where the “enemies” are competitors, and the “battles” involve market share, innovation, and customer loyalty.

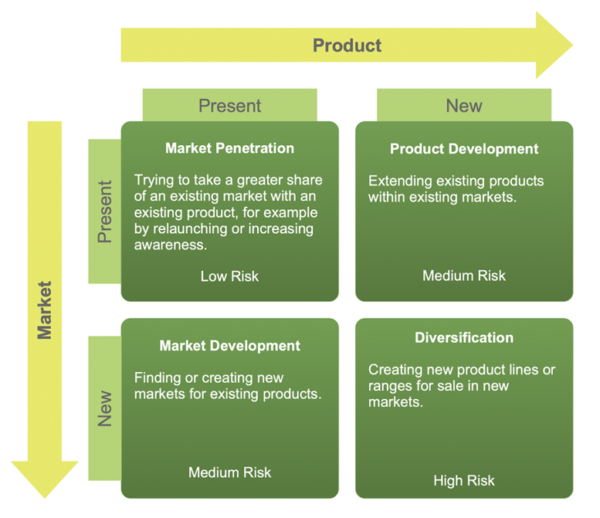

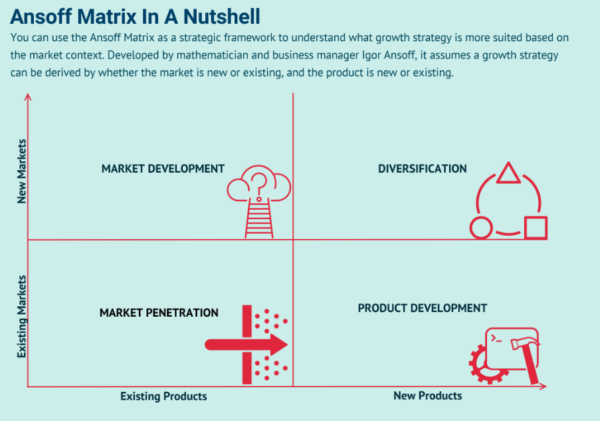

The business world was formally introduced to the concept of strategy through the work of H. Igor Ansoff, often referred to as the “father of strategic management.” Ansoff’s contributions brought strategic thinking to the forefront of business management, emphasizing the importance of a company’s ability to adapt to its environment in order to thrive. One of his most significant contributions was the development of Ansoff’s Matrix, a tool that helps organizations assess growth opportunities and manage risks through four strategic options: market penetration, market development, product development, and diversification.

As strategic thinking became more integrated into business practices, various efficiency approaches and tools were developed to aid in the formulation and execution of strategy. However, these efforts often yielded mixed results. Strategy became a specialized discipline within organizations, sometimes leading to its disconnection from day-to-day operations. While strategic analyses were thorough and plans were detailed, there was frequently a gap between the creation of a strategy and its successful implementation. This disconnect left many organizations struggling to translate strategic plans into actionable steps that could be understood and executed by all members of the organization.

Several key trends have shaped the evolution of business strategy over the decades. These include diversification, globalization, offshoring, reengineering, and the integration of new technologies. Diversification involved expanding into new markets or product lines to spread risk and capitalize on new opportunities. Globalization and offshoring allowed companies to tap into international markets and reduce costs by relocating production to countries with lower labor costs. Reengineering focused on redesigning business processes to improve efficiency and effectiveness. The rapid advancement of technology has also played a critical role, enabling new business models, disrupting traditional industries, and requiring companies to continuously adapt their strategies to remain competitive.

The chapter also explores several paradoxes inherent in strategic decision-making. For instance, the most accessible routes to potential customers are often the most crowded, limiting the ability of businesses to stand out. Conversely, paths that offer new opportunities often require innovation and a willingness to take risks, which can be more challenging. Additionally, while control is essential for managing risks, it can also stifle creativity and movement, creating new risks in the process. Therefore, a delicate balance between control and flexibility is necessary for effective strategic management.

Finally, the chapter emphasizes the need for clarity in goals and rules, paired with the adaptability to respond to changing circumstances and unforeseen opportunities. Successful strategy requires a clear understanding of objectives, but also the agility to pivot when necessary. This balance allows organizations to navigate the complexities of the business environment and maintain resilience in the face of change.

The Evolution of Strategy provides a historical overview of how strategic thinking has developed and highlights the ongoing challenges and paradoxes faced by organizations in crafting and executing effective strategies. This chapter sets the stage for deeper exploration of strategic tools and frameworks that will be covered in subsequent parts of the course.

