High-Performance Innovation – Workshop 1 (Scope Definition)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for High-Performance Innovation is provided by Mr. Auriach Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 48 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Mr. Auriach has experience in strategy, process & innovation performance, and digital marketing. He holds an engineering degree in aerospace from Sup’aero University (in Toulouse, France) and a master’s degree in Business Consulting from ESCP Business School (Paris, France). Mr. Auriach has industry experience in financial services, life sciences, aerospace, digital services, law, and education. He held various management positions in western Europe, including a Partner position at Accenture from 2005 to 2013. Mr. Auriach co-authored “Pro en consulting” at Vuibert editions, in collaboration with a strategy professor from ESCP.

Mr. Auriach’s personal achievements include: creating and developing new businesses up to $100 M in revenue; leveraging undervalued assets to transform businesses; aligning collaborative digital marketing processes and strategy; improving process performance; managing innovation portfolio ; carrying out post-merger integration ; orchestrating service line-wide strategy sharing ; Optimizing management reporting processes in global organizations.

Mr. Auriach’s service skills include: strategy; blue ocean strategy; process performance; lean ; training and training engineering ; digital marketing ; business consulting : innovation management. Mr. Auriach has more than 20 years of experience in business training, at Sup’aéro / ISAE aerospace engineering university in the late 90s, ESCP Business school since 2004, as an independent provider since 2013, at Celsa Sorbonne university from 2022.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

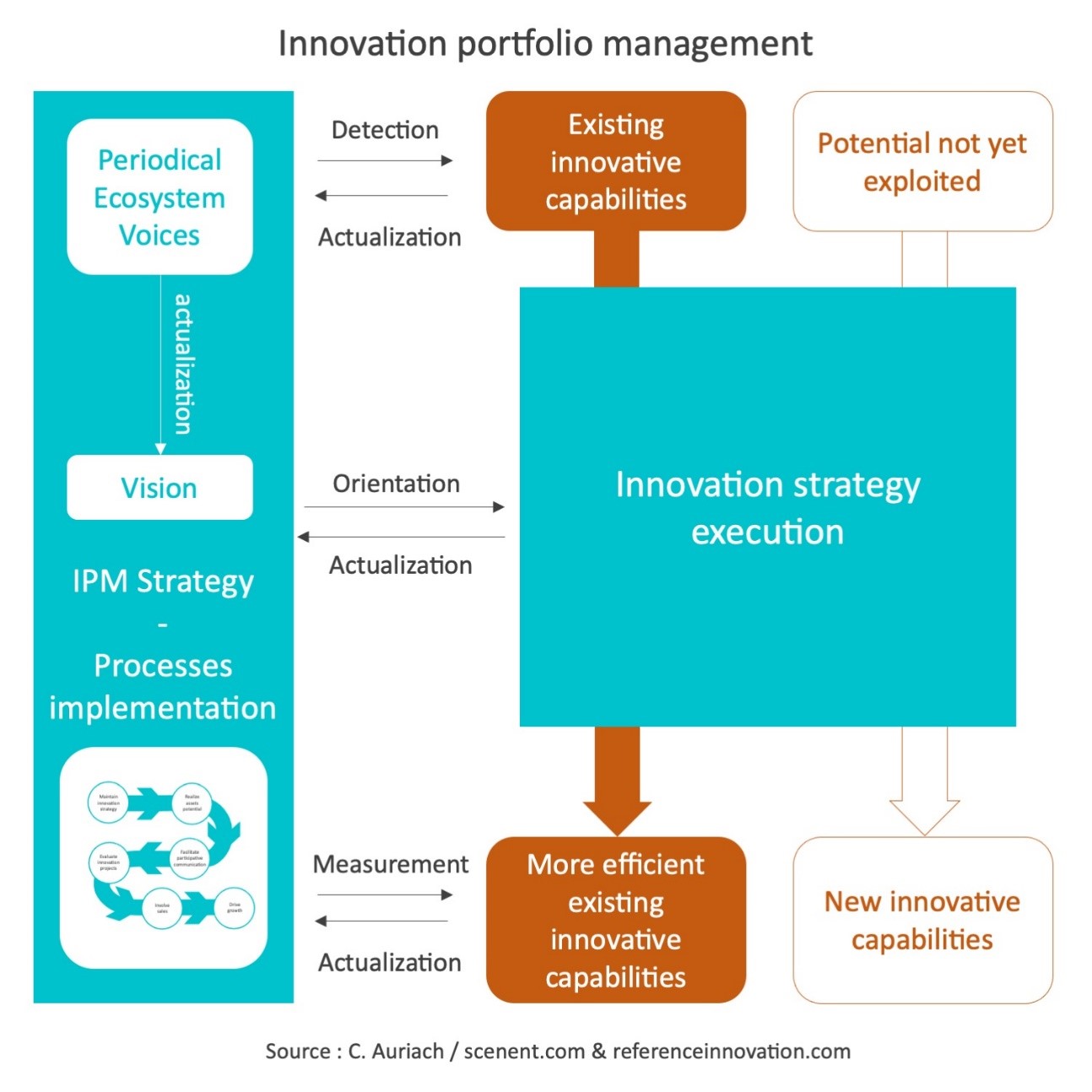

The first workshop of the High-Performance Innovation program leads to the formalization of a vision, a strategy and a questioning intended for potential contributors to the deployment of the IPM process, IPM meaning “Innovation Portfolio Management” or “Innovation Performance Management”. On this basis, a mapping of the maturities of the IPM process by organizational subset is built, hence the title of the workshop: scope definition.

Participants are exposed to the fundamentals of IPM during the workshop, in terms of strategy, process, organization and information systems, and are able to contextualize them according to their position in the field. They practice implementing them and produce a personalized framework for the IPM approach as a group. Collaborative tools that can be used in an IPM context are described and compared in order to lead participants to preselect the one that seems to them to be the most in tune with the culture of their organization. The adoption of a cellular, learning and agile organization is recommended and explained in order to begin a first phase of mobilization of part-time stakeholders. A portfolio of pilot projects is identified on the basis of the knowledge available to the participants, and will be completed between the first and the second workshop, thanks to the recommendation of a questioning method mentioned above. The content of this questioning is built by the participants via dedicated exercises. The performance indicators forming the basis of future monitoring dashboards are presented and projected onto the reality of the context of the organization concerned. The organization itself is broken down into coherent subsets from the point of view of the culture of innovation, and qualified in terms of the maturity of the initial IPM process. The IPM strategy is defined thanks to this maturity diagnosis, subset by subset, targeting the immediately higher level of maturity. A scale on 12 levels is used to concretize the formalization of the diagnosis as of the strategy. These elements will be supported by an initial communication plan favoring a participatory mode. The structure of a co-creation workshop that the participants can later facilitate themselves is provided, explained and tested during the session. The resulting content forms the basis of a heritage of stories and legends capable of creating or maintaining a culture of innovation. This dynamic can go beyond the sole framework of the organization via open innovation initiatives, the state of the art of which is described and the concepts tested in session. Participants are made aware of the importance of aligning innovative initiatives with the expectations of the ecosystem or the market, thanks in particular to the use of a method for qualifying a professional network.

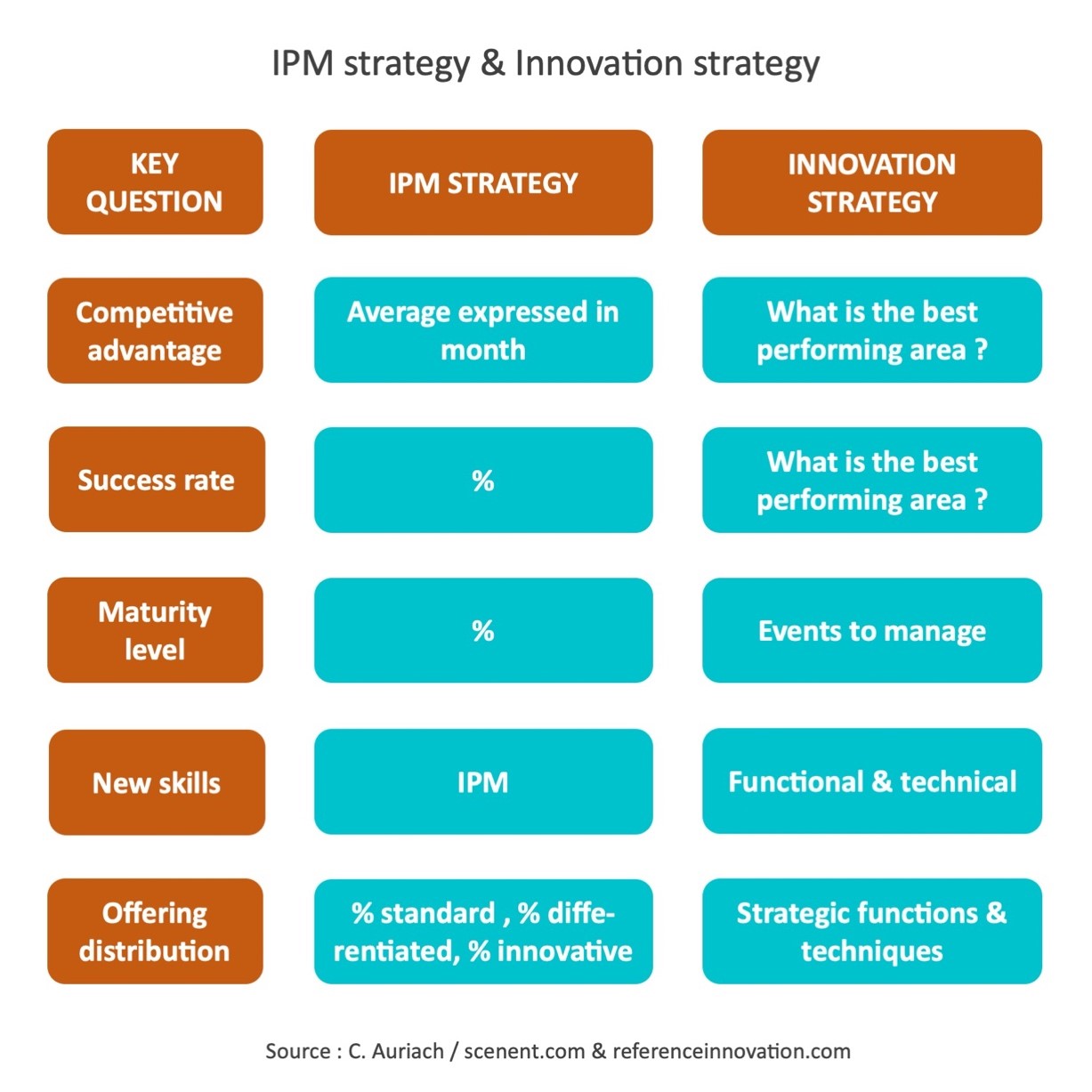

At the end of the workshop, the key result is the mapping of the organizational subsets, their diagnosis of IPM Process maturity and the IPM strategy which is deduced therefrom. Thanks to the 12 fundamental skills acquired by the participants, these elements will be maintained over time, supplemented and amended before the second workshop, during which the innovation strategy will be qualified, if it exists, or established, if it doesn’t. IPM strategy and innovation strategy are two different things: the first is dictated by the level of maturity of the IPM process and consists of aiming for the next level; the second is dictated by the expectations of the market or the ecosystem and by the analysis of the organization’s offerings, products or services.

Objectives

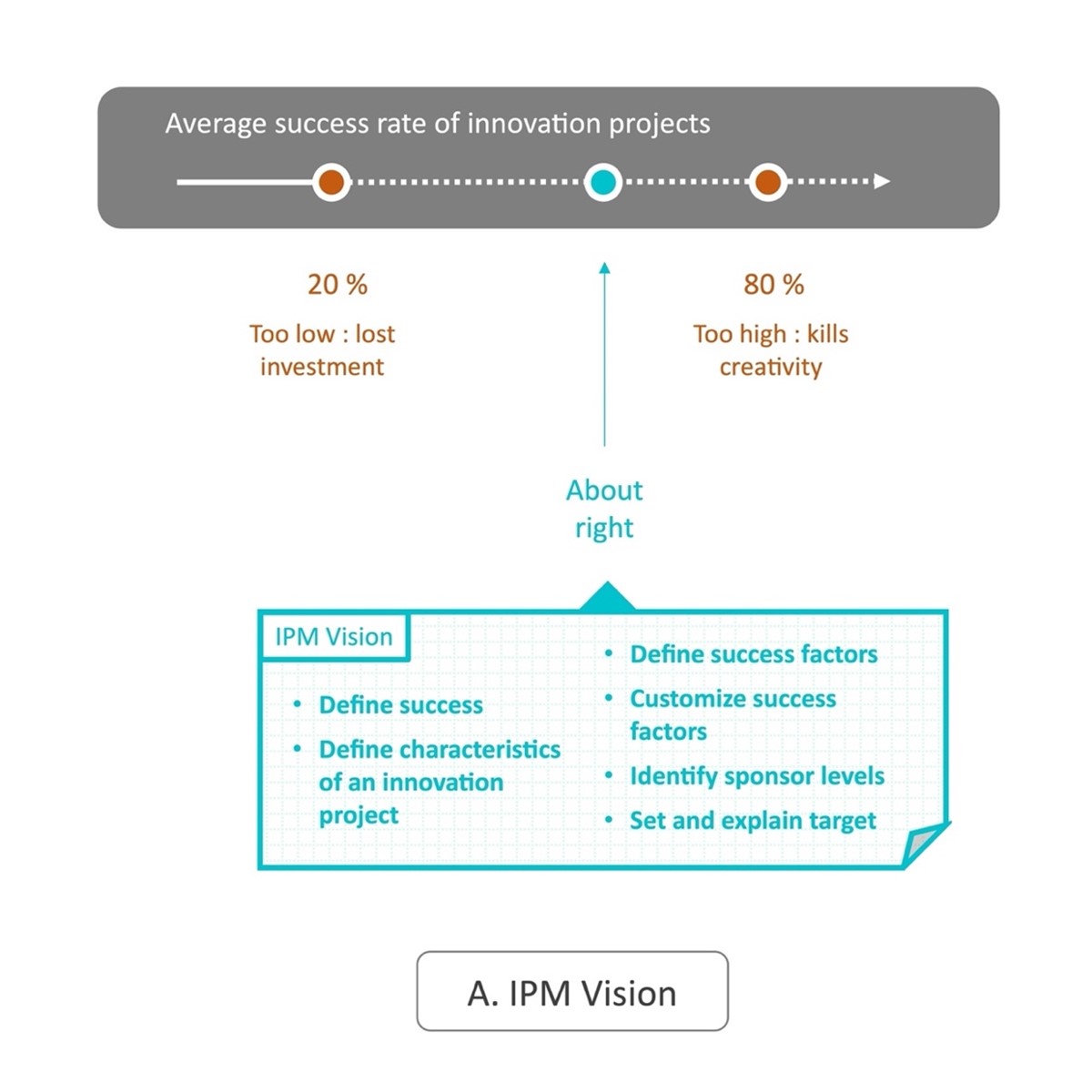

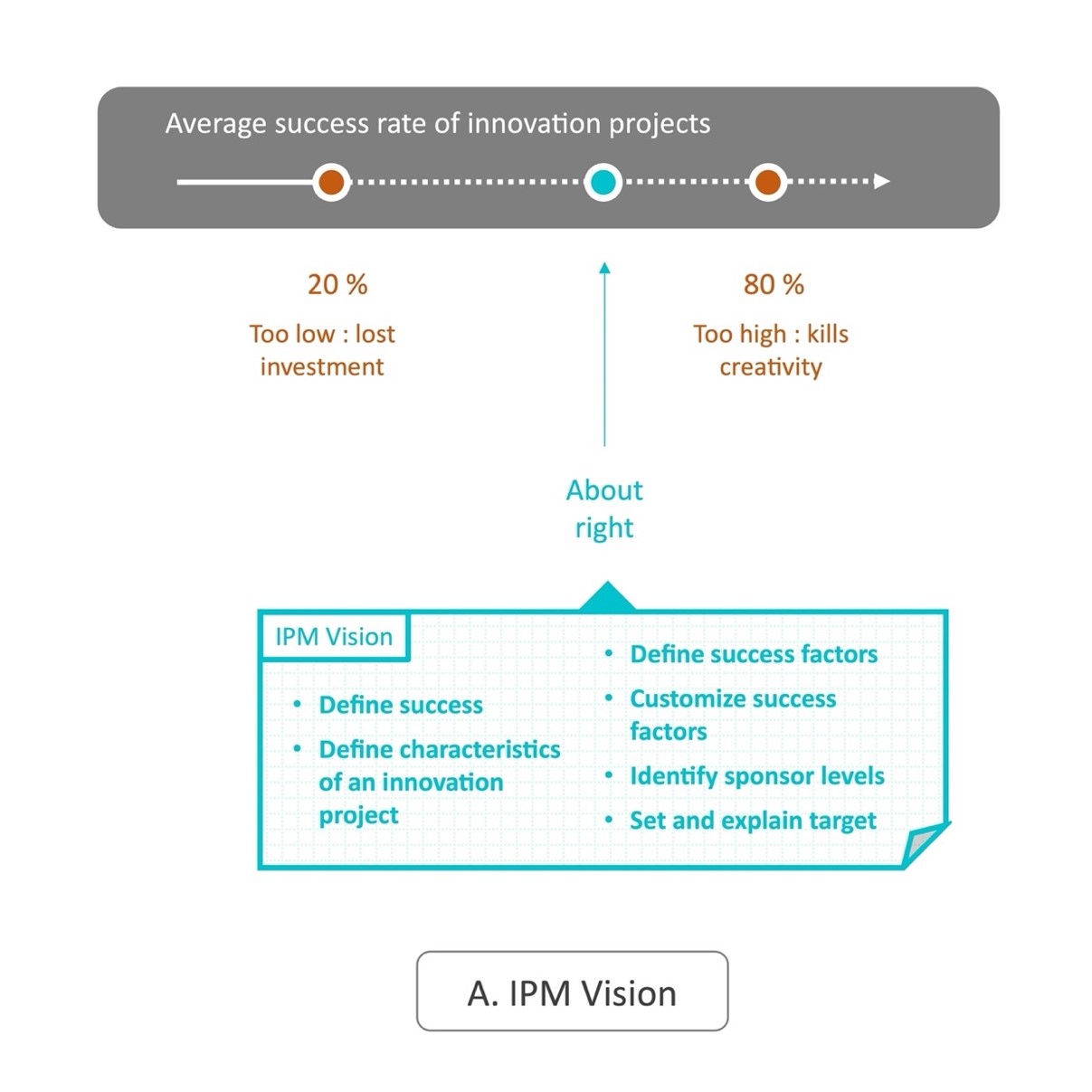

01. IPM vision: what success rate to aim for, at what pace, based on what assumptions?

02. Scope of application: breakdown of the organization into coherent subsets from the point of view of the culture of innovation.

03. Mapping of maturities: evaluation of the IPM process on each subset using a 12-level scale.

04. Cellular organization: description of the fundamentals of cellular, learning and agile organizations, and their 5 meta-rules. Application to the context of each subset to identify potential contributors to the IPM approach.

05. Collaborative tool: description of a range of generic and specialized tools adapted to an IPM context. Pre-selection of a generic tool within the organization, to be confirmed between the first and the second workshop.

06. Network of pioneers: definition of the primary roles of potential contributors to the IPM approach.

07. Pilot portfolio: construction of an initial portfolio of innovative pilot initiatives. An initiative is either an idea generating potential projects, or a framed and piloted innovation project. This framing and this management respect at all times a key principle: to stimulate the creativity of the stakeholders.

