Brand Leadership – WDP1 (Strategic Foundation)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Brand Leadership is provided by Mr. Duckler Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Mr. Duckler is founder and managing partner of a brand and marketing strategy consultancy based in Chicago, IL. He has over 30 years of line management and strategy consulting experience in branding and marketing, customer and consumer insights, and innovation. He wrote a bestselling book that guides readers on how to build a brand strategy that rises above the noise and monotony—transforming brands from indistinguishable into indispensable. In his most recent book, also a bestseller, he details how societal and technological trends—including transparency and purpose, the emergence of Gen Z, artificial intelligence, augmented/virtual reality, and Web3—will shape the future of marketing and brand-building for years to come. The book features 40+ one-on-one interviews with the world’s most influential Chief Marketing Officers.

Before founding his firm, Mr. Duckler was a senior partner in the New York office of a global brand strategy consultancy, and a partner in the Chicago office of another major global brand consultancy, where he co-led the brand strategy practice area. Over the years, he has successfully led engagements for Fortune 500 companies including ExxonMobil, Deloitte, Boeing, Hyatt Hotels, Best Buy, Carlson Companies, Cox Business, NBC Universal, Wrigley, Manpower Group, Abbott, The Home Depot, cars.com, and LexisNexis. Prior to consulting, he spent 10 years in brand management and consumer and customer marketing for Unilever and The Coca-Cola Company.

Mr. Duckler is also a frequent speaker on key topics related to brand and marketing strategy. In 2021, he delivered a TEDx talk—Define Your Differentiator—at the Cal State-Fullerton TEDx event in Orange County, CA. Over the past 20 years, he has spoken at dozens of high-profile events across five continents. He is a faculty member of the Association of National Advertisers (ANA) Marketing Training & Development Center, where he facilitates workshops for member organizations on key topics related to brand strategy. Mr. Duckler also chaired the American Marketing Association’s (AMA) Annual National Marketing Conference for four consecutive years. Additionally, he is a frequent interview guest on brand- and marketing-related podcasts, including The Backwards Hat CMO, On Branding, The MarTech Podcast, Brands On Brands, and Confessions of a Marketer.

Mr. Duckler earned a B.S. in Business from the University of Minnesota and an M.B.A. from the University of Michigan.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

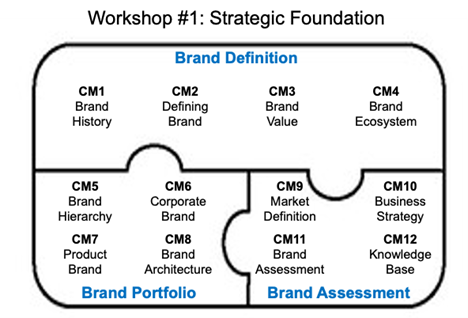

Brands are strategic assets that provide a company with a sustainable competitive advantage in the marketplace. When thoughtfully constructed and consistently activated, strong brands enable an organization to drive short-term business performance (e.g., revenue, market share, profitability), while simultaneously building long-term, sustainable equity for the brand. The mission of this workshop is to lay the foundation for building a superior brand strategy—a strategy which will be implemented throughout the remainder of the Brand Leadership program.

To accomplish this mission, we first need to develop a deep understanding of what a brand is (and is not) and the different types of brands and levels within the organization they exist. It is also important to understand the history of brands, and how the process of managing them has evolved over the years to accommodate changing social, commercial, and technological trends. Perhaps most critical is to understand why brands are so vital to an organization (i.e., they have economic value), and what factors and characteristics tend to translate into superior brand value.

With this foundational understanding in place, we will assess the current state of brand strategy in your organization. This includes introducing the topic of brand architecture (the relationship brands within a portfolio have with one another), along with defining the important nuances that exist between corporate brands and product brands. Finally, we will demonstrate how brand strategy needs to be inextricably linked to the business strategy it is intended to serve. This entails clearly articulating your business strategy and assessing the extent to which your brand currently helps to deliver it.

