Destination Resilience – Workshop 1 (Roadmap to Resilience)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Destination Resilience is provided by Mr. Wetter Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Mr. Wetter holds a Master’s Degree in Business Management from Münster University, Germany. Before he founded his Management Holding, he looked back on a successful career in Europe. During the last 20 years he gained major experiences in several industries. As leading manager, he worked in the Consumer and Media Industry for Top-Management. Since the last years, he specializes in Cyber Security Management and serves as a Lieutenant Colonel in the German Armed Forces Reserve, Cyber Command. As a pilot he loves to travel fast, he embraces lifelong teaching and learning, guided by the motto:

“semper gradum praemisit – always one step ahead”

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

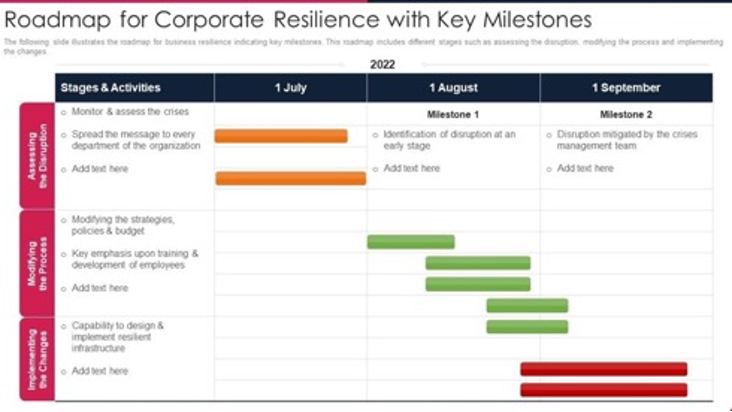

The roadmap to resilience starts with the definition of resilience itself. Key performance indicators and measurements will be discussed and set into the context of your company. Understanding the general resilience cycle is key for any further discussion and will help your team in any case, whether it is business or just for living. During the second part of the first module, we will focus on cyber resilience and break it down. Therefore, we need to discuss different types of cyber threats and areas of protection like trust, integrity and authentication. With the Sony Picture Case we will analyze how a cyberattack effects companies and which critical stages a company must go through. With the practice “analyze areas of mitigations” all candidates will be sensibilized and motivated for the follow up workshops. Each module will end with a short evaluation to adjust the following workshop. We want the roadmap to resilience your individual roadmap and can adapt focus areas from workshop to workshop.

Objectives

01. Resilience Defined: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Resilience Cycle: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Cybersecurity vs. Cyber Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Anatomy of a Crisis: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Resilience Evolution: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Organizational Structure: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Resilient Command Model: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Measuring Resilience: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Resilience Leadership: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Self-Assessment: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

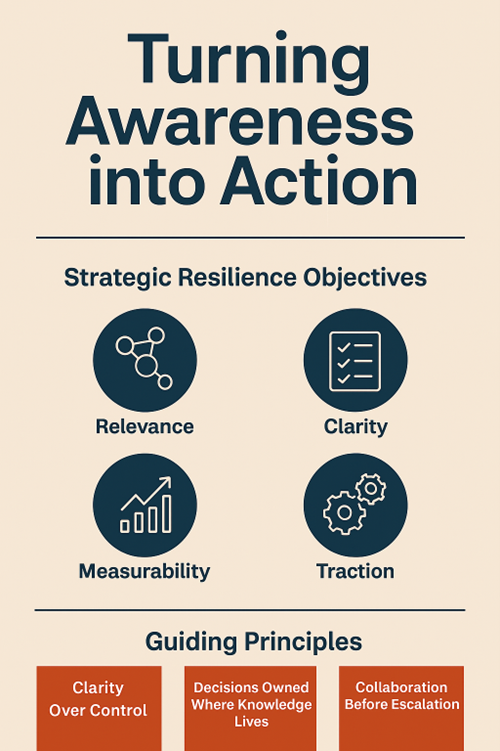

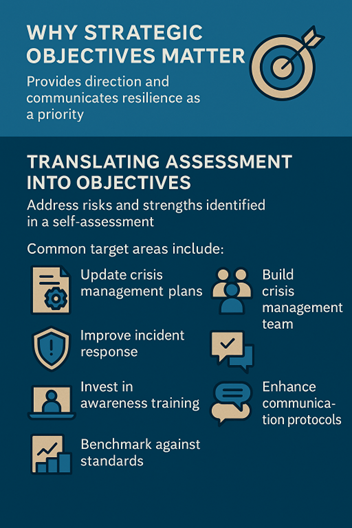

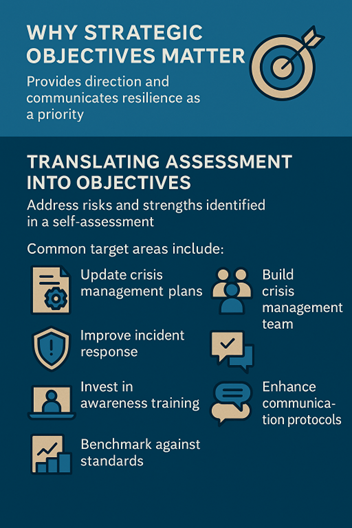

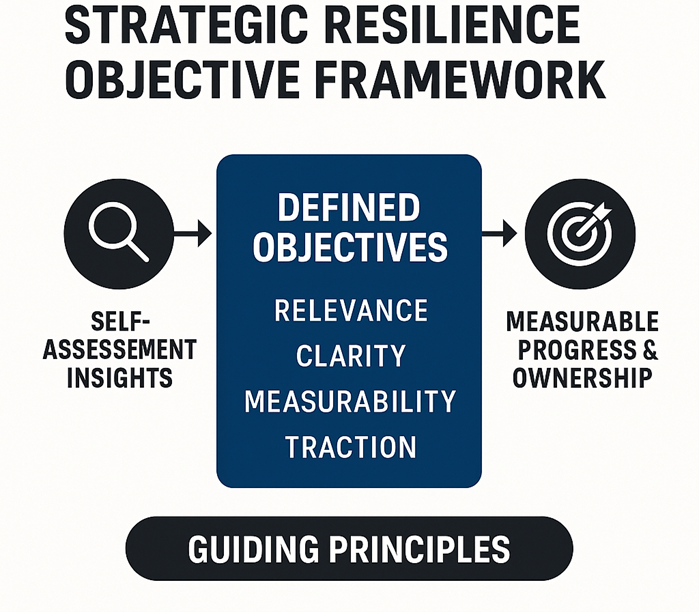

11. Strategic Resilience Objectives: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Synthesis & Expectations: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Resilience Defined: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Resilience Cycle: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Cybersecurity vs. Cyber Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Anatomy of a Crisis: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Resilience Evolution: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Organizational Structure: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Resilient Command Model: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Measuring Resilience: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Resilience Leadership: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Self-Assessment: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Strategic Resilience Objectives: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Synthesis & Expectations: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Resilience Defined.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Resilience Cycle.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Cybersecurity vs. Cyber Resilience.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Anatomy of a Crisis.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Resilience Evolution.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Organizational Structure.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Resilient Command Model.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Measuring Resilience.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Resilience Leadership.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Self-Assessment.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Strategic Resilience Objectives.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Synthesis & Expectations.

Introduction

Awakening Resilience – The First Step on a Transformational Journey

There are words that echo through every era of history, rising to prominence whenever the world seems to be in flux. In the past, terms like efficiency, innovation, or control were prized above all. Today, in a world defined by sudden shocks, relentless turbulence, and accelerating complexity, a new word has claimed center stage: resilience.

Resilience is not merely a trend. It is a profound shift in how we understand success and survival. Organizations have always faced hardship – fires, floods, wars, economic crises – but never before has the velocity and interdependence of disruption been so pervasive. Our age is shaped by invisible digital threats, supply chains that cross continents, social movements amplified in real time, and natural events that reverberate across the globe. For those leading companies, agencies, and institutions, it has become clear that the future belongs not to those who can predict every risk, but to those who can respond, adapt, recover, and grow, no matter what the world throws at them.

This workshop is your portal into the discipline of resilience. It is the first of a series of intensive one-day workshops, each designed as both a deep dive and a launching pad. On this first day, you will engage with twelve foundational dimensions of resilience, each a doorway to a new way of seeing, thinking, and acting. But the journey does not end when the day is over. What you learn here will be woven into the fabric of your daily reality for a full month, as you and your colleagues apply, test, and refine each lesson within your own teams and functions. In this way, resilience moves from theory to lived experience, from aspiration to action.

The Age of Disruption: Why Resilience, Why Now?

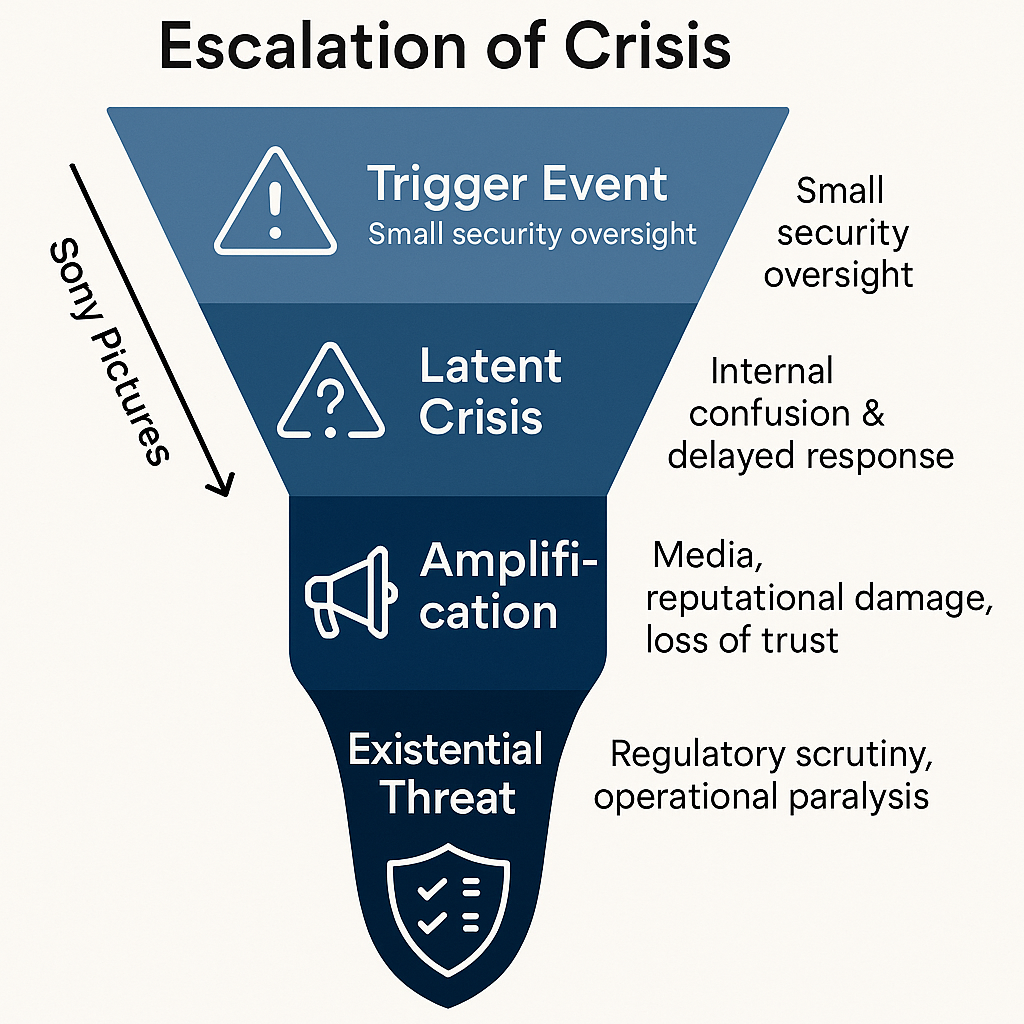

To understand the necessity of resilience, we must first confront the world as it is. Never in history have organizations faced such a relentless barrage of unpredictable events. Just within the past decade, a single cyberattack unleashed from an obscure accounting software in Ukraine brought global shipping giants like Maersk to a halt, demonstrating how a vulnerability in one corner of the world can trigger chaos everywhere. The Sony Pictures Hack became a parable for how gaps in crisis response and leadership can magnify technical incidents into existential threats, laying bare emails, scripts, and the private lives of employees for all the world to see.

