Emotional Competence – Workshop 1 (24hr Emotions)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Emotional Competence is provided by Ms. Goj Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

To be advised.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

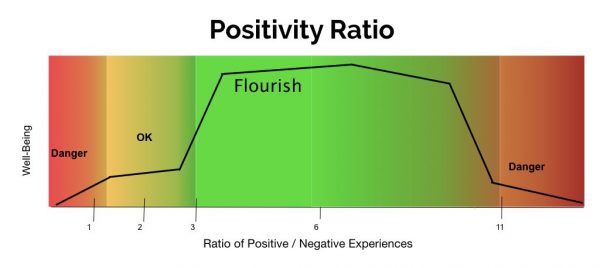

Coaching session using the Positivity Ratio.Take two minutes to complete the Positivity Self Test now. Your score provides a snapshot of how your emotions of the past day combine to create your positivity ratio.

Objectives

01. Positivity Ratio: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Emotion Importance: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Workplace Emotions: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Positive Emotions: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Negative Emotions: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Emotional Triggers: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Emotional Control: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Group Emotional Intelligence: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Emotional Culture: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Increasing Positivity: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Team Performance: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Positivity Ratio: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Emotion Importance: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Workplace Emotions: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Positive Emotions: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Negative Emotions: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Emotional Triggers: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Emotional Control: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Group Emotional Intelligence: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Emotional Culture: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Increasing Positivity: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Team Performance: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Positivity Ratio.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Emotion Importance.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Workplace Emotions.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Positive Emotions.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Negative Emotions.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Emotional Triggers.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Emotional Control.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Group Emotional Intelligence.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Emotional Culture.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Increasing Positivity.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Resilience.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Team Performance.

Introduction

Control your energy instead of your time.

Steve Wanner, a partner at Ernst & Small who is 37 years old, is well-liked and married with four young children. He was working 12- to 14-hour days when we first met him, always felt weary, and struggled to completely engage with his family in the evenings, which made him feel guilty and unsatisfied. He had trouble sleeping, didn’t find time to work out, and rarely ate healthy meals; instead, he would grab a snack while he was on the go or sitting at his desk.

Wanner’s situation is not unusual. The majority of us increase our work hours in response to increasing demands at work, but this will eventually have an adverse effect on our physical, mental, and emotional health. As a result, there is a decline in employee engagement, an increase in distraction, high rates of turnover, and skyrocketing medical expenses. Over the past five years, the Energy Project has provided consulting and coaching to numerous large enterprises, working with thousands of executives and managers. These CEOs tell us they’re working harder than ever to keep up with things and that they increasingly feel like they are reaching their breaking point with startling consistency.

The fact that time is a limited resource is the main issue with working longer hours. Another matter entirely is energy. Energy, which in physics is defined as the ability to operate, originates in humans from four basic sources: the body, emotions, mind, and spirit. By establishing specialised rituals—behaviors that are deliberately repeated and meticulously organised, with the objective of making them unconscious and automatic as rapidly as possible—energy can be methodically extended and routinely renewed in each.

The fact that time is a limited resource is the main issue with working longer hours. Another matter entirely is energy.

Organizations must change their focus from getting more out of people to investing more in them in order to motivate and enable them to bring more of themselves to work every day. This will effectively reenergize their workforces. Individuals need to take responsibility for changing their energy-draining activities regardless of the situation they find themselves in in order to recharge.

Wanner’s life was changed by the routines and habits he developed to better manage his energies. He gave up drinking because it was keeping him up at night and set an earlier bedtime. Because of this, he awoke feeling more refreshed and inspired to work out, which he now does virtually every morning. He shed 15 pounds in less than two months. He now has breakfast with his family after working out. Wanner continues to put in hard hours at work, but he often rejuvenates himself in the process. He normally goes outside for a morning and an afternoon walk, and he gets up from his desk for lunch. He is more at ease and able to connect with his wife and kids when he gets home in the evening.

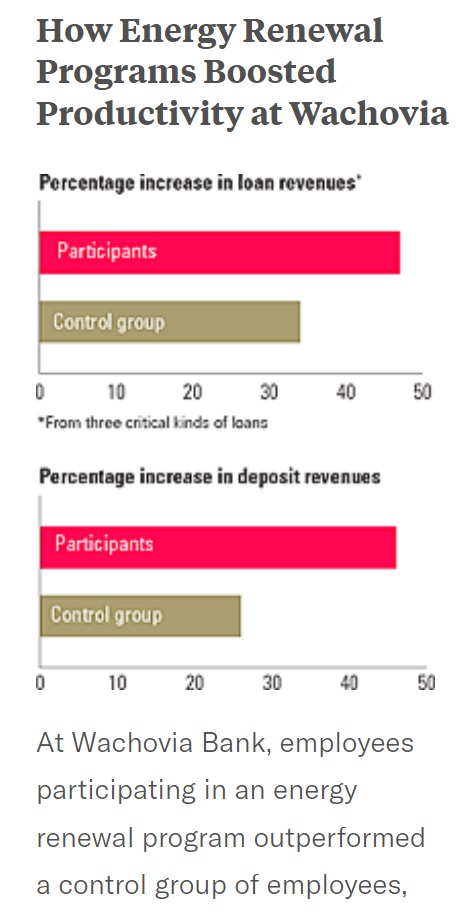

Simple rituals like this can be established to produce impressive benefits throughout businesses. We put a group of workers through a trial energy management programme at Wachovia Bank and then compared their output to a control group’s. In terms of a number of financial criteria, including the amount of loans they produced, the participants beat the controls. Additionally, they reported significant improvements in their interactions with customers, their commitment to their jobs, and their level of pleasure.

Wachovia’s Linking Capacity and Performance

The majority of large firms make investments in the knowledge, competence, and skills of their workforce. Few contribute to the development and maintenance of their capacity—their energy—which is frequently taken for granted. In reality, increased capacity enables more to be accomplished in less time with better involvement and sustainability.

How Energy Renewal Programs at Wachovia Increased Productivity

Employees at Wachovia Bank who took part in an energy renewal initiative performed better than a control group,…

Participants were also questioned about how the programme affected them personally. It improved their relationships with clients and customers, according to 68% of respondents. Seventy-one percent of respondents claimed that it significantly or noticeably improved their performance and productivity. These results supported a wealth of anecdotal data we’d gathered about the success of this strategy among executives at other big businesses like Ernst & Young, Sony, Deutsche Bank, Nokia, ING Direct, Ford, and MasterCard.

The Emotions: Energy Level

Regardless of the stress they are under from the outside world, people can increase the quality of their energy when they are able to better manage their emotions. To do this, people must first become more conscious of their emotions and the effects those emotions have on their productivity during the course of the workday. Most people are aware that their performance tends to be at its highest when they are feeling upbeat. They find it shocking that when they are feeling any other way, they are unable to lead or perform successfully.

.

We are unfortunately not physiologically able to sustain intensely joyful feelings for extended periods of time without intermittent recovery. When faced with constant demands and unforeseen difficulties, people frequently experience negative emotions (the fight-or-flight response) several times during the day. They start to feel nervous and insecure, perhaps angry and impatient. Such mental states sap people’s energy and lead to conflict in their interpersonal connections. Clear, logical, and reflective thought are also all but impossible when experiencing fight-or-flight feelings. Executives have a higher ability to control their reactions when they learn to identify the circumstances that make them feel bad.

Expressing gratitude to others, a ritual that seems to be as helpful to the giver as it is to the receiver, is a strong one that fosters happy emotions. It can be delivered orally, in writing, via email, phone call, or in-person interaction, and the more exact and thorough, the more powerful the message. Like other rituals, the likelihood of success is greatly increased by designating a specific time to carry it out. Ben Jenkins, vice chairman and president of the General Bank at Wachovia in Charlotte, North Carolina, included his ritual of appreciation into the allotted period for mentoring. He started scheduled frequent lunches or dinners with his employees. Previously, he had only met with his direct reports to offer them annual performance reviews or to receive monthly updates on their financial success. He now prioritises praising their achievements and conversing with them about their lives and objectives during meals rather than their immediate job obligations.

Finally, by learning to alter the stories they tell themselves about the events in their lives, people can learn to nurture positive feelings. Conflicted individuals frequently play the victim, attributing their issues to other people or outside forces. Understanding how the facts of a situation differ from how we interpret those facts can be powerful in and of itself. Many of the individuals we work with have found it to be a revelation that they have a choice in how they interpret an event and that their story has a significant impact on the feelings they experience. Without downplaying or rejecting the realities, we instruct students to provide the most upbeat and personally empowered narrative they can in any given circumstance.