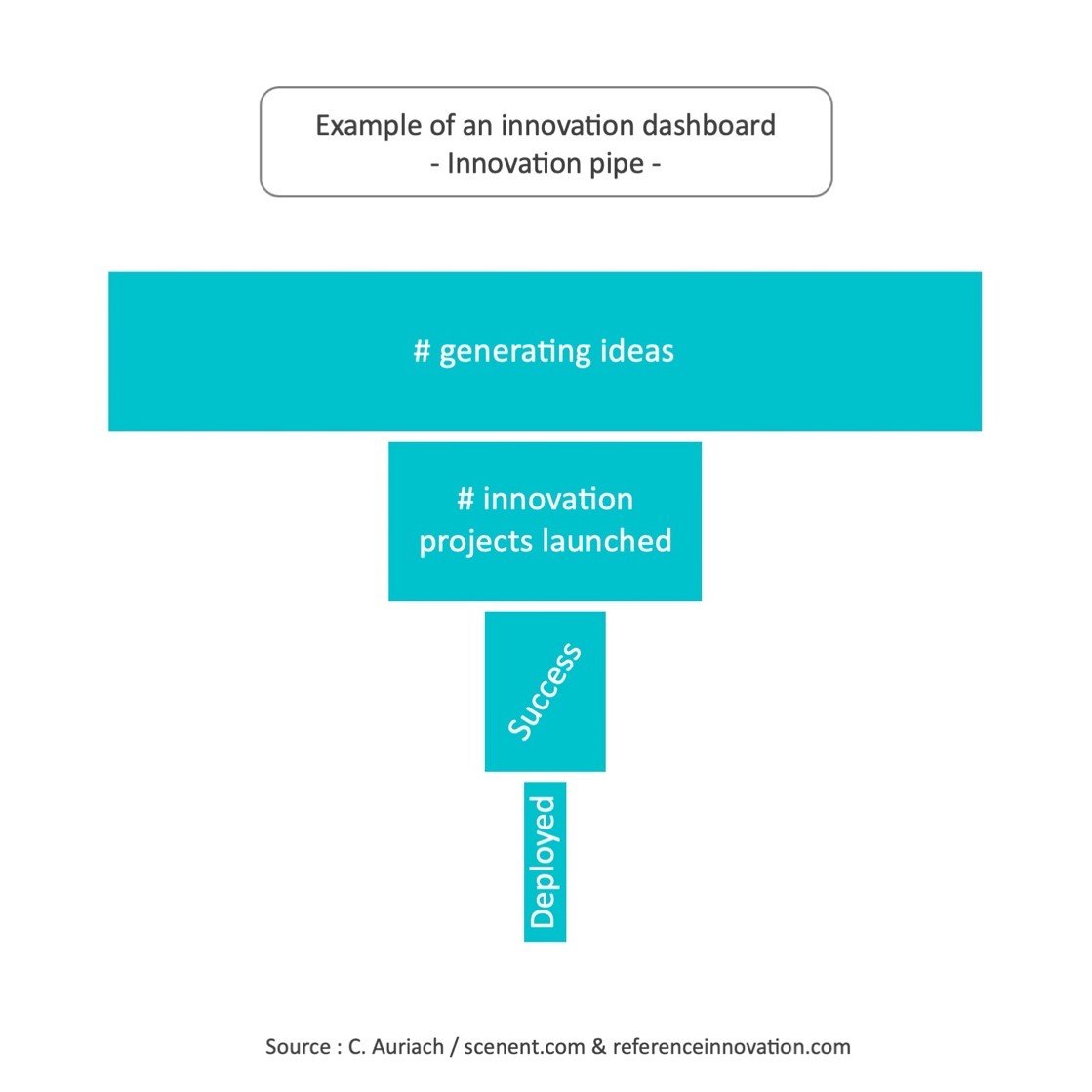

08. Initial dashboard: identification of the first indicators applicable to the context of the organization.

09. IPM strategy: based on the maturity diagnosis by subset, determination of the IPM strategy consisting of aiming for the higher level.

10. Storytelling: identification of stories of past or future innovation projects, capable of creating or maintaining a culture of innovation. Learning methods for conducting co-creativity workshops.

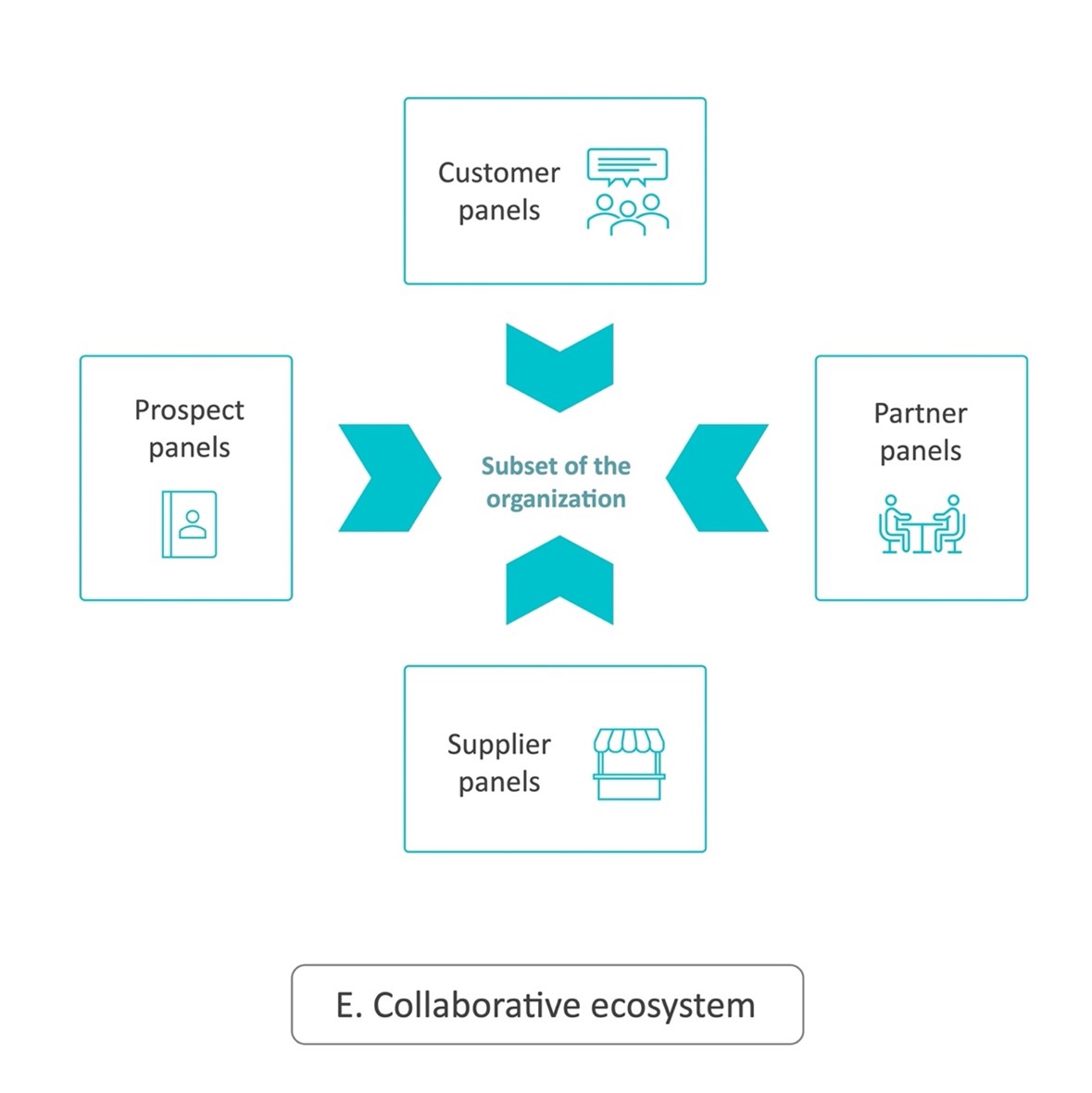

11. Collaborative ecosystem: application of the principles of open innovation to the context of the organization.

12. Initial communication plan: identification of the reasons for communicating on the subject of innovation, as well as targets, issuers, channels, situations, content and means.

Strategies

01. IPM vision

a) Identify and assign key roles

b) Share a frame of reference for innovation initiatives

c) Give rhythm

02. Scope of application

a) Map the organization at the macro level

b) Qualify the innovation culture of each subset

c) Revisit the cartography at macro level

03. Mapping of maturities

a) Compare the as-is situation to known innovative business models

b) Establish a diagnosis

c) Specify the diagnosis

04. Cellular organization

a) Understand the situations conducive to the implementation of a cellular organization

b) Adapt the principles of cellular organizations to the context

c) Preparing for the experiment

05. Collaborative tool

a) Choose a collaborative solution

b) Customize the solution

c) Specify the key use cases

06. Network of Pioneers

a) Identify contributors potential

b) Anticipate collection of information

c) Mobilize contributors

07. Pilot portfolio

a) Visualize a portfolio target

b) Initialize a pilot portfolio

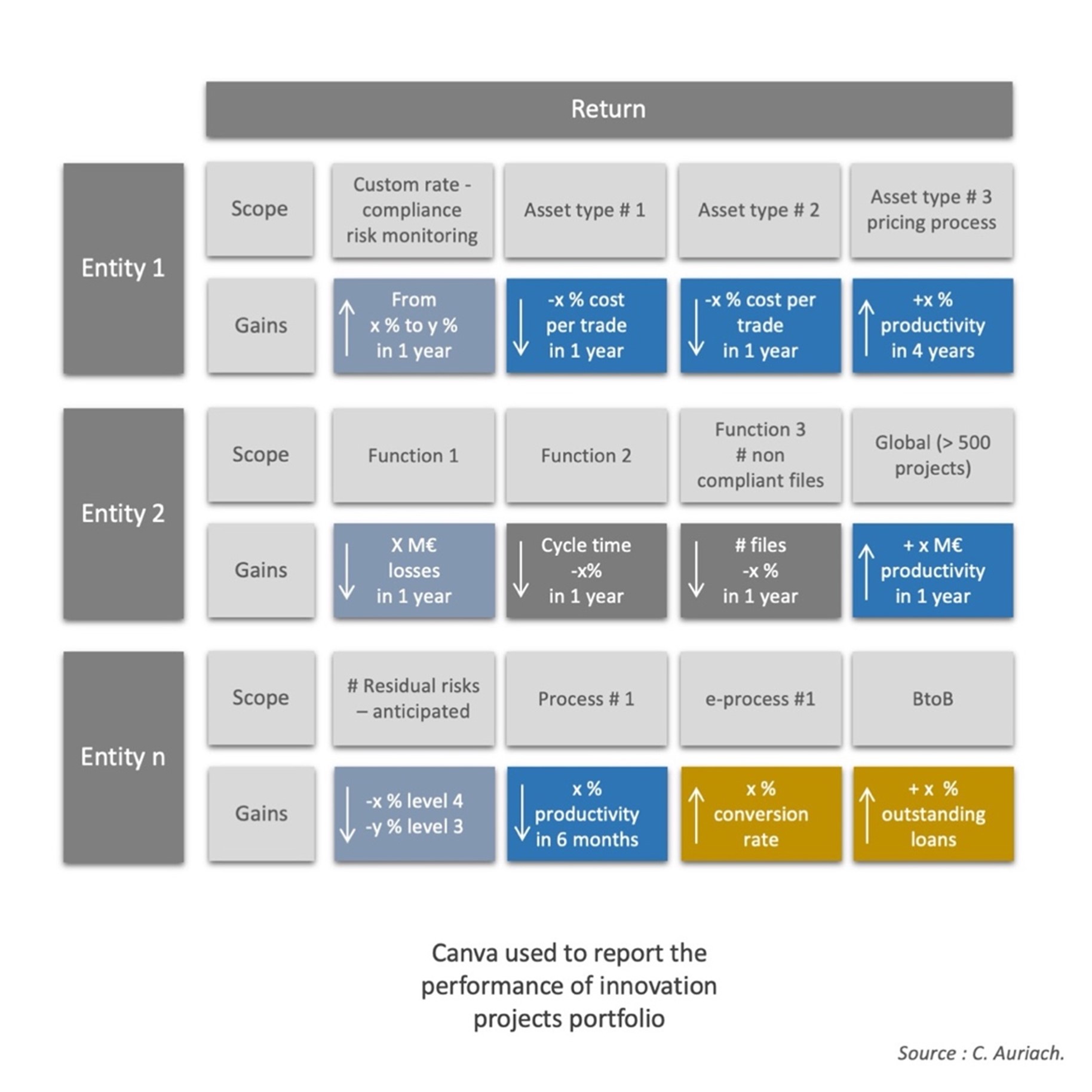

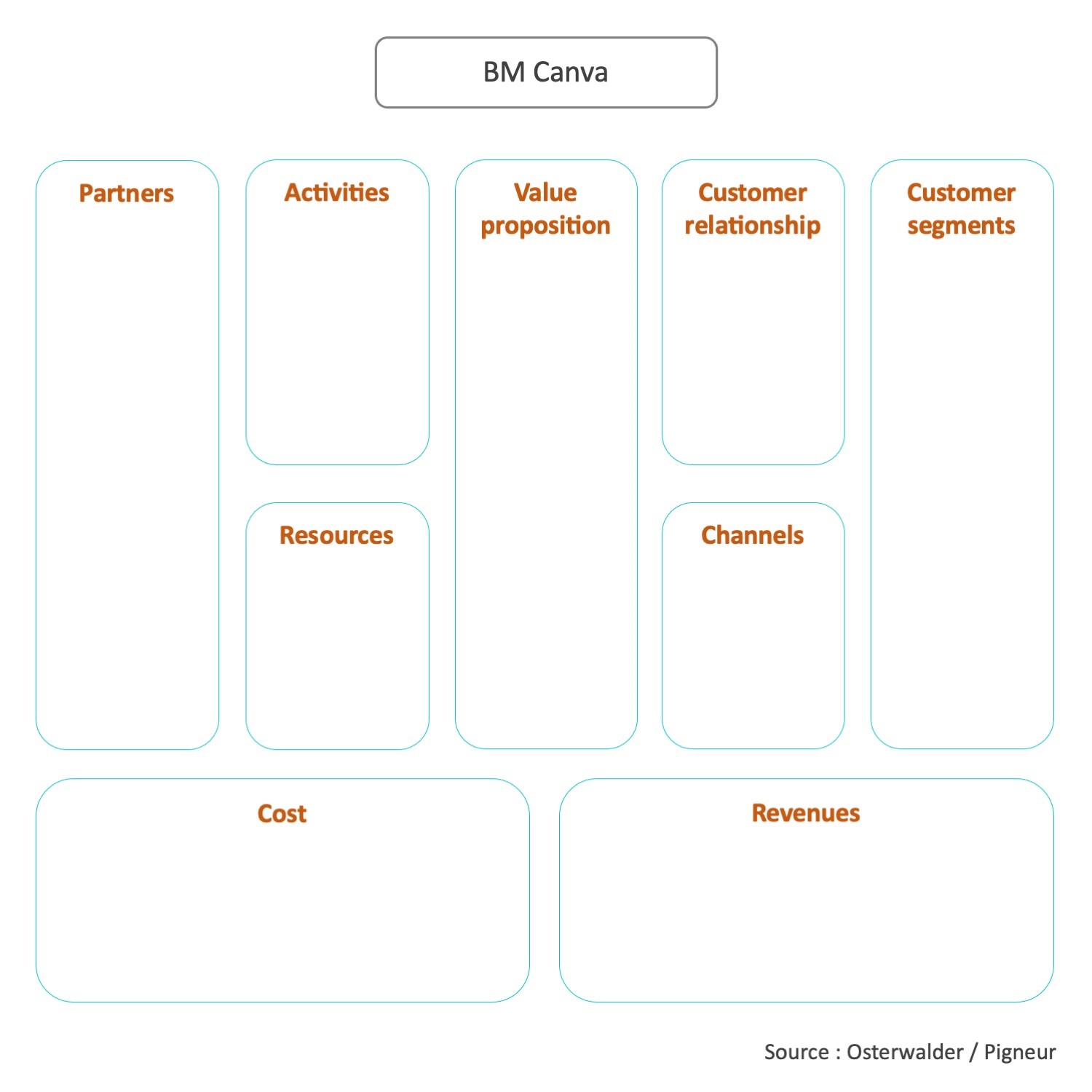

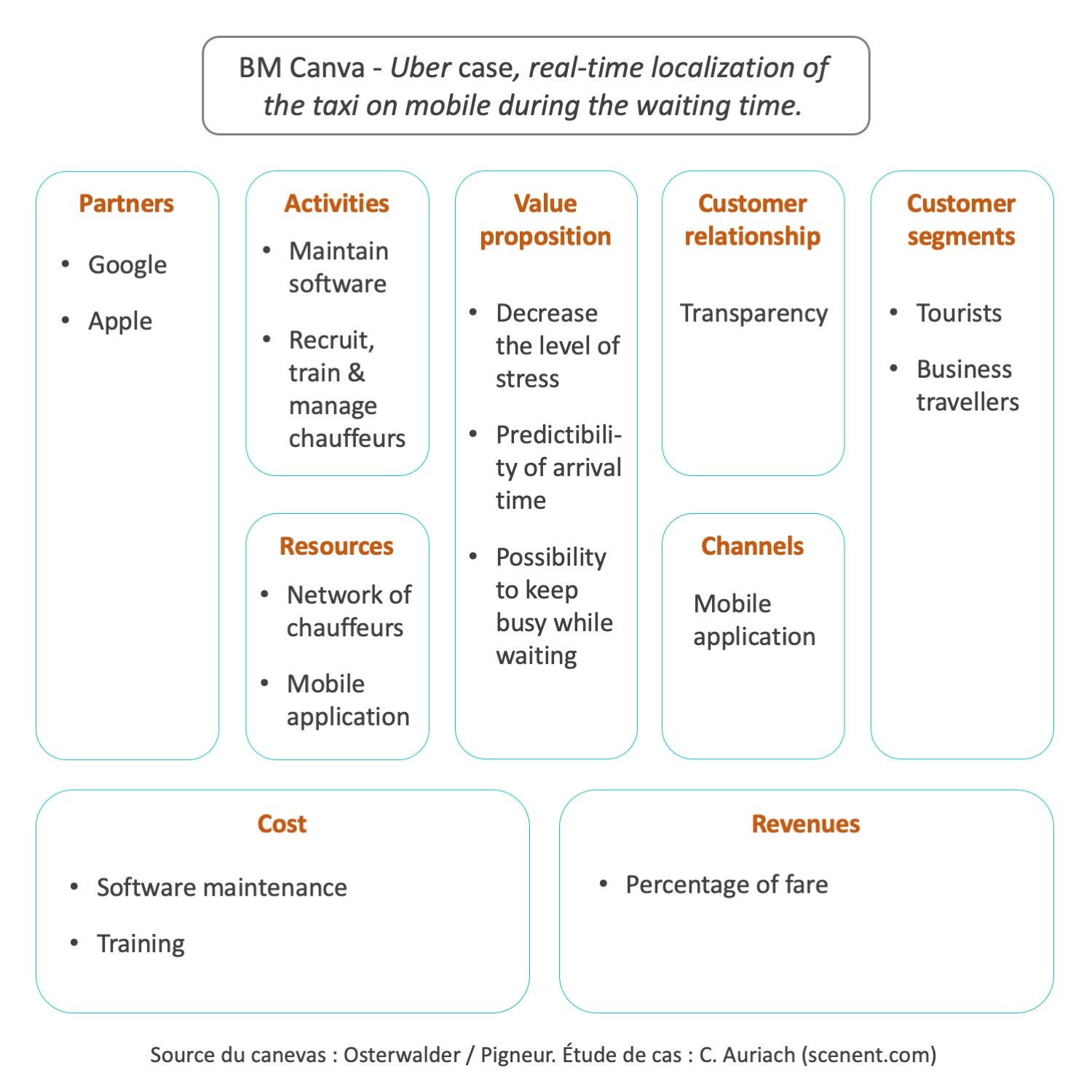

c) Zoom in on the operational and economic model: the Business Model Canva

08. Initial Dashboard

a) Highlight the key objective of a reporting process.

b) Identify promising market trends for the organization in question

c) Initiate a dashboard

09. IPM strategy

a) Understand the purpose of an IPM strategy

b) Define the IPM strategy

c) Plan next milestones for IPM strategy execution

10. Storytelling

a) Identify a bedrock of corporate stories and legends

b) Select stories with potential

c) Initiate the production of a collection of stories

11. Collaborative ecosystem

a) Position a target balance between internal innovation and open innovation

b) Prepare open innovation

c) Experiment open innovation

12. Initial communication plan

a) Framing the communication plan

b) Prepare the communication plan

c) Initiate the communication plan

Tasks

01. IPM vision

a) Identify and assign key roles

i. Identify the role of the Chief Innovation Officer.

ii. Identify IPM promoters. Qualify their roles.

iii. Characterize decision-maker, expert, project leader profiles.

b) Share a frame of reference for innovation initiatives

i. Know the differentiators of innovation projects.

ii. Define the success criteria of an innovation project.

iii. Define the criteria for focusing an innovation initiative.

iv. Define the types of problems that are the subject of innovation.

v. Confront a case study: the IPM vision of a pharmaceutical laboratory.

c) Give rhythm

i. Define the rhythm of production of visible steps on an innovation project.

ii. Define the pace of introduction of innovations.

iii. Formalize and share the result of group work.