Figure 01: The Sony Pictures Hack – Escalation of a Crisis

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced organizations large and small to reinvent themselves overnight – sending workforces home, retooling supply chains, upending business models, and requiring leaders to make agonizing decisions with no clear playbook. The world learned that no plan survives first contact with reality, and that resilience is not a luxury, but a matter of existential importance.

Such stories are not exceptions. They are the new normal. Digital transformation means that every organization is now, in some way, a technology company, and with that comes new forms of risk. Climate change, demographic shifts, and social upheavals further ensure that no industry, market, or geography is immune. The days of linear change and incremental improvement are gone. The only constant is surprise.

It is in this crucible that resilience becomes the ultimate competitive advantage. It is the trait that separates those who endure, adapt, and thrive from those who stumble and fade. Resilience is not about bouncing back to where you were; it is about bouncing forward to where you need to be. It is the process of turning crisis into opportunity, of transforming scars into strength.

The Evolution of Resilience: From Battlefield to Boardroom

To appreciate what resilience means today, it helps to look to its origins. In its earliest forms, resilience was born in the crucible of war and disaster. Military strategists learned that the best-laid plans were often rendered obsolete by the fog of conflict, and so they developed doctrines centered on redundancy, flexibility, and rapid improvisation. The concept of “mission command” – giving local commanders the authority and intent to adapt as situations changed – became a hallmark of resilient armies.

As societies industrialized, resilience found its way into the design of bridges, buildings, and critical infrastructure. Engineers spoke of “fail-safe” systems, backup generators, and the importance of learning from every accident or collapse. Civil defence agencies practiced for scenarios that were unthinkable – nuclear attack, chemical spills, widespread floods – because they knew that hope was not a strategy.

With the rise of global business, these lessons migrated into the language of the boardroom. Suddenly, organizations realized they were only as strong as their weakest link, as adaptable as their most empowered frontline worker. They began to invest in business continuity, disaster recovery, and risk management. But for many, these efforts remained siloed and static, focused on compliance and checklists rather than on living, breathing capability.

The digital revolution upended everything again. Cyber risk could cross borders at the speed of light. Brand reputation could be destroyed with a single viral video. Traditional crisis response was found wanting; agility, learning, and adaptability became the new watchwords. Today, the most advanced organizations understand that resilience is not a function or a department, but a mindset and a muscle – one that must be exercised and renewed at every level.

Setting the Stage: The Workshop as a Living Laboratory

This first workshop is not a lecture, a briefing, or a compliance exercise. It is an invitation to roll up your sleeves, confront uncomfortable truths, and begin the real work of building resilience – together. Each of the twelve topics you will engage with has been chosen because it represents an essential pillar in the architecture of organizational resilience.

You will begin by exploring the true meaning of resilience – not just as a technical capacity, but as a living force shaped by meaning, mindset, and mission. You will reflect on what matters most in your context, what drives your team in moments of stress, and how your mission can become a north star in times of uncertainty. You will then move into the systemic perspective, learning to see resilience not as a single event or achievement, but as a cycle – a process of prevention, preparation, response, recovery, and assessment, where each stage feeds and strengthens the next.

In dissecting the boundary between cybersecurity and cyber resilience, you will see that prevention is essential, but adaptation and recovery are what truly matter when (not if) defences are breached. The escalation of crisis will be mapped, showing how small disruptions, if mishandled, can grow into existential threats. Through real-life stories like the Sony Pictures incident, you will witness how hesitation, unclear roles, and fragmented communications can amplify harm, and how disciplined leadership can contain it.

The workshop will ground you in the origins of resilience, tracing its evolution from military doctrine – where after-action reviews, mission command, and rapid learning were born – into the realm of business, where scenario planning, cross-functional teams, and continuous improvement now reign. You will analyse your own organization’s structure, examining the strengths and gaps in governance, reporting lines, and crisis team design. The challenge is to ensure that every person knows their role when the stakes are highest, and that the organization can scale its response as needed.

Measurement will become your ally, not your adversary. You will learn how to diagnose your current maturity, select meaningful KPIs, and conduct diagnostic assessments that reveal not only technical gaps, but also weaknesses in culture, decision-making, and leadership. Case studies from shipping, finance, and critical infrastructure will provide templates for turning numbers into narratives and dashboards into decisions.

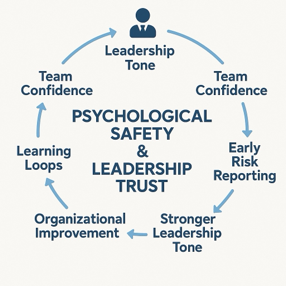

Perhaps most crucially, you will explore the cultural and leadership dimensions of resilience. Here, you will reflect on how tone from the top shapes behaviour on the ground, how psychological safety enables teams to surface problems early, and how learning from failure can be embedded as a source of strength. Through structured self-assessment, you will identify your current state – strengths to be leveraged, blind spots to be addressed. The setting of strategic objectives will move you from insight to action, ensuring that every lesson is translated into concrete priorities and guiding principles.

Figure 02: Psychological Safety & Leadership Trust

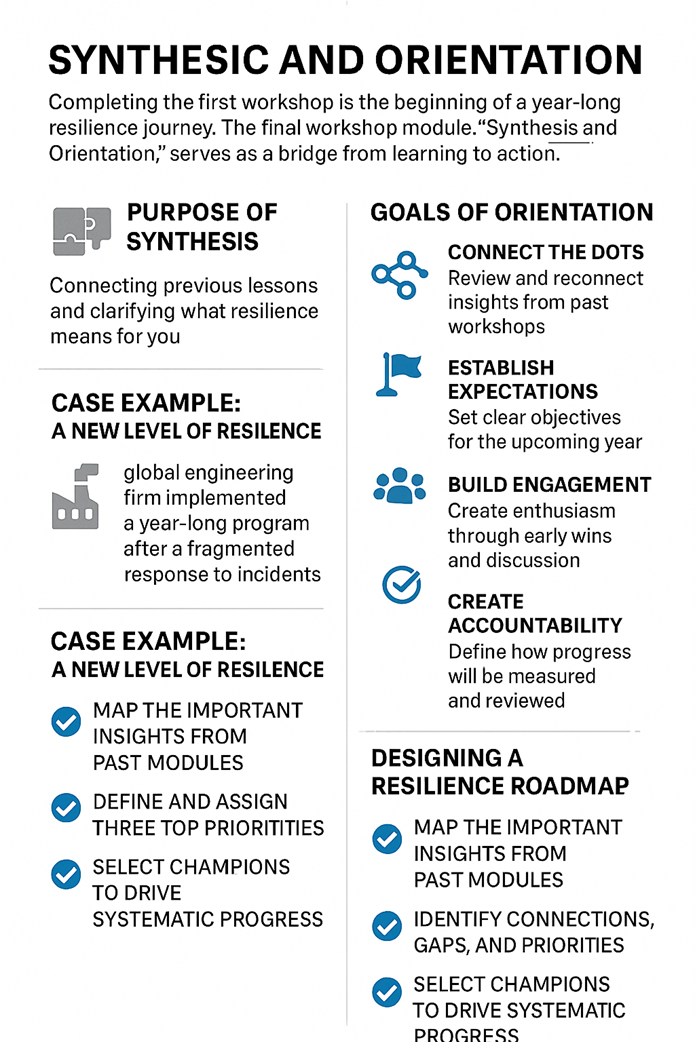

The closing chapter of the workshop weaves these threads together. Through synthesis and orientation, you will connect the dots, see the system as a whole, and set expectations for the month of practical application that follows. The goal is not to emerge with a binder full of notes, but with a living blueprint – a plan for testing, refining, and embedding resilience as you return to your day-to-day responsibilities.

The Month that Follows: From Workshop to Real-World Application

Learning does not stop when the workshop day ends. In fact, the most powerful phase of growth begins as you step back into your real-world environment. Over the next month, you are called to act – not as a passive recipient of training, but as an agent of change.

Each module’s insights will become a set of living experiments. You might revisit your mission statement, using new language to rally your team. Perhaps you will conduct a tabletop exercise, simulating the escalation of a crisis and observing how your structure, communication, and decision-making hold up. You may initiate a diagnostic assessment, discovering not only technical vulnerabilities but also gaps in trust or psychological safety. For some, the work may involve drafting new KPIs, building a resilience dashboard, or mapping out a revised escalation path. For others, it may mean having honest conversations about culture, leadership tone, or the unspoken fears that hold people back from surfacing problems.

What makes this month unique is the expectation that you will return – not just with successes, but with challenges, surprises, and lessons learned. The process is cyclical, not linear. You are encouraged to share, reflect, and adapt in partnership with your peers and facilitators. Over time, this cycle of workshop, application, and review will build not only individual competence, but organizational muscle memory – a reflex for resilience that endures.

What You Will Achieve: Personal, Team, and Organizational Transformation

The benefits of this approach are layered and profound. On a personal level, you will develop a new relationship with uncertainty. The workshop and month of application will invite you to move beyond the instinct to avoid or minimize risk, instead learning to confront it directly, extract its lessons, and transform it into fuel for growth. You will hone your capacity for adaptive leadership, clear communication, and decision-making under pressure – skills that transcend any single role or crisis.

For your team, the journey becomes an opportunity to build trust, alignment, and shared language. As you work through the modules together, silos will begin to dissolve, unspoken assumptions will be surfaced, and a new level of clarity about roles, responsibilities, and escalation will take hold. Teams that learn resilience together discover that they can act with greater unity and effectiveness, even in the face of the unknown.

At the organizational level, you will gain the tools to diagnose your current state, set strategic objectives, and track measurable progress. You will see how resilience becomes a source of competitive advantage – winning the confidence of regulators, investors, and customers, and laying the groundwork for sustained innovation and agility. Perhaps most importantly, you will begin the slow but powerful work of cultural transformation, creating a workplace where learning, transparency, and psychological safety are not aspirations, but daily practices.

A Glimpse into the Future: The Evolving Landscape of Resilience

As you begin this journey, it is worth looking ahead to the forces that will shape the resilience agenda in years to come. The digitalization of business and society will only accelerate, making cyber resilience a top priority for organizations of every kind. Artificial intelligence, automation, and big data will create both new opportunities and new risks. Supply chains will become more complex, and the expectations of stakeholders more demanding. Regulatory regimes will evolve, requiring ever more robust evidence of resilience and continuity planning.

But the core truths will remain. No technology, no matter how advanced, can replace the importance of human judgment, adaptive leadership, and a culture of trust. The organizations that thrive will be those that treat resilience not as a compliance issue, but as a strategic capability-one that is practiced, measured, and renewed, month after month and year after year.

The Philosophy and Methodology Behind the Workshop

This program is built on the conviction that resilience is not an innate trait, but a learned discipline. The workshop experience is immersive, experiential, and reflective. It invites you to grapple with real dilemmas, surface your own assumptions, and challenge routine ways of thinking. Case studies, such as those of Maersk and Sony Pictures, will not be presented as distant stories but as mirrors – opportunities to see your own organization’s vulnerabilities and strengths more clearly.