By learning to alter the narratives they tell themselves about the events in their lives, people can learn to cultivate positive energy. We instruct them to tell the most upbeat tales we can.

The best method to change a tale is to look at it from one of three new perspectives, all of which are different from the victim’s point of view. For instance, while using the reverse lens, individuals ask themselves, “What would the other person in this conflict say and in what ways might it be true?” They question, “How will I most likely evaluate this issue in six months?” using the long lens. They question themselves, “Regardless of how this issue turns out, how can I develop and learn from it?” using a broad lens. Each of these perspectives can assist individuals in consciously cultivating more joyful emotions.

When Sony experienced many battery recalls in 2006, Nicolas Babin, head of corporate communications for Sony Europe, served as the lead person for calls from reporters. Over time, he grew more and more worn out and discouraged by his duties. He started figuring out methods to tell himself a more empowering and positive story about his role after completing the lens exercises. He says, “I realised that this was an opportunity for me to build stronger relationships with journalists by being accessible to them and to increase Sony’s credibility by being straightforward and honest.”

The Mind: Energy Concentration

Given all the responsibilities that executives must juggle, multitasking is often seen as necessary, but it actually reduces productivity. Distractions cost money. Switching time is the phenomena whereby the amount of time required to complete the primary activity rises by as much as 25% when attention is briefly diverted from one work to another, such as pausing to answer an email or accept a call. It’s much more effective to give your complete attention for 90 to 120 minutes at a time, break truly, and then give your full attention to the following task. These work sessions are referred to as “ultradian sprints.”

People might develop rituals to lessen the many disruptions that technology has introduced into their life once they become aware of how difficult it is for them to focus. We begin with a practise that makes students confront the effects of daily distractions. People remark that when they try to finish a difficult work but are frequently interrupted, the experience feels a lot like ordinary life.

Focusing systematically on tasks that have the most long-term leverage is an additional strategy for mobilising mental energy. If more difficult work isn’t specifically scheduled into their calendar, individuals frequently put it off or rush through it. The CEOs with whom we work have probably found that choosing the biggest issue for the following day each evening and making it their top priority when they wake up is the most effective focus ritual. As many people do, Jean Luc Duquesne, a vice president for Sony Europe in Paris, used to respond to his e-mail as soon as he arrived at work. He now makes an effort to focus on the most crucial subject for the first hour of each day. At 10 in the morning, he discovers that he frequently feels as though his day has already been productive.

The Human Spirit: Meaning and Purposeful Energy

When people’s daily job and activities are in line with the things they value most and that give them a feeling of meaning and purpose, they are able to access the power of the human spirit. They usually feel more upbeat, have better concentration, and show more endurance when the work they’re doing matters to them. Unfortunately, corporate life’s high expectations and quick speed allow little time for thought on these matters, and many individuals aren’t even aware that meaning and purpose can be sources of energy. Indeed, it is likely to have little effect if we attempt to start our programme by emphasising the human spirit. Participants don’t fully understand how attending to their own deeper needs has a significant impact on their performance and job satisfaction at work until after they have experienced the usefulness of the rituals they build in the other dimensions.

Jonathan Anspacher, a partner at E&Y, found it exhilarating and instructive to simply have the chance to ask himself a series of questions about what truly meant to him. He advised us to ask ourselves, “What do you want to be remembered for?” and to be a little self-reflective. “You don’t want to be known as the crazy partner who put in such long hours and caused his team to suffer. Can you come to my band’s show when my kids phone and ask? I want to confirm that I’ll attend and that I’ll sit in the first row. I don’t want to be the dad who enters the room, sits in the back, checks his Blackberry, then gets up to answer the phone.

The three categories of doing what they do best and enjoy most at work, consciously allocating time and energy to the areas of their lives they deem most important—work, family, health, and service to others, and living their core values in their daily behaviors—are necessary for people to access the energy of the human spirit.

It’s crucial to understand that your best qualities and your favourite activities aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive while trying to figure out who you are and what you enjoy doing most. Even when you excel at something and receive tonnes of compliments on it, you might not actually enjoy it. On the other hand, you can love doing something but not have a talent for it, in which case putting up the effort necessary to succeed is not worthwhile.

We invite programme participants to think back on at least two professional experiences from the previous several months during which they felt effective, effortlessly absorbed, inspired, and fulfilled. This will help them identify their areas of strength. Then, we ask students to analyse those events to determine precisely what motivated them in such a positive way and what particular skills they were using. Is being in command or engaging in creative work more energising, for example, if leading strategy seems like a sweet spot? Or is it practising a skill that naturally comes to you and makes you feel good? Finally, we ask participants to create a ritual that will motivate them to engage in more of precisely that kind of work activity.

There is frequently a comparable gap between what individuals say is important and what they actually do in the second category, investing time and attention to what is important to you. Rituals may be able to bridge this gap. Spending time with his family was the thing that meant most to Jean Luc Duquesne, the vice president of Sony Europe, yet it frequently got squeezed out of his day when he gave it any serious thought. So that he could concentrate on his family, he established a ritual in which he switches off for at least three hours every evening when he gets home. He admitted to, “I’m still not an expert on PlayStation,” he said, “but according to my youngest son, I’m learning and I’m a good student.” When Steve Wanner commuted home, he used to talk on his cell phone all the way to his front door. Now, he has a designated location 20 minutes from his home where he finishes calls and puts his phone away. In order to be less focused on work and more available to his wife and kids when he gets home, he relaxes for the remainder of his drive.

Many people find it difficult to live out their primary principles in their daily activity, which falls under the third category. Most people move through life at such a rapid speed that they rarely take time to reflect on their values and goals. As a result, they allowed outside pressures to direct their behaviour.

We don’t advise people to state their values openly because the outcomes are typically too predictable. As an alternative, we try to elicit them, in part by using unintentionally illuminating questions like, “What are the attributes that you find most repulsive when you see them in others?” People accidentally reveal what they stand for by expressing what they can’t tolerate. For instance, if you find stinginess to be particularly offensive, generosity is certainly one of your core values. Consideration is probably a high value for you if you are particularly offended by rudeness in others. Similar to the other categories, creating rituals can aid in bridging the gap between your current behaviour and the values you aspire to. The practise can be to terminate meetings you run five minutes earlier than usual and purposefully arrive five minutes early for the meeting that comes next if you find that thoughtfulness is a core value but you are consistently late for meetings.

People can make significant progress toward reaching a higher feeling of alignment, pleasure, and well-being in their life both on and off the job by addressing these three categories. These emotions themselves are a source of good energy, and they encourage participants to stick with rituals in other energy dimensions as well.

Only to the extent that firms encourage their employees to adopt new behaviours will this new method of working become widespread. We have discovered, sometimes painfully, that not all business leaders and organisations are willing to accept the idea that employee personal rejuvenation would result in higher and more long-lasting performance. Renewal initiatives require strong backing and dedication from senior management, starting with the primary decision maker.

Several hundred leaders at Sony Europe have adopted the concepts of energy management. More than 2,000 of their direct reports will go through the energy rejuvenation programme throughout the course of the following year. Since Fujio Nishida, it has been more socially acceptable at Sony to take short breaks, exercise during the day, check e-mail only at specific times, and even inquire about the stories that irritated or impatient coworkers are telling themselves.

Changes in behaviours, communications, and rules are all part of organisational support. Many of the businesses have constructed “renewal rooms,” where people may go frequently to unwind and refuel. Some provide discounted gym memberships. In some instances, managers will gather teams of workers for lunchtime exercises. To guarantee that people have at least one hour completely free of meetings, one organisation implemented a no-meeting zone between 8 and 9 am. Senior executives at various firms, including Sony, decided to cease checking email during meetings in order to make them more productive and focused.

Many businesses have created “renewal rooms” where individuals can frequently go to unwind and replenish.

Success can be hampered by a crisis attitude, for example. Organizations that experience just enough pain to be eager for new answers but not enough to be utterly overwhelmed make the best candidates for energy renewal programmes. The senior team at one company, where we had the active support of the CEO, couldn’t tear themselves away from their focus on immediate survival despite the fact that taking time off for renewal might have allowed them to be more productive at a more sustainable level. The company was under intense pressure to grow rapidly.

In contrast, the team at Ernst & Young completed the procedure effectively during the busiest time of the tax season. They practised controlling their emotions by breathing or telling themselves other stories, with the approval of their supervisors, and they alternated moments of intense concentration with restorative pauses. The majority of the group members said that they had never felt less stressed than they did throughout this busy season.