02. Scope of application

a) Map the organization at the macro level

i. Appreciate the different cultures of innovation.

ii. Distinguish ideation, structuring and decision-making.

b) Qualify the innovation culture of each subset

i. List formal innovation processes.

i. List informal innovation processes.

ii. List examples of managerial initiatives promoting innovation.

iii. Analyze recent pivot decisions.

iv. Identify open innovation partnerships.

v. Identify examples of focused innovation projects.

vi. Identify examples of multipurpose innovation projects.

vii. Confront a case study: Pixar.

c) Revisit the cartography at macro level

i. Prepare for the collection of information in the field.

ii. Adjust the perimeter of the subsets.

iii. Formalize and share the result of group work.

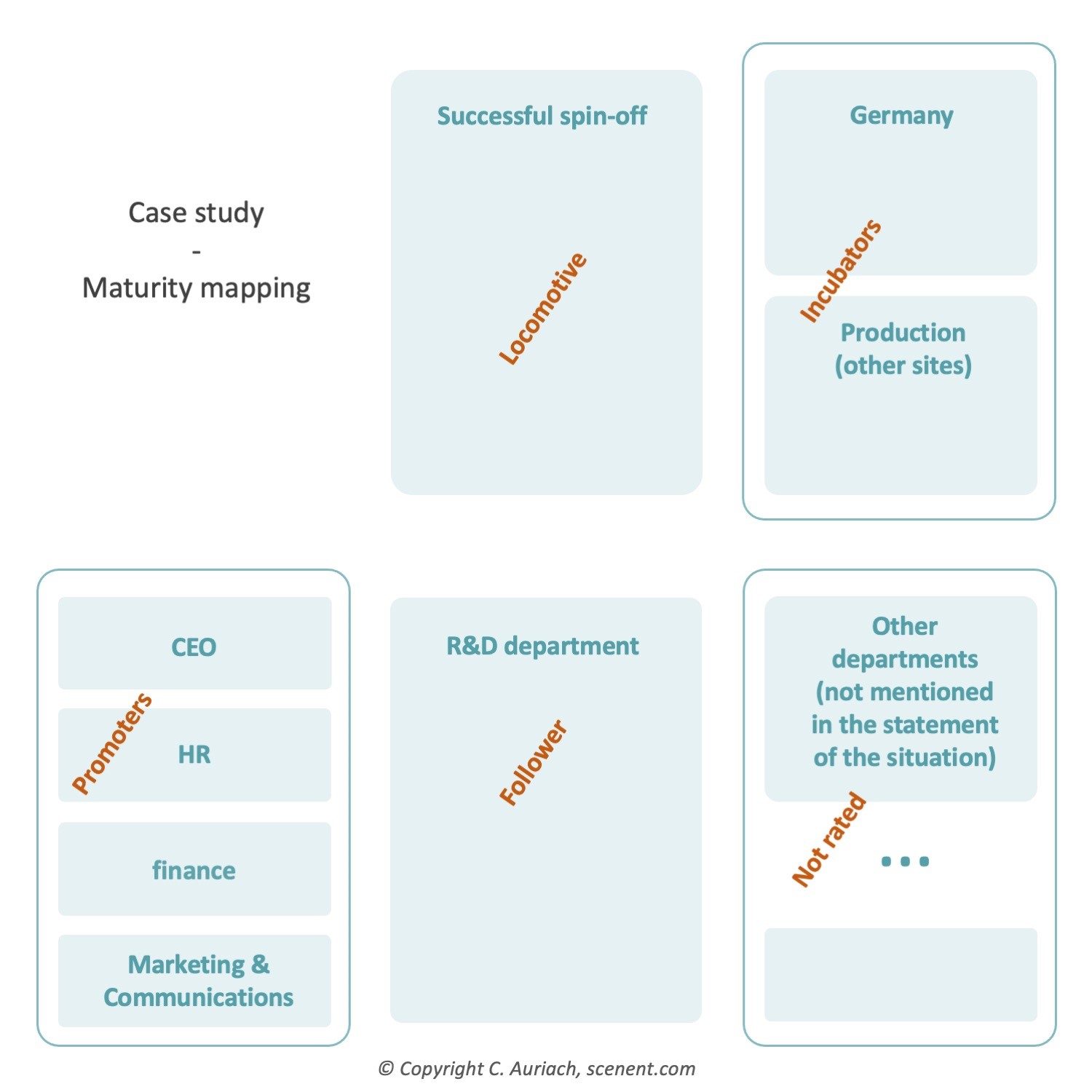

03. Mapping of maturities

a) Compare the as-is situation to known innovative business models

i. Familiarize yourself with the recommended evaluation model.

ii. Use the model to diagnose the as-is situation.

b) Establish a diagnosis

i. Give a maturity score to each subset.

ii. Formalize the diagnosis.

iii. Confront a case study: breakdown of the scope of application of IPM at a pharmaceutical laboratory.

c) Specify the diagnosis

i. Characterize the strengths of each subset.

ii. Characterize the improvement areas.

iii. Formalize and share the result of group work.

04. Cellular organization

a) Understand the situations conducive to the implementation of a cellular organization

i. Situate cellular organizations in organization theory.

ii. Understand 5 meta-rules of cellular organizations.

b) Adapt the principles of cellular organizations to the context

i. Select pilot projects.

ii. Identify the pivots operated on these projects.

iii. Identify the components of project blueprints.

iv. Identify the regulatory constraints applicable to these projects.

v. Measure the value created.

vi. Confront a case study: assess stock of fishes in the oceans.

c) Preparing for the experiment

i. Promote places of exchange for contributors to innovation.

ii. Make the link between cellular, learning and agile organizations.

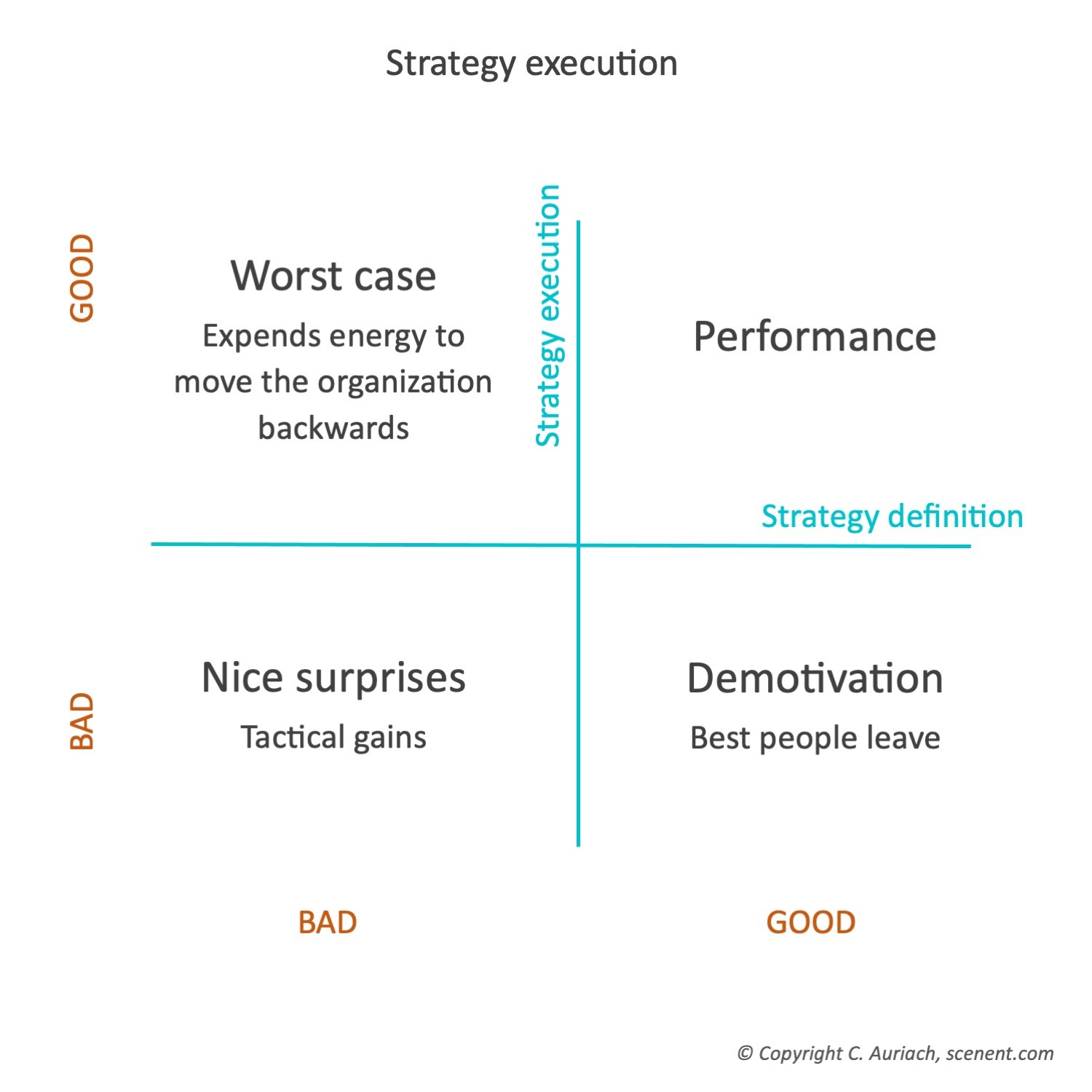

iii. Distinguish innovation strategy and tactics.

iv. Formalize and share the result of group work.

05. Collaborative tool

a) Choose a collaborative solution

i. Know the collaborative tools commonly used.

ii. Preselect a solution.

b) Customize the solution

i. Qualify the functionalities of the prospective collaborative solution.

ii. Analyze functional deviations from the target.

iii. Identify the functions of the common core.

iv. Identify differentiating functions.

v. Compare the solution to the culture of the organization.

vi. Facing a case study: consortium of 4 allied innovative companies.

c) Specify the key use cases

i. Describe information presentation formats.

ii. Describe the main use cases of the tool.

iii. Formalize and share the result of group work.

06. Network of Pioneers

a) Identify contributors potential

i. List outstanding questions.

ii. List the relevant interlocutors.

iii. Qualify the profiles of the interlocutors.

b) Anticipate collection of information

i. Qualify the networks of first-level interlocutors.

ii. Organize a survey.

iii. Confront a case study: contributors in a pharmaceutical laboratory.

c) Mobilize contributors

i. Anticipate future contributor roles.

ii. Formalize and share the result of group work.

07. Pilot portfolio

a) Visualize a portfolio target

i. Assess the situation of the existing portfolio.

ii. Set a critical mass target for innovative initiatives.

iii. Anticipate a targeted distribution of innovative initiatives.

b) Initialize a pilot portfolio

i. Identify candidate innovation projects.

ii. Frame candidate innovation projects.

c) Zoom in on the operational and economic model: the Business Model Canva

i. Understand the Business Model Canva tool.

ii. Confront a case study: Uber.

iii. Formalize and share the result of group work.

08. Initial Dashboard

a) Highlight the key objective of a reporting process.

i. Make the link between reporting and the decision-making process.

ii. Identify decision-making situations.

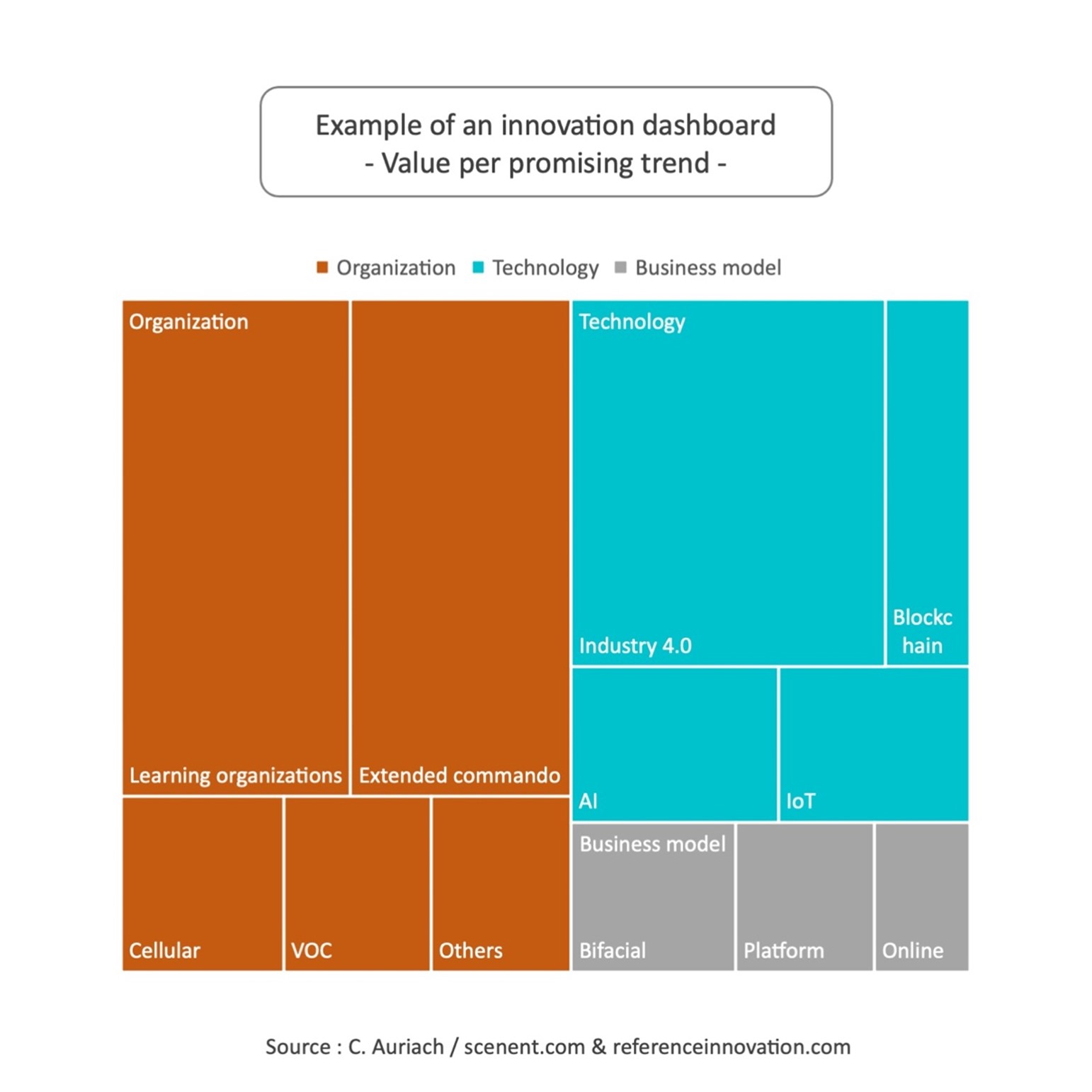

b) Identify promising market trends for the organization in question

i. Confront existing dashboards.

ii. Identify a first set of promising trends.

iii. Order trends according to their store of value.

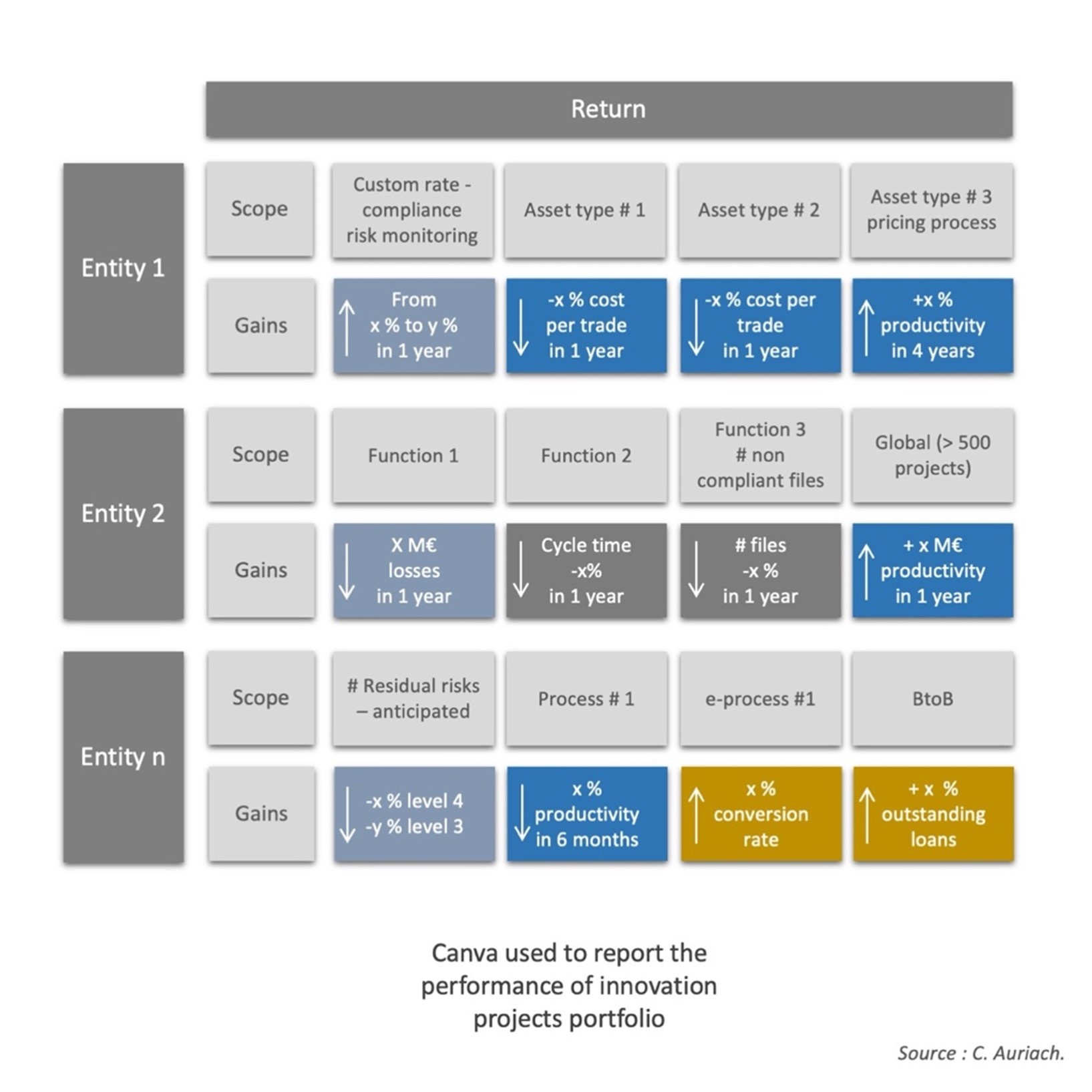

iv. Confront a case study: the store of value of a financial group’s innovation portfolio.

c) Initiate a dashboard

i. Assess the level of progress of projects.

ii. Align projects with the IPM vision.

iii. Measure the store of value of innovation projects.

iv. Identify the need to pivot innovation projects.

v. Formalize and share the result of group work.

09. IPM strategy

a) Understand the purpose of an IPM strategy

i. Understand the differences between IPM strategy and innovation strategy.

ii. Visualize the IPM process.

b) Define the IPM strategy

i. Confront typical transitions from one level of maturity to another.

ii. Define the conditions for success.

iii. Confront a case study: Apple and connected glasses.

c) Plan next milestones for IPM strategy execution

i. Formalize the objective of increasing the level of maturity.

ii. Plan the horizon for reaching the next level of maturity.

iii. Identify strengths and obstacles.

iv. Develop a strategy for overcoming obstacles.

v. Formalize and share the result of group work.

10. Storytelling

a) Identify a bedrock of corporate stories and legends

i. Practice writing a story.

ii. Know the different forms of innovation storytelling.