By the end of this workshop, you will have a solid understanding of the most important concepts related to brand leadership, and how to apply them to your organization.

Objectives

01. To provide a historical overview of the evolution of branding.

02. To define what it means to be a brand, and how it’s much more than merely a name.

03. To demonstrate why brands are so economically valuable to a company.

04. To introduce the duality of the Brand Ecosystem—strategy and execution.

05. To explain different types of brands and how branding works at different levels.

06. To demonstrate the importance of corporate brand, and its role within the portfolio.

07. To demonstrate role of a product brand, and how it differs from a corporate brand.

08. To introduce the key components and best practices of brand architecture.

09. To define the concept of market, and the important role it plays in defining brands.

10. To demonstrate the critical link between business strategy and brand strategy.

11. To assess current brand strategy, and how it aligns with business strategy.

12. To catalog existing information for future program use, and identify gaps to be filled.

Strategies

01. Illustrate how the concept of branding was born, and how it has evolved over time.

02. Provide several definitions for brand that are common in the marketplace today.

03. Explain the concepts of brand value and brand valuation.

04. Demonstrate inter-relationship between various components of Brand Ecosystem.

05. Introduce the notion of brand hierarchy and types.

06. Illustrate the role of the corporate brand within the portfolio.

07. Illustrate the role of product brands within the portfolio.

08. Explain brand architecture, and best practices for implementing it.

09. Demonstrate the relationship between categories, segments, and brands.

10. Introduce, explain, and illustrate the seven key components of business strategy.

11. Assess current brand strategy and whether it aligns with business strategy.

12. Determine what knowledge exists internally; what new information is needed.

Tasks

01. Agree on project team members and their roles throughout the program.

02. Adopt a definition of brand that works for your organization.

03. Qualitatively evaluate the extent to which your brand has economic value.

04. Document the existence (or absence) of various Brand Ecosystem components.

05. Provide real-world examples of brand levels and brand types.

06. Articulate strengths and potential shortcomings of your corporate brand.

07. Articulate strengths and potential shortcomings of your product brand (if applicable).

08. Determine brand architecture; relationships (if any) between portfolio brands.

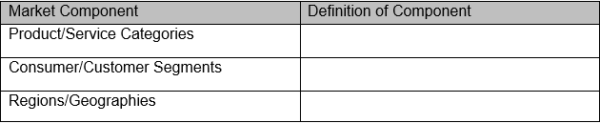

09. Complete the market framework tool: categories, segments and geographies.

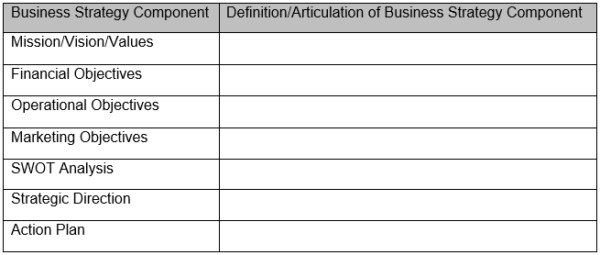

10. Complete the 7-part business strategy framework for your organization.

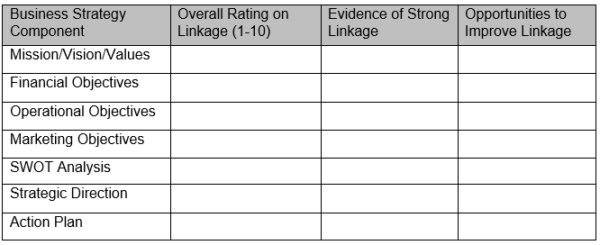

11. Complete the brand strategy assessment framework for your brand.

12. Catalogue existing useful data sources/information; identify knowledge gaps.

Introduction

Welcome to the Brand Leadership program, and more specifically, to the Strategic Foundation workshop. Today marks the beginning of a comprehensive exploration into the world of branding, starting from its very origins and evolving into the modern, intricate landscape that brands inhabit today. This workshop is the first of twelve in the Brand Leadership program, and by the end, you will have established a strong conceptual framework for understanding brands—what they are, how they work, and how they can be leveraged to drive long-term business success in your organization.