Today, corporations and their employees have an implicit agreement that each will make every effort to get as much from the other as possible, as quickly as possible, and then move on without looking back. That is, in our opinion, mutually destructive. Instead of becoming enriched, both the individuals and the organisations they work for become deprived. Employees are becoming more and more stressed out. Organizations are compelled to accept workers who aren’t totally engaged and to continuously hire and train new employees to take the place of those who opt to depart. We propose a new, clear contract that is advantageous to all parties: To help them create and maintain their value, organisations invest in their employees across all facets of their lives. People react by bringing their entire multidimensional energy to work every day. The worth of both rises as a result.

Executive Summary

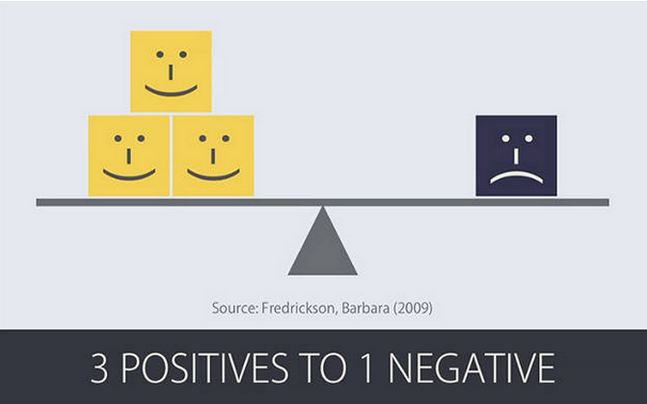

Chapter 1: Positivity Ratio

The definition of positivity and how it can change people’s lives are presented by Fredrickson in her 2009 book Positivity. At the time, research indicated that the ideal level of positivity for high-functioning teams, partnerships, and marriages was about a 3:1 ratio (this is sometimes referred to as the Losada Ratio). According to Fredrickson, having a roughly equal amount of good and negative emotions helps people reach their highest levels of resilience and well-being. The talks on how a positive frame of mind might improve relationships, health, relieve depression, and widen the mind were sparked by this scientific discovery, which was revolutionary.

The three to one positive ratio

Because of the beautiful and hard-wired design of your neural system by nature, negativity lasts longer than positive. According to research, it takes three positive experiences to make up for one negative one. For every ripping negative emotional experience you go through, at least three sincere happy emotional experiences that lift you are required, according to Dr. Barbara Fredrickson, a happiness researcher at the University of North Carolina. By using what she refers to as the 3-to-1 ratio, you may create a cooperative relationship between your survival mind and your flourish mind. According to Fredrickson, being positive does not include adhering to the axioms of “grin and bear it” or “don’t worry, be joyful.” “Those are just surface-level wishes. Optimism goes further. It includes every pleasant emotion under the sun, from admiration to love, laughter to joy, and everything in between.

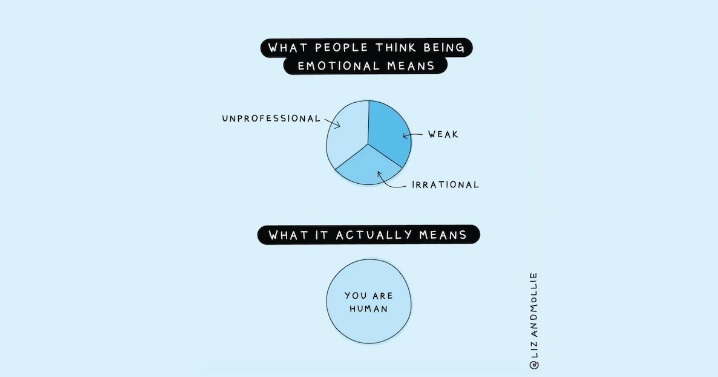

Chapter 2: Emotion Importance

In business, feelings have a terrible reputation. We’ve been trained to think they have less validity than thoughts. It’s not personal, it’s simply business, as we all know. This claim argues that objective facts trump personal feelings. However, as emotions are an integral component of the human experience, it would be foolish and impossible to exclude them from judgement, interaction, and decision-making.

Recent research (paywall) demonstrates that cognition and emotions work together to shape intention and behaviour. Humans evaluate a situation simultaneously on the cognitive and emotional levels. These evaluations lead to:

1. A feeling of well-being

2. A list of goals for the person’s behaviour in the future

In other words, the mind processes both thought and emotion, deciding if the circumstance is favourable or unfavourable, and then deciding how to respond. In terms of how it relates to business, there are two key conclusions from this neuroscience research:

1. The brain does not manage cognition and emotion separately.

2. Employee goal-setting and organisational outcomes are significantly impacted by the intentions that emerge (through the assessment process).

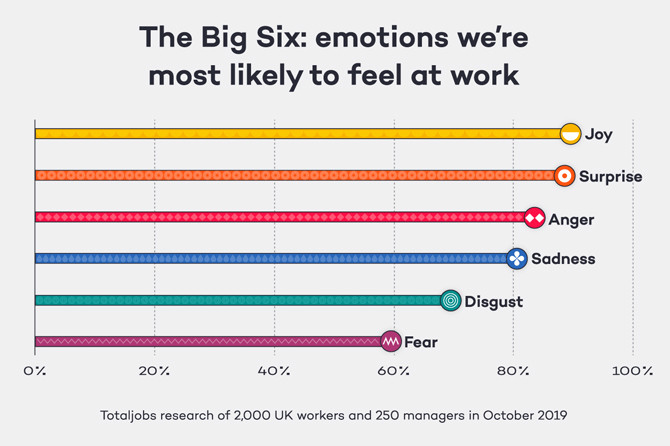

Consider the following scenarios: A coworker (and friend) is abruptly fired; you are given an impossible task; or the project you firmly believe in is shelved after months of work. The most frequent negative emotions felt at work are worry, unhappiness, frustration, and rage, therefore any of these circumstances could leave you feeling one of these ways.

Whether you realise it or not, these feelings may make you feel threatened, and that feeling may cause you to use less of your free time, be less kind to your coworkers, consider leaving the company, or second-guess your support for it or its leaders. Detrimental emotions can have negative effects that must not be ignored. They have an effect on a company’s bottom line in addition to your energy quality.

On the other hand, Barbara Fredrickson’s research on positive emotions demonstrates that positive affect not only predicts future happiness and success, but also reflects present safety, contentment, and achievement. Positive emotion cultivation over time (at least a 3:1 ratio) has a “broaden-and-build” effect on the person doing it. Positive emotion expression makes room for new opportunities, abilities, relationships, and knowledge.

It begs us all to pay more attention to it since work is rife with opportunities for emotion and because employees make decisions with both their perceiving hearts and their reasoning heads.