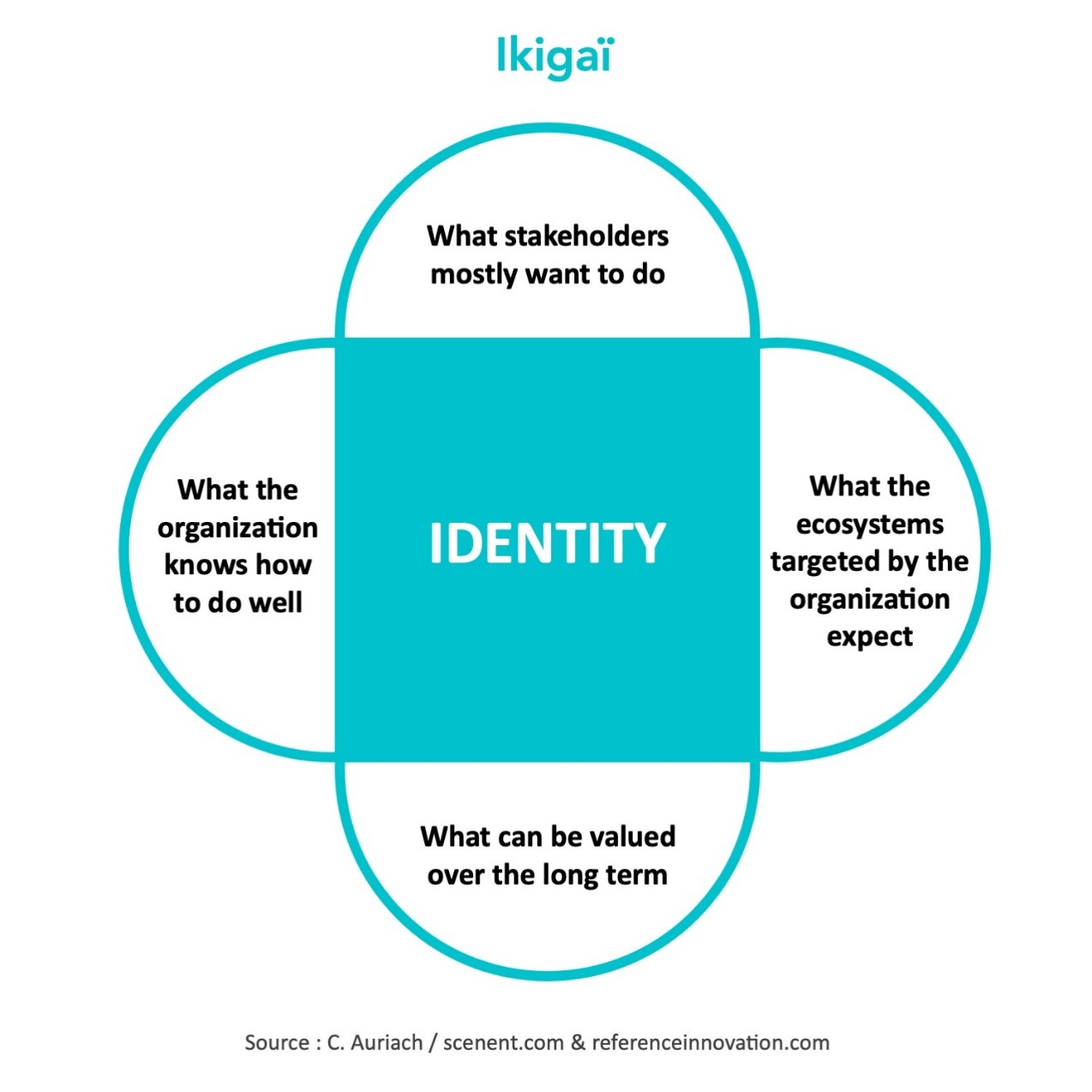

iii. Characterize identities and styles of innovation.

b) Select stories with potential

i. Choose past or future innovation stories.

ii. Justify this choice.

iii. Confront a case study: Logistikos.

c) Initiate the production of a collection of stories

i. Apply the storytelling canvas adapted to an innovation context.

ii. Position the stories according to the 4 Ikigai axes.

iii. Vary the angles of the stories.

iv. Formalize and share the result of group work.

11. Collaborative ecosystem

a) Position a target balance between internal innovation and open innovation

i. Compare internal and external solutions.

ii. Shape recurring innovation processes of a technological or scientific nature.

iii. Appreciate the potential of an open innovation process.

b) Prepare open innovation

i. Capitalize knowledge.

ii. Sort knowledge.

iii. Select assets with potential.

iv. Confront a case study: the Valmido project.

c) Experiment open innovation

i. Identify sources of strategic information.

ii. Probe internal and external sources.

iii. Consider using open innovation platforms.

iv. Characterize a relational network in an innovative ecosystem.

v. Formalize and share the result of group work.

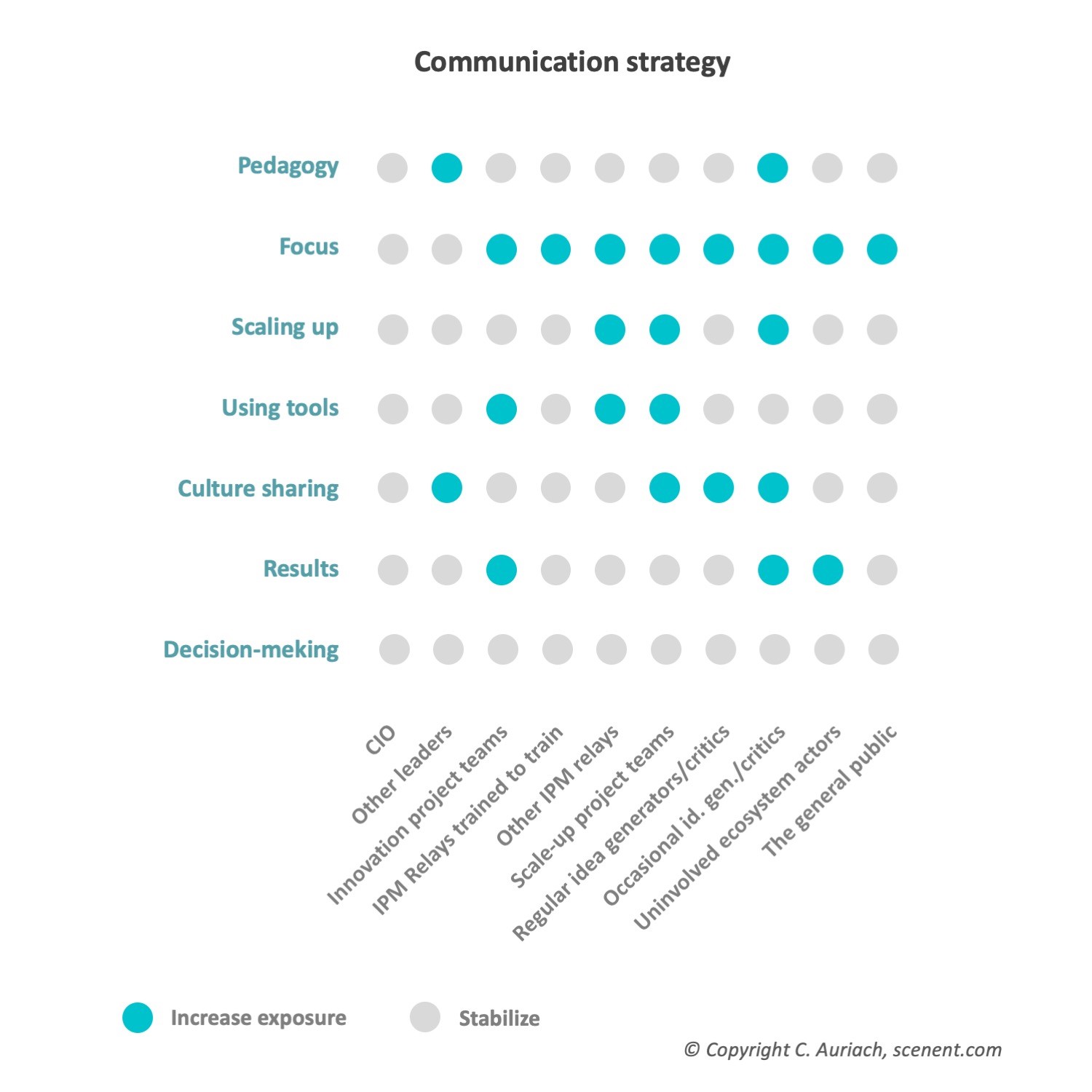

12. Initial communication plan

a) Framing the communication plan

i. Identify communication needs.

ii. Focus its communication on strategic themes.

b) Prepare the communication plan

i. Decline a 6 Ws & an H process. Why, whom, who, when, where, what & how.

ii. Confront case studies: in a banking group, at a major software publisher.

c) Initiate the communication plan

i. Build a communication strategy.

ii. Represent a table of correspondence between reasons for communicating and communication targets.

iii. Set a goal to stabilize or increase exposure.

iv. Formalize and share the result of group work.

Introduction

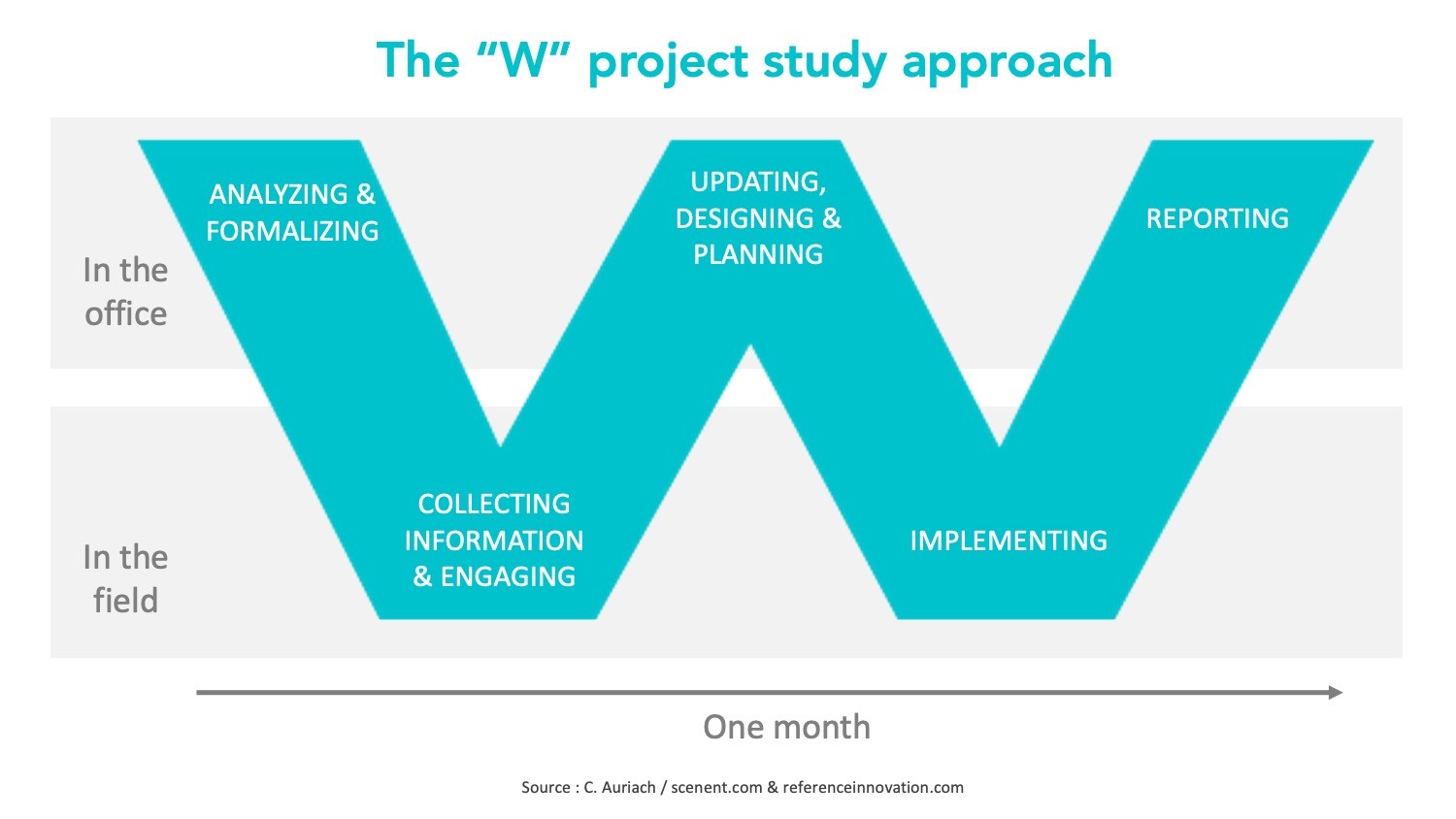

IPM scope definition

The first of the 48 stages of the deployment of the IPM approach is devoted to the breakdown of the scope of the organization into coherent subsets from the point of view of the culture of innovation. Each subset presents a certain homogeneity in terms of assets and challenges to be met to stimulate the performance of the portfolio of innovative initiatives. To be able to draw this cartography at a macroscopic level, the acquisition of a certain number of notions is necessary: what is an IPM vision? How to assess the maturity of an IPM process? How to co-construct a heritage of stories and legends in order to feed a participatory communication approach? What is Open Innovation? What is the difference between an IPM strategy and an innovation strategy? How to identify candidate pilot innovation projects for inclusion in a portfolio? How to measure the performance of innovation, according to which processes and with which tools? Who are the natural contributors to innovation? How to mobilize them? What is a cellular, learning and agile organization?

Workshop participants address these questions with the support of course manuals and associated exercises, as well as by bringing their knowledge of their field. The most useful contextual information during the workshop is as follows (if it is not available before participation in the workshop, do not panic: it will be collected between the first two workshops; this information is not essential prerequisites but allow you to become familiar with the vocabulary and practices of your organization in terms of innovation, whether the maturity of the IPM process is non-existent, low, advanced or intermediate):

• Knowledge of ongoing innovation projects: make a clear distinction between an innovation project and a project. An innovation project differs from another project in particular by the hope of leading to a unique capability on the market or in the ecosystem considered. An innovation is carried by a single actor, whereas an offering or a process that is only differentiated, and not innovative, is carried by a small club of actors, with one or more leaders and followers.

• Knowledge of stories of innovation projects, successes and failures, and the apparent or proven reasons for their conclusions: try to understand the methods used to analyze successes and failures, ask yourself the question of possible improvements.

• Collaborative tools used within the organization: are innovation-specific tools such as qmarkets, craft.io, planview or ideascale already used? Are other more generic tools such as Microsoft Teams, Microsoft Sharepoint, the Atlassian Confluence suite, the Google Meet + Google Docs suite, Dropbox Business or Slack also used to support innovation ? For what uses? If there are guidelines for use or constraints on use, try to obtain them. If similar tools are used, the same questions arise.

• Innovation dashboards: are there specific reporting processes for innovation projects? What indicators are monitored and why? Are these indicators reliable? What decision-making processes do they feed? Who is responsible for it?

• Potential contributors to the IPM approach: who are the project managers or project directors, official or informal, involved in innovative approaches? Who decides to invest in innovation? Who promotes innovation the most, by their actions or by their communication?

This information can be useful but should not be too detailed before the workshop, in order to maintain the spontaneity necessary for co-creation. Because deploying an IPM approach is in itself an opportunity to innovate, if only to reveal the potential of the organization concerned.

Pointing to the key innovation levers (Photo by Simon Lee on Unsplash)

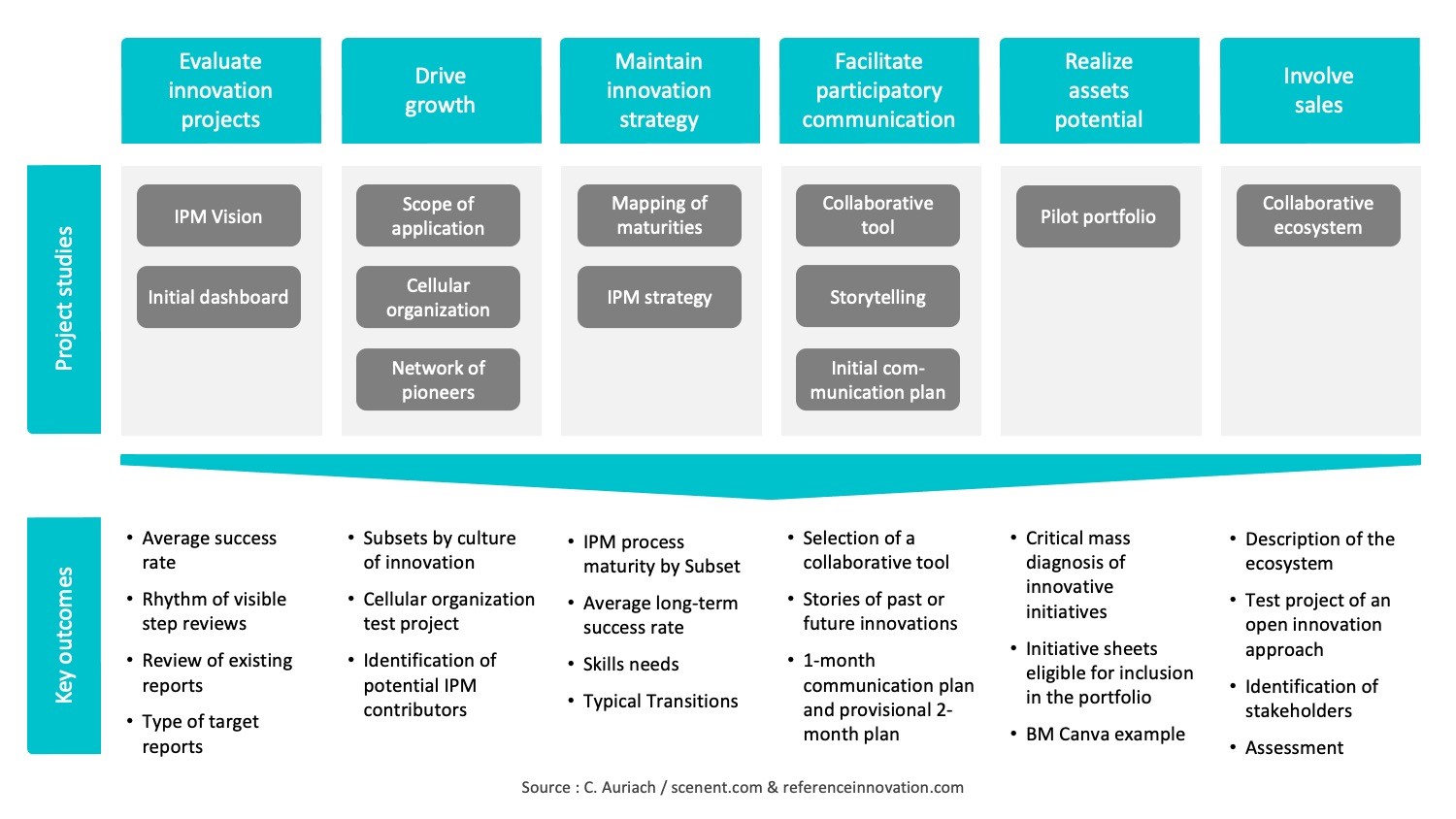

Context of IPM scope definition

This High-Performance Innovation program is designed to provide companies, public bodies or non-profit structures with a state-of-the-art innovation performance management process. Frequently updated, it takes place over a period of 4 years, the typical duration of a transformation into an innovation-driven organization from a few hundred people to several hundred thousand. By participating into this program, you will experience both highly creative times and times for making dreams come true. At the end of the day, you will have deployed a state-of-the-art innovation portfolio management process in your organization. You will break it down into six key dimensions: maintaining the innovation strategy, realizing the potential of assets, facilitating participatory communication, evaluating innovation projects, involving sales and driving growth.

• In one year you will have deployed the approach on a pilot scope.

• At the end of the second year you will have customized your process in a variety of diversified contexts.

• The third year will be dedicated to transformation at scale, reaching all dimensions of the organization.

• Then, during the 4th year, it will be a matter of maintaining the momentum through a dynamic continuous improvement phase.

This first workshop in a series of 48 is dedicated to establishing a vision and strategy for managing innovation performance. It mobilizes decision-makers, project managers and contributors to innovation to help manage the portfolio of innovation projects within their organization.

Here are the key steps:

• IPM Vision: identifying the conditions of innovation performance relevant in the context of the organization under consideration.

• Scope of application: adapting an innovation portfolio management approach by subset of the organization.

• Mapping of maturities: knowing itself and appreciating its potential, thanks to a maturity scale on 12 levels.

• Cellular organization: fostering flexibility, fluidity of the process of creation, disappearance and transfer of teams dedicated to subsets in according to their constantly reassessed potential.

• Collaborative tool: sharing know-how in terms of Innovation Portfolio Management thanks to a quickly operational collaborative environment.

• Network of pioneers: mobilizing experts capable of answering outstanding questions relating to past innovation projects, in particular the factors of success and failure of these initiatives.

• Pilot portfolio: detecting projects encountering significant difficulties, or for which the need for pivoting emerges.

• Initial dashboard: defining essential characteristics of an innovation project, not only in terms of what defines it, but also and above all in terms of its potential for creating distinctive value.

• IPM Strategy: creating the conditions for raising the value generated by innovation initiatives within an organization.