Chapter 3: What is Strategic Thinking?

This chapter highlights the shift from traditional strategic planning to a more dynamic and inclusive approach that emphasizes adaptability, collaboration, and innovation.

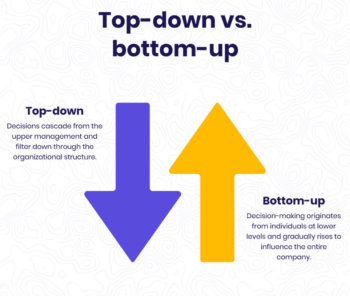

The concept of strategic thinking has undergone significant transformations, moving away from rigid planning exercises that focused solely on achieving predetermined outputs. Traditionally, strategy was a top-down process where plans were meticulously crafted by senior leaders and executed by the organization with little room for deviation. Adaptations to changing circumstances were often slow, as decision-making was centralized at the highest levels. This approach, while structured, was often ill-equipped to handle the volatility, uncertainty, and complexity of modern business environments.

As organizations faced increasing complexity and rapid change, the limitations of traditional strategic planning became apparent. Strategic thinking evolved to become a more flexible and inclusive process, enabling quicker and more effective responses to unforeseen challenges. This shift has allowed more decision-makers within an organization to contribute to its strategic agility, enhancing the organization’s resilience in the face of uncertainty.

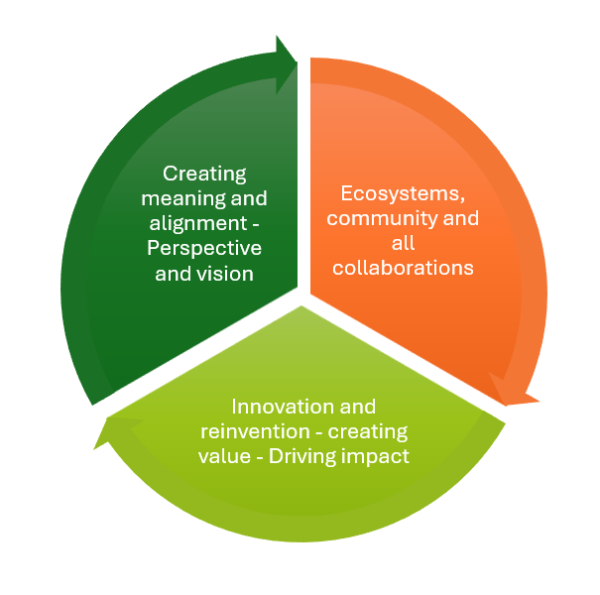

The chapter introduces a comprehensive model of strategic thinking, developed by B. Petitpas and A-L. Marcadet. This model consists of three interrelated components that together form a holistic approach to strategic thinking:

1. Creating Meaning and Alignment – Perspective and Vision: This component emphasizes the importance of gaining a broad, comprehensive view of the organizational landscape—what is often referred to as a bird’s-eye view. Strategic thinking in this context involves looking beyond immediate operational realities to understand broader trends, challenges, and opportunities. The goal is to define a clear vision for the organization’s future, create meaning for its stakeholders, and align strategic actions with this vision. By doing so, organizations can ensure that their strategies are not only well-conceived but also deeply connected to their long-term goals.

2. Innovation and Reinvention – Creating Value – Driving Impact: Strategic thinking is not just about planning; it’s about delivering results. This component focuses on the need for organizations to innovate, reinvent themselves, and create value in ways that have a tangible impact. In today’s competitive environment, organizations must be willing to see and act differently, embracing innovation as a core element of their strategy. This is where the theoretical aspects of strategy are put into practice—where ideas are tested, refined, and implemented to achieve real-world outcomes.

3. Ecosystems, Community, and Collaboration: The final component of the model underscores the importance of collaboration within and beyond the organization. Strategic thinking requires understanding and engaging with both internal and external ecosystems, including stakeholders, partners, and communities. Effective collaboration ensures that the organization’s strategy is not developed in isolation but is informed by and aligned with the needs and perspectives of all relevant parties. This collaborative approach is particularly crucial in today’s interconnected world, where the success of an organization often depends on its ability to work effectively with others.

For the purposes of this program, strategic thinking is defined as the ability to take a global, integrated view of the organization and its environment. It involves clarifying what is truly important for the future and sustainability of the organization and making decisions that align with this long-term vision. Strategic thinking requires integrating both known and unknown factors, balancing short-term actions with long-term goals, and considering the needs of the organization’s various ecosystems.