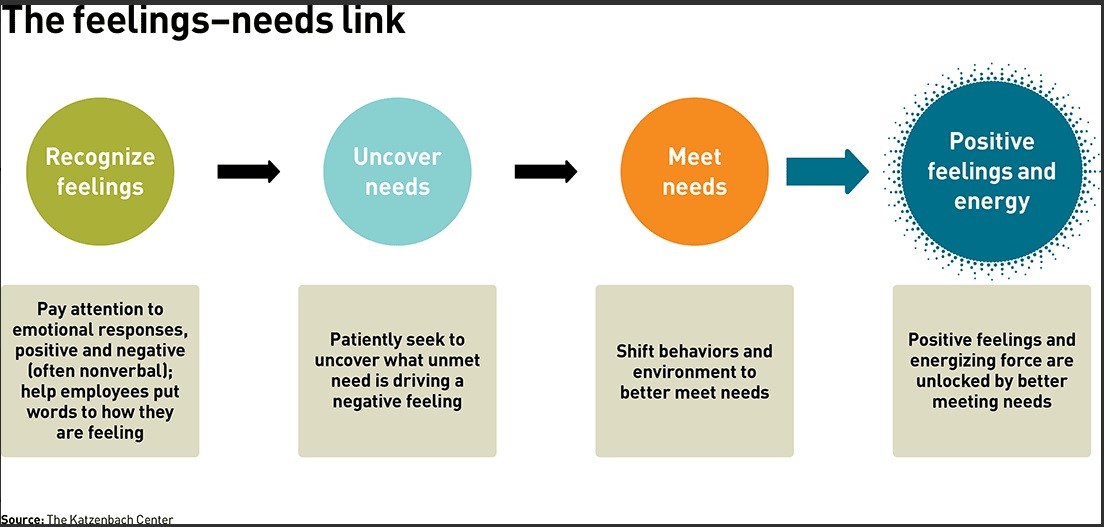

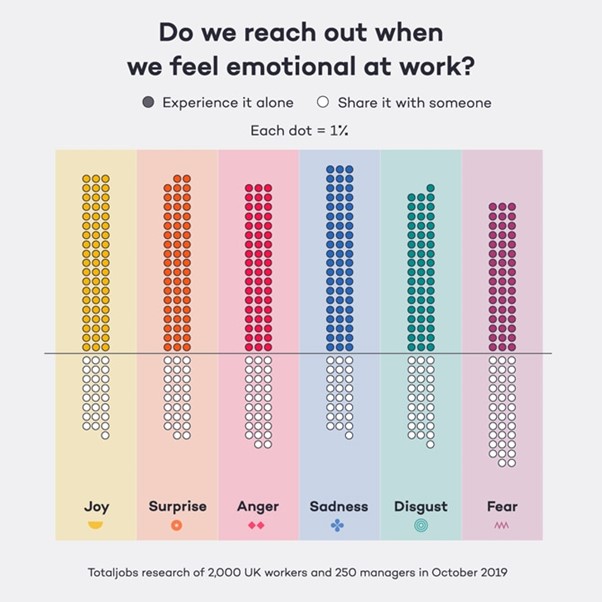

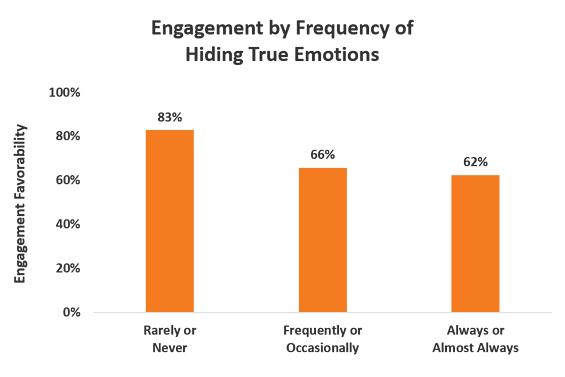

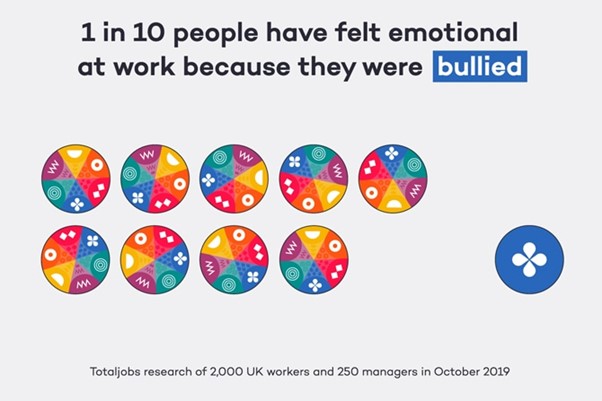

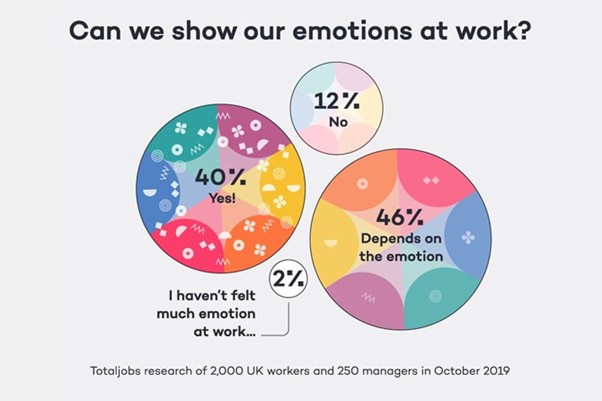

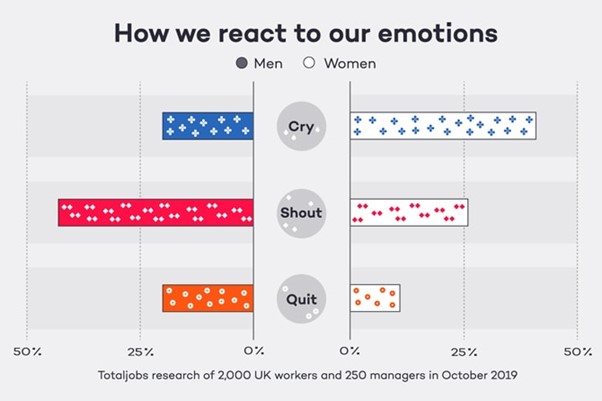

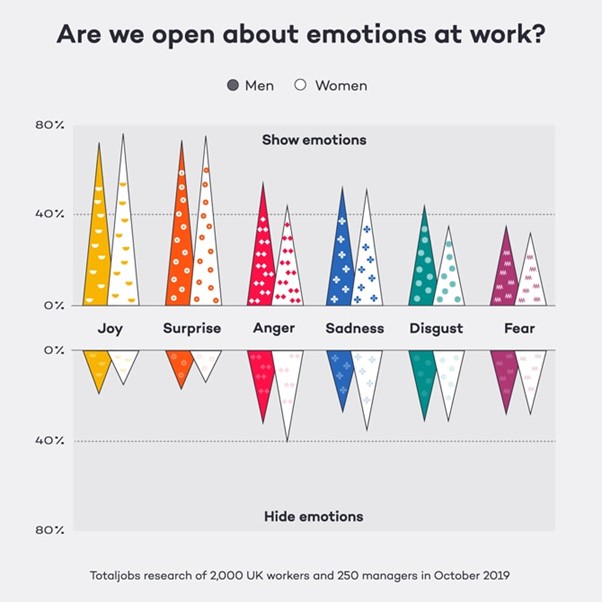

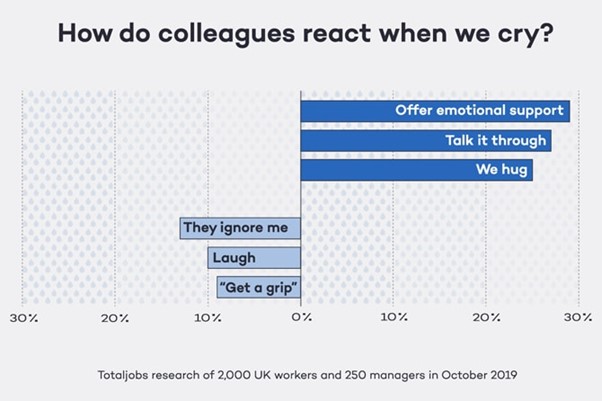

Chapter 3: Workplace Emotions

Although it can be simple for managers to dismiss feelings at work, doing so can have serious repercussions. It goes without saying that feelings are important in the job. Stress, anger, or other negative emotions can impair a person’s ability to function at work and interact with others. It’s critical for managers to understand these feelings and how to handle them. Managers can cultivate a healthy work environment for their team and support their success by comprehending and acknowledging the significance emotions play in the workplace.

Why Are Emotions Important at Work?

It may be possible to predict workplace outcomes by looking at the emotional climate there. Here are some basic ways that workplace emotions impact an organisation:

• Top talent is attracted to a happy workplace because it fosters higher retention rates and loyalty to the business in addition to attracting the best candidates.

• It’s possible to have too much of a good thing, which can impair critical thinking and decrease productivity.

• Stress has been demonstrated to have a negative impact on memory, attention, impulse control, and mental flexibility. Because of this, organisations that overly enforce rules or overlook the need of establishing a healthy emotional culture may find that their employees are less productive.

• Burnout is supposed to result from low morale at work over an extended length of time. Emotional depletion leads to burnout. This may be a result of a variety of professional problems, including a sense of being devalued at work, a lack of influence, or a lack of teamwork among teammates.

• Positive feelings promote innovation: People are more likely to come up with fresh ideas when they feel free to express themselves and are encouraged to take chances. And those ideas are more likely to be turned into successful goods or services when they are greeted with encouragement and enthusiasm.

What Does Emotional Intelligence Look Like at Work?

The capacity to recognise and control one’s own emotions as well as those of others is known as emotional intelligence (EI). Self-awareness, empathy, and self-control are all necessary. EI involves comprehending and controlling feelings, as opposed to conventional intelligence, which is centred on cognitive abilities.

Emotional intelligence can be a useful tool in the job for managing relationships, handling challenging talks, and resolving conflict. People with emotional intelligence are better equipped to foster a supportive and fruitful work environment.