• Storytelling: promoting stories of innovation on a variety of channels, oral, written, audiovisual, virtual and physical.

• Collaborative ecosystem: looking outside. How could the impact of innovation be multiplied by having recourse to external collaborations?

• Initial communication plan: focusing on a selection of stories collected during and after the first workshop.

This first workshop introduces participants to the worlds of IPM (innovation portfolio management), cellular organizations and collaborative ecosystems in a progressive, step-by-step manner. The typical training audience is recalled, made up of leaders, managers and experts called upon to drive innovation within their organization. The link is established between the position of the participants, their challenges, their responsibilities, their natural scope of intervention, their mission, their objectives relating to the dynamics of innovation and the potential and proven contributions of IPM. Emphasis is placed on the need to create a balance between the relative influence of creative talents and structuring talents, by analyzing an example of an innovative company known for its recurring successes. In particular, the notions of focusing and pivoting are closely studied.

IPM vision and innovation culture

The first outcome of the workshop is the development of an IPM vision, which must be personalized according to its scope of application. Participants are then invited to break down their organization into coherent subsets from the point of view of the culture of innovation, according to an iterative process. They start by choosing a first subset using a suitable set of characteristics, then a second, and so on, until they cover the entire organization. Each participant does this exercise on his or her known scope of intervention and is confronted with the points of view of the other participants.

A variety of existing innovation cultures (Photo by Mark König on Unsplash)

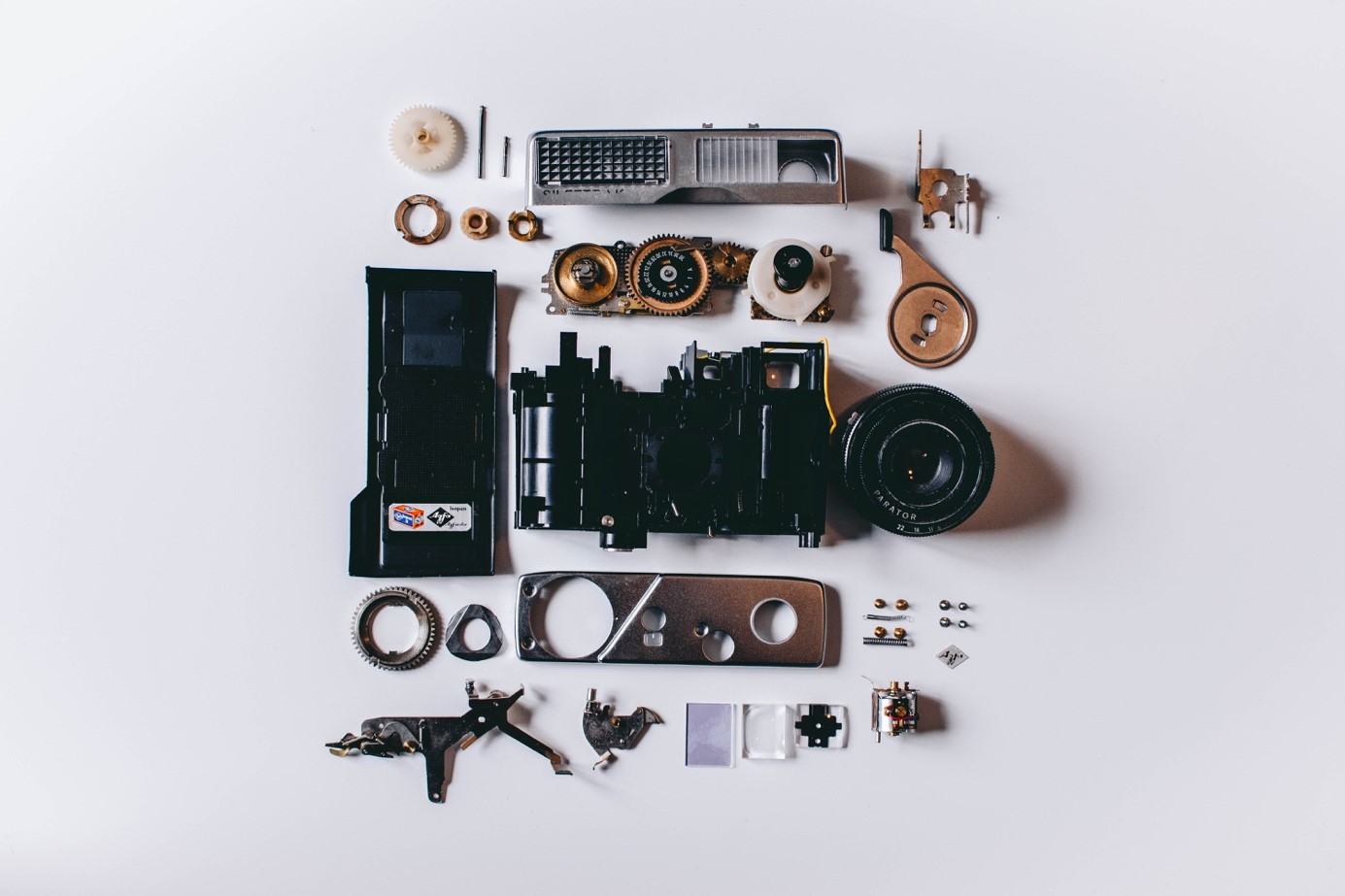

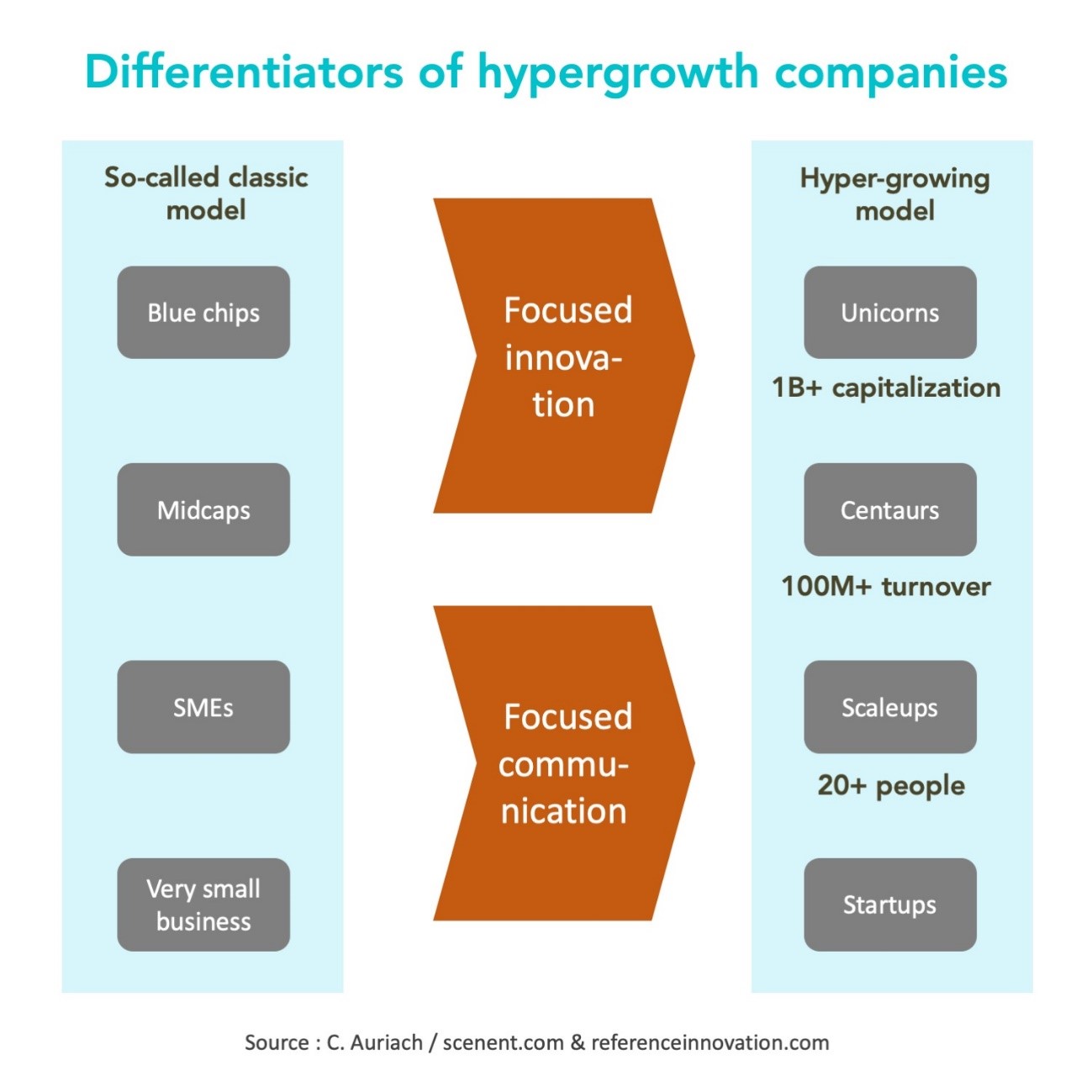

The IPM approach is eminently transversal and concerns all the functions of the organization. It applies both to departments exposed to the outside and to internal departments, to business units and to support functions, to recurring operations and to the management of exceptions. Each participant comes with their own experience of innovation and the context in which they are or will be responsible for promoting it and making it more manageable. Because a key challenge is its manageability. However, an innovation initiative is not managed like an initiative of imitation or reinvention. In this regard, realizing that a project, seen as a contribution to a transformation, consists either of innovating, of imitating, or of reinventing, is already a step forward. Knowing when to innovate (i.e. being creative while managing uncertainty and risk more than schedule and budget) and when to imitate (i.e. do what has already been done elsewhere avoiding the mistakes of the pioneers) is a key performance factor. It requires breaking down the issues addressed by the initiatives at the right level of granularity, avoiding over-practicing hybridization between innovation and imitation so as not to generate excessive complexity. As for reinvention, it is clearly to be avoided, which presupposes organizing functions for monitoring and sharing best practices. This last capability is also one of the key differentiators of hyper-growing innovative organizations such as unicorns ($1 billion in capitalization) or centaurs ($100 million in revenue). Their rate of reuse of external assets, for example that of open-source code integrated into a digital solution, advanced electronic components in a miniaturized device or pre-existing processes in the construction of a new service offering, has no equal but their level of focus. Reuse and specialization are then two other strong points of these structures, which the major established players are increasingly drawing inspiration from to identify business units or functions that are candidates for hypergrowth. Reuse avoids wasting energy reproducing what has already been done, thus allowing you to focus on a specialty. In summary, creating value by innovating amounts to establishing a quality, efficient watch, to assembling existing reusable components and to creating new ones associated with them, these three actions being carried out in any order. Indeed, nothing prevents starting by creating a new capability and asking the question of its assembly a posteriori, provided that at each stage a constantly updated alignment with the expectations of the market or the ecosystem is the basis of any structuring decision. To achieve this, it is necessary to stimulate creativity at all levels, to scrutinize and evaluate the right trends, to master the composition of its portfolio of innovative initiatives, to train the persons who are managing it, to invest wisely, to make the right informed decisions at the right pace, to know your assets with potential, to communicate at the right time with the right content for the right targets, among other typical tasks carried out by contributors to innovation. In short, pave the way for the deployment of IPM processes.

Scope of application

The IPM vision benefits from being shared, on the one hand because exposure to other eyes and other ears makes it possible to raise new key questions, on the other hand because it must be transformed into an action plan. However, because the various components of a company do not all have the same history in terms of innovation, because they do not always share the same imperatives of speed, flexibility, performance or quality, their relation to IPM may be different. It is therefore necessary to adapt an IPM approach to each of them, by finding the right level of granularity: neither too fine for the whole to remain controllable, nor too coarse to remain aligned with the reality of the field. The scope of application of the IPM is therefore most often broken down into distinct geographical or functional entities, each of them presenting a good level of homogeneity in terms of culture of innovation. For example, a research and development department generally has a tradition of leading innovation projects of its own, different from the approach of other departments less focused on the subject. The work of identifying the subsets of the organization, consistent from the point of view of their innovation dynamics, is primarily the responsibility of management. Typically, pairs made up of executive committee members and innovation project managers, steering committee members and innovation project managers, or leaders at various levels involved in innovation projects can contribute to this reflection upstream, before confronting it with other interlocutors to complete the collection of useful information for establishing the personalized scope of application of the IPM.

Breaking down the application scope of IPM (Photo by Samson on Unsplash)

By culture of innovation, we mean a set of common practices, processes and places of co-creation, collaborative tools, methods of project management or arbitration between competing avenues of resolution, examples given by the management of encouraging creativity via highlighting of promising initiatives or financing of prototypes, propensity to open up to external partnerships from the upstream phases of the development of an innovative product or service, all themes that will be developed in course manual 2 – scope of application.

If the organization has already been broken down into SBAs, or Strategic Business Areas, each operating in its own competitive universe, the division into coherent subsets from the point of view of their culture of innovation can be different. An innovation can cause a change in the competitive universe obtained, or even its creation. The first smartphone had no competitor when it was released, as did the first electric car, the first virtualized banking service or the first contract authenticated on a blockchain. In a less disruptive logic and on a different scale, the same was true of the first service for creating e-commerce catalogs or the first use of drones to assist firefighters in their work. The products and services offered by an SBA are presented to the market, users or beneficiaries using the same strategy. On the other hand, a coherent subset from the point of view of the culture of innovation can very well lead to the emergence of products and services presenting a great heterogeneity of economic and operational model. There is no a priori prior to the conduct of innovation initiatives hosted by such a subset, which has the advantage of not curbing the creativity of the parties concerned.

Nevertheless, it is possible that a large number of different innovations, with similarities in their development process, are made available each year on the market or in an ecosystem by one or more subsets. In this particular case, this significant rhythm is linked to the scaling up of the innovation process itself, with a concern for the profitability of specific means such as a test bench, a supercomputer, a laboratory, a device for scientific experimentation or a resource-intensive process. Here the set of constraints imposed by an exceptional investment is compensated by the variety of its potential fields of application. These models are generally the prerogative of advanced innovative dynamics of a technological or scientific nature, capable of introducing dozens of patented novelties each year at the level of a single sub-assembly. This is the case, for example, of a highly robotized electronics laboratory producing prototypes of printed circuits with multiple potential uses.

On the other hand, there are few or no examples of organizational, behavioral, commercial, environmental, procedural, relational or societal innovations, whether or not associated with digital solutions, subject to the combination of a high level of specialization and a high rate of novelty introduction. These are generally more diverse in nature. This leads us to take a closer look at these typologies of innovation, which are at the heart of service organizations and in industries not dependent on a rapid pace of innovation. Given the growing share of the tertiary sector in the creation of global value (about three quarters of gross domestic product in the most developed countries and a little less than half in developing countries), they underpin the vast majority of initiatives managed in an innovation portfolio, objects of the deployment of the IPM process. They therefore influence the culture of a growing number of organizations, or rather subsets of these organizations. As much as it is natural to consider filing a patent to protect an innovation of a scientific or technological nature, it usually proves difficult to achieve this in another field: it is necessary to prove the originality of a process and its anteriority among a large number of potentially competing situations, without being able to rely on a tangible material basis. Indeed, a process of an organizational, behavioral, commercial, environmental, procedural, relational or societal nature, associated or not with digital solutions, above all manipulates information where a technological process above all manipulates matter (with the exception of information technologies underlying the digital solutions here). And information is more changeable, less palpable and less stable than matter. In this regard, the same reasoning applies to innovations and to process optimization or continuous improvement projects: a solution that deals with information is less stable over time than a solution that deals with matter. So highly specialized innovation processes in a technological or scientific field, manipulating stable matter, are theoretically capable of producing results at a more sustained rate than less specialized processes manipulating changing information. But the former are by definition less numerous than the latter. In reality, the majority of innovations create processes that are difficult to protect, pushing their promoters to protect the specificities of their brands and models instead. Communities of beneficiaries of innovations, users or customers, also provide effective protection, especially if they are particularly committed and loyal. Les différents réseaux sociaux, généralistes ou spécialisés, privés ou publics, largement déployés ou confidentiels, en fournissent un exemple patent. Their innovations are of a relational, societal, behavioral, commercial, procedural and organizational nature, each in their own way and above all in the way desired by their respective communities: young, old, passionate, instant video enthusiasts or other personae.

Splitting the landscape (Photo by ddp on Unsplash)