Figure 03: Workshop Methodology

The methodology emphasizes group learning, cross-functional collaboration, and iterative cycles of action and reflection. You will engage in live simulations, scenario planning, diagnostic assessments, and strategic mapping. Reflection will be balanced by action; every insight is tested against the reality of your own context, and every challenge is viewed as a chance to innovate.

The expectation is that you will bring your whole self to the process – your expertise, your questions, your uncertainties, and your hopes for what your organization can become. The facilitators are not here to deliver answers, but to guide a process of discovery, challenge, and renewal.

Who Should Join the Journey

Resilience is not the exclusive domain of senior leaders or crisis managers. While this workshop is designed for executives, functional heads, risk professionals, and emerging leaders, its greatest impact comes when teams participate together – sharing their diverse perspectives and building collective ownership. Every person, regardless of role, contributes to the organization’s ability to see, decide, act, and recover. The program is designed to be inclusive, fostering a sense of shared mission and mutual accountability.

A Personal Invitation: Stepping Into the Arena

This introduction is more than a roadmap. It is an invitation to step into the arena. Resilience is forged not in theory, but in action – when the heat is on, when plans go awry, when leaders and teams are tested. The first workshop day marks the beginning of your organization’s next chapter. Over the coming month, as you apply and extend what you learn, you will find new strengths, uncover blind spots, and begin to create a culture where resilience is both an expectation and a source of pride.

The road ahead will be challenging. There will be false starts, difficult conversations, and unexpected setbacks. But each of these is an opportunity to grow. As you embark on this journey, remember that resilience is not about never falling, but about rising every time you do-wiser, stronger, and more prepared for whatever comes next.

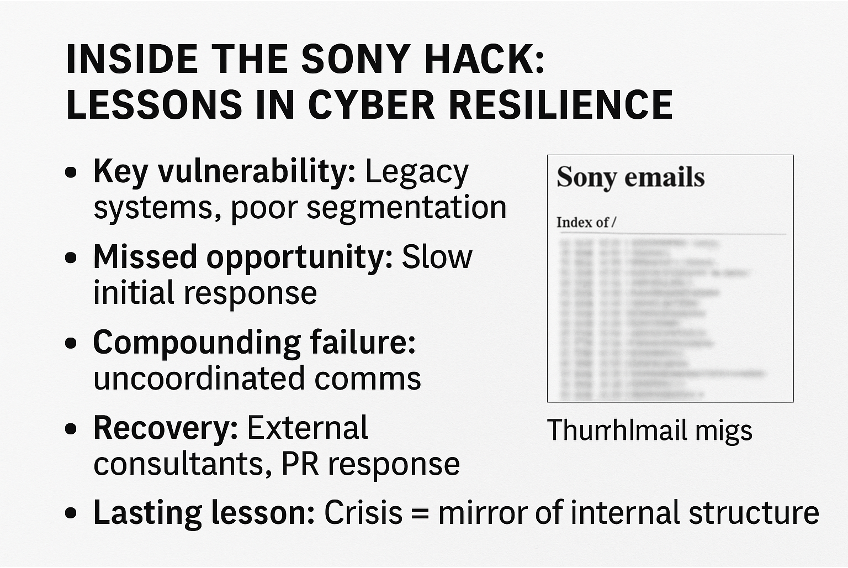

Lessons Learned from Case Studies like the Sony Picture Case will guide you through all workshop modules. The better the transfer to your business the better you will be prepared for the future. The set-up of your company’s internal structure will be key. And that’s where we will shape all the time.

Figure 04: Lessons Learned – e. x. Sony Pictures Hack

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Resilience Defined

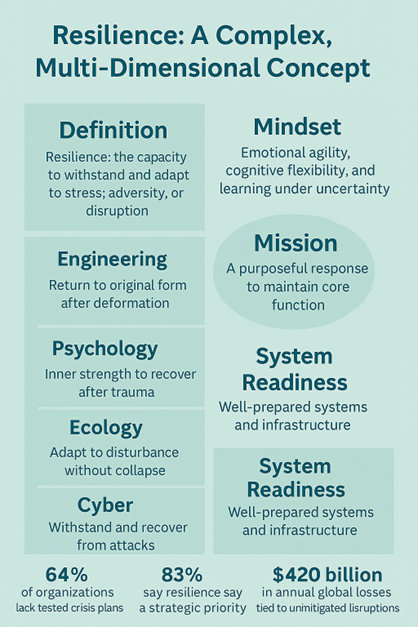

Resilience is the defining capability of organizations that survive and thrive in the modern world. In this foundational chapter, we break down resilience into three inseparable elements: meaning, mindset, and mission. These are not abstract ideals but living forces that shape every decision, every response, and ultimately, every outcome when adversity strikes.

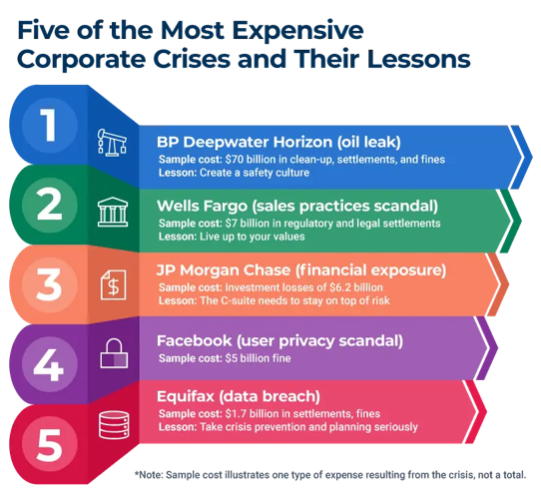

Historical crisis, like in the following infographic show how huge crises can be:

Meaning provides the “why” behind resilience. Organizations with clear meaning understand what truly matters: their core values, their critical assets, and the unique purpose they serve in the market or society. When disruption occurs-be it cyberattack, pandemic, or market collapse-it is meaning that keeps teams focused and motivated. This chapter explores methods to articulate and embed meaning, from leadership communication to value-driven goal setting. Real-world vignettes show how companies with a strong sense of meaning make faster, more effective choices under pressure.

Mindset is the psychological engine of resilience. Drawing on the latest behavioural science, we distinguish between fixed and growth mindsets, exploring how belief systems influence risk-taking, innovation, and learning from failure. Organizations with resilient mindsets foster psychological safety, encourage curiosity, and promote adaptability. In practice, this means not just reacting to crises, but anticipating them, and viewing each setback as a chance to learn and improve. Exercises prompt participants to reflect on their personal and collective mindset, identifying areas where fear of failure or blame culture may hold back resilience.

Mission gives resilience its direction. In a world where threats are unpredictable and constant, mission-driven organizations have a clear “north star” that guides action even when the future is uncertain. This mission is operationalized through strategy, policy, and culture, aligning every layer of the organization toward shared, actionable goals. Through interactive scenarios, participants practice translating mission statements into practical priorities during simulated crises.

Throughout the chapter, case studies like the Sony Pictures cyberattack provide powerful evidence. Sony’s experience illustrated how unclear mission and fragmented meaning led to hesitation, confusion, and increased impact. In contrast, organizations with unified meaning, resilient mindsets, and shared mission managed to contain crises more quickly and use adversity as a catalyst for renewal.

By the end, participants will have a working definition of resilience that is personal, practical, and aligned with their organization’s unique context. This definition will be referenced and deepened throughout the entire workshop journey.

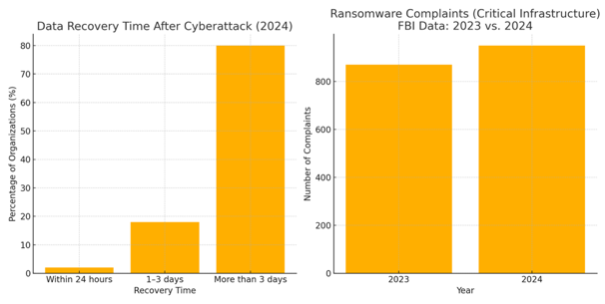

The threat of ransomware continues to escalate, particularly for operators of critical infrastructure. According to the FBI, 2024 saw a 9% increase in ransomware complaints affecting critical infrastructure sectors in the U.S. Nearly half of all ransomware reports submitted to the FBI were linked to this segment, underlining both the growing threat and the urgent need for advanced crisis and resilience planning in essential industries.

Chapter 2: Resilience Cycle

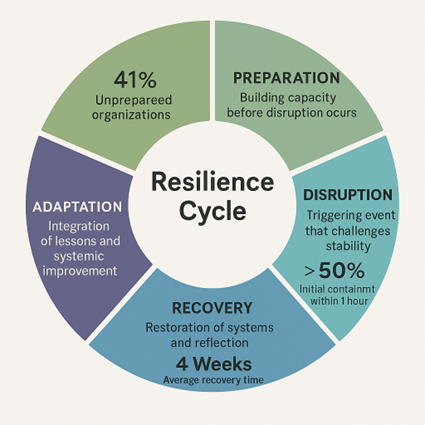

Resilience is not a one-time achievement or a static state. It is an ongoing cycle-a living system that is embedded into the DNA of resilient organizations. This chapter introduces the Resilience Cycle, which underpins every subsequent part of the workshop. Participants learn to see resilience not as a linear process, but as a series of interconnected phases that repeat and reinforce one another.

The Resilience Cycle is typically represented by five interlocking stages: Prevention, Preparation, Response, Recovery, and Assessment. Each stage is distinct, but their value lies in their integration and feedback loops.

Prevention focuses on early detection and risk mitigation. It’s about building systems, processes, and cultures that are always scanning the horizon for emerging threats. Participants analyse how robust risk sensing, regular audits, and clear communication of “near misses” can prevent minor disruptions from spiralling.

Preparation is about readiness. This includes crisis simulation exercises, training, and establishing protocols so that when the alarm sounds, everyone knows their role. Practical sessions guide participants through scenario planning and resource mapping, showing how gaps in preparation create chaos in later stages.

Response is the phase most visible during a crisis. Here, the quality of communication, decision-making, and leadership are stress-tested. Through live crisis simulations, participants practice rapid escalation, stakeholder management, and adaptive leadership.

Recovery addresses how to restore normal operations, reputations, and stakeholder confidence. Case studies reveal why organizations with documented recovery playbooks and pre-defined recovery teams return to stability faster and with less collateral damage.

Assessment is the final – but never-ending – stage. After-action reviews, debriefs, and lessons-learned sessions ensure that every crisis, whether large or small, becomes an opportunity for organizational growth. Assessment closes the feedback loop, driving improvements in prevention, preparation, and overall culture.

This systemic perspective is made real through the mapping of recent global crises – including Maersk’s NotPetya response and the COVID-19 pandemic – onto the Resilience Cycle. Interactive group work encourages participants to diagnose where their own organizations excel or falter at each stage.

Participants leave this chapter with a practical, cyclical model for embedding resilience across teams, processes, and leadership structures – ready to be adapted to their unique context.

Chapter 3: Cybersecurity vs. Cyber Resilience

Many organizations mistakenly equate cybersecurity with cyber resilience. This chapter unpacks the crucial difference and makes a compelling case for why every modern business must pursue both but never confuse the two.

Cybersecurity is focused on prevention – deploying controls, technologies, and policies to defend against unauthorized access, malware, ransomware, data theft, and other digital threats. It is necessary, but as every expert knows, not sufficient. No cybersecurity program, no matter how well funded or technically advanced, can guarantee 100% protection. Breaches are a matter of “when,” not “if.”

Cyber Resilience, by contrast, is the organization’s capacity to adapt, recover, and learn when those defences are inevitably breached. This includes the ability to restore critical operations, communicate transparently with stakeholders, maintain trust, and prevent a single incident from causing cascading harm.