Branding is a journey that involves not just the marketing department but the entire organization. It is deeply tied to the company’s purpose, identity, and relationship with its customers. Throughout today’s workshop, we will uncover the fundamental principles of branding, from its historical roots to its diverse applications in the modern world. Whether your brand exists within the realm of products, services, or even corporate identity, today’s session will provide you with the knowledge and practical tools to manage your brand effectively in a fast-paced, ever-evolving business environment.

Today, we will dive into twelve carefully crafted course modules; each one explores a key element of branding, from its definition and value to market articulation and brand architecture. Our goal is not just to educate, but to inspire. You’ll leave this workshop with a deeper understanding of how brands shape the world around us and, more importantly, how you can shape your brand to drive competitive advantage.

The History of Branding: A Journey Through Time

To understand where we are with branding today, we must first look back at its origins. Branding, though often thought of as a modern concept, has its roots deeply embedded in ancient history. Thousands of years ago, artisans, merchants, and tradespeople in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece used symbols to mark their goods and products. These marks weren’t just about identification; they conveyed quality, trust, and ownership. Early consumers—whether they were purchasing grain, pottery, or textiles—would look for these marks as indicators of authenticity and value.

Fast forward a few millennia to medieval Europe, where guilds began standardizing goods through the use of symbolic identifiers. These guilds guaranteed a level of quality, and their marks became synonymous with trust and craftsmanship. This was an early form of what we now consider to be brand equity, where a symbol carried an intrinsic value that could influence a buyer’s decision.

As the world entered the industrial age, branding took on new dimensions. With the mass production of goods, businesses needed to differentiate their products in increasingly crowded markets. Companies like Procter & Gamble, Quaker Oats, and Heinz were some of the first to use branding to create national identities for their products. They didn’t just sell soap, oats, or ketchup—they sold trust, tradition, and consistency. These early pioneers understood that branding was not just about the product itself, but about creating an emotional connection with the consumer.

In the 20th century, branding evolved further as mass media—first radio, then television—gave companies unprecedented access to consumers. Advertising became a powerful tool for shaping brand identities and building consumer loyalty. Iconic brands like Coca-Cola, Ford, and General Electric capitalized on this, creating slogans, jingles, and characters that became deeply ingrained in popular culture. Branding was no longer just a business tactic; it had become a cultural force, capable of shaping consumer habits, preferences, and even societal values.

Today, branding has entered the digital age, where social media, e-commerce, and big data have fundamentally transformed the way brands interact with their audiences. Brands are now omnipresent, communicating with consumers across multiple platforms and touchpoints in real time. The rise of personalization, influencer marketing, and digital storytelling has added new layers of complexity to branding, making it more interactive and participatory than ever before. Consumers now expect brands to be authentic, transparent, and responsive, and brands must navigate this dynamic environment with agility and purpose.

This historical overview provides a foundational context for understanding the modern world of branding. By recognizing how branding has evolved, you will gain insights into the enduring principles that continue to drive successful brands today. During this workshop, we will build on this history to explore the specific elements that make branding such a powerful business function.

What is a Brand? Unpacking the Definition

Having explored the roots of branding, we can now turn to a more practical and contemporary question: What exactly is a brand? While this may seem straightforward, it’s a deceptively complex question. A brand is far more than a logo, tagline, or product; it is the sum-total of a company’s identity, its values, and the experiences it offers to its customers. A brand exists both as a tangible asset—something that can be seen and touched—and as an intangible force that lives in the minds of consumers.

In its simplest form, a brand is an identifier. It helps consumers distinguish one product (or company) from another. But in today’s world, branding goes far beyond identification. A brand represents a promise to the customer—whether that’s a promise of quality, innovation, reliability, or value. It is a set of expectations that shapes how consumers perceive and interact with a company. Brands like Apple, Nike, and Tesla don’t just sell products; they sell experiences, lifestyles, and ideals.