Chapter 4: Positive Emotions

Negative emotions, such as worry, dread, and sadness, have a long history of being linked to physical and mental health problems. Recent research, however, emphasises the advantages of positive feelings including happiness, joy, awe, and gratitude that were previously underappreciated.

The relationships and effects of having pleasant emotions have been the subject of a wave of research during the last fifteen years. It is obvious that people who experience pleasant emotions frequently do better at home and at work, even if researchers are still trying to understand the precise mechanisms that connect positive emotions to these crucial outcomes.

As a result, corporate wellness initiatives that boost workplace happiness are becoming into potent instruments for achieving desired outcomes that raise general employee wellbeing and productivity.

A Better Relationship Between Positive Emotions and Better Stress Management

Recent studies have examined both happy feelings that arise naturally throughout daily living and positive emotions that are induced in a laboratory setting. In the latter, pleasant emotions can be successfully induced in a variety of ways, for instance by playing quick film segments that specifically target a desired feeling, like joy.

Overall, these research have shown that having pleasant emotions has positive effects, from better physical health to less turnover at work. Positive emotions are linked to better physical health and longer lifespans, which is one of the study’s most compelling conclusions.

Chapter 5: Negative Emotions/ Negativity Bias

What can you do, particularly when you’re feeling bad?

1. Make emotion normal.

Accept feelings as they are; don’t react or pass judgement on them. Both your own and other people’s emotions apply here. Try to embrace the emotion as neutral and natural, not good or bad. By doing this, the possibility that shame will enter the picture is reduced. All emotions should be accepted, I remind my clients, but some behaviours (violence, insults, outbursts, and tantrums) shouldn’t be.

2. Take a step back.

By not too connecting with them, unpleasant feelings might stop being unpleasant. Putting the feeling into perspective allows us to realise that it is information, not us. Writing is frequently a fantastic approach to observe and externalise feelings.

3. Conduct research on the feeling.

The first two steps should be completed before this. Study your emotion after that. Be enquiring. Even when everything makes sense, a situation may still not feel right. Look for the lessons the feeling can teach you.

Motivation, emotion, and cognition all work together to influence how people perceive and act. It undermines interpersonal efficacy, long-term performance, employee commitment, and job happiness to act as though sentiments don’t matter in the workplace. Whether you are a leader or a follower in the organisation, it is your obligation to 1) notice emotion, 2) moderate the highs and lows, and 3) integrate it into your actions so that you may act with a more positive intention, optional motivation, and awareness of the entire system.

Positive emotions can help the body by repairing the harm caused by negative emotions and stress. In other words, cheerful people seem to recover from stresses more quickly than sad people do, suggesting that positive emotions are linked to quicker recovery from stressful experiences.

Positive feelings can be a powerful weapon in the fight against stress’s cumulative effects. Additionally, studies suggest that feeling well may directly impact health through many channels.

For instance, several research have revealed a link between good emotions and stronger immune system functioning, which may affect our capacity to fend off illnesses and lower absenteeism and sick leave among workers. Regardless of the precise reasons or mechanisms involved, there is a clear and convincing link between happiness and good health.

Chapter 6: Emotional Triggers

You likely go through a range of feelings every day, including excitement, anxiety, irritation, joy, and disappointment. These frequently have to do with certain occasions, such meeting your employer, discussing the news with a friend, or running into your partner.

Depending on your state of mind and the situational factors, your reaction to these experiences may differ.

Whatever your current mood, an emotional trigger is anything that causes a strong emotional response, including memories, experiences, or events.

A crucial element of having excellent emotional health is understanding your emotional triggers (and how to deal with them).

It’s not always simple to remain composed and serene while working. Daily emotional events include unanticipated remarks that ruin your mood, tough supervisors, annoying coworkers, and making blunders. It can be challenging to maintain composure when these things occur in public situations, particularly if your internal resources are already low.

Despite this obstacle, maintaining composure in the face of tense circumstances is the essence of executive presence, or the capacity to encourage others to have faith in you. To communicate thoughtfully and achieve your desired results, you must control when and how you process your emotions. Here, it’s advised not to brush your emotions under the rug. In order to respond in ways that help you both in the present and after it has passed, you must learn to pause and obtain the clarity you need. It won’t be possible to temporarily vanish by turning off your camera as more teams return to the office.

Chapter 7: Emotional Control

Working with emotions can be challenging.

You can discover that while your emotions sometimes motivate you to take positive action, other times they push you to self-destruct.

The idea of “opposite action” is one strategy for managing strong emotions at work.

This psychological notion encourages us to embrace and manage our emotions as opposed to suppressing them.

The phrase “opposite action” means exactly what it says. By acting in opposition to what our emotions are telling us to do, we can reroute strong emotions toward healthy behaviour.

Let’s look at an instance of receiving unfavourable comments:

Determine the impulse that goes along with the feelings you’re feeling.

Let’s assume that you often experience disappointment when your supervisor offers suggestions for how to make your presentation better. What memories come to mind when you think back to past periods in your life when you frequently felt deeply disappointed? What behaviours or compulsions did you see yourself having? You probably had the need to hide or run. Perhaps you spent hours crying in your bedroom after receiving a poor mark on a report card. Maybe you still feel the impulse to run away and hide as an adult when you receive unfavourable criticism.

Analyze the urge to see if it is appropriate.

You can avoid speaking with your supervisor out of a desire to retreat after being disappointed. The next time you see her walking down the hall, you might consider hiding into a conference room, or you might consider taking a few days off work to recover from the setback. Ask yourself if carrying out either of those activities would be in your best interests.

Chapter 8: Group Emotional Intelligence

Like every social group, a team develops its own personality. Therefore, it takes more than a few people to behave in an emotionally intelligent manner for a group to experience an upward, self-reinforcing spiral of trust, group identity, and group efficacy. It requires a team environment where the norms foster emotional capacity (the capability to respond constructively in emotionally taxing situations) and positively shape emotions.

Because teams interact at more levels than individuals do, team emotional intelligence is more complex than individual emotional intelligence. Let’s first examine Daniel Goleman’s definition of the term “individual emotional intelligence” to better comprehend the distinctions. Goleman describes the key traits of someone with high emotional intelligence in his seminal book Emotional Intelligence: awareness of emotions and the capacity to control them, directed both within, toward oneself, and outward, toward others. According to Goleman, being conscious of and in control of one’s own emotions is the foundation of “personal competence.” Awareness and control of other people’s emotions are components of “social competence.”

However, a group must pay attention to still another degree of awareness and control. It must be aware of its own group moods and emotions as well as the moods of other groups and people living outside of its borders.

We’ll look at how dysfunction can result from emotional inadequacy at any of these levels in this course manual. We’ll also demonstrate how adopting particular group rules that foster emotional awareness and management at these three levels can produce better results. We’ll start by concentrating on the individual level—how emotionally intelligent groups manage the emotions of each of their individual members. We’ll then concentrate on the group level. We’ll examine the cross-boundary level lastly.