Through detailed case studies – Sony Pictures, Maersk, and others – participants see that cybersecurity failures can become catastrophic only when resilience is weak. Sony’s breach showed that technical defences were only part of the battle; confusion in crisis communications and lack of recovery plans compounded the impact. Maersk’s swift recovery after NotPetya highlighted the payoff of resilience investments: rapid restoration, strong backup protocols, and empowered crisis teams.

Workshops challenge participants to shift from a fortress mentality (“How do we keep them out?”) to a survival and adaptation mindset (“How do we keep running, even when they get in?”). Exercises include mapping current cybersecurity practices, stress-testing response plans, and identifying single points of failure.

By chapter’s end, the distinction is clear: Cybersecurity is about risk reduction; cyber resilience is about risk survival and recovery. Both are essential for the digital era, and together they form the backbone of a robust organizational strategy.

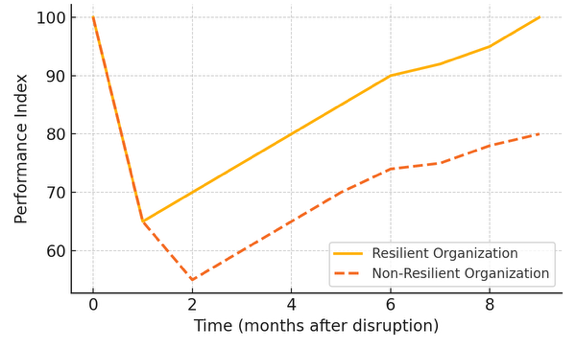

The infographic below titled “Organizational Performance & Recovery After Adversity” visually illustrates how resilient organizations recover more rapidly and completely after a major disruption compared to non-resilient organizations. Both groups experience a sharp initial drop in performance following a crisis, but the resilient organization (represented by the solid orange line) demonstrates a steady and robust recovery, quickly returning to pre-crisis performance levels. In contrast, the non-resilient organization (shown by the dashed orange line) recovers much more slowly and never fully regains its original performance, highlighting the lasting impact of insufficient resilience. This visualization underscores the core value of investing in organizational resilience as a means to ensure faster, more effective recovery from unexpected challenges.

Chapter 4: Anatomy of a Crisis

One of the most vivid and instructive cases that will accompany us throughout this workshop is the cyberattack on Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014. This case, which we will analyse in detail during the module on the anatomy of a crisis, embodies many of the themes explored across the twelve chapters-from the nature of organizational resilience and the pitfalls of siloed crisis response to the imperative for clear leadership, strategic communications, and measurable improvement.

The Sony Pictures breach was more than just a headline-grabbing event; it was a defining moment in modern resilience thinking. The attack unfolded rapidly, exposing not only technical vulnerabilities but also deeper organizational weaknesses: unclear roles, fragmented escalation, and a lack of rehearsed crisis management routines. As the breach escalated, it became painfully clear how critical it is for organizations to move beyond traditional cybersecurity and develop true cyber resilience. Sony’s journey – from initial shock and confusion to public scrutiny and, ultimately, to hard-earned recovery – mirrors the resilience cycle we will study. The lessons learned from this crisis highlight the interconnectedness of governance, culture, leadership, and strategic foresight.

By integrating the Sony Pictures case study, this workshop invites participants to move beyond theory and abstraction, engaging directly with the decisions, dilemmas, and consequences faced in high-stakes real-world crises. Through group analysis, scenario exercises, and structured reflection, you will have the opportunity to see how the principles of resilience apply under pressure, and to translate these lessons into actionable strategies for your own organization. In doing so, we not only learn from the past but equip ourselves for the challenges ahead, making resilience a lived, practiced capability – not just an aspiration.

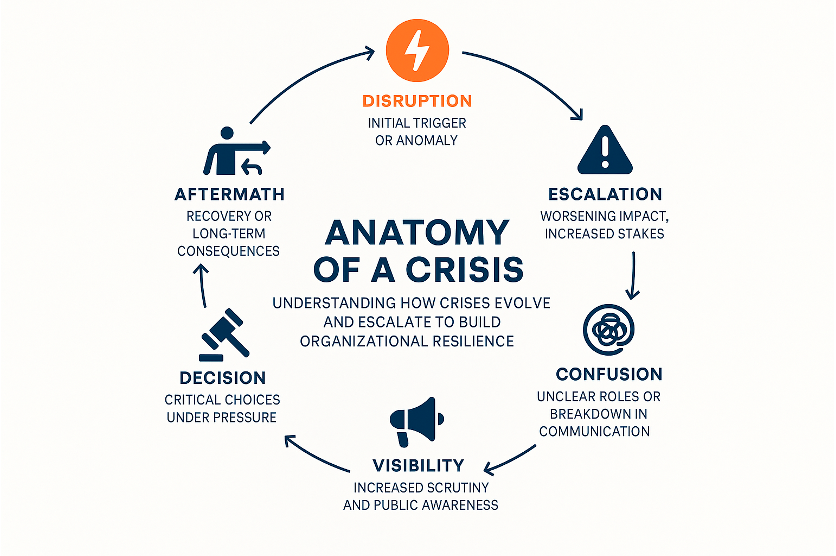

Course Manual 4 explores the dynamic and often misunderstood nature of crises. The central premise is that a crisis rarely appears fully formed; it escalates through recognizable stages that must be understood to build real organizational resilience. Far from being isolated events, crises are evolving processes shaped by internal responses just as much as external pressures. The ability to detect early signals, act decisively, and maintain coordinated leadership during high-stress moments determines whether a disruption becomes a disaster-or an opportunity for learning and growth.

The manual begins by emphasizing that crisis is a process, not a moment. A minor disruption-be it a technical glitch, suspicious behaviour, or system anomaly-can rapidly evolve into a full-blown organizational emergency. This evolution is governed by escalation: the step-by-step intensification of impact, visibility, and emotional strain. Crucially, this escalation is not just about what happens externally, but also how organizations respond internally. Failure to recognize early signals, delayed decisions, or unclear roles can allow a minor issue to spiral into a major crisis.

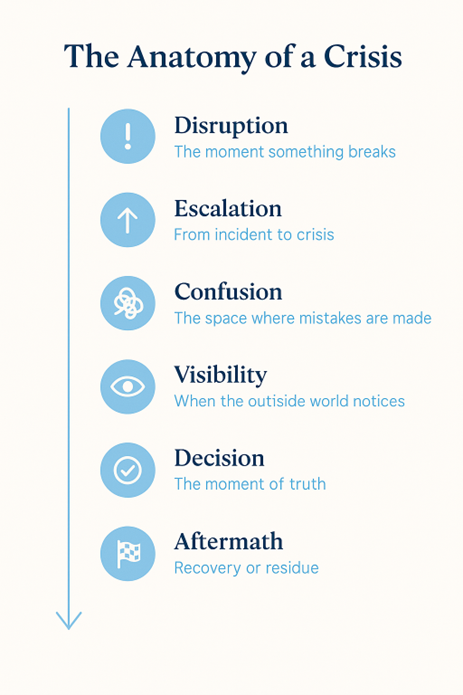

Understanding the anatomy of a crisis means identifying the phases that most crises follow. The manual outlines six key stages:

Disruption: This is the initial trigger-the moment when something breaks or behaves unexpectedly. Often, early signs are subtle or ambiguous. A delay in response, uncertainty about the severity, or miscommunication can turn what could have been a manageable incident into a much larger problem. Resilient organizations take disruption seriously from the outset-investigating and escalating early without overreacting.

Escalation: If the disruption is not addressed properly, the situation worsens. Systems degrade further, stakeholders are impacted, and what began as a technical or operational problem becomes a strategic and reputational crisis. During escalation, responsibility expands. More leaders, departments, and external actors become involved. The crisis grows in scope, speed, and stakes-requiring a shift from tactical problem-solving to strategic crisis management.

Confusion: As pressure mounts, communication can break down. Roles become unclear, assumptions proliferate, and emotional responses such as fear or blame complicate decision-making. This phase is where many avoidable mistakes happen-not from incompetence, but from a lack of preparation or psychological safety. Strong leadership at this point is not about having the right answers, but about creating clarity, calm, and cohesion. Communication must be structured and consistent.

Visibility: Once the crisis becomes public-whether through media coverage, customer complaints, or regulatory scrutiny-the organization enters a new arena. Now, how it responds is just as important as what happened. Visibility magnifies impact and attracts attention. Leadership must act with transparency and professionalism, ensuring that public communications reflect integrity and control. Legal and public relations teams often step in here to help frame the response.

Decision: Every crisis includes key decision points-moments where leaders must act boldly, under pressure, and with limited information. These decisions may involve disclosure, shutdowns, or public acknowledgments. What matters is that decision-making authority is clear and supported by guiding principles. Crisis-ready organizations prepare in advance by clarifying who decides what, under which circumstances, and according to what values.

Aftermath: Once the immediate crisis passes, the organization must transition from response to recovery. This is the moment for learning, reflection, and change. Without intentional effort, organizations either forget (losing valuable lessons) or freeze (trapped by fear of recurrence). True resilience is built in this phase-by examining vulnerabilities, honoring those who stepped up, and embedding lessons into new protocols and culture.

The manual’s deeper insight is that crisis escalation is a pattern-not a surprise. While no two crises are identical, most follow similar trajectories. Recognizing this allows organizations to prepare in advance, act earlier, and avoid the most damaging missteps. The emphasis is on developing a shared language for crisis stages, practicing through simulations, and ensuring that leadership structures can flex under pressure.

A real-world case study-the 2014 Sony Pictures Entertainment hack-illustrates these principles vividly. The attack, perpetrated by a nation-state actor, escalated over weeks. Early anomalies were missed, communication was fragmented, and response decisions lagged behind the speed of the threat. As data was exfiltrated and later published, Sony faced not just technical shutdowns, but reputational harm, employee distress, and geopolitical consequences. The company’s response became a case study in delayed recognition, leadership strain, and public fallout.

An additional fictional case study, “Friday Afternoon,” presents a more typical corporate crisis. A minor incident-unauthorized access to financial records-is ignored over the weekend, only to explode into a reputational and technical nightmare by the following Friday. The point is clear: escalation happens not only because of threat actors, but because of delayed action, unclear roles, and siloed thinking.

In conclusion, Course Manual 4 reframes crisis management not as fire-fighting, but as a leadership discipline rooted in pattern recognition, role clarity, and timely, values-based decisions. It is not about avoiding all disruptions, but about knowing what to do when disruptions come. Organizations that train for crisis escalation, foster open communication, and learn from the past are not just reactive-they’re resilient.

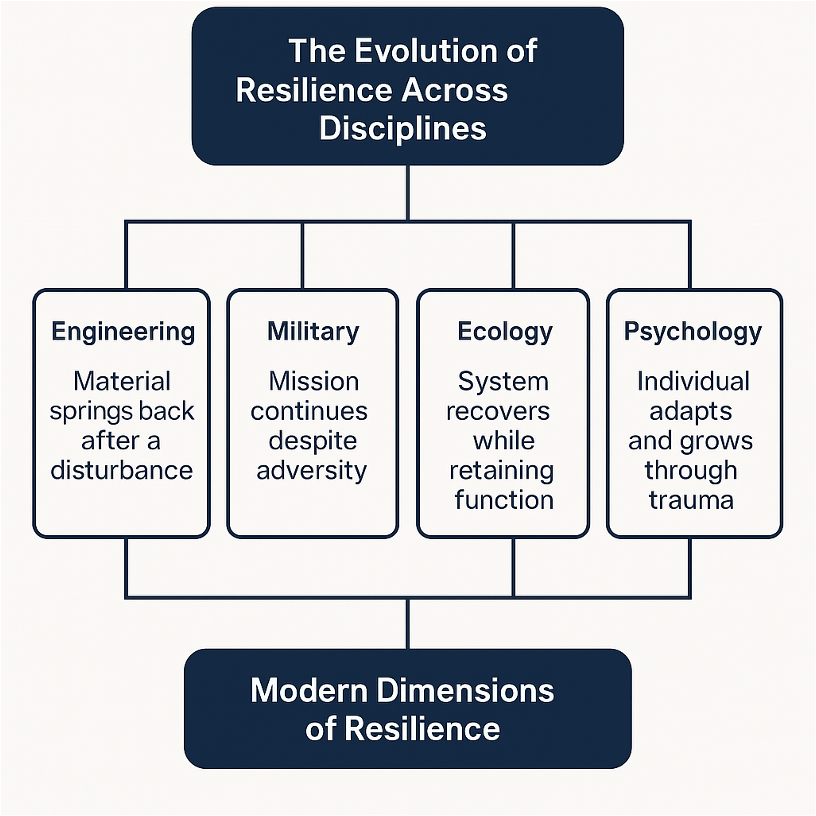

Chapter 5: Resilience Evolution

Resilience is more than a buzzword. It has become one of the most referenced yet misunderstood terms in modern organizational discourse. Governments pledge to build it, consultants market it, executives cite it, and entire industries claim to need more of it. But while the term is ubiquitous, its depth is often lost in metaphor. Too often, it is reduced to vague ideas of “bouncing back” or “staying strong.” This course manual restores meaning to resilience by tracing its multidisciplinary roots, historical evolution, and current strategic importance in a world defined by volatility, disruption, and interconnected risks.