The emotional component of branding is critical. Consumers form emotional connections with brands that resonate with their personal values and beliefs. This is why branding is so powerful—because it taps into the human psyche. When a consumer chooses Starbucks over a local coffee shop or buys an iPhone instead of an Android, they are making more than a functional decision; they are making an emotional and symbolic choice that reflects their identity and aspirations.

This first workshop will dive deep into the different facets of branding. In it, we will explore how brands are defined by their visual identity (such as logos and colors), their verbal identity (including messaging and tone of voice), and their emotional identity (the feelings and associations they evoke in consumers). You will develop a clear understanding of how to define your brand in ways that go beyond the surface and create meaningful connections with your audience.

The Value of Brands: Measuring Both Financial and Emotional Impact

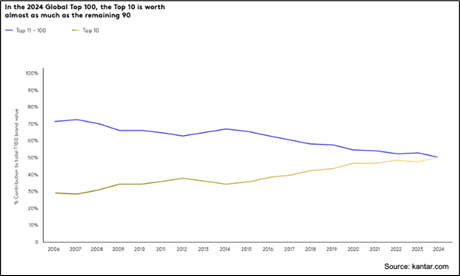

Why do some companies command higher price points, greater customer loyalty, and stronger market positions than others? The answer often lies in the strength of their brands. Brands are among the most valuable assets a company can have, and understanding how to measure and grow that value is essential for any brand leader.

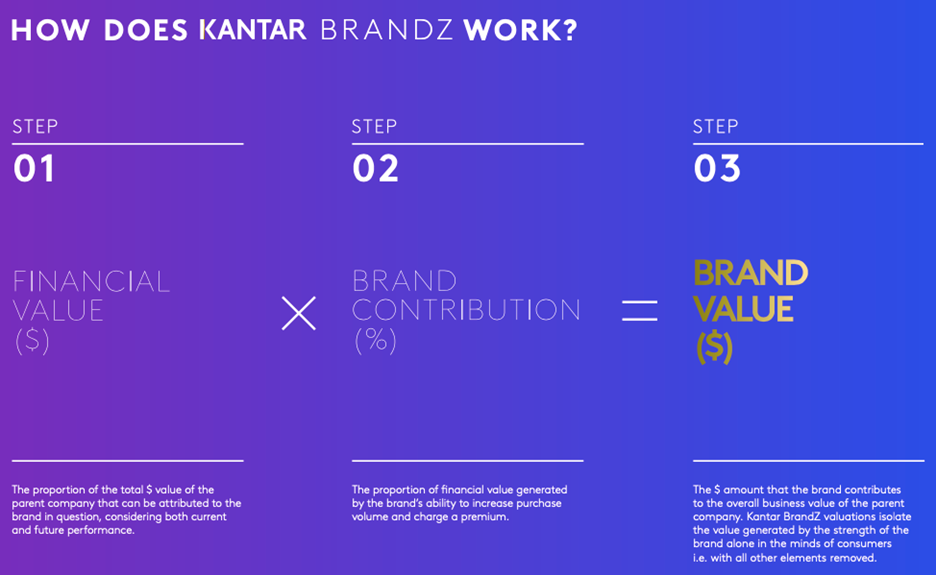

Brand valuation refers to the process of estimating the monetary value of a brand as an intangible asset. An intangible asset is one that does not have a physical presence but contributes to a company’s value. The value of a brand reflects the financial advantage it offers to a company through consumer loyalty, perceived quality, and market positioning. This involves determining the financial worth of the brand itself, separate from the company’s physical assets, products, or services.

Although there are many models for brand valuation—and they differ vastly in their methodology—there are four considerations that typically go into brand valuation. The first is brand strength, which includes consumer perceptions of the brand, brand loyalty, market position, and brand awareness. Stronger brands typically command higher valuations because they attract more customers and sustain long-term financial performance.