One of the key takeaways from this chapter is that strategic thinking should not be confined to senior leadership. Instead, everyone within the organization, regardless of their role or hierarchical level, should be encouraged to think and act strategically. This inclusive approach is particularly important in a teleworking context, where understanding the organization’s broader goals and the needs of others is essential for effective collaboration.

By adopting the strategic thinking model presented in this chapter, organizations can better navigate the complexities of today’s business environment and achieve sustained success.

Chapter 4 : What Do We Mean by Focusing on the Human Element?

Chapter 4 emphasizes the critical role that people play in the success or failure of strategic initiatives. While strategies often falter due to poor execution, a closer examination frequently reveals that the underlying cause is a lack of attention to the human element within the organization.

Organizations sometimes fail to achieve their strategic goals, and in some cases, they lose sight of those goals until they are required to report on progress. The human element is often the decisive factor in whether a strategy succeeds or fails. It is the people within an organization who are responsible for interpreting strategic goals, executing plans, and adapting to changes in the environment. If the human element is neglected—whether through poor communication, lack of alignment, or cultural misfit—the likelihood of strategic success diminishes significantly.

When individuals within an organization develop strong strategic thinking skills, they become better equipped to align their personal goals with the broader objectives of the organization. This alignment allows for more informed decision-making and the ability to adjust actions to better support the organization’s strategy. Strategic thinkers are also more capable of gaining a comprehensive understanding of their organization, its environment, and their team’s role within it. This broader perspective enables them to focus their efforts where they are most needed, track key metrics, and make decisions that are both effective and aligned with long-term goals.

The chapter presents several examples of how neglecting the human element can lead to strategic failure.

• Kodak: Once a dominant force in the photographic equipment industry, Kodak failed to adapt to the digital technology revolution. Despite being a pioneer in digital photography, Kodak was unable to transition its business model and culture to embrace this new technology. The company’s leadership underestimated the human resistance to change and the cultural attachment to traditional film. The result was a dramatic decline in market relevance, illustrating how failing to engage the human element in strategic shifts can have severe consequences.

• HP-Compaq Merger: The merger between HP and Compaq appeared to make sense on paper, offering potential synergies and market expansion. However, the merger ultimately struggled due to the stark cultural differences between the two companies. The “HP Way,” which emphasized a specific corporate culture and set of values, clashed with Compaq’s different approach. Poor communication and a lack of cultural integration led to internal conflicts and disrupted operations, demonstrating how misalignment of the human element can derail even the most promising strategic initiatives.

Conversely, the human element can be a powerful driver of innovation and success when it is effectively harnessed.

• Post-its: The invention of Post-it notes is a prime example of how a strategic mindset, combined with a focus on the human element, can turn a failure into success. Originally, the adhesive used in Post-its was considered a failure because it did not stick firmly. However, by shifting perspective and asking, “What can I do with this?”, the product was repurposed into one of the most successful office supplies in history. This success was driven by the ability to see potential where others saw failure—a hallmark of effective strategic thinking.

• Nintendo: Founded in 1889 as a playing card company, Nintendo’s evolution into a global leader in video games is another testament to the power of strategic thinking and innovation. The company’s success can be attributed to its willingness to experiment with different products and services over the years. This iterative approach, combined with a deep understanding of market trends and consumer preferences, enabled Nintendo to pivot from traditional entertainment to electronic gaming. The company’s leadership, particularly the founder’s grandson, exemplified how embracing the human element—through creativity, risk-taking, and adaptability—can lead to long-term success.

By focusing on the people who implement and are affected by strategic decisions, organizations can enhance their chances of success. Whether it’s avoiding the pitfalls that befell companies like Kodak and HP or emulating the innovative successes of companies like 3M and Nintendo, the human element is key to realizing the full potential of any strategic initiative.

This chapter highlights the critical role that human factors play in both the failures and successes of strategic initiatives, emphasizing the need for organizations to cultivate strategic thinking at all levels to fully leverage the human element.

Chapter 5: About Strategic Plans

Chapter 5 delves into the essential aspects of strategic planning within organizations. It outlines the purpose, processes, and content of strategic plans, emphasizing their critical role in guiding organizational efforts toward achieving defined goals.