At its essence, resilience is not simply an emotional state or motivational slogan. It is a structural and functional capability-an organization’s ability to absorb shocks, maintain core functions, and adapt under stress. The manual starts by identifying the origins of the word, from the Latin resilire, meaning to rebound or spring back. In early physics and engineering, this referred to materials that could absorb energy and return to their shape. The steel rod that bends but doesn’t break; the suspension bridge that flexes in a storm. This logic of endurance through flexibility is the conceptual foundation for all later understandings of resilience.

However, as systems became more complex and uncertainty more pervasive, resilience evolved from a physical property to a systems principle. One of the first major sectors to embrace this shift was the military. In the fog of war, nothing goes to plan. Military strategists realized that survivability hinged not on avoiding disruption, but on continuing the mission despite it. The modern doctrines of mission command, decentralized leadership, scenario-based planning, and rapid improvisation all stem from this understanding. Resilience, in the military context, was about redundancy, adaptability, and psychological readiness-not control, but continuity under chaos.

This military mindset later influenced national emergency management systems, shaping how countries prepare for crises such as terrorism, natural disasters, or cyberattacks. But parallel to this, another lineage emerged: ecological resilience. In 1973, Canadian ecologist C.S. Holling redefined resilience not as resistance to change, but as a system’s ability to reorganize and recover without losing its core function or identity. In ecosystems, disruption is natural. Forests burn, rivers flood, populations decline. But resilient systems adapt-they change form while preserving structure. This perspective deeply influenced urban planning, disaster risk reduction, and climate adaptation.

Cities, like ecosystems, are systems under pressure. They require resilience to withstand infrastructure failure, extreme weather, social unrest, and economic shocks. Urban resilience planning involves diversification of energy grids, decentralization of transport networks, cross-functional governance, and community cohesion. The shift in thinking-from trying to prevent all disruptions to building systems that adapt and bounce forward-is a hallmark of the ecological approach to resilience.

Meanwhile, psychology brought resilience into the realm of the individual. Studying trauma survivors, childhood development, and mental health, researchers found that some individuals not only survive adversity but grow from it. Resilience here was not innate toughness, but the ability to find meaning, maintain agency, regulate emotion, and access support. Critically, resilience was not seen as a fixed trait-it was a process that could be cultivated. This insight changed leadership development, employee wellbeing programs, and team performance models across sectors.

By the early 2000s, resilience had arrived in the corporate world through risk management and cybersecurity. As businesses grew more dependent on digital systems, it became clear that technical defences alone were insufficient. Cyberattacks, data breaches, system failures, and insider threats exposed organizations to risks that couldn’t always be prevented. This gave rise to cyber resilience-the capability not just to stop threats, but to detect them early, respond effectively, and recover quickly. Firewalls became necessary but not sufficient. Crisis teams, tested contingency plans, and recovery protocols became essential.

This shift marked a broader transformation. Resilience became a strategic differentiator. Companies that demonstrated resilience were better able to maintain operations, retain customer trust, and protect reputations during disruptions. Boards began asking different questions-not just “Are we secure?” but “Are we ready?” Resilience moved from the domain of risk officers to the C-suite. Annual reports began referencing resilience as a core pillar of ESG strategy. Investors and regulators began assessing it. Executive KPIs began to reflect it.

Consulting firms and standards bodies responded. They developed resilience maturity models, diagnostic assessments, and capability frameworks. These measured not just technological redundancy, but decision-making agility, leadership trust, cultural preparedness, and cross-silo collaboration. A resilient organization, by these models, wasn’t just one that could recover quickly-it was one that could adapt structurally and emerge stronger.

Across every field explored-military, ecology, psychology, cybersecurity, and corporate strategy-the common thread is adaptive capacity. Resilience is not about returning to “normal.” It is about evolving toward a new equilibrium, one that incorporates lessons, strengthens foundations, and improves future readiness. Resilience is not static. It is dynamic. It requires a mindset of continuous learning and a willingness to lead through uncertainty.

The manual also emphasizes that resilience is both a leadership principle and a cultural attribute. Resilient organizations do not centralize resilience in one department; they embed it across the enterprise. Leaders model calm under pressure, enable rapid decision-making, and foster psychological safety. Teams train for disruption, debrief failures, and align around shared values. The culture prioritizes honesty over blame, learning over perfection, and transparency over control.

A compelling case study reinforces these principles. During a massive ransomware attack that crippled national infrastructure, one regional hospital stood out. While others went offline, this hospital maintained operations-because it had invested in resilience ahead of time. It had conducted cross-functional simulations, clarified escalation paths, tested backups, and prepared staff. When crisis hit, there was no confusion. The hospital functioned because resilience was not an abstract goal-it was a practiced reality.

To help participants apply the lessons of the manual, the included exercise “Mapping Your Resilience Lineage” invites teams to trace their organization’s response to past disruptions. Through timeline-building, group discussion, and reflective analysis, they assess whether past crises led to growth or stagnation. This exercise challenges participants to confront hard truths about their organization’s culture: Do they prepare, improvise, or avoid? What legacy of resilience do they want to build?

In conclusion, resilience is not a trend. It is a necessity. It is not something to be acquired in response to crisis, but something that must be cultivated in advance. In an age of polycrisis-where cyber threats, climate events, political unrest, and economic shocks converge-resilience is what separates decline from durability. It is the connective tissue of future-ready organizations: a mindset, a practice, and a promise to continue-not in spite of disruption, but because of it.

Chapter 6: Organizational Structure

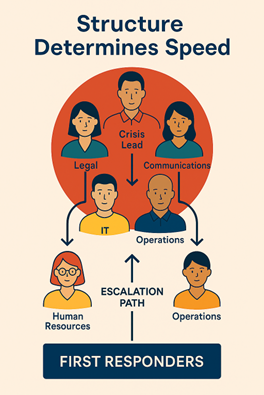

When crisis strikes, it’s not usually the lack of resources that causes the greatest damage-it’s the absence of clarity. Whether the trigger is a cyber breach, natural disaster, operational failure, or reputational threat, the true risk lies in the fog that follows: confusion over roles, responsibilities, authority, and timing. This manual establishes that the most resilient organizations are not the ones with the most resources, but the ones with the clearest structures-living systems of coordination, decision-making, and communication built long before a crisis hits.

The core argument is simple: structure is the skeleton of resilience. It determines how people respond, how decisions are made, and how quickly an organization can pivot under pressure. Good structure is not a set of charts or policies. It is a dynamic architecture of relationships, behaviours, and responsibilities that comes alive during disruption. It is elastic, not rigid-capable of stretching without snapping, adapting without losing coherence.

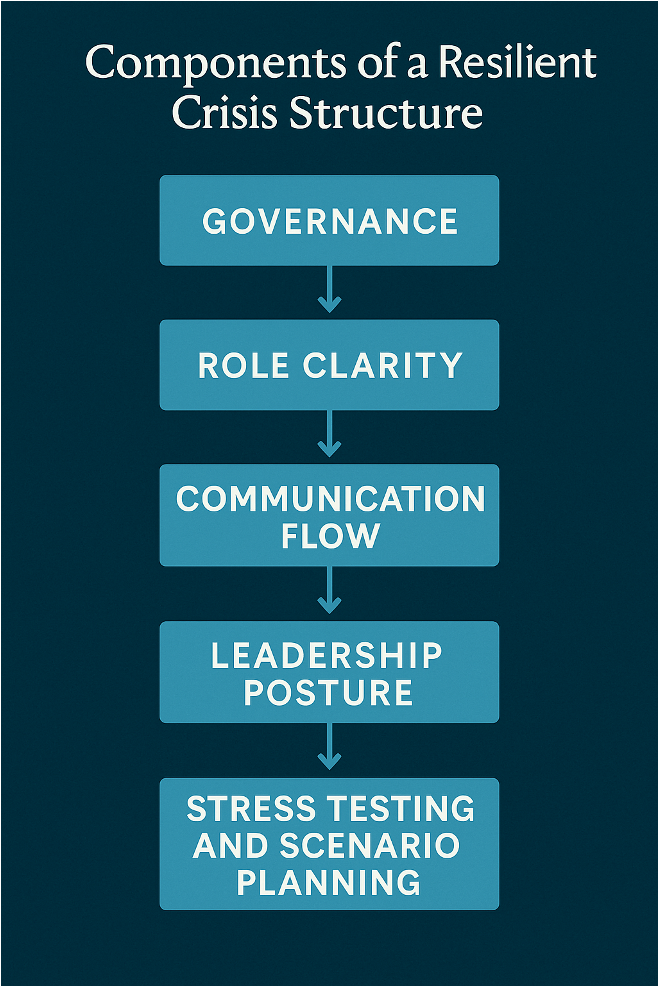

In everyday operations, structure may be invisible. But under stress, its quality becomes immediately evident. Weak structures collapse under pressure; resilient ones guide the organization through chaos. This manual outlines the components of crisis-ready structure: governance, role clarity, communication flow, and leadership posture.

Governance: The Framework for Decision-Making

Effective governance is the foundation of a functioning crisis structure. It defines how decisions are made, who is accountable, and how authority flows under pressure. In crisis situations, traditional governance structures are often too slow or too centralized to respond adequately. That’s why high-reliability organizations create alternative structures, such as:

• Crisis Management Teams (CMTs)

• Tactical Response Cells

• Emergency Operations Centers (EOCs)

• Resilience Hubs

These bodies operate on faster cycles, with flatter hierarchies and delegated authority. They don’t replace standard governance but form a parallel command structure designed for speed, coordination, and real-time responsiveness.

Governance in resilient organizations is not only functional-it’s also ethical. It ensures that decisions are accountable, transparent, and timely. The goal is not perfection but integrity under pressure.

Role Clarity: Knowing Who Does What

One of the most common failure points in crisis is the absence of role clarity. Organizations often assume people know what to do because their names are on a plan. But in practice, roles may be undefined, alternates may be untrained, and decision rights may be ambiguous.

Resilient organizations address this proactively. They rehearse roles, rotate responsibilities, and clarify expectations before a crisis begins. Every person involved in crisis response should be able to answer:

• What is my task?

• What decisions can I make?

• Who do I report to?

• Who do I support-and who supports me?

In matrixed organizations, the situation is even more complex. People report to multiple leaders, sit on overlapping teams, and carry dual roles. In a crisis, such ambiguity can paralyze action. That’s why temporary, simplified authority lines are often enacted during disruption. For example, an HR director may temporarily report to a unified crisis cell, bypassing traditional reporting for speed and focus.