The second consideration is financial performance. This is often measured by brand-related revenue, ability to command a premium price point, profit margins, and overall profitability. Unsurprisingly, brands that generate higher revenues and exhibit higher margins relative to competitors are valued more highly.

Next is legal protections. Like any asset, brands need to be protected from harm, neglect, and misuse. Brands that are well-protected by trademarks and other intellectual property laws tend to have higher valuations because they are less vulnerable to competition and other market forces.

The final consideration is growth potential. Growth is a primary objective for most companies, and brands play an instrumental role in driving business growth. Brands that have high potential for future growth—whether through geographic expansion, product line extensions, or penetrating untapped markets—tend to have higher valuations due to greater expected future cash flows.

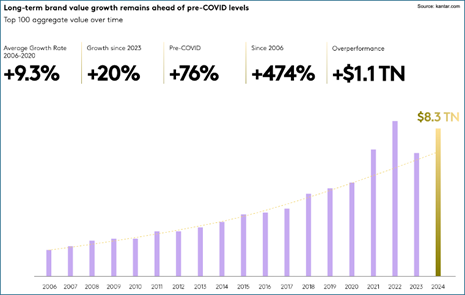

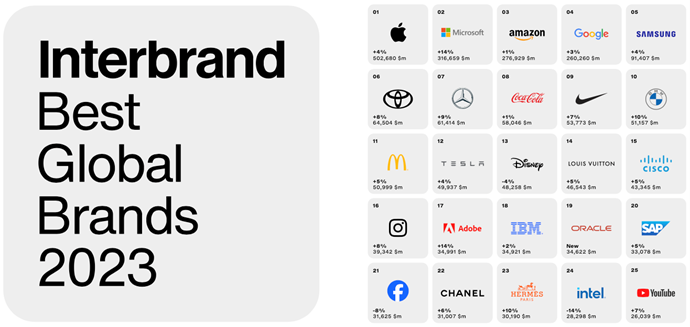

Later in this workshop, we will discuss two specific brand valuation models—Interbrand and Kantar BrandZ—and how companies use these models to assess the worth of their brands during mergers and acquisitions, and when making other strategic, brand-related decisions (e.g., licensing, franchising). By the end of this session, you will have a thorough understanding of what constitutes brand value, and the factors that go into maximizing it.

Brand Value Case: Google — From Startup to Global Brand Powerhouse

Google’s journey from a modest university project to one of the most valuable brands in the world is a remarkable story of technological innovation, market insight, and sustained financial growth. When Larry Page and Sergey Brin began working on their search engine project at Stanford University in 1996, the idea seemed simple: create a tool that would organize the internet’s growing body of information more effectively. Initially called “Backrub,” their technology, based on ranking web pages through the number and quality of backlinks, was groundbreaking. From the outset, Page and Brin were focused on much more than just creating another search engine—they envisioned a new way of navigating the chaotic web. This vision laid the foundation for Google’s brand identity, positioning it as a company that would simplify the internet for users everywhere.

Google’s 2004 Initial Public Offering (IPO) marked a critical inflection point for the company. Listed at $85 per share, Google’s stock price surged on its first day of trading, reflecting investors’ confidence in its business model and future potential. This surge pushed Google’s market valuation to $27 billion. The IPO provided Google with the capital it needed to expand its operations, build out infrastructure, and invest in acquisitions that would further drive its growth. One of the most significant of these acquisitions came in 2006 when Google purchased YouTube for $1.65 billion. At the time, the price tag raised eyebrows, but YouTube would soon prove to be one of the most valuable digital media platforms, significantly boosting Google’s advertising revenues and helping the company maintain its dominance in the digital space.