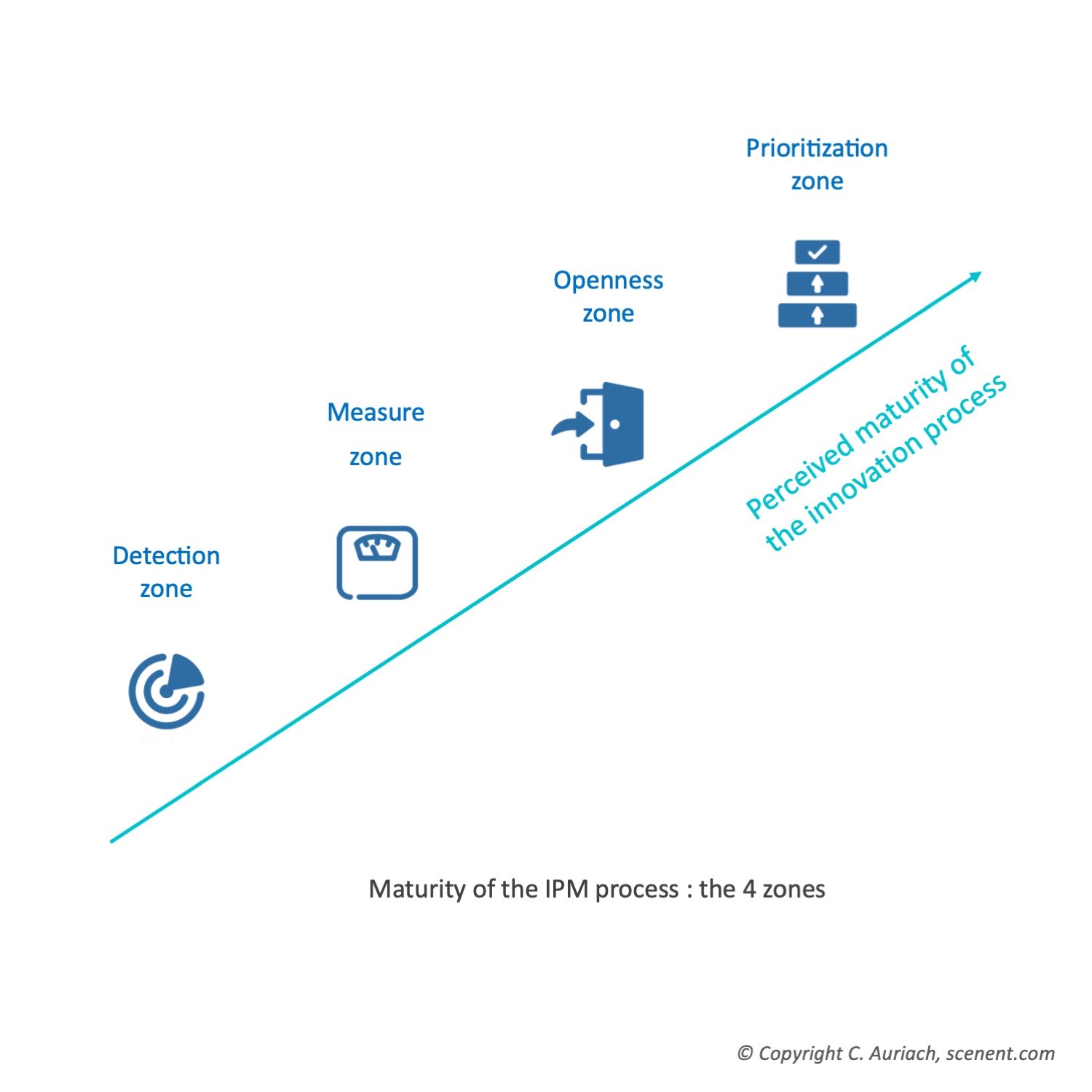

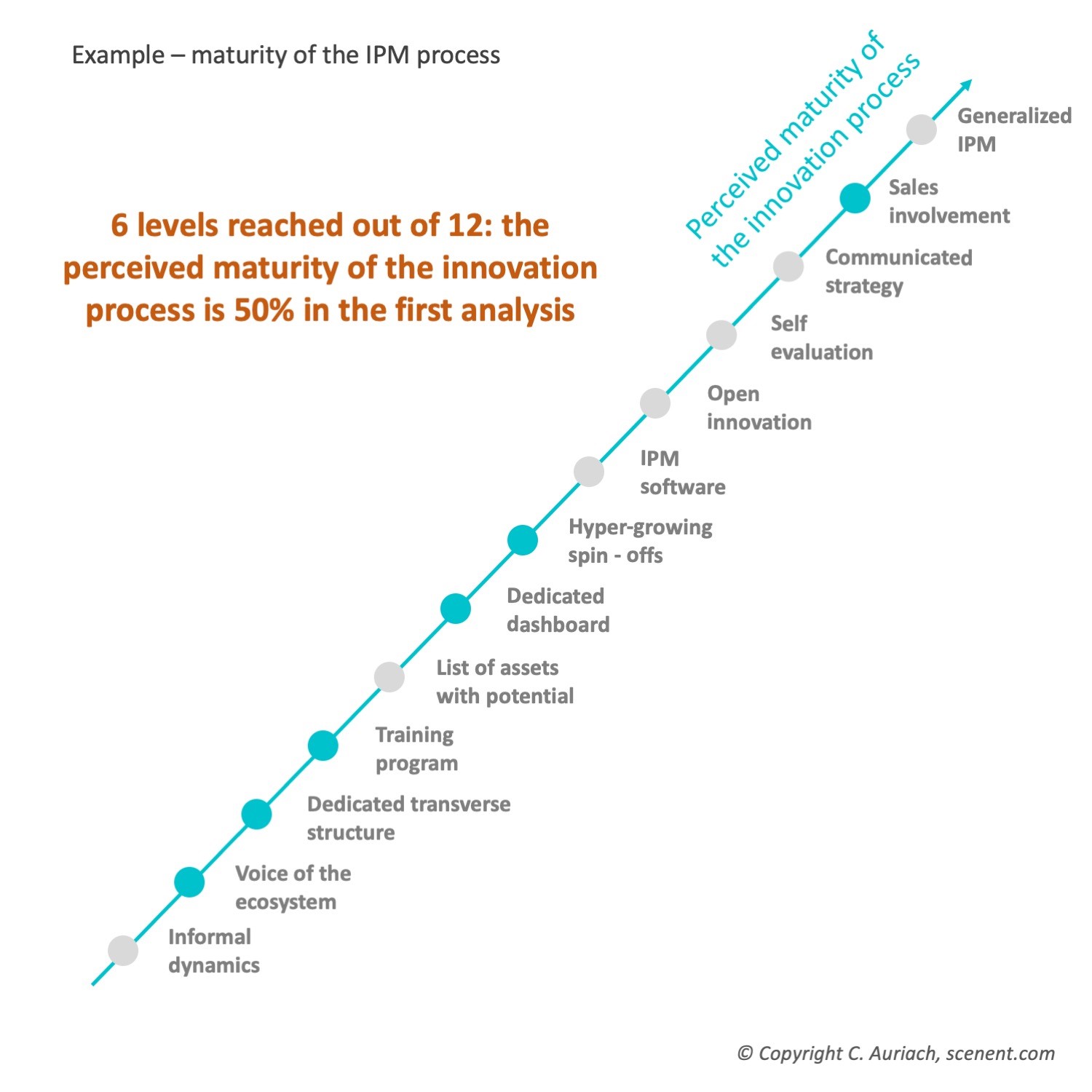

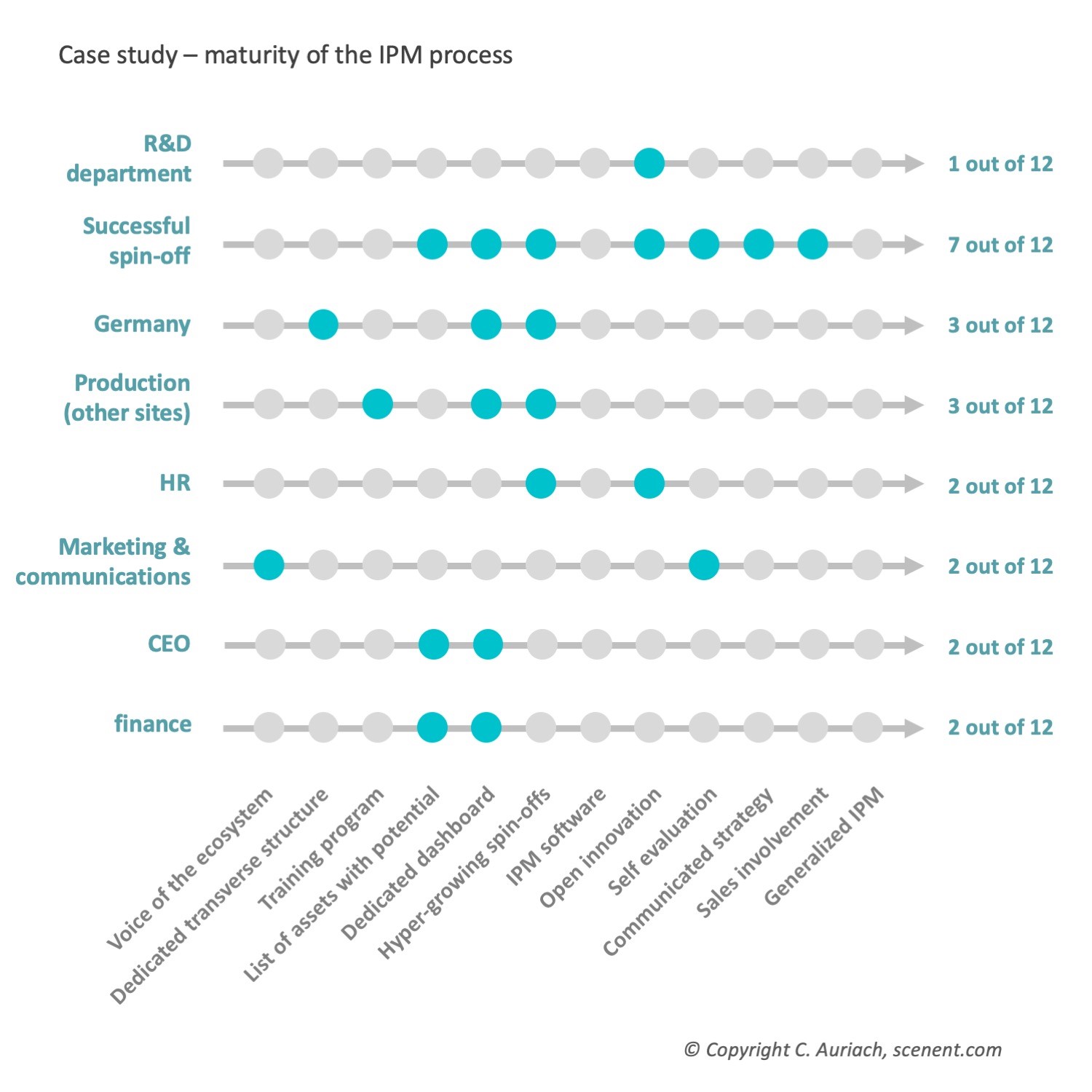

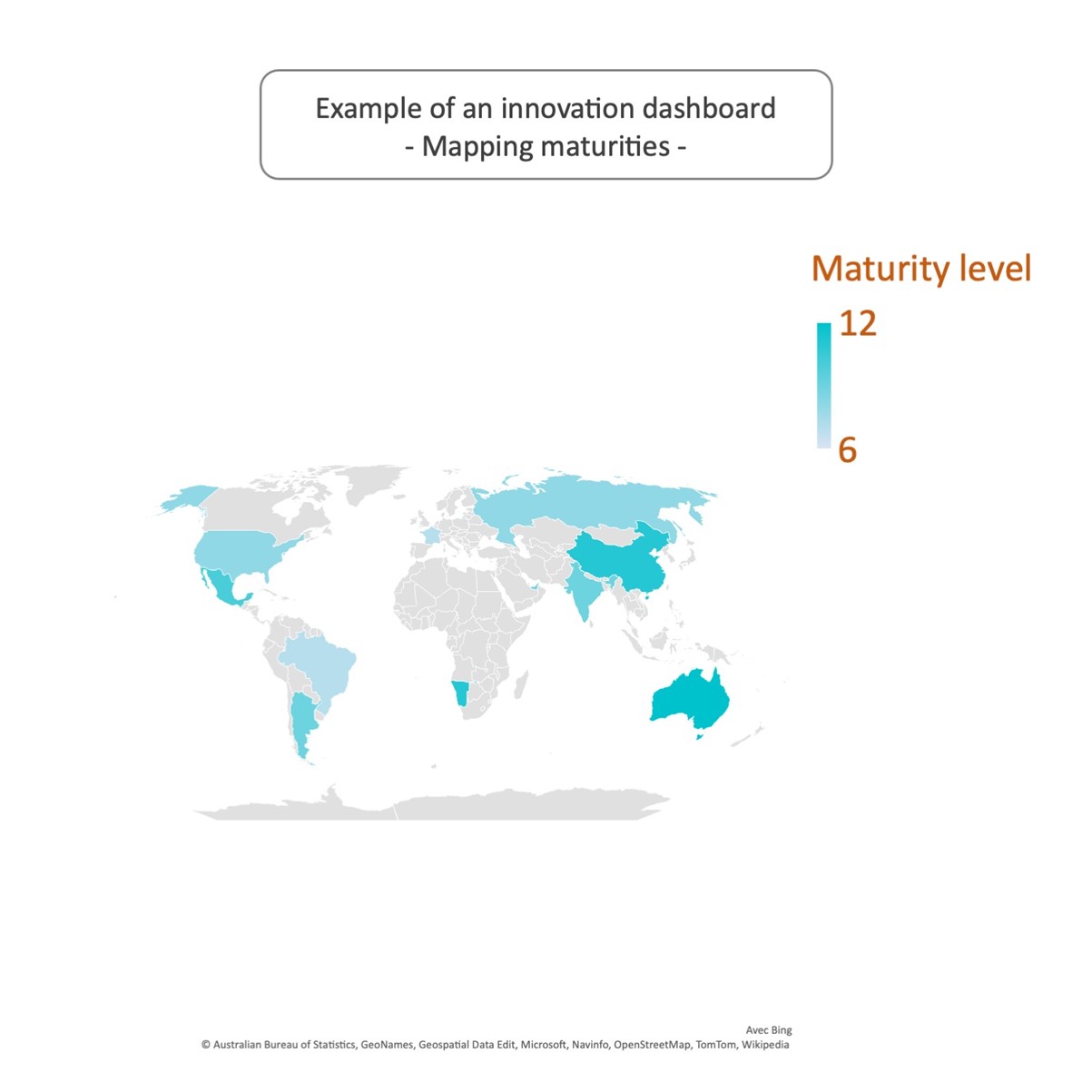

Mapping of maturities

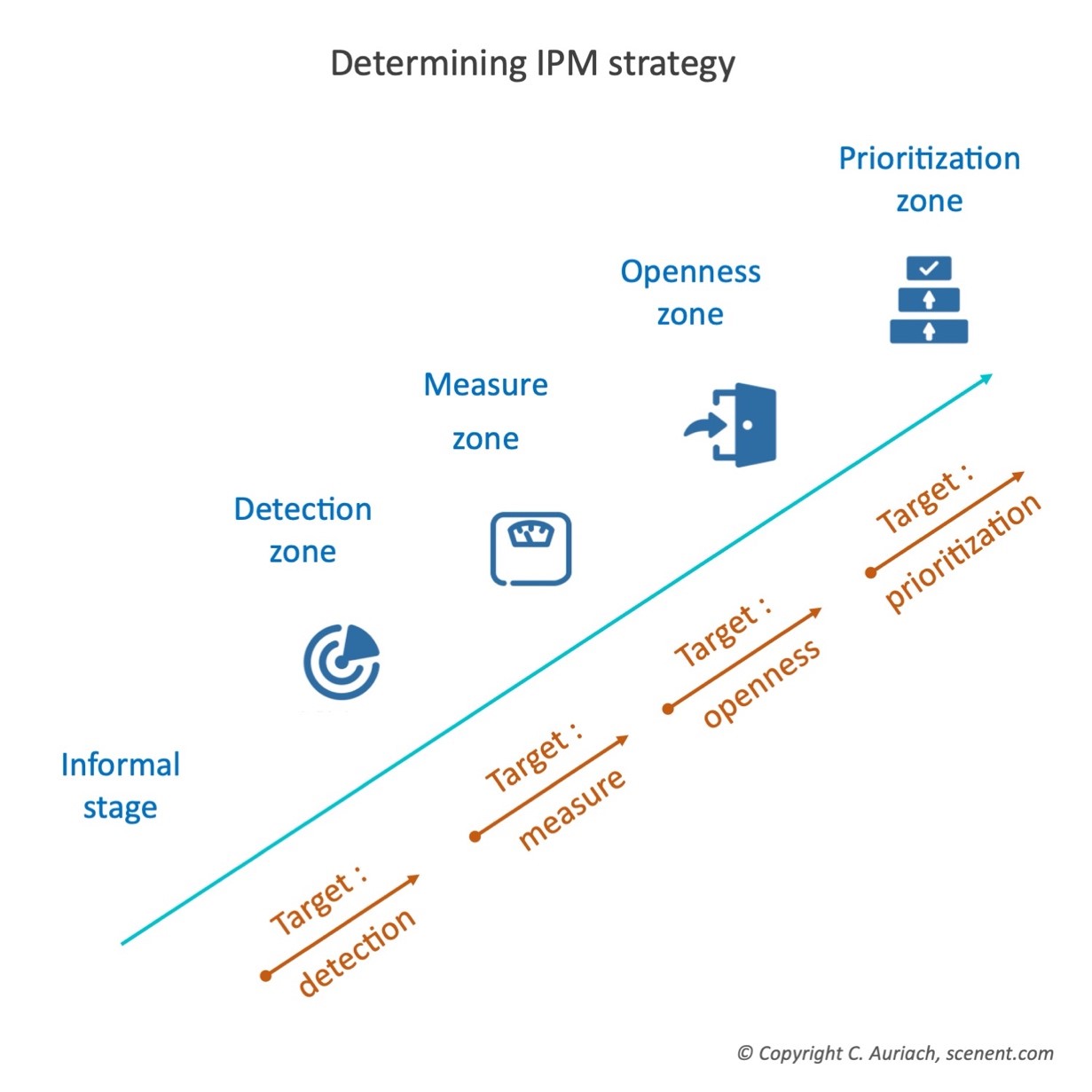

Each subset of the organization thus identified gains from knowing itself and appreciating its potential. This depends on the maturity of its innovation dynamic, which can be measured using a scale of 12 levels, organized into 4 levels of 3 levels each. The first stage relates to the detection of innovation opportunities: are the detection and promotion of ideas and innovative projects with potential favored by the culture in place, or by observable initiatives in the field? Is there a need to provide know-how in this area, or even to propose a virtuous process? If such a detection and promotion capability is operational, widely deployed and effective, the subset can be evaluated at the level of the second stage, which concerns its capacity to measure the impact of the innovation: are there appropriate innovation performance indicators? Are they relevant and useful? Is their definition simple and shared? Are the processes for generating these indicators known and upgradable? Then the third stage relates to the level of openness of the sub-assembly to the outside, to its propensity to innovate by sharing know-how and by practicing cross-fertilization with external actors. Finally, the fourth level characterizes the subgroups that have implemented an agile capacity to prioritize their innovation projects, with rapid frequency, by being very connected to an internal and external ecosystem of witnesses from the targeted markets. Positioning yourself on this scale and aiming for the next level constitutes a unifying project capable of mobilizing the right people, project managers and directors of innovation projects, innovation leaders, functional and technical experts potentially involved, salespeople and communicators, decision makers.

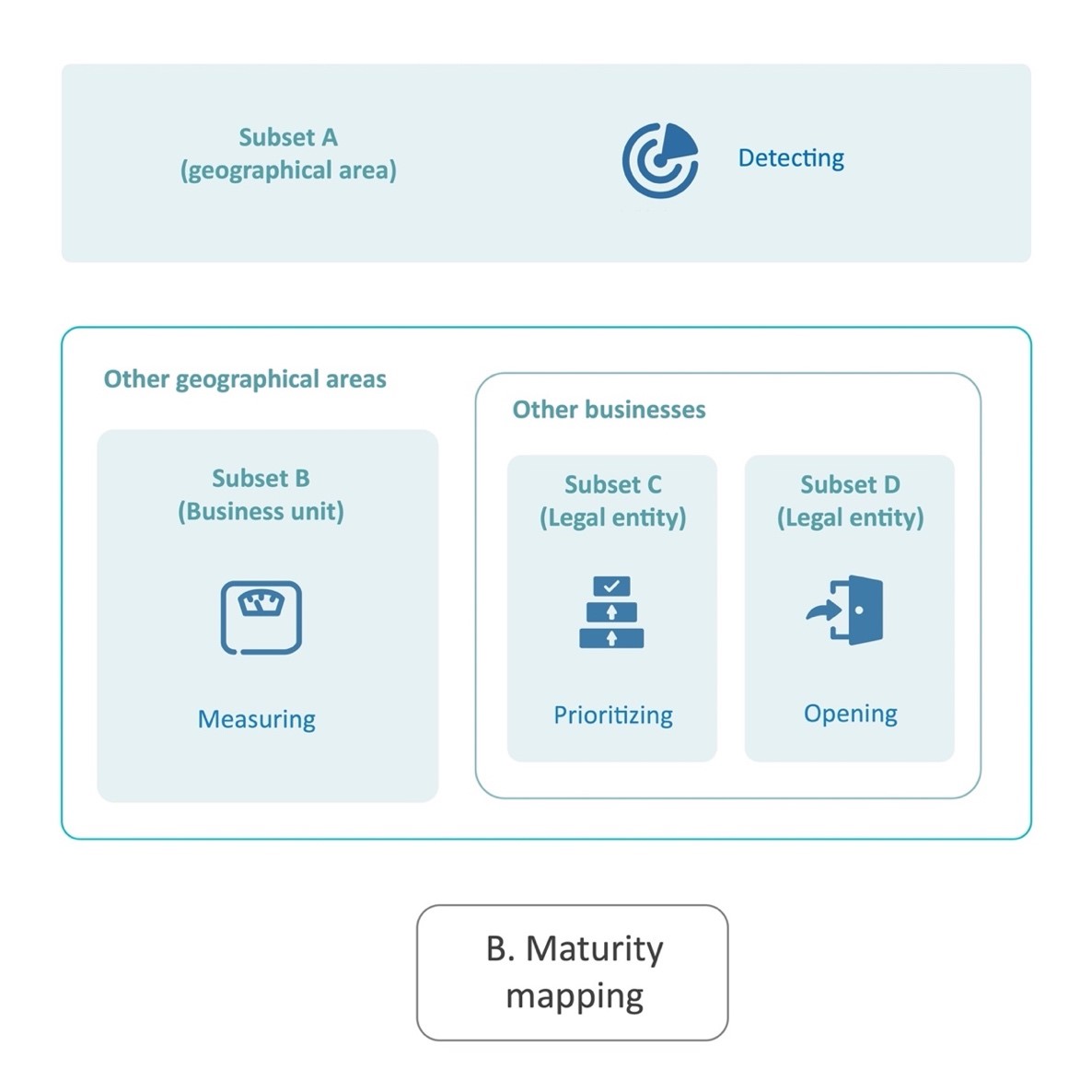

A map of maturities (see example on figure B. below) provides an overview of the situation of the organization from this point of view. In the example below, we find a geographical unit at the “detection” level, i.e. on this perimeter the key issue consists in maintaining the process of revealing assets with potential held by the organization, or by accessible partners, and to eventually become capable of realizing this potential and measuring the associated value creation. Knowledge of an asset with potential in no way prejudges the problem – solution path pairs that will define the initiatives entering the innovation portfolio. If this asset is a distinctive, known and characterized skill, this does not a priori constrain the nature and the objective of an innovation project exploiting this asset. This seems less true for a building or a machine, even if the diversion of use is a process of innovation frequently encountered and at the origin of many successes. A typical example is provided by the express reconfiguration of cutting, welding and shaping machines usually used to produce veils or clothing, with a view to supplying protective masks against Covid 19 on a large scale. This has also caused the appearance of improbable shapes and colors that can bring either to smile, or to ecstasy in front of so much creativity. Beyond the dramatic nature of the underlying health crisis, a number of assets with potential were revealed on this occasion, from the production lines for masks to new logistics circuits, including systems for monitoring the progression of the pandemic or ways to accelerate clinical studies of vaccines without abdicating their necessary harmlessness.