Communication Flow: Speed, Looping, Redundancy

Communication is the lifeblood of crisis management, and structure determines how that blood flows. Effective reporting lines are short, looped, and agile. They support:

• Upward escalation

• Lateral coordination

• Downward command

This ensures that insights from the field reach decision-makers quickly-and that instructions are returned clearly and promptly. Tools such as dashboards, chat apps, and email alerts help, but resilient organizations don’t rely solely on technology. They stress-test human behaviours behind tools, ensuring backups exist if systems fail.

For instance, printed contact trees, pre-verified escalation paths, and role cards become essential when digital systems go offline-during holidays, night shifts, or widespread outages.

Rhythm and Predictability

In the chaos of crisis, predictable rhythm becomes an anchor. Resilient crisis teams work in time blocks. They may hold check-ins every 30 minutes, issue stakeholder updates every 2 hours, and conduct coordination meetings hourly. These rituals build focus, prevent drift, and create psychological safety. A consistent rhythm supports momentum and limits stress.

Leadership: Posture and Distribution

Leadership is the center of crisis structure-but not in a command-and-control sense. Resilient leaders exhibit calm visibility, compassionate decisiveness, and inclusive engagement. They step forward to set tone but not to micromanage. They empower others, ask questions, listen deeply, and model clarity. Most importantly, they absorb stress without passing it down.

But crisis leadership is not a solo performance. It must be distributed. No one leader can manage every decision or relationship in a large-scale event. Therefore, authority must be delegated. That requires trust, training, and standardization. A great structure allows good leadership to echo across departments, locations, and time zones.

Stress Testing and Scenario Planning

No structure, no matter how well-designed, is crisis-ready if it has never been tested. That’s why scenario planning, tabletop exercises, and “red team” simulations are critical. These practices expose weaknesses, reveal assumptions, and show how escalation actually happens – not how it’s imagined to happen.

Exercises should go beyond checklist rehearsals. They must be immersive, high-pressure, and multidisciplinary. Simulations reveal where information gets stuck, where decisions bottleneck, and where accountability is missing.

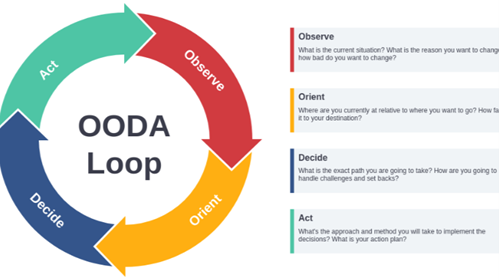

Decision Frameworks: FORDEC, OODA, and More

Crisis structure also includes decision-making frameworks. Tools like the FORDEC model (Facts, Options, Risks, Decision, Execution, Check) or the OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) help reduce cognitive overload under stress. They provide clarity without rigidity, guiding action based on principles, not panic.

These frameworks empower teams to make good decisions in real time-aligning their actions with strategic goals and organizational values, even when information is incomplete.

Brand and External Interfaces

Structure protects more than operations-it protects reputation. How an organization appears during a crisis depends on the consistency, speed, and clarity of its communication. Delayed updates appear evasive. Contradictory messages erode trust. But when communication is aligned, timely, and fact-based, the organization projects confidence-even amid uncertainty.

This requires structured external interfaces. Who speaks to the media? Who manages regulators, partners, vendors? These roles must be trained and integrated-not invented mid-crisis. A strong internal structure must be mirrored externally.

Emotional Stability and Morale

Crises are emotional experiences. Teams face fear, confusion, and burnout. Ambiguity is the enemy of morale. Clear structure gives people a place to stand, a role to play, and a path forward. It reduces anxiety and channels energy productively.

For customer-facing teams and frontline responders-often the most exposed and least empowered-structure is protection. It shields not from risk, but from unnecessary confusion. It shows: “You are not alone. You are part of a system that knows how to act.”

Evolution and Continuous Improvement

Finally, structure must evolve. As teams change, technologies shift, and new risks emerge, structure must be reassessed. Every crisis offers an opportunity to tune the system. After-action reviews should focus not only on what went wrong, but on how structure performed: Was escalation timely? Were roles clear? Did governance adapt?

Culture plays a key role here. Organizations that embrace structural learning-that reward openness, own mistakes, and celebrate improvement-embed resilience not just in process, but in identity.

Case Study: The Power Grid Blackout

A heatwave led to cascading failures in Europe’s power grid. In one region, delayed communication and unclear leadership exacerbated the outage. Emergency plans existed, but no one activated them. Local teams worked at cross-purposes. The result: reputational and operational damage.

Elsewhere, a northern utility had rehearsed its structure. Within 10 minutes, its crisis cell activated. Roles were clear. Communications were fast and aligned. Stakeholders were briefed every hour. Power was restored methodically within 24 hours. The difference wasn’t budget-it was structure.

Conclusion

Resilience begins not in the moment of disruption, but in the structures built long before it. Crisis-ready organizations don’t improvise roles or governance under stress-they rehearse them. They don’t chase clarity in chaos-they embed it in culture. Structure is not bureaucracy. It is freedom-the freedom to act with speed, coordination, and confidence when it matters most.

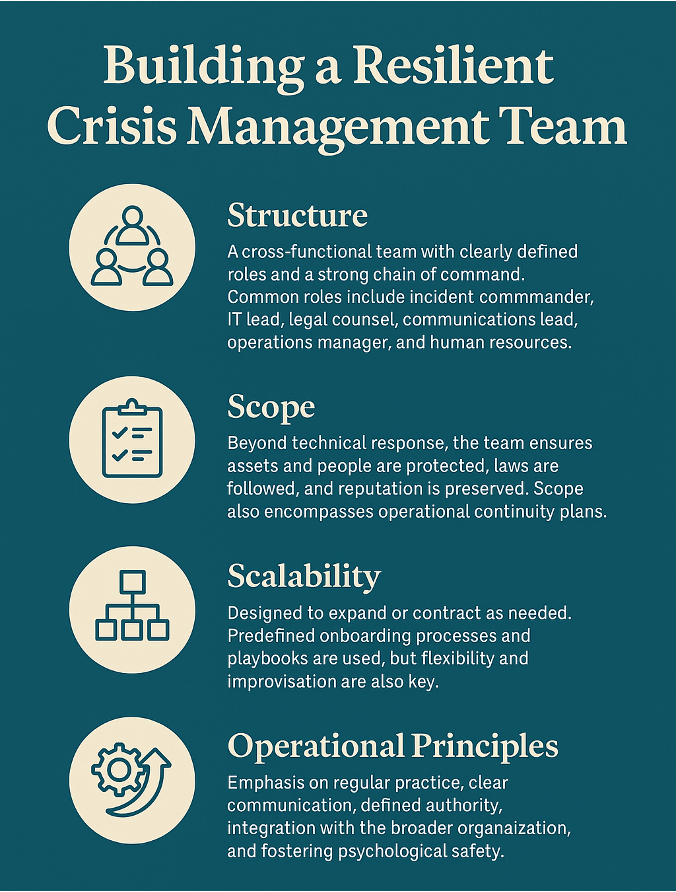

Chapter 7: Resilient Command Model

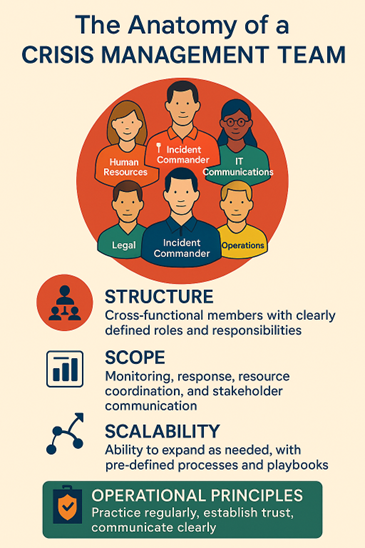

Resilience in crisis doesn’t happen by chance-it’s the product of intentional design. It stems from deliberate planning, practiced coordination, and a shared commitment to act decisively under pressure. At the center of this resilience lies the Crisis Management Team (CMT)-a dedicated group entrusted with leading an organization through disruption, stabilizing operations, protecting critical assets, and preserving reputation. The effectiveness of this team can determine whether a crisis is contained or escalates into catastrophe.

A high-performing CMT is far more than a technical task force. It embodies an organization’s collective ability to respond with clarity, speed, and control when the unexpected strikes. Its success depends on three interdependent elements: structure, scope, and scalability.

Structure: Roles and Responsibilities

A resilient CMT is cross-functional, drawing members from diverse parts of the organization. Core roles typically include:

• Incident Commander – the overall decision-maker

• IT Lead – managing technical containment and recovery

• Legal Counsel – ensuring regulatory compliance

• Communications Lead – handling internal and external messaging

• Operations Lead – overseeing business continuity

• Human Resources – protecting employee wellbeing

Additional specialists – such as cybersecurity experts or PR consultants, depending on the crisis

For a CMT to function well, role clarity is non-negotiable. Each member must understand their responsibilities and authority-including who acts as backup if they’re unavailable. Ambiguity in a crisis creates delays, conflicting decisions, or even complete paralysis. A pre-established crisis plan provides the foundation, but flexibility is crucial: the CMT must adapt as the situation evolves.

Scope: From Detection to Recovery

The mandate of the CMT extends far beyond resolving a technical problem. It is responsible for:

• Detecting incidents early

• Assessing severity and potential impact

• Activating response protocols

• Managing internal coordination

• Communicating with stakeholders

• Making escalation decisions

• Ensuring service continuity and recovery

The team must decide which functions must stay live, what can be paused, and how to allocate scarce resources during disruption. A resilient CMT balances urgency with discipline-taking decisive action while avoiding panic or misinformation.

Scalability: Adapting to Crisis Size

Not every disruption requires a full-scale response. A well-designed CMT must be scalable, able to expand or contract based on the scope and intensity of the incident. Smaller incidents may be handled by a lean core team, while larger events may require broader participation-including external advisors and additional functional leaders.

To enable this flexibility, organizations often develop scenario-based playbooks and tiered response models. These define clear thresholds for activating different levels of response-from department-level interventions (Tier 1) to executive-led crisis coordination (Tier 3). Scalability also ensures that the team doesn’t burn out during prolonged events by shifting between tactical operations, strategic planning, and recovery mode.

Operational Foundations: Rhythm, Authority, and Culture

A strong CMT operates on clear rhythms and routines. Cadence matters: regular huddles every 30 minutes, structured updates every 90, and full team alignments every few hours help maintain momentum and focus. The CMT leader acts as an orchestrator-ensuring everyone is heard, decisions are tracked, and outcomes are aligned.

But leadership is not just about presence-it’s about behaviour. Effective crisis leaders remain calm, communicative, and confident. They absorb pressure without passing it down. They model integrity and build trust, especially when decisions must be made without perfect information.

The culture of the CMT is equally important. Psychological safety allows team members to raise concerns, challenge assumptions, and admit uncertainty. A blame-based culture weakens resilience; a learning-based one strengthens it. Crisis exposes organizational character-how well a team collaborates under pressure often determines whether a disruption becomes a failure or a success story.

Integration and Communication

CMTs don’t operate in isolation. They must be deeply integrated into broader governance structures. That means clear escalation paths to executive leadership, strong links to business continuity, and coordination with departments like IT, Legal, HR, and Risk.

Communication is critical. The CMT must control messaging internally and externally-ensuring that employees, partners, regulators, and the public hear consistent, timely, and credible information. Assigning trained spokespersons, preparing message templates in advance, and securing communication channels are best practices.

Interfaces with the outside world are also vital. The team must know how to engage law enforcement, work with regulatory agencies, update clients, and manage the media. Delays here are costly-public trust can evaporate if organizations appear confused, evasive, or unprepared.