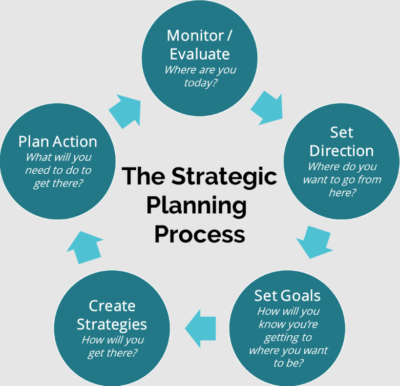

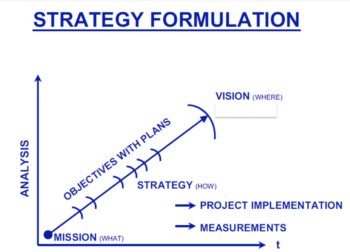

A strategic plan serves as a blueprint for an organization’s future, outlining the desired outcomes of its strategic efforts—often referred to as a “campaign.” Typically, a strategy includes three to seven key focus areas or “axes” that direct the organization’s actions. The timeline for strategic plans has evolved significantly over time. While long-term plans once spanned ten years, the rapid pace of change in today’s business environment has shortened the planning horizon to around 18-24 months. This shift reflects the need for organizations to remain agile and responsive to dynamic market conditions.

Strategic plans serve multiple purposes. Primarily, they provide a clear roadmap for what needs to be done, when, by whom, and how progress will be measured. This ensures that everyone in the organization is aligned and working towards the same objectives. Additionally, strategic plans function as vital communication tools, articulating the organization’s goals and strategies to all stakeholders, including employees, investors, and partners.

The process of developing a strategic plan varies depending on the organization’s structure and culture. In many cases, the Board of Administrators, or the owner in smaller organizations, is responsible for approving the strategic plan. However, the methods used to create the plan can differ significantly:

1. Top-Down Approach: In this approach, top leaders within the organization, typically executives, are responsible for developing the strategic plan. They then submit the plan to the Board for approval. The underlying assumption is that these leaders possess the necessary knowledge about the organization, its environment, market trends, capabilities, and potential threats to produce an accurate and effective strategic plan.

2. Top-Down with Specialist Input: This variation of the top-down approach involves top leaders taking the lead in creating the strategic plan, but inviting specialists or experts as needed to contribute to specific areas. This ensures that the plan is informed by specialized knowledge, which can enhance its accuracy and effectiveness.

3. Inclusive Approach: In an inclusive approach, a broader range of employees and stakeholders are involved in the strategic planning process. This method is more common in the non-profit sector, where collaboration and consensus-building are often prioritized. However, its use in for-profit organizations depends on the organizational culture and the leadership’s commitment to inclusivity. The inclusive approach allows for a diversity of perspectives, which can lead to a more comprehensive and robust strategic plan.

The content of a strategic plan typically covers several key areas, each of which is crucial to the organization’s success. These areas include:

• Market and Customers: Understanding the market and customer needs is fundamental to any strategic plan. This section outlines the organization’s target markets, customer segments, and strategies for meeting their needs.

• External Constraints: This includes an analysis of external factors that could impact the organization, such as regulatory requirements, economic conditions, and technological trends.

• Stakeholders: Strategic plans must consider the interests and needs of various stakeholders, including employees, investors, suppliers, and the broader community.

• Organizational Priorities: This section identifies the organization’s primary areas of focus, detailing specific objectives, success indicators, and deadlines for each priority.

• Functional Support: Finally, each function within the organization (such as marketing, finance, operations, etc.) specifies how it will contribute to achieving the overall strategic objectives. This ensures that all parts of the organization are aligned and working towards common goals.

Chapter 5 emphasizes the importance of strategic planning as a tool for organizational success. By clearly defining objectives, involving the right stakeholders, and regularly reviewing progress, organizations can navigate complex environments and achieve their strategic goals. The chapter also highlights the flexibility in approaches to strategic planning, allowing organizations to tailor the process to fit their unique culture and needs.

Chapter 6: Who is My Organization?

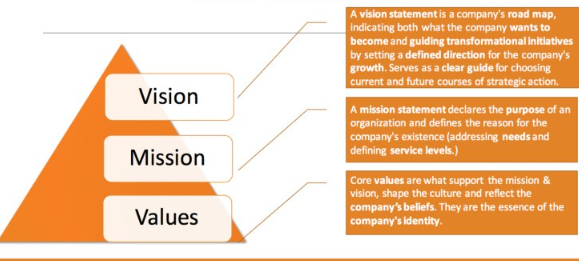

Chapter 6 explores the foundational concepts of an organization’s mission, vision, and values, emphasizing their critical roles in defining the identity, purpose, and aspirations of the organization. The chapter underscores the importance of these guiding statements in shaping decision-making, actions, and overall strategic direction.