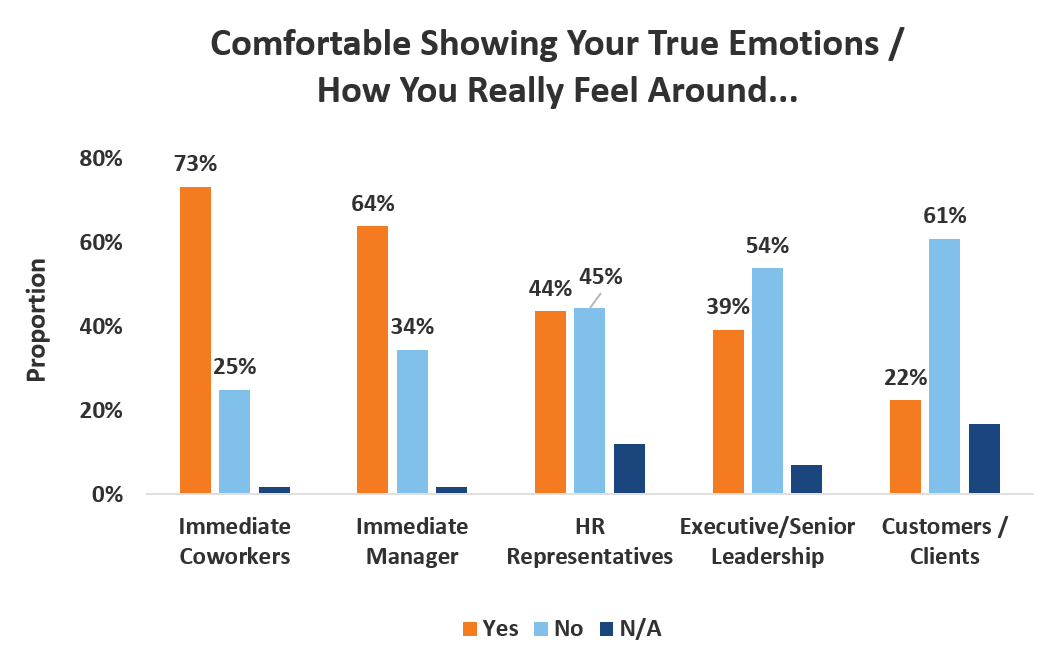

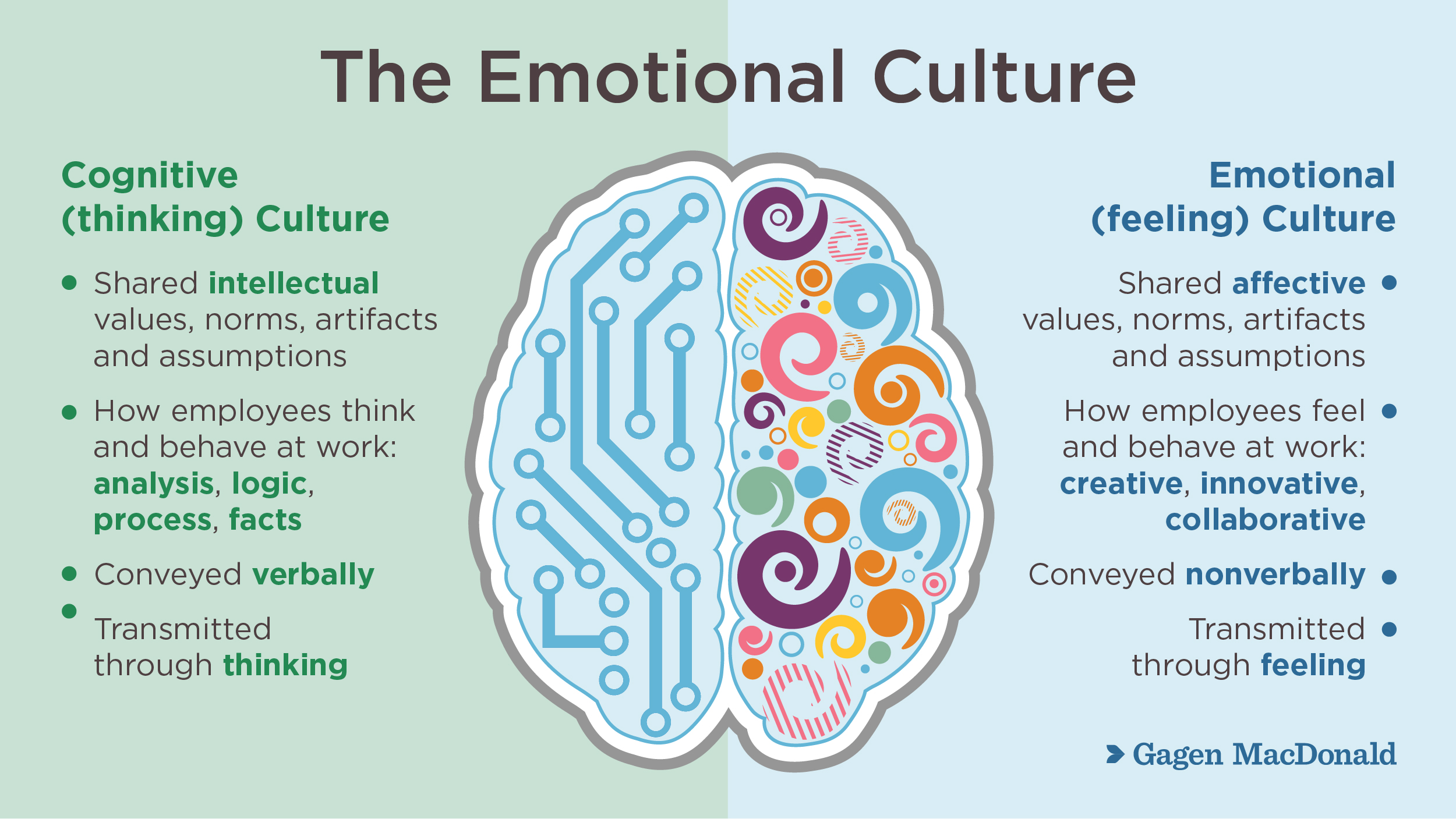

Chapter 9: Emotional Culture

In your role as a leader, managing your emotions as a result of stressful situations at work extends to your personal life as well. People are complicated, and they have many different needs. While promoting your employees’ emotional well-being may seem like a therapist’s job, doing so is essential for the success of your business. Assessing your emotional culture is the first step in developing a workplace that is emotionally safe.

“Shared affective values, norms, artefacts, and assumptions” are what is meant by “emotional cultures,” and they dictate which emotions people are allowed to experience and express at work and which ones they should stifle. While some businesses embrace emotions wholeheartedly, others prefer to avoid them at all costs. Finding your organization’s position on the spectrum and choosing your course of action are crucial.

To identify your potential for emotional development, ask your leadership team to consider these questions.

• If you primarily selected “Always” or “Usually,” congratulations! The strong emotional culture that your company is fostering for its employees is admirable.

• It’s acceptable if you largely checked “Unsure,” but it’s not acceptable to remain in the dark. If you want to start changing the emotional climate of your company, take a look at the actions listed below.

• These are emotional culture red flags if you marked “Rarely” or “Never” the majority of the time. Your organization’s leaders ought to take these issues into consideration.

If you’ve discovered yourself on the “struggle bus,” don’t worry! Here are 3 ideas for building an emotionally supportive organisational culture that is powerful.

1. To promote positive expression

Imagine that you are inflating a balloon. The balloon will ultimately run out of room to grow as you add more air, and it will pop. This is what it could look like to hold your feelings within. Consider the effects that pressure might have on your staff.

Studies have revealed that suppressing those feelings can result in a number of health hazards, such as:

o Heart Disease

o Mental Illness

o Intestinal Problems

o Headaches

o Insomnia

o Autoimmune disorders

Emotions and feelings from the past are now physical health problems. the kinds of problems that have an impact on the productivity of your business and ultimately your bottom line. People would probably feel uneasy and disengaged if they don’t know how to convey their emotions effectively.

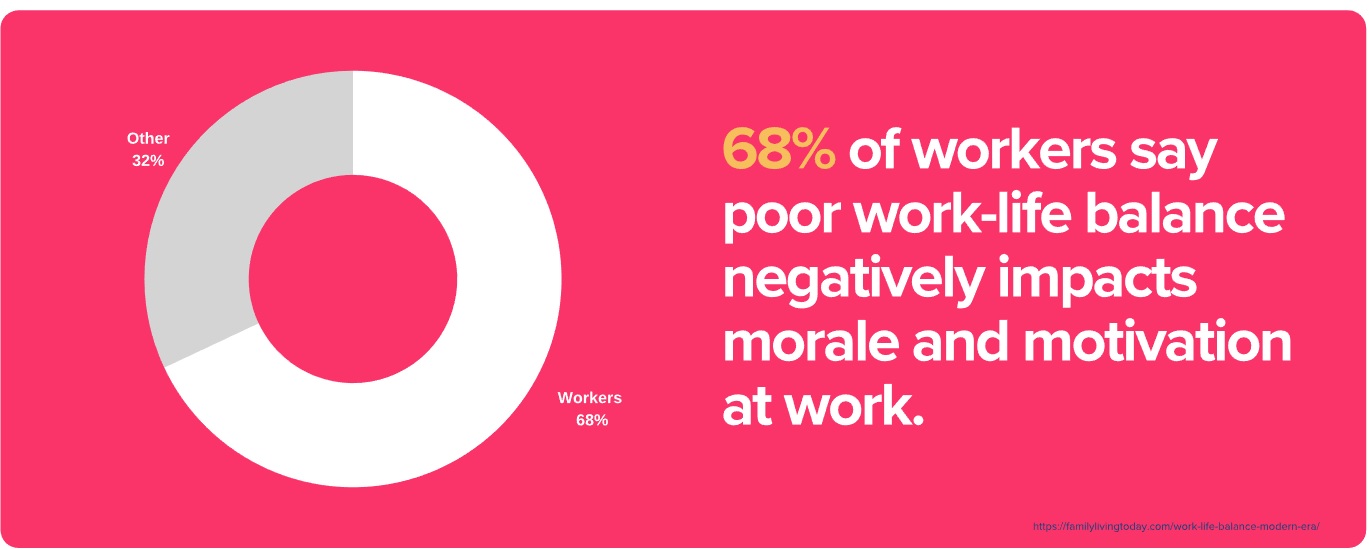

Motivate staff to prioritise finding a work-life balance.