A geographical unit forming a coherent subset from the point of view of the culture of innovation can be a country, a region, a continent, a city or a very localized site. The granularity of the unit in question is not dictated by a general principle but by the originality of its innovation process, whether it is deemed efficient or not. Thus in figure B, subset A is a geographic entity exhibiting such homogeneity. On the other hand, the other subsets, still within the framework of this example, are defined either by the scope of a business unit or by that of legal entities. The criterion of homogeneity of innovative approaches remains the same. It simply corresponds to contours of a different nature. If one of the legal entities has trained all of its staff in the challenges of its digital transformation thanks to a highly personalized online role-playing game adapted to its business, it has created a precedent that can be transposed to other needs such as recruitment or support for the taking up of positions for key managers, each new version constituting an innovation in itself. This way of introducing new capabilities and enhancing them is specific to this entity. Identifying and sharing the achievements of this experience on a simple and readable map, supplementing it with a definition of key success factors and pitfalls to avoid in an appropriate formalism, makes it possible to effectively assess the opportunity to inspire elsewhere in the organization.

Cellular organizations

As soon as the first potential contributors to IPM are identified, the question of organization comes to mind. Their assignments benefit from being done pragmatically, exclusively on a part-time basis, anticipating a so-called cellular model characterized by its flexibility, the fluidity of the process of creation, disappearance and transfer of teams dedicated to components of the scope of application in according to their constantly reassessed potential. Cellular organizations have been adopted by most multinational innovation leaders, in various versions and under various names, but always sticking to the fundamentals raised. This type of structure releases creativity while streamlining critical processes, including detection, measurement, openness and prioritization of innovation. But not everything is innovation. Care must also be taken to manage the phases after the introduction of a new capability, the day when it has matured and when the competition has structured itself into a real market, when the technological, managerial or relational advance has been transformed in dominance by optimizing the price-quality couple. Cellular organizations are also adapted to these issues. They are historically present among online distribution leaders who have generalized the concept of servicization, among information technology leaders who have placed the configuration management of products and services at the heart of their strategy, and among most companies so-called hyper-growing favoring a dynamic continuous innovation approach. They are now penetrating all sectors via the agile trend.

Anticipating Cellular Organization (Photo by Landon Arnold on Unsplash)

Agility is in fashion because the time horizon of strategists is getting shorter. The more the future is uncertain, the more piloting is done on sight. The risk is to generate fuzzy organizations, where responsibilities are diffused, where tactics prevail over strategy, while all innovative leaders without exception are on the contrary very structured around stable long-term objectives. Since the beginning of the adventure, Tesla’s roadmap has been communicated at 10 or even 15 years, even if inevitable readjustments of the initial copy are regularly recorded. LinkedIn’s growth levels before its takeover by Microsoft were anticipated over the long term thanks to relational network workforce growth models, even if the monetization of this progress was not fully understood in advance. If the strategy evolves in line with the evolution of the assumptions on which it is based, it corresponds to a vision that is more sustainable. Tesla’s bet is that an inescapable trend is at work, increasing the volume of demand and lowering the prices of electric vehicles, at least for 20 years. The pace of this movement is not precisely known at the start, but its assessment is more and more accurate over the years, the experience of this new market being carefully capitalized to build increasingly reliable forecasting models. On the LinkedIn side, the certainty that the need to streamline professional connections is growing has presided over all the major choices, at least in the first decade of its history. The more the network operation statistics were enriched with new data, the more the accuracy of the planning increased. This principle of articulation between vision and strategy is applicable to any idea that generates potential innovations. An innovation cell is easier to mobilize if its members believe in an asserted, shared and justified vision. If, moreover, this vision is confirmed over time thanks to a succession of positive events, support for the project is strengthened.

Well-thought-out agility is therefore not just an organizational principle and a method. It is also the result of a collection of visions (ideas that generate potential innovations) and implementation strategies (the framing of innovation projects). A cell exists from the moment when vision and innovation strategy form a coherent whole, confirmed by experience. If this is not or no longer the case, the cell disappears. It can be recreated to pursue new avenues of resolution, or wait to be called upon again, in this form or another.

Collaborative tool

The contributors to the establishment of an IPM vision and a mapping of maturities already devote part of their time, even a minor one, to training and applying the fundamentals of the approach. In the short term, the idea is to offer them a flexible mode of operation modeled on the model of innovation cells, without prejudging their future number or their speed of deployment: one cell per subset is a sufficient number to this stage. Their members, while being mainly mobilized on their usual tasks in the field, such as operations or projects, gradually acquire skills in terms of IPM that they apply where they are. To achieve this, they must effectively share their know-how through a rapidly operational collaborative environment. At this stage, while the work of collecting information and integrating the fundamental levers of IPM is in its early phase, preference is given to an existing collaborative tool respecting the orientations of the organization in terms of information systems. Later (part 2, month 4 of this program: selecting software), a panorama of solutions specific to IPM will be presented as well as the sets of appropriate selection criteria, in particular in terms of its openness to external innovation ecosystems.

Choosing a collaborative tool (Photo by Marvin Meyer on Unsplash)

But one tool is not everything. The way it is used, how it fits into the organization’s culture and virtuous processes, is at least as structuring as its catalog of features. A market leader in software packages specialized in IPM, such as Qmarkets or craft.io, offers advanced functions, such as measuring the level of attrition between the number of ideas generating potential innovations at a given time and the number of proven innovations successfully introduced hours, days or months later (a so-called “funnel” function). But for this to be useful, prerequisites must be honored, such as the sharing of selection criteria for ideas to be transformed into projects, and therefore to be financed, and a great lucidity with regard to the success factors of these initiatives. The attrition figure alone does not allow progress from this point of view: it must be combined with simple, reliable and well-chosen qualitative analysis elements. Another spectacular function of this type of tool is a graphical representation of the relative importance of the different trends at work in the ecosystem under consideration (examples among others: servitization, deep learning, dronization, green energy, agility, blockchain, cyberquantum, participatory communication). The density of innovation initiatives, the intensity of the investment granted or the average success rate recorded can be analyzed according to this trend axis in order to make concrete and structuring decisions, in particular that of changing the distribution profile of the initiatives in the innovation portfolio. It is a question of favoring the trends in which the organization believes, of abandoning those which in its view will not confirm or no longer confirm the hopes they gave rise to, and of piloting on a case-by-case basis the initiatives which do not come under either nor others. To make these reasonings and make these high-impact decisions, a simple graph is not enough. It is still necessary to qualify in a relevant way the reasons for which a trend turns out to be promising or not.

As soon as a tool is identified to support a given use, the question of its interoperability with the rest of the information system arises. However, at this stage, this need for interoperability is rather limited. Indeed, one of the classic pitfalls consists in initializing such a tool via a migration or the reuse of an existing space, already used to manage a portfolio of projects. It is rather desirable to entrust the constitution of the first portfolio of innovation initiatives to the pioneers (see next paragraph) and not to programs. Thus the amalgam is avoided between innovation projects, aimed at acquiring a unique capability on the market or in their ecosystem, and just projects. The quality of the content of the selected collaborative tool is by far preferable to its quantity or volume. It is with patience that a culture of virtuous innovation is built. Of course, justified exceptions exist. In particular, when a maturity diagnosis concludes that one of the subsets has already deployed a large-scale IPM process and has reached or exceeded the “opening” zone or the “prioritization” zone, the collaborative space is already operational and rich in usable data.

Network of pioneers

The members of the first innovation cells are intended to circulate information. Within a network of pioneers, they are called upon to identify opportunities for creating value, to share them and, if necessary, to make them happen with the support of other members, in particular that of decision-makers. This means that decision-makers are part of the innovation cells, in a proportion to be defined. Typically, at least 20% of the workforce must be able to make 80% of the focus, pivot or arbitration decisions, in consultation with the other managers involved. This is an important feature of cell-type organizations, where about one in 5-7 people has the power to move most issues forward by choosing one of the options offered to them by their cell co-members. After having piloted the establishment of an IPM vision and having declined it by homogeneous subset of the organization, the first contributors begin an initial assessment of the potential for value creation linked to the deployment of this approach on their own scope of work, and gradually constitute a first corpus of shareable data. The permanent confrontation with the field makes it possible to continuously refine these results. These actions respect a principle of simplicity and regularity, in accordance with an agile-type approach. The participants of the first workshop are invited to lead meetings with experts capable of answering outstanding questions relating to past innovation projects, in particular the factors of success and failure of these initiatives. Thus they will arrive at the second workshop equipped with new arguments to build their innovation strategy.

Initiating a network of pioneers (Photo by krakenimages on Unsplash)

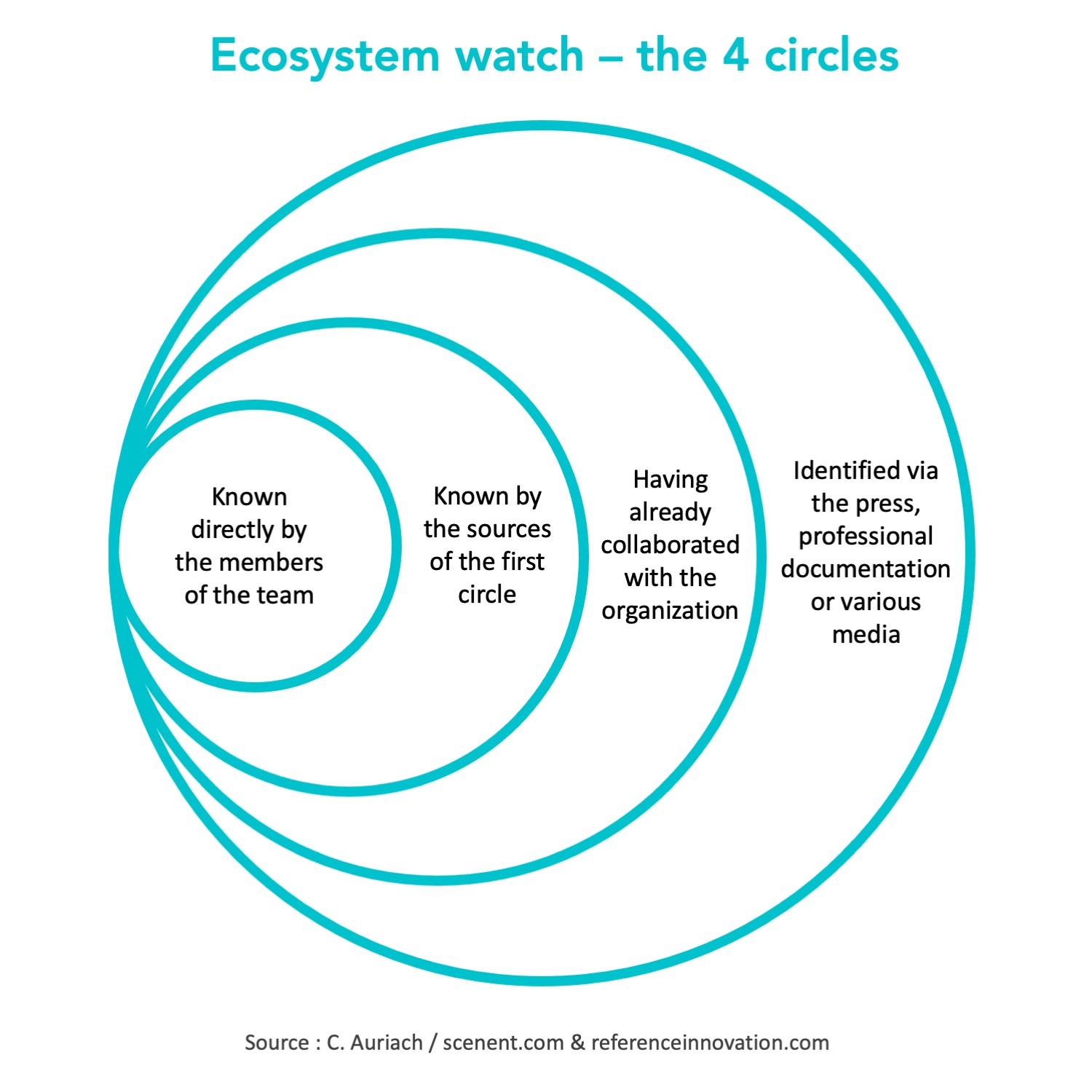

Knowing what is happening inside and outside the organization, understanding the innovative dynamics at work and having the ability to connect the dots is an important key to performance. Many companies are opening open innovation manager positions, reporting to the Chief Innovation Officer. These professionals scan the market and supply the watch databases with potential assets, aligned with the innovation strategy. The same process can be implemented internally. Also, the post-mortems of internal innovation projects must be conducted with the right level of efficiency to avoid the pitfalls already encountered, reproduce the methods that work and exploit the potential of dormant assets. It is at this price that the number of projects reinventing what has already been invented is reduced and that energy is concentrated on real innovations or on conscientious imitations. The potential for gain linked to this dynamic is increasingly important, information relating to reusable components becoming more and more accessible, both in product and service oriented activities. It remains to discern in this mass of information what is useful and what is not. The best master the relationship between their discernment effort and its impact on the value provided by the growth of their effective reuse rate. In this context, artificial intelligence plays an increasingly important role and the formation of the network of pioneers must ultimately take this into account. If there is a trend affecting the IPM process itself, whatever the nature of the organization concerned, it is the development of artificial intelligence in the service of the maintenance of a catalog of assets at potential. This subject is at the heart of particularly promising innovation management research programs. As part of this training curriculum, it will be covered in more depth in the sessions part 2, month 8: promising trends and part 4, month 9: AI lever. Constantly revisited in the light of changes in the ecosystem, this content will be updated until then to take into account the progress observed in the field of IPM, because this discipline is in the grip of upheavals and new avenues for resolution are emerging every week. In the meantime, priority is given to the organization and reliability of the data on which these analysis engines will be based, through the constitution and maintenance of a portfolio of qualified initiatives. It is to this task that the network of pioneers will tackle, before possibly considering advanced solutions that can go as far as the creation of digital twins of IPM processes.

Pilot portfolio

There are more and more agile initiatives within a variety of organizations. Also the coexistence of innovation cells, Scrum or Sprint teams, Kaizen or Lean cells, must be well understood. They all share the same principle of flexibility of creation, decommissioning and transfer, which avoids piling up organizational strata that do not come apart when the need that presided over their constitution has disappeared. However, they each have different objectives. The long-term objective assigned to the innovation units is to help steer a portfolio of innovation projects from the perspective of their performance across the entire organization, in a way giving visibility to decision-makers or even shareholders on the actionable levers to improve, in the other way visibility for each employee, by capillarity, on the success factors of these improvements.

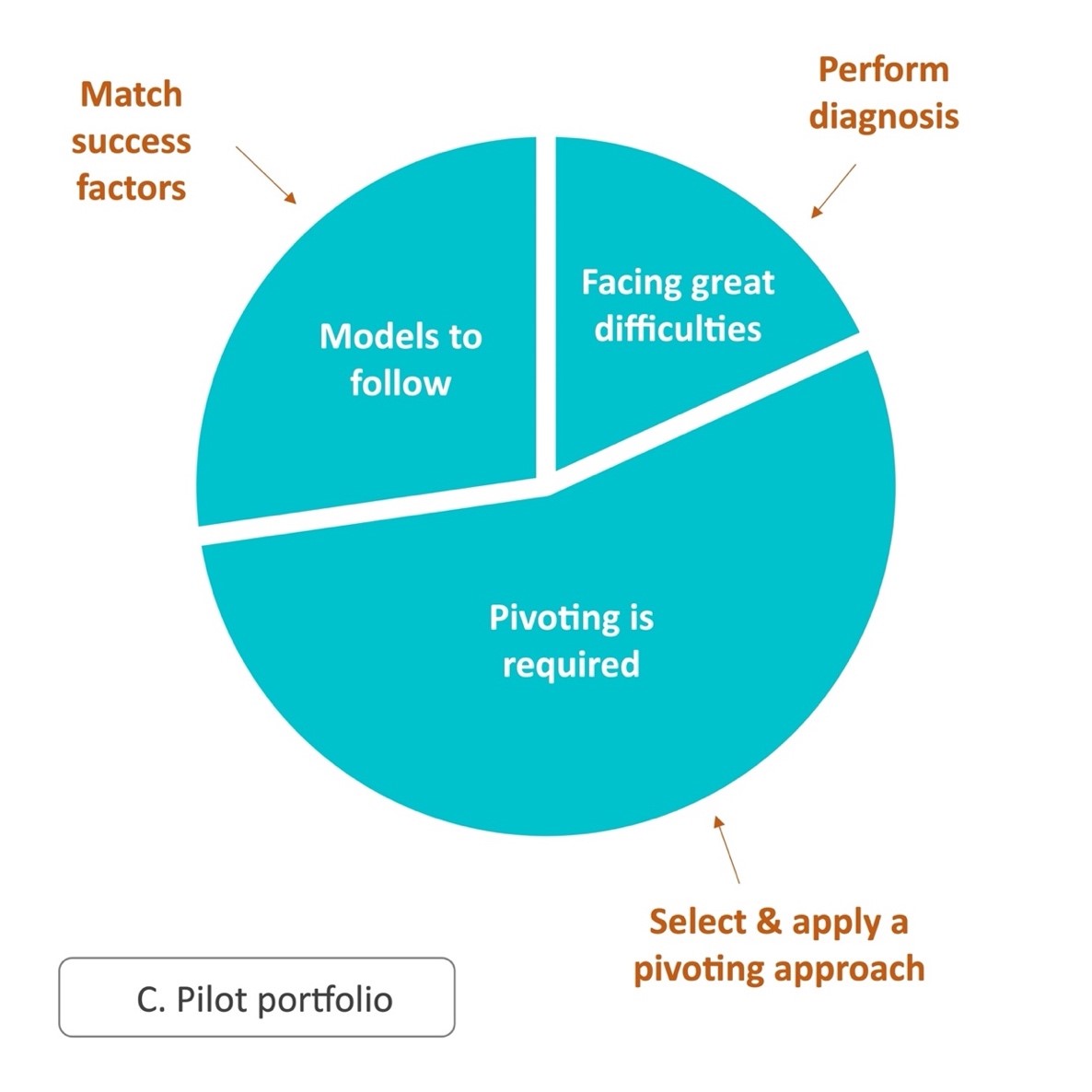

In the immediate term, this positioning is reflected in the constitution of an initial portfolio of pilot projects, based on the initial evaluations carried out by the members of the innovation cells in their respective fields. During the workshop and the informal meetings that follow, past, present and future innovation projects are discussed. Some of them meet the right criteria for forming an initial portfolio of innovation projects, either because they represent models to follow, or because they are encountering significant difficulties, or because the need for pivoting emerges (see figure C. hereafter).

Model projects are generally advanced, benefiting from sufficient hindsight for confidence in a happy ending to be strong. They benefit from being studied to detect common factors of success, to be confronted with the IPM vision in order to nourish and adapt it. Projects in great difficulty are generally subject to specific support measures and should not be disturbed more than they already are. However, the confrontation with the IPM vision can be the trigger for the exploration of new avenues of resolution, which should not be neglected. Projects for which the need for a change in operating or economic model has been identified are subject to appropriate monitoring. There are methods of accelerated pivoting that are insufficiently practiced today, especially in the service sector, such as TRIZ for example. However, they are mastered and have proven themselves in industry, particularly in high-tech electronics, and their transposition in the service sector or in the transverse functions of companies is one of the major challenges of the moment. Even if the members of the innovation cells do not necessarily have the skills to carry out these initiatives at this stage, they prepare for them by integrating these projects into the initial portfolio.

One of the key skills to acquire is the ability to assess whether to pivot or not. TRIZ, already mentioned, is a method for identifying, triggering and framing possible solutions adapted to a given problem. It has the advantage of rotating a concept upstream as many times as necessary before spending the first dollar on its actual prototyping. However, among the causes of inefficiency in innovation portfolios, late pivoting is in a good place. This is due to a very human and quite understandable reflex which consists in digging a path to the end before resolving to abandon it if it does not yield tangible results. However, if regular hindsights are organized in order to seriously ask the question of continuing on a path or changing it, supported by the right process, the right tools and the right methods, unnecessary efforts become avoidable. If a fortiori these hindsights are taken in anticipation even before the start of an innovation project, thanks to a reasoned anticipation of the most probable events capable of affecting its progress, the gain is all the greater. This is made possible by the progress made in simulation, without having to resort to IT capabilities, but rather by leading co-creation workshops that give pride of place to role-playing games.