The mission of an organization is its raison d’être—its reason for existence. It articulates the core purpose for which the organization was created and what it seeks to contribute to the world. More than just a statement of intent, the mission serves as a compass, guiding every decision, strategy, and action taken within the organization. It communicates to employees, customers, partners, and other stakeholders what the organization is about, what it provides, and why it matters.

A well-defined mission statement encapsulates the essence of the organization, touching upon what it offers and the value it aims to deliver. It also reflects the organization’s fundamental values, providing a sense of identity and continuity that helps align the efforts of all stakeholders towards a common goal. Whether the mission is to innovate in technology, provide affordable products, or deliver exceptional services, it serves as the foundation upon which the organization builds its strategies and measures its success.

In addition to the mission, a vision statement is equally critical in strategic planning. While the mission defines the organization’s current purpose, the vision describes what the organization aspires to become and achieve in the future. The vision is forward-looking, outlining the desired changes and advancements the organization seeks to accomplish over the next strategic plan. It serves as an inspirational guide, motivating employees and stakeholders by painting a picture of the organization’s future potential.

Sometimes, mission and vision statements are combined into a single, overarching declaration that captures both the organization’s current purpose and its future aspirations. Whether separate or combined, the vision statement provides a clear direction for the organization, helping to align long-term goals with day-to-day operations.

Values are at the heart of organizational culture. They are the lived beliefs and convictions that define how decisions are made, how people work and collaborate, and what is considered acceptable behavior. Values shape “how things are done here” and provide a framework for ensuring consistency in actions and decisions across the organization.

For values to be effective, they must support both the mission and vision. When these three pillars—mission, vision, and values—are aligned, they reinforce each other, creating a cohesive and strong organizational identity. This alignment helps to cultivate a culture of trust, engagement, and commitment among employees and stakeholders. However, when values are misaligned with the mission and vision, or when they are seen as mere lip service rather than truly lived principles, they can lead to cynicism and disengagement. This disconnect can be damaging to the organization’s morale and overall success.

The chapter provides examples of mission and vision statements from well-known organizations to illustrate how these statements define and differentiate a company:

• IKEA (Mission): “To offer a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.” This mission reflects IKEA’s commitment to making quality home furnishings accessible to a broad audience, emphasizing affordability, functionality, and design.

• Google (Mission): “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” This mission highlights Google’s goal of making information easily accessible to everyone, underscoring its role as a global leader in search technology.

• Tesla (Vision): “To create the most compelling car company of the 21st century by driving the world’s transition to electric vehicles.” Tesla’s vision statement reflects its ambition to lead the automotive industry’s shift toward sustainable energy, positioning itself as a trailblazer in electric vehicles.

• Amazon (Vision): “To be Earth’s most customer-centric company; to build a place where people can come to find and discover anything they might want to buy online.” Amazon’s vision emphasizes its goal of becoming the ultimate online destination for consumers, driven by a relentless focus on customer satisfaction.

These examples demonstrate how mission, vision, and values work together to encapsulate an organization’s purpose, aspirations, and principles, setting the tone for its strategic direction. Each statement provides a clear and concise description of what the organization seeks to achieve, guiding its actions and informing its stakeholders.

One of the key themes of this chapter is the alignment of organizational decisions and actions with the mission, vision, and values. For an organization to be successful, all its endeavors—from daily operations to long-term strategic initiatives—must be in harmony with these guiding pillars. This alignment ensures that the organization remains focused on its core purpose and future aspirations, avoids mission drift, and continues to deliver on its promises to stakeholders.

When the mission, vision, and values are clearly communicated and deeply ingrained in the organizational culture, they become powerful tools for decision-making. Employees at all levels can refer to these guiding statements when making choices, ensuring that their actions support both the current and future goals of the organization. This consistency helps build trust with stakeholders, as they can see that the organization is true to its values and committed to its purpose and vision.

Chapter 6 emphasizes that understanding and articulating the organization’s mission, vision, and values are crucial for defining its identity and guiding its strategic direction. These guiding statements are not just declarations of intent; they are the cornerstones of the organization’s strategy, shaping its decisions and actions at every level. By ensuring that all activities are aligned with the mission, vision, and values, organizations can maintain focus, build trust with stakeholders, and achieve sustained success.