Perhaps one of the most pivotal moments in Google’s growth trajectory came with the launch of the Android operating system. Acquired in 2005, Android was Google’s entry into the burgeoning mobile market. By 2008, it became clear that smartphones and mobile internet usage would define the next era of technology, and Google positioned itself at the forefront of this shift. Android quickly became the most popular mobile operating system worldwide, allowing Google to extend its advertising business to mobile devices. This strategic expansion into mobile not only boosted Google’s revenue but also solidified its brand presence in the everyday lives of billions of users. Android, along with other key innovations like the Chrome web browser and Google Docs, became central to Google’s ecosystem, driving its market valuation ever higher.

In 2015, Google undertook a corporate restructuring, creating a new parent company, Alphabet Inc. This restructuring allowed Google to separate its highly profitable core businesses, such as search and advertising, from its more experimental ventures like autonomous vehicles and life sciences. From a financial perspective, the move was a strategic triumph. Alphabet’s diversified business structure gave investors clearer insights into where the company’s revenues were coming from, which helped maintain confidence in its long-term growth potential. Alphabet’s market valuation exceeded $1 trillion by early 2020.

Throughout this financial ascent, Google’s brand remained a key driver of its market value. Consistently ranked among the top brands in the world, Google’s brand value exceeded $300 billion by 2023, according to Interbrand’s Best Global Brands report. The company’s name had become synonymous with search, innovation, and digital ubiquity, reinforcing investor confidence and contributing significantly to its overall market valuation. Today, Google is not just a search engine or an advertising platform—it is a global brand deeply embedded in the fabric of the internet, technology, and modern life. It is also one of the most valuable brands in the world.

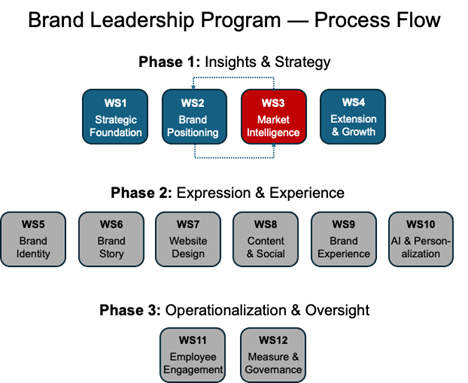

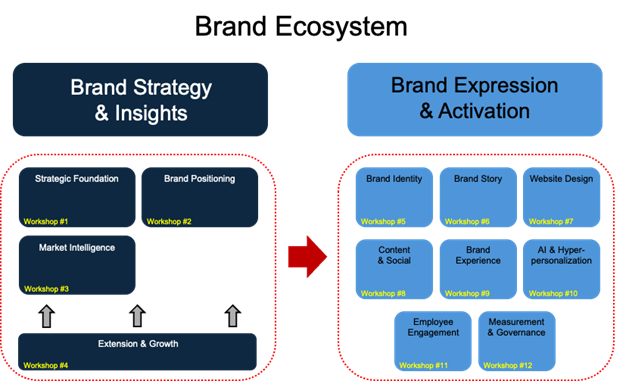

The Brand Ecosystem: Two Sides of Brand

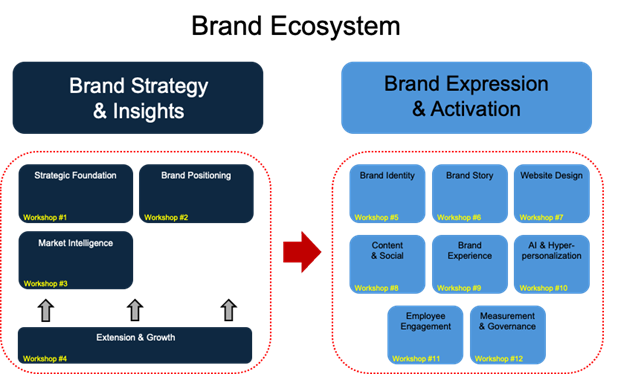

Brands are complex and multi-faceted, and they form a broader ecosystem. As with many other aspects of business, this ecosystem is part strategy and part execution. The strategy component includes brand positioning, brand architecture, and brand growth strategy. Along with market intelligence, these are the topics of the first four workshops in this Brand Leadership program.