Strong emotional cultures recognise how difficult it is to separate one’s personal and professional lives. Encourage your staff to schedule activities that will enhance every facet of their personal wellbeing.

2. Ensure Communication

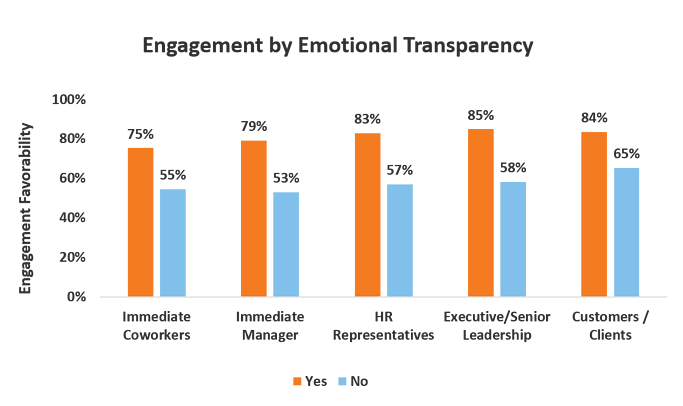

According to our research, there is room for improvement in major firms’ change communication. Employees feel excluded from their work and the organisation when leadership doesn’t include them in crucial decisions. Because of this, workers frequently experience a lack of human attention and frequently engage in gossip.

Make a commitment to engaging in frank and straightforward dialogue with everyone in your business. Give your staff a range of opportunities to learn about and react to changes taking place at work. Have regular talks with your direct reports and encourage staff to voice their issues at one-on-one sessions.

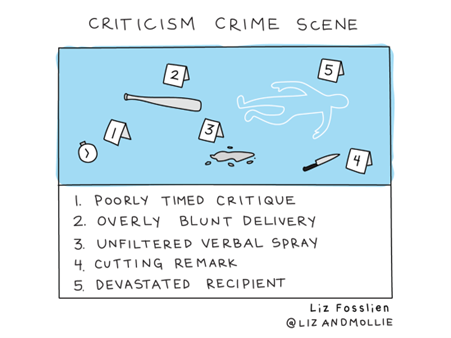

3. Improve Feedback

Asking for input is a terrific method to find out why your staff members are feeling certain ways. Managers that understand the value of routinely communicating with staff members and taking the time to listen are better equipped to solve issues before they worsen.

Ask for input from workers at all levels whenever something seems off or a tense scenario develops. Your staff will be able to voice their worries and handle their emotions more effectively if you do this. In your engagement and pulse surveys, take into account incorporating pertinent questions.

Chapter 10: Increasing Positivity

The value of having an optimistic outlook in work

The value of having a positive outlook might seem obvious, but it’s so simple to get sucked into our own problems and dramas. You have to make an effort to avoid being negative during those moments, whether you or a coworker is experiencing hardship.

Negativity has never helped anyone succeed, according to Deborah Sweeney, CEO of MyCorporation. When you are among positive people, you feel better. They exhort you to aim high, put in a lot of effort, and maintain your dedication to achieving your goals. It is contagious to be positive. Over time, you might discover that due to your positive attitude, even the most obstinate employee who refuses to appreciate something changes their mind and becomes more upbeat.

Saying yes is a simple way to demonstrate a positive attitude at work.

Positivity is simple to preach. It’s harder to put it into action and be sincere about it.

The words you use might convey your mood, according to Sweeney. “Try new things and learn to say “yes” to everything. If you have some free time, offer your time and ask coworkers how you can assist them. Offer to lead new projects on your own initiative. Be truthful and kind to everyone; avoid persistent gossip and rumor-mongering.

Positive individuals, according to keynote speaker Rachel Sheerin on burnout and happiness, exude a certain energy.

She claimed that positive people exhibit their positive attitude through their words, deeds, and feelings. “Positive people radiate differently; they affect the world and the people around them just by entering the room with their energy.”

Experts generally agree that having a happy attitude is all about how you carry yourself. According to motivational speaker and personal development coach Jessi Beyer, a grin may lift the spirits of the entire office as opposed to a glum expression. She added that how you respond to circumstances and interact with coworkers can have a significant impact.

Chapter 11: Resilience

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that a quarter of all workers consider their jobs to be their biggest stressor. The “global health epidemic of the 21st century” is stress, according to the World Health Organization. Many of us today work in highly demanding, always-on, continuously linked work environments where stress and the risk of burnout are common. Building resilience skills is more crucial than ever to successfully navigate your worklife because the pace and intensity of today’s workplace culture are not likely to alter.

In previous roles as director of learning and organisation development at Google, eBay, and J.P. Morgan Chase, as well as in my current role as co-founder of the learning solutions company Wisdom Labs, I have repeatedly observed that the most resilient people and teams are those that fail, learn from it, and go on to succeed. Being tested, sometimes harshly, is one of the factors that makes resilience as a skill set active.

The building blocks of resilience include attitudes, behaviours, and social supports that anybody can acquire and cultivate, according to more than five decades of research. Optimism, the capacity to maintain equilibrium and control over strong or challenging emotions, a sense of safety, and a robust social support network are all factors that contribute to resilience. The good news is that you can learn to be more resilient since there is a specific set of behaviours and skills linked to resilience.

Being optimistic inside develops a coping strategy for emotional resilience. In other words, a resilient worker always recovers by feeling good.

Your cognitive and social flexibility are increased.

based on a study, “Positive emotions increase the range of possible actions and thoughts, which should “erase” the residual cardiovascular effects of negative emotions. Therefore, it seems to have a special capacity to biologically down-regulate persistent unpleasant feelings.”

Positive feelings so cultivate resilience, which can aid workers in broadening their perspective to one of deliberation. Employees become mentally fit as well as emotionally robust as a result.

Chapter 12: Team Performance

According to a study, high-performing teams often experience 16% less rage at work than low-performing teams, which typically experience a high of 30%. When compared to low-performing teams, high-performing teams frequently feel twice as many good emotions.

As a result, your team will be more productive if everyone is happy with the work you are doing together. Emotions play a significant role on both individual and team performance.

Employees who lack an emotional connection to their work or to the workplace will never be able to produce positive results. Additionally, it will negatively affect your performance and level of motivation.

Employee emotions must be valued in the workplace.

People work with their coworkers for about half of the day, sharing a portion of their lives.

Can you picture your office with people who have no common interests, are neither enjoyable nor interesting and spend the entire day working? Or can you picture working from 9 to 5 somewhere where nobody talks about anything but work?

No, is the response. The vast majority of people favour working in an environment that promotes health and fresh ideas.

Better communication is the only way to improve your working relationships. Make sure the workplace is free of harmful substances for your staff.

People that share interests and appreciate one another’s ideas make a solid team. Any company where a worker’s good emotion is acknowledged is always on the road to success.

Curriculum

Emotional Competence – Workshop 1 – 24hr Emotions

- Positivity Ratio

- Emotion Importance

- Workplace Emotions

- Positive Emotions

- Negative Emotions

- Emotional Triggers

- Emotional Control

- Group Emotional Intelligence

- Emotional Culture

- Increasing Positivity

- Resilience

- Team Performance

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Emotional Competence corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast

As a guide, the Appleton Greene Emotional Competence corporate training program should take 12-18 months to complete, depending upon your availability and current commitments. The reason why there is such a variance in time estimates is because every student is an individual, with differing productivity levels and different commitments. These differentiations are then exaggerated by the fact that this is a distance-learning program, which incorporates the practical integration of academic theory as an as a part of the training program. Consequently all of the project studies are real, which means that important decisions and compromises need to be made. You will want to get things right and will need to be patient with your expectations in order to ensure that they are. We would always recommend that you are prudent with your own task and time forecasts, but you still need to develop them and have a clear indication of what are realistic expectations in your case. With reference to your time planning: consider the time that you can realistically dedicate towards study with the program every week; calculate how long it should take you to complete the program, using the guidelines featured here; then break the program down into logical modules and allocate a suitable proportion of time to each of them, these will be your milestones; you can create a time plan by using a spreadsheet on your computer, or a personal organizer such as MS Outlook, you could also use a financial forecasting software; break your time forecasts down into manageable chunks of time, the more specific you can be, the more productive and accurate your time management will be; finally, use formulas where possible to do your time calculations for you, because this will help later on when your forecasts need to change in line with actual performance. With reference to your task planning: refer to your list of tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve your program objectives; with reference to your time plan, calculate when each task should be implemented; remember that you are not estimating when your objectives will be achieved, but when you will need to focus upon implementing the corresponding tasks; you also need to ensure that each task is implemented in conjunction with the associated training modules which are relevant; then break each single task down into a list of specific to do’s, say approximately ten to do’s for each task and enter these into your study plan; once again you could use MS Outlook to incorporate both your time and task planning and this could constitute your study plan; you could also use a project management software like MS Project. You should now have a clear and realistic forecast detailing when you can expect to be able to do something about undertaking the tasks to achieve your program objectives.