Documentation and Drills

Even the best-designed CMT must be tested. Tabletop exercises and full-scale simulations develop “muscle memory,” uncover hidden gaps, and refine response protocols. These exercises also ensure that playbooks-brief, visual guides for specific crisis types-remain current and usable.

Good documentation is fast, flexible, and focused. Every team member should know exactly where to find activation checklists, contact directories, escalation matrices, and communication templates-within seconds, not minutes.

Lessons from the Field

The manual concludes with real-world examples. A fintech startup, following a minor data breach, built its CMT from scratch-clarifying roles, training members, and rehearsing responses. When a major incident occurred months later, the team responded smoothly. Another case, involving a ransomware attack on a water utility, demonstrated the power of preparation. Within 30 minutes of detection, the crisis team was activated, coordinated, and communicating-containing the impact and preserving trust.

Conclusion

In crisis, time is unforgiving. Delay multiplies damage. Confusion fractures credibility. The organizations that thrive are those with a clear, practiced, and trusted Crisis Management Team. Not a symbolic group, but a functional command structure-built in calm, tested in tension, and trusted when it matters most.

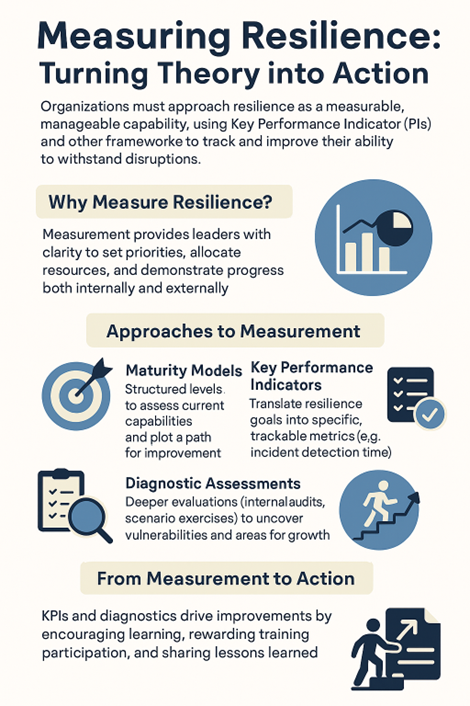

Chapter 8: Measuring Resilience

In an era of escalating digital threats, stakeholder scrutiny, and regulatory complexity, organizational resilience can no longer remain an abstract ideal. It must become a measurable, trackable, and improvable capability-treated with the same strategic rigor as financial performance or operational efficiency. Resilience is not simply a mindset; it is a structured, data-informed practice that must be embedded into the daily management of the organization.

At the core of modern resilience management lies the use of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). These indicators translate broad visions and strategic goals into tangible, measurable outcomes. However, KPIs are often misunderstood or misapplied-reduced to superficial metrics on dashboards that fail to reflect the deeper realities of organizational preparedness and adaptability. To unlock their full value, leaders must understand not just how to track performance, but how to design meaningful measurements that reflect the true state of resilience.

The roots of effective measurement lie in the philosophy of “management by objectives,” a concept popularized by Peter Drucker. He emphasized the importance of clear, shared goals and collaborative engagement across the organization. Applied to resilience, this approach ensures that the ability to absorb and recover from shocks is not accidental, but deliberate and embedded across functions and teams. It shifts responsibility for resilience from a single team to the entire organization.

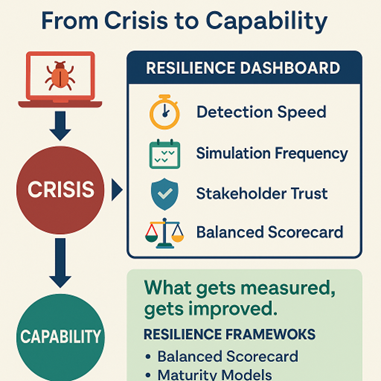

Effective KPIs act as organizational compasses, helping teams focus on what matters most. Unlike vanity metrics that simply count activity (like meetings or emails), meaningful KPIs are aligned with strategic priorities and grounded in the organization’s specific context. The best KPIs serve as early-warning systems, highlight emerging risks, and prompt proactive adjustments. In a crisis-prone world, they encourage a stance of anticipation rather than reaction.

To structure resilience measurement in a comprehensive way, many organizations use the Balanced Scorecard-a framework that evaluates performance from four perspectives: financial, customer, internal process, and learning & growth. This multidimensional approach ensures that leaders don’t focus solely on end results, but also on the enablers of resilience: skilled staff, effective processes, and stakeholder trust. For instance, financial KPIs might measure recovery costs, while learning KPIs might track crisis simulation participation.

Within this framework, it is vital to differentiate between leading and lagging indicators. Leading indicators, such as the number of risk assessments conducted or time to detect incidents, signal potential future performance. Lagging indicators, like system downtime or customer attrition post-crisis, reveal the outcome of past efforts. A well-balanced KPI system includes both, giving leaders visibility into what’s coming and what has already occurred.

Beyond scorecards, maturity models provide structured benchmarks for resilience. Frameworks like the NIST Cybersecurity Framework or ENISA’s Resilience Maturity Model describe stages of development from “initial” to “optimized.” These help organizations identify where they stand today and what steps are needed to progress. KPIs act as milestones on this journey, making the path to greater resilience tangible and achievable.

But measurement is only as useful as the discipline behind it. How, when, and with whom metrics are used matters just as much as what is measured. Metrics should be part of the organizational rhythm-not relegated to annual reviews or compliance checklists. The frequency of tracking should reflect the volatility of the risks involved: cybersecurity metrics may require daily attention, while culture-related metrics might be reviewed quarterly. The key is aligning cadence with context.

Benchmarking also adds value, both internally and externally. Internal benchmarking across departments helps identify outliers-areas that excel or struggle disproportionately. External benchmarking against industry peers provides perspective and motivation. If incident response times or training participation lag behind competitors, it signals a need for attention and potential adaptation of best practices.

However, measurement integrity is essential. KPIs must be built on consistent definitions, transparent methodologies, and honest interpretation. Manipulating data to create a rosier picture undermines trust and devalues the process. The most resilient organizations involve diverse stakeholders in designing and reviewing metrics, combining quantitative data with qualitative insights from the frontline. This reduces the risk of “measurement myopia”-focusing only on what’s easy to count, rather than what’s most important.

Most importantly, measurement should be dynamic and iterative. Metrics must evolve with shifting threats and priorities. Dashboards are not static-they must be reviewed, debated, and adjusted. What gets measured should prompt real conversations: What does the data mean? What should we do next? What new questions does this raise? Resilience measurement must be a living process of discovery and action.

A powerful example of this evolution comes from Maersk, the global shipping giant. In 2017, Maersk was devastated by the NotPetya cyberattack. Despite prior investments in security, the attack exposed significant weaknesses in detection, recovery, and communication. In response, Maersk overhauled its resilience metrics. It introduced new KPIs, such as time to detect incidents, recovery speed, and communication effectiveness. It ran regular crisis simulations and red team assessments. Critically, it tracked results on a centralized dashboard reviewed by leadership. The lesson was clear: resilience improves when it is measured-and reviewed-with intent

Chapter 9: Resilience Leadership

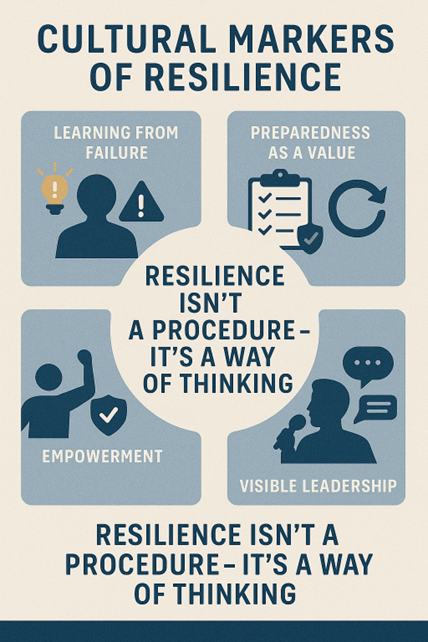

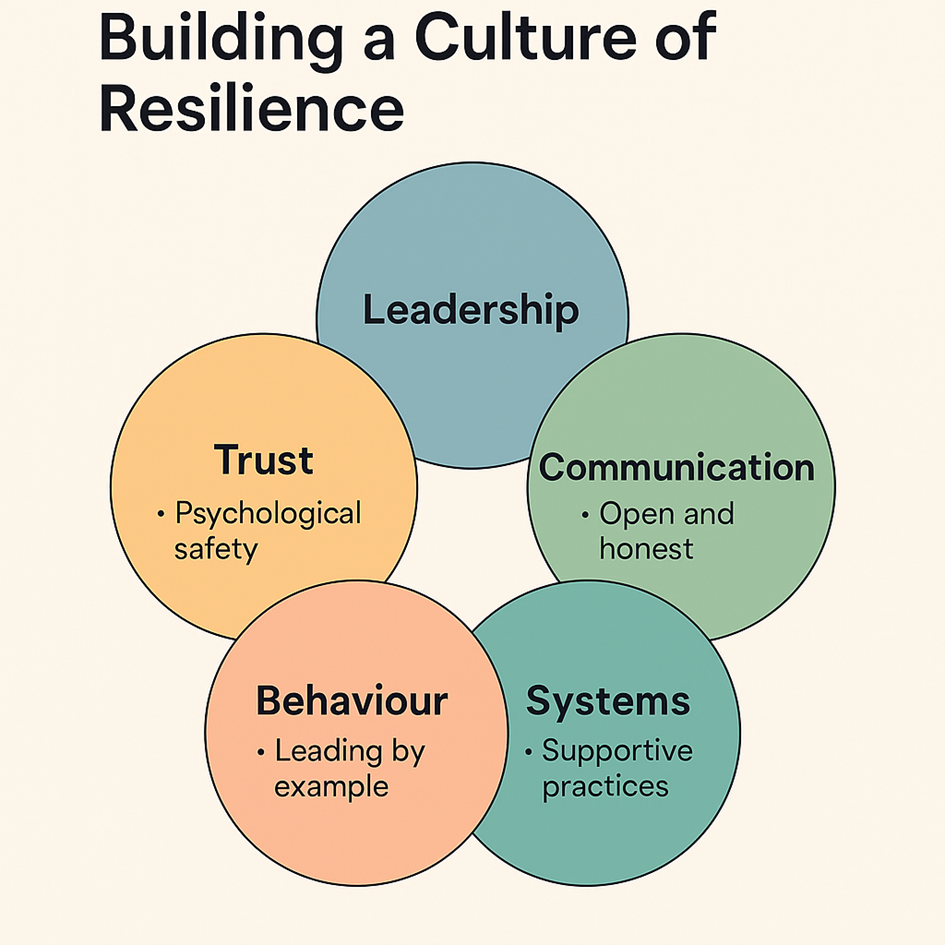

Organizational resilience is not a tool, a procedure, or a policy-it is a way of being. It cannot be installed or audited into existence. True resilience is a behavioural and cultural capability: a shared set of assumptions, norms, and responses that govern how people think, act, and interact under pressure. It determines how organizations absorb disruption, adapt to change, and recover from crisis without losing sight of their purpose. At its core, resilience lives in culture-and culture, more than any other single element, is shaped by leadership.