What is TRIZ in a nutshell? This is a detailed guide for evaluating a problem using known and reusable innovation patterns. This method is further described in course manual 2: Scope of application – scientific and technological culture, as well as in sessions part 1, month 7: methodology sharing and part 2, month 7: facilitating innovation. It makes it possible to pivot upstream because it integrates a large number of concrete questions already asked in previous innovation projects (model projects) which have successfully brought out new avenues for resolution. It is not a question of tackling ready-made solutions on a context, but of following a proven decision tree. It is essential to maintain great flexibility at each stage of the method in order to free the creativity of the participants, according to the well-known principle of serendipity: TRIZ suggests, the participants imagine; they bounce off those suggestions and forge new paths, iterate, go back, go forward, and start again.

Initial dashboard

Assessing the performance of an innovation project supposes on the one hand to distinguish what an innovation project is and why it is useful to know it, on the other hand to have a simple, proven reporting grid that is effective, deployable in the field. Participants will emerge from the first workshop understanding the essential characteristics of an innovation project, not only in terms of what defines it, but also and above all in terms of its potential for creating distinctive value.

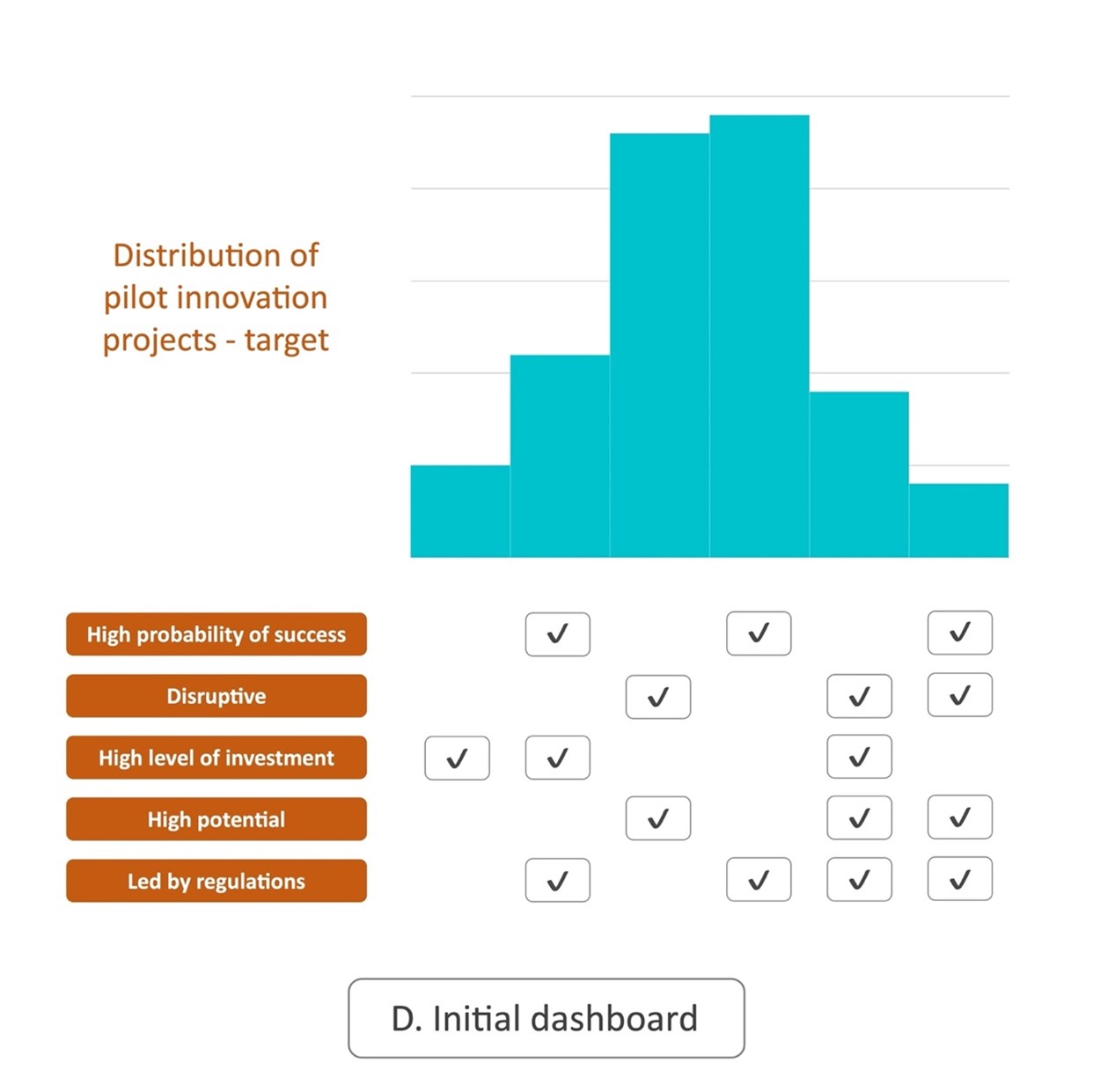

Whatever the nature of the organization considered, when the number of innovation projects is large enough, they constitute a collection of assets that must be managed. Just as an asset manager uses portfolio management techniques to optimize his/her risk/return ratio, a decision-maker makes choices by stimulating, initiating, stopping or adapting the level of investment in his/her innovation projects. Before growing the portfolio, it is necessary to anticipate the desired distribution according to the key axes which are the probability of success, the ambition of the disruptive or continuous type, the level of investment, the potential and regulatory obligations. Thus it will be possible to align the process of validating the entry of a project into the portfolio taking into account the right criteria, both bottom-up (need for IPM support from the field) and top-down (need for balancing the portfolio in terms of the risk /return ratio). This approach has points in common with that of an investment fund specializing in innovation, particularly in terms of its top-down dimension. It differs in particular insofar as synergies between innovation projects, and between innovation projects and other projects are sought in order to establish or develop a coherent corporate culture that generates sustainable growth. It also incorporates considerations unrelated to innovation as such, the organization not only having the vocation to innovate and enhance innovation, but also to enhance its non-innovative, competitive assets with a strong economic, environmental, and societal impact. The logic of managing the portfolio of innovation projects is also virtuous in that it makes it possible to better manage make or buy type choices, by ultimately comparing internal or outsourced solutions on perimeters deemed to be non-strategic. In the meantime, an initial dashboard is proposed, representing both the positioning of the first pilot projects in the portfolio, and the positioning expected in the future. We can thus anticipate that there will be fewer projects presenting at the same time a high probability of success, a disruptive aspect, a low level of investment, a high potential and a regulatory obligation (right column in Figure D. below), than continuous innovation projects requiring substantial investment with limited potential (third column from the right in the same figure).

The first time a portfolio of innovation initiatives is characterized in this way, the initial distribution may turn out to be surprising or even highly counter-intuitive. For example, if in a given field the contributors to innovation thought that the probability of success was low, it may turn out to be much higher in reality because non-innovative initiatives have been excluded from the analysis base: the denominator of this success rate decreases, so its value increases. Conversely, the level of cumulative investment in innovation, if it is considered low a priori, may turn out to be higher after analysis, in the case where innovation projects are financed by non-dedicated budgetary envelopes, therefore hard to identify, or on the margins of other projects or initiatives.

The Gaussian curve illustrated by the figure above seems to be a fatality. Experience shows that it is unreasonable to think that it is possible to drag the rightmost column (a priori the most enviable situation) towards the center, therefore towards the highest number of occurrences. On the other hand, each situation corresponds to an appropriate response. Even in the a priori most favorable case, for example when a disruptive approach is encouraged by the regulatory environment and trends, as may be the case for central bank digital currencies, the step is so high that it is good to limit the number of initiatives of this type: otherwise, the major risk is not to master their simultaneous scale-up phases. This leads us to systematically consider the couple innovative initiative / scaling up project. Beyond proof of the validity of an innovative concept, process, product or service, obtained at the end of the innovation project, the deployment or industrialization phase may turn out to be more or less resource-consuming and more or less risky. As by definition we do not know in advance the nature of an innovation, the a priori assessment of this level of resource consumption and risk is most often hazardous. To achieve this under the right conditions, the innovation project would have to be framed by an excess of hypotheses, thereby killing its innovative nature and curbing the creativity of the actors.

By accepting the inevitability of the Gauss curve of the innovation portfolio, virtuous effects emerge. For example, constraining the leftmost column to stay there is highly desirable. It reports on initiatives with a single characteristic (a high level of resource consumption), negative, without any compensation in terms of success rate, disruption, potential for value creation or stimulation by a regulatory trend. Multiplying initiatives of this kind would be at best a waste of energy, at worst endangering the economic model of the organization. However, if there is no clear measurement of the phenomenon, it is possible to miss it, or at least to detect it late. Another example is provided by a center column, reporting initiatives imposed by the regulator with a high probability of success. Given the dynamism of regulators in most sectors, trying to keep up with the rapid pace of introduction of innovations of an organizational, societal, environmental and technological nature, it is not possible to see a low success rate on this segment.

IPM Strategy

For each type of project, the success factors may vary. If all have in common a positive sensitivity to focusing and pivoting flexibility, other factors must be adapted according to the choices made. For example, the functional outline for a spin-off or IPO operation will be more suited to a disruptive innovation than to a continuous innovation. Similarly, an open innovation approach is generally more important for high-potential projects than for others. These considerations make it possible to break down the IPM vision into strategic axes for each subset of the organization, based on the assessment of its maturity (see above, figure B). They are federated into an IPM strategy, the purpose of which is to create the conditions for raising the value generated by innovation initiatives within an organization. The transformation of the IPM vision into an IPM strategy is facilitated by the availability of an initial portfolio of concrete projects that have been the subject of an initial assessment: the axes of the strategy being developed can be tested on this limited scope for purposes of reliability and pedagogy.

IPM strategy (Photo by Matt Ridley on Unsplash)

The questions most frequently addressed by an initial IPM strategy are, on the one hand, the level of connection of innovative initiatives to the expectations of their target ecosystem, and, on the other hand, the level of awareness and training of staff on the importance of managing the performance of its innovation portfolio while stimulating the creativity of all the players involved. Increasing the maturity of an organization according to these two axes is a challenge shared by organizations where innovation is opportunistic, the goodwill and spontaneous creativity of the actors being at the origin of most of the initiatives.

While it is important to maintain, and even encourage and develop the autonomous initiatives of contributors to innovation, verifying their alignment with the expectations of the targeted beneficiaries is a major performance lever. If the collection and updating of these expectations are neither organized nor optimized, they have little chance of influencing the innovation process on the desired scale. A key advantage of starting with this project is obtaining rapid results that can be promoted through appropriate communication, and generate a virtuous ripple effect. Indeed, the integration of witnesses of an ecosystem in working groups, co-creating avenues for resolution with the personnel of the organization, causes a positive shock. In the frequent case of doubt relating to the relevance of an innovative initiative, the uncontested arbiter is the beneficiary or his or her representative. If two internal departments clash over the design of a joint offering, the justice of the peace is the end customer. In addition, these witnesses with whom a closeness is established become the promoteurs of the organization around them and can express themselves on a number of subjects, in particular the comparison with the competing offerings to which they are exposed.

At the same time, starting to adopt an innovation management posture leads to redirecting initiatives that are out of step with the expectations of the ecosystem, or to abandon them if no pivoting is possible. An IPM approach necessarily brings together left brain and right brain, analysis and creativity, reasoning and spontaneity at each stage, including the first.

Defining your IPM strategy (Photo by kvalifik on Unsplash)

Storytelling

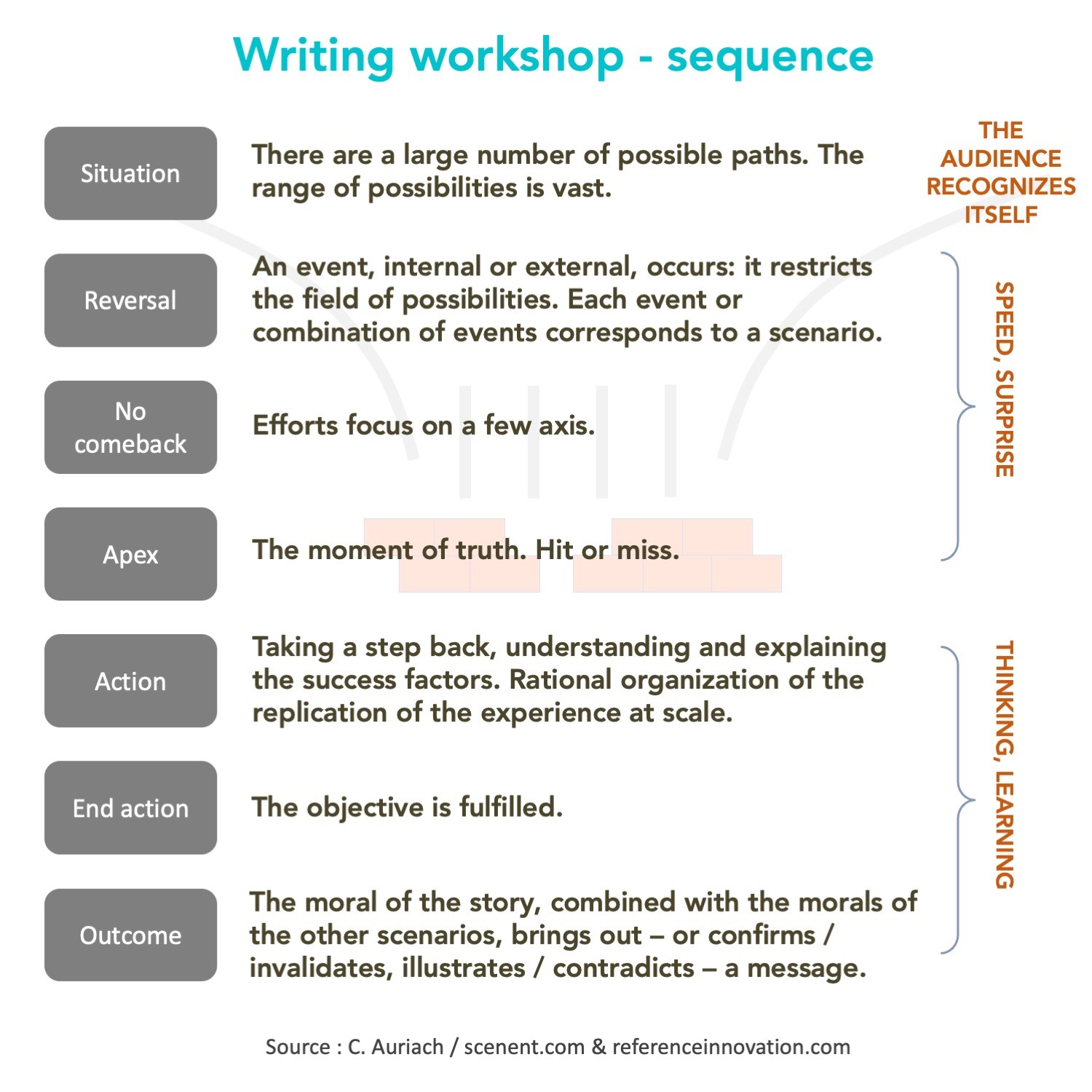

Rather than communicating directly on the IPM strategy, it is preferable at this stage to focus on its concrete illustration through examples. Successful innovative companies convey legends within their organization, positive and negative, contributing to the creation and maintenance of a specific culture, recognizable, symbolized and confirming a strong identity over time. A simple way to drive such momentum is to collect and promote stories of innovation on a variety of channels, oral, written, audiovisual, virtual and physical. The key asset of the initiative is a body of script-like texts. This Storytelling approach is an effective way to mobilize the members of the innovation cells and to invite them themselves to collect new stories and relay them around them, wherever they are. A simple and proven approach, inspired by the methods taught in screenwriting schools, is proposed. At this stage, it is applicable without extensive training. It will be deepened later (in particular part 3, month 3 of this program: training program).

When a recurring problem is particularly penalizing, there is always a first leader, then a second, and so on, to ask to be told the story of the most significant incidents, to understand what those who suffer it are going through and try to contribute to its resolution. Conversely, when an avalanche of success catches the attention of the same leaders, they want to be told the stories that got the organization to where it is today, because they believe they are then better able to replicate those successes elsewhere. When a serial entrepreneur plans to embark on a new adventure, in a sector that he or she does not yet know, she or he is “told the story” of this market, of this ecosystem. When it comes to promoting a talented employee, the decision-maker is told the story, the “curriculum” of the person concerned, and will dwell on the feats of arms, and even on the anecdotes translating and conveying the personality of the candidate. Telling stories is the best way to “make people understand what is happening”. And “understanding what is happening” is the condition of trust and adherence to any project. For example, let’s go back to the first case mentioned above, that of the penalizing recurring problem. The resolution process can be told as follows:

• first, the teams in charge of the subject identify the problem;

• they struggle with the symptoms, which arise when you least expect them;

• others look into the matter, moving from symptoms to causes;

• causes are eliminated through action plans;

• symptoms remain, new symptoms appear;

• the previous cycle (search for causes and action plan) is repeated;

• reports are shared with the hierarchy;

• a debate is taking place between those who think that the real causes have not been identified, and those who think that they are but that no solution has been found to eliminate them;

• another debate is taking place between supporters of so-called “classic” solutions (imitation of what has already worked elsewhere) and supporters of innovative, disruptive solutions;

• the outcome is uncertain, the emotion is at its peak.

Whether the conclusion is positive or negative, the audience of the story must identify with the protagonists and feel emotion. The highlights are reported by the witnesses of the experience and relayed by others. For example, the unexpected intrusion of actors outside the context can bring a fresh eye and pivot the avenues of resolution envisaged by the think tank in charge of the subject, or the pressure felt by the manager struggling with his or her problem can be rendered thanks to evocative verbatims. The passion and originality of the storytellers or writers do the rest.

Collaborative ecosystems

Participants are invited to revisit these stories of innovation by considering alternative scenarios. They are guided by the IPM strategy and by an introduction to the fundamentals of open innovation: how the impact of the innovation in question could have been multiplied by having more systematic recourse to external collaborations, including and especially upstream ? How could this contribution have been organized? This exercise makes it possible to offer an introduction to the collaborative ecosystems, their pitfalls as well as their virtues. Since open dynamics often take a long time to set up, it is good to make an effort to raise awareness on the subject as soon as possible. Indeed, many obstacles must be overcome. Among them, the fear of seeing the dilution of know-how which may have been subject to a high level of protection until now. It is therefore necessary to take the time to explain and convince with the help of business cases balancing the expected gain and the level of risk specific to each asset deemed sensitive (see part 3, month 8 of this program: open innovation). In the short term, only the fundamentals of the approach are shared (see figure E. below), emphasizing the importance of setting up sustainable and growing panels of customers and prospects, which can be mobilized regularly to test new offerings. In practice, there are often existing initiatives in this vein. At first, it is a question of identifying or revealing them, then of taking a close interest in them in order to understand the concrete ins and outs.

How do you find enough time to interact with these witnesses? We can return the question: where do these witnesses find the time to interact with the representatives of the subset considered? And above all, why do they find this time? What are their motivations and what makes them become loyal contributors, most often volunteers? In practice, by thinking about the future of their supplier, their partner or their customer, they are thinking about their own future. They benefit from this joint reflection like all the other stakeholders, insofar as they form an ecosystem. If these sessions are led by third parties, they benefit from their methodological contribution, their potentially offbeat perspective and their experience of other ecosystems. Concretely, imagine a session where a large audit and consulting firm invites representatives of large listed companies to reflect on the state of the art of management reporting formats in a sustainable development context. The firm will come out of the experience having received the expectations of its clients and prospects, while these companies will take with them ideas that they would not have had on their own; they may even implement them immediately, without waiting for the firm to include them in its catalogue of offerings. For this dynamic to work in the long term, the interests of the parties must be balanced. Facilitators of such sessions should ensure this.

Initial communication plan

Equipped with these initial results, IPM vision, scope of application, mapping of maturities, mission to mobilize a network of pioneers in cellular mode, selection of an existing collaborative tool, initiation of a first pilot portfolio and a first dashboard, IPM strategy, a bouquet of innovation stories and awareness of the potential of collaborative ecosystems, participants are ready to complete their copy by soliciting knowledgeable people around them. This first workshop being intended for leaders, managers, project managers and project innovation directors deployed in organizations with 1000 to 100,000 employees, and opening a sequence of 48 stages spread over 4 years during which the IPM process will first be tested in pilot mode, then customized, deployed and finally optimized, new contributors will join the initiative every month. They will have to be trained, made aware, informed and mobilized thanks to a duly updated communication plan. The first version of this communication plan focuses on a selection of stories collected during and after the first workshop.