Chapter 7: My Organization’s Industry

Chapter 7 provides an in-depth exploration of what constitutes an industry, the importance of understanding one’s industry, and the tools available for analyzing industry dynamics. The chapter highlights the significance of industries in shaping the strategic context within which organizations operate and how this understanding can be leveraged for competitive advantage.

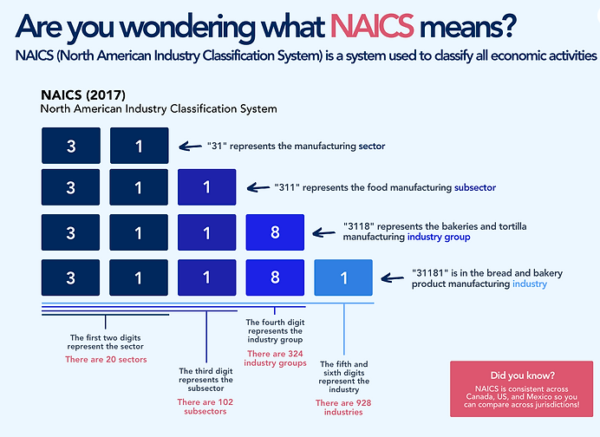

An industry is defined as a group of businesses that are similar in terms of their activities, products, or services. These businesses typically operate under the same regulatory and governmental frameworks, face similar market conditions, and share certain behavioral and value-based commonalities. The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) is one such system used to categorize and define industries, providing a standardized method for analyzing and comparing businesses within specific sectors.

The chapter provides examples of sectors and the industries that fall within them to illustrate the breadth and diversity of industry classifications:

• Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services Sector: This sector includes industries such as legal services, engineering services, management consulting services, computer systems design and related services, and advertising agencies. Each of these industries shares a focus on providing specialized professional services that require technical expertise and knowledge.

• Manufacturing Sector: This sector encompasses industries like industrial machinery manufacturing, semiconductor and electronic component manufacturing, navigational and medical instrument manufacturing, and dairy product manufacturing. These industries are involved in the production and manufacturing of goods, each with its own specific processes and technologies.

Understanding the specific industry in which an organization operates is crucial, as it determines the competitive landscape, regulatory environment, and the types of opportunities and challenges the organization is likely to face.

Industries are shaped by their participants, who typically receive similar treatment from government and regulatory agencies, benefit from the same types of support, and are subject to similar constraints. This shared environment fosters commonalities in behavior, values, and strategic challenges within industries. For example, businesses within the same industry often face similar competitive pressures, regulatory requirements, and market opportunities.

An industry’s characteristics also influence how companies within it interact with customers, suppliers, and competitors. This understanding is essential for developing effective strategies that align with industry norms and leverage the unique aspects of the industry to gain a competitive advantage.

The chapter distinguishes between the concepts of market and industry. While an industry encompasses a group of similar businesses, a market refers to the specific arena where transactions occur between a company and its customers. Markets exist within industries and can be segmented further into sub-markets based on different products, services, or customer demographics.

For example, within the travel industry, distinct markets may include tour operators, accommodations, and food and beverage services. Understanding the specific markets within an industry allows organizations to tailor their strategies to meet the needs of their target customers more effectively.

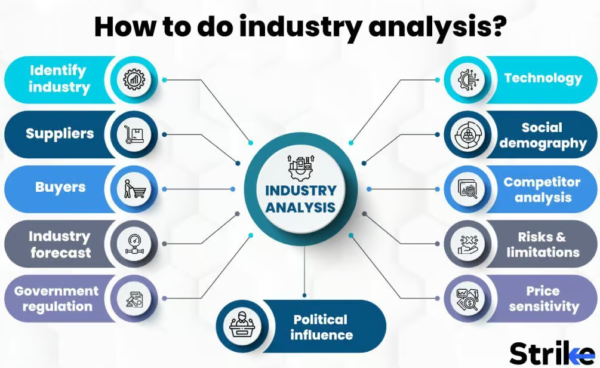

One of the key tools introduced in this chapter for analyzing industry dynamics is Porter’s Five Forces model. This framework helps organizations assess the competitive forces within their industry, which can influence profitability and strategic decision-making. The five forces are:

1. Competitive Rivalry: The intensity of competition among existing players in the industry. Lower differentiation between products typically leads to higher rivalry.