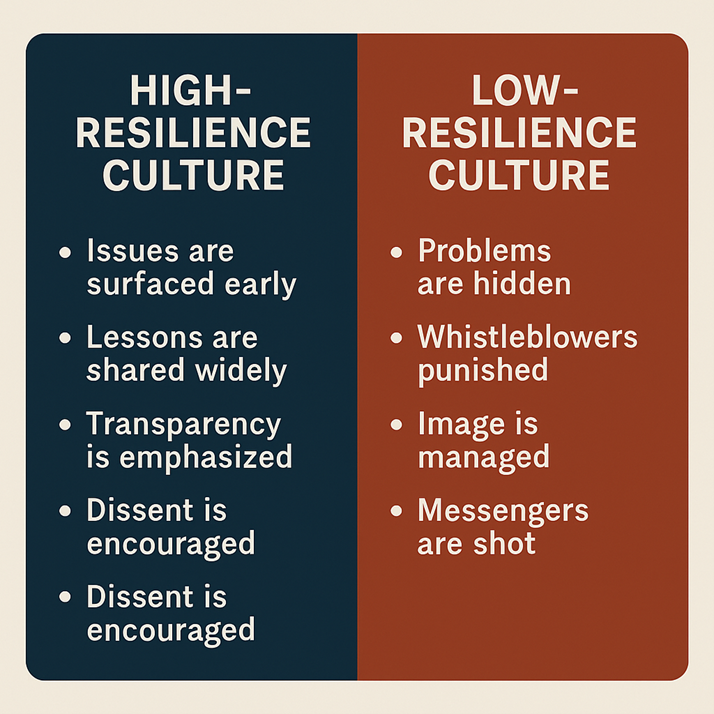

Culture is the invisible infrastructure that determines how people react to stress, communicate under uncertainty, and navigate ambiguity or conflict. It decides whether teams freeze or act, fragment or align, conceal or disclose. Resilient culture is not reactive-it is proactive, grounded in psychological safety, shared responsibility, and leadership consistency. And it begins long before a crisis strikes.

Leadership sets the tone of resilience, not just through formal policies or mission statements, but through everyday behaviour. The most resilient organizations are not necessarily those with the thickest crisis binders. They are the ones where people are trusted to act without waiting for permission. They are the places where speaking up is welcomed, where decisions are made where the facts are clearest, and where initiative is rewarded over obedience. This does not emerge by accident-it is cultivated over time through deliberate leadership modelling: openness, humility, accountability, and respect.

One common misunderstanding is the belief that resilience is only tested in crisis. In reality, it is tested every day-in hallway conversations, decision-making meetings, team conflicts, and unexpected problems. Culture is shaped in these ordinary moments and solidified through repetition. How leaders react when someone makes a mistake, how they respond to dissent, and how they handle bad news all reinforce or undermine the resilience of the organization. Over time, these micro-signals become the organization’s “normal.”

Psychological safety is the foundation of a resilient culture. It is the belief that individuals can express concerns, admit mistakes, ask questions, and challenge assumptions without fear of ridicule or retribution. In crisis, this safety becomes essential-because no system, however advanced, can function well if people are afraid to speak. Silence, driven by fear or hierarchy, erodes readiness faster than any technical deficiency.

Leadership presence plays a central role in maintaining that safety. True presence goes beyond visibility. It means showing up in meetings with attention, asking open questions, listening with empathy, and thanking people for raising uncomfortable truths. The best leaders under pressure are not those who bark orders or project false certainty. They are those who absorb stress, stay calm, and create space for others to perform. In moments of uncertainty, the leader’s demeanour sets the tone for the entire organization.

The military has long demonstrated the power of proximate leadership in high-risk environments. In combat zones, rank matters-but so does presence, consistency, and the ability to communicate intent under pressure. The same holds true in the corporate world. Crisis teams perform best when their leaders are engaged, responsive, and invested in the team’s success-not when they operate from a distance or via disconnected statements.

Storytelling also plays a powerful role in shaping a resilient culture. Organizations create shared meaning through the stories they tell-about past crises, recoveries, and moments of strength or failure. Resilient leaders don’t shy away from difficult stories. They use them to reinforce learning, highlight unsung heroes, and connect current risks to past lessons. Memory, not mythology, is what anchors teams during future disruptions.

However, a common failure of leadership is the gap between stated values and lived behaviour. Saying “we value transparency” while avoiding uncomfortable truths or claiming “we empower teams” while micromanaging every move, undermines credibility. These gaps create cynicism, and cynicism kills resilience. People must believe that their leaders mean what they say, or they will disengage just when their commitment is most needed.

Resilience also requires cross-functional trust and collaboration. Crises never respect organizational boundaries-they cut across IT, legal, HR, operations, and communications. If these functions do not trust each other, or if leadership fails to model unity, the response will falter. Senior leaders must actively bridge silos, resolve turf wars, and reward collaboration. A fragmented leadership team sends a dangerous message: when the pressure rises, alignment breaks.

Cultural alignment also depends on systems and routines. Culture cannot thrive on rhetoric alone. It must be supported by practical scaffolding: regular simulations, honest debriefs, embedded feedback loops, and performance metrics that reflect complexity, not just speed or efficiency. If employees are punished for delay but not rewarded for risk awareness, they will hide problems. If leaders only reward perfection, people will avoid transparency. Systems must reinforce the values that culture seeks to uphold.

In global organizations, culture becomes more complex. Norms differ by geography. What builds trust in one region may be misunderstood in another. Leaders must adapt their style while holding to core principles – respect, clarity, and preparation. Local leadership must be empowered to express resilience in ways that resonate with their teams, not simply implement top.

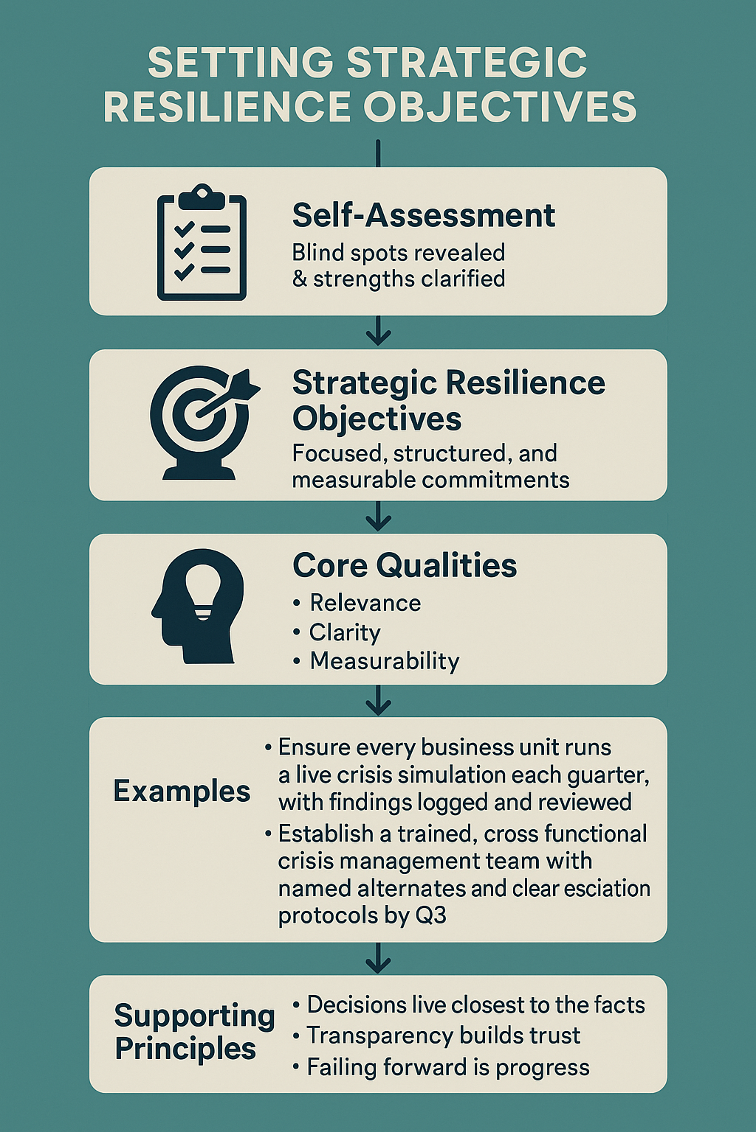

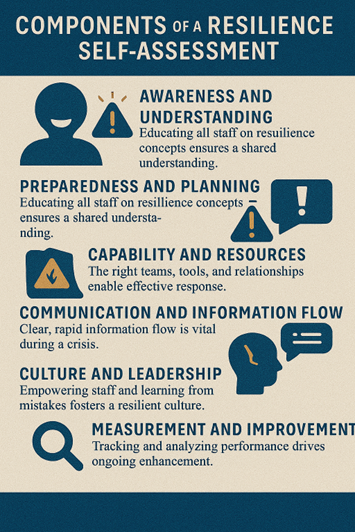

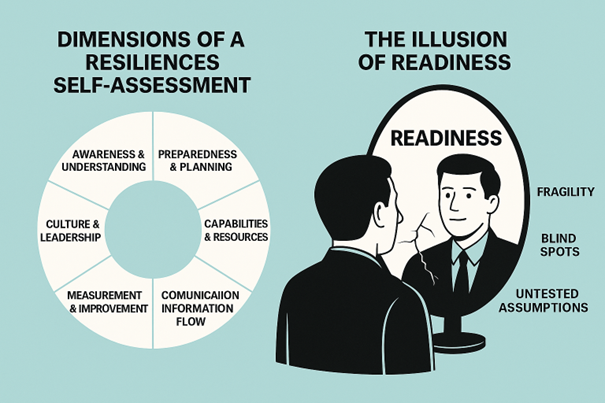

Chapter 10: Self-Assessment

Resilience in organizations is not a software solution, a checklist item, or a policy manual. It is a living, dynamic quality rooted in how people think, decide, and behave-especially under pressure. It is not merely the presence of systems or strategies, but the way people act when those systems are tested. At the heart of this lies culture: the shared beliefs, behaviours, and expectations that shape how teams respond to ambiguity, conflict, and disruption. And more than any other force, that culture is shaped and sustained by leadership.

Resilient organizations are not defined by the number of plans they have on the shelf, but by the mindset their people bring to uncertainty. In such environments, employees feel trusted to act, empowered to raise concerns, and confident that they’ll be supported for speaking up. Resilience thrives not in command-and-control structures, but in cultures where decision-making is distributed, where clarity flows freely, and where initiative is rewarded over obedience. These qualities do not emerge by accident. They are cultivated by leaders through consistent behaviour-by modelling openness, encouraging dialogue, and showing accountability even in the face of failure.

A common misconception is that resilience is only tested in crises. In truth, it is tested every day. It is evident in how decisions are made, how feedback is shared, and how leaders respond to dissent, surprise, and bad news. The daily routines of communication, transparency, and mutual respect form a behavioural infrastructure that either supports or undermines resilience when a true disruption occurs. An organization that tolerates fear, silences doubt or punishes mistakes may appear calm in normal times-but it is brittle when pressure mounts.

Culture is shaped in moments but built through repetition. Every interaction-an email, a meeting, a decision-is a cultural signal. When a frontline employee raises a risk, are they thanked or ignored? When a mistake is made, is it investigated or buried? When new ideas are suggested, are they welcomed or dismissed? Over time, these small signals compound into a set of unspoken rules that define what’s normal. Leaders, through their presence and consistency, set the tone for what’s acceptable, expected, and safe to express.

One of the most critical ingredients in a resilient culture is psychological safety-the belief that it is safe to take interpersonal risks. In such environments, people are more likely to raise issues early, share concerns without fear, and act with greater ownership. This is not about eliminating all conflict or discomfort; it is about building trust that enables honest conversations. When trust is absent, silence takes hold. And silence is toxic in a crisis-it delays decisions, hides problems, and amplifies risk.

Resilient leadership means showing up with presence-not just being visible, but being engaged, listening, admitting what you don’t know, and staying grounded in facts. Strong leaders don’t pretend to be invincible. They invite others to speak, absorb tension without escalating it, and avoid turning uncertainty into blame. In doing so, they anchor the team and create conditions for others to act with clarity and courage.