Performance management

It is one thing to develop your study forecast, it is quite another to monitor your progress. Ultimately it is less important whether you achieve your original study forecast and more important that you update it so that it constantly remains realistic in line with your performance. As you begin to work through the program, you will begin to have more of an idea about your own personal performance and productivity levels as a distance-learner. Once you have completed your first study module, you should re-evaluate your study forecast for both time and tasks, so that they reflect your actual performance level achieved. In order to achieve this you must first time yourself while training by using an alarm clock. Set the alarm for hourly intervals and make a note of how far you have come within that time. You can then make a note of your actual performance on your study plan and then compare your performance against your forecast. Then consider the reasons that have contributed towards your performance level, whether they are positive or negative and make a considered adjustment to your future forecasts as a result. Given time, you should start achieving your forecasts regularly.

With reference to time management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual time taken in your study plan; consider your successes with time-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; consider your failures with time-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to time planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your time expectations. You need to be consistent with your time management, otherwise you will never complete your studies. This will either be because you are not contributing enough time to your studies, or you will become less efficient with the time that you do allocate to your studies. Remember, if you are not in control of your studies, they can just become yet another cause of stress for you.

With reference to your task management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual tasks that you have undertaken in your study plan; consider your successes with task-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case; take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; consider your failures with task-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to task planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your task expectations. You need to be consistent with your task management, otherwise you will never know whether you are achieving your program objectives or not.

Keeping in touch

You will have access to qualified and experienced professors and tutors who are responsible for providing tutorial support for your particular training program. So don’t be shy about letting them know how you are getting on. We keep electronic records of all tutorial support emails so that professors and tutors can review previous correspondence before considering an individual response. It also means that there is a record of all communications between you and your professors and tutors and this helps to avoid any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation. If you have a problem relating to the program, share it with them via email. It is likely that they have come across the same problem before and are usually able to make helpful suggestions and steer you in the right direction. To learn more about when and how to use tutorial support, please refer to the Tutorial Support section of this student information guide. This will help you to ensure that you are making the most of tutorial support that is available to you and will ultimately contribute towards your success and enjoyment with your training program.

Work colleagues and family

You should certainly discuss your program study progress with your colleagues, friends and your family. Appleton Greene training programs are very practical. They require you to seek information from other people, to plan, develop and implement processes with other people and to achieve feedback from other people in relation to viability and productivity. You will therefore have plenty of opportunities to test your ideas and enlist the views of others. People tend to be sympathetic towards distance-learners, so don’t bottle it all up in yourself. Get out there and share it! It is also likely that your family and colleagues are going to benefit from your labors with the program, so they are likely to be much more interested in being involved than you might think. Be bold about delegating work to those who might benefit themselves. This is a great way to achieve understanding and commitment from people who you may later rely upon for process implementation. Share your experiences with your friends and family.

Making it relevant

The key to successful learning is to make it relevant to your own individual circumstances. At all times you should be trying to make bridges between the content of the program and your own situation. Whether you achieve this through quiet reflection or through interactive discussion with your colleagues, client partners or your family, remember that it is the most important and rewarding aspect of translating your studies into real self-improvement. You should be clear about how you want the program to benefit you. This involves setting clear study objectives in relation to the content of the course in terms of understanding, concepts, completing research or reviewing activities and relating the content of the modules to your own situation. Your objectives may understandably change as you work through the program, in which case you should enter the revised objectives on your study plan so that you have a permanent reminder of what you are trying to achieve, when and why.

Distance-learning check-list

Prepare your study environment, your study tools and rules.

Undertake detailed self-assessment in terms of your ability as a learner.

Create a format for your study plan.

Consider your study objectives and tasks.

Create a study forecast.

Assess your study performance.

Re-evaluate your study forecast.

Be consistent when managing your study plan.

Use your Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) for tutorial support.

Make sure you keep in touch with those around you.

Tutorial Support

Programs

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. They are implemented over a sustainable period of time and professional support is consistently provided by qualified learning providers and specialist consultants.

Support available

You will have a designated Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and an Accredited Consultant and we encourage you to communicate with them as much as possible. In all cases tutorial support is provided online because we can then keep a record of all communications to ensure that tutorial support remains consistent. You would also be forwarding your work to the tutorial support unit for evaluation and assessment. You will receive individual feedback on all of the work that you undertake on a one-to-one basis, together with specific recommendations for anything that may need to be changed in order to achieve a pass with merit or a pass with distinction and you then have as many opportunities as you may need to re-submit project studies until they meet with the required standard. Consequently the only reason that you should really fail (CLP) is if you do not do the work. It makes no difference to us whether a student takes 12 months or 18 months to complete the program, what matters is that in all cases the same quality standard will have been achieved.

Support Process

Please forward all of your future emails to the designated (CLP) Tutorial Support Unit email address that has been provided and please do not duplicate or copy your emails to other AGC email accounts as this will just cause unnecessary administration. Please note that emails are always answered as quickly as possible but you will need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general tutorial support emails during busy periods, because emails are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. You will also need to allow a period of up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Please therefore kindly allow for this within your time planning. All communications are managed online via email because it enables tutorial service support managers to review other communications which have been received before responding and it ensures that there is a copy of all communications retained on file for future reference. All communications will be stored within your personal (CLP) study file here at Appleton Greene throughout your designated study period. If you need any assistance or clarification at any time, please do not hesitate to contact us by forwarding an email and remember that we are here to help. If you have any questions, please list and number your questions succinctly and you can then be sure of receiving specific answers to each and every query.

Time Management

It takes approximately 1 Year to complete the Emotional Competence corporate training program, incorporating 12 x 6-hour monthly workshops. Each student will also need to contribute approximately 4 hours per week over 1 Year of their personal time. Students can study from home or work at their own pace and are responsible for managing their own study plan. There are no formal examinations and students are evaluated and assessed based upon their project study submissions, together with the quality of their internal analysis and supporting documents. They can contribute more time towards study when they have the time to do so and can contribute less time when they are busy. All students tend to be in full time employment while studying and the Emotional Competence program is purposely designed to accommodate this, so there is plenty of flexibility in terms of time management. It makes no difference to us at Appleton Greene, whether individuals take 12-18 months to complete this program. What matters is that in all cases the same standard of quality will have been achieved with the standard and bespoke programs that have been developed.

Distance Learning Guide

The distance learning guide should be your first port of call when starting your training program. It will help you when you are planning how and when to study, how to create the right environment and how to establish the right frame of mind. If you can lay the foundations properly during the planning stage, then it will contribute to your enjoyment and productivity while training later. The guide helps to change your lifestyle in order to accommodate time for study and to cultivate good study habits. It helps you to chart your progress so that you can measure your performance and achieve your goals. It explains the tools that you will need for study and how to make them work. It also explains how to translate academic theory into practical reality. Spend some time now working through your distance learning guide and make sure that you have firm foundations in place so that you can make the most of your distance learning program. There is no requirement for you to attend training workshops or classes at Appleton Greene offices. The entire program is undertaken online, program course manuals and project studies are administered via the Appleton Greene web site and via email, so you are able to study at your own pace and in the comfort of your own home or office as long as you have a computer and access to the internet.

How To Study

The how to study guide provides students with a clear understanding of the Appleton Greene facilitation via distance learning training methods and enables students to obtain a clear overview of the training program content. It enables students to understand the step-by-step training methods used by Appleton Greene and how course manuals are integrated with project studies. It explains the research and development that is required and the need to provide evidence and references to support your statements. It also enables students to understand precisely what will be required of them in order to achieve a pass with merit and a pass with distinction for individual project studies and provides useful guidance on how to be innovative and creative when developing your Unique Program Proposition (UPP).

Tutorial Support