The execution component of the ecosystem includes everything we typically associate with brands, because they are the tangible manifestations of branding. Examples of brand execution include visual identity (logos, colors, and design elements that make a brand instantly recognizable) and verbal identity (language, messaging, and tone of voice that convey a brand’s personality and values). They also include brand story, website design, brand experience (interactions customers have with a brand at every stage of their journey), content marketing, social media, and more. Together, these are the “touch points” that shape how a brand is experienced and perceived in the world. Successful brands understand how to manage this ecosystem to create a compelling, unique, seamless, and cohesive experience for their customers.

Think of brands like Amazon or Disney. Every interaction a customer has with these brands—from visiting their website to receiving customer service or attending a theme park—is carefully crafted to reinforce the brand’s identity and values. These companies have created robust brand ecosystems that ensure every touchpoint is aligned with their core promise, creating a unified brand experience that resonates with their audience.

The concept of Brand Ecosystem is embedded in the DNA of the Brand Leadership program. As demonstrated in the exhibit below, each workshop topic represents an important component of the overall program.

Brand Hierarchy and Types: Understanding the Structure of Brands

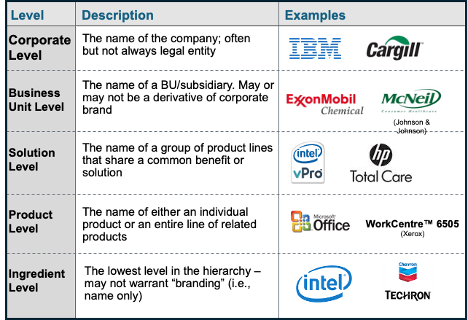

For many companies, branding is not just about managing a single entity—it’s about managing a portfolio of brands, each with its own role within the company’s broader business strategy. This is where the concept of brand “hierarchy” comes into play. Brand hierarchy refers to the level within the organization a brand resides. Five levels will be discussed and illustrated: corporate, BU/division, solution, product, and ingredient.

At the top of the hierarchy is often the corporate brand, which represents the organization as a whole. Beneath that, there may be product brands, which represent individual products or services, or sub-brands, which operate within the context of the corporate brand but have their own distinct identity. Companies like Unilever, Nestlé, and General Motors manage complex brand portfolios, with dozens of brands serving different markets and customer segments.

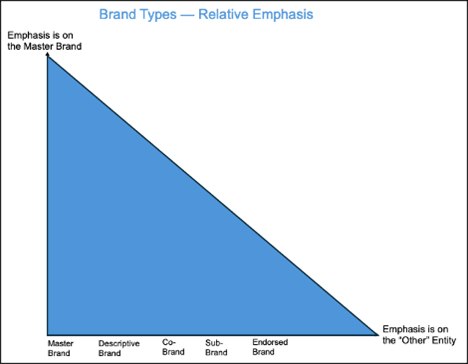

During this workshop, we’ll also explore several different “types” of brands and how they fit into a company’s overall brand portfolio. For example, you’ll learn about master brands (like Google, which lends its name to multiple products), endorsed brands (like Courtyard by Marriott, which is tied to its parent brand while maintaining its own identity), sub-brands (like Amazon Prime, which is a subscription service for the Amazon master brand), and co-brands (like Nike+, a collaboration between Nike and Apple).

Brand Architecture: Structuring Your Brand Portfolio for Success

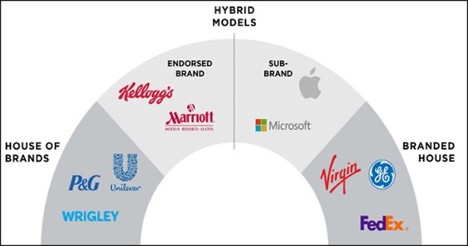

When the above two concepts of brand “hierarchy” and “types” are combined, you essentially have brand architecture. Brand architecture is the strategic framework that defines how brands within a portfolio are organized and how they relate to one another (if at all). It’s about creating a clear, logical and intuitive structure that makes sense to consumers, and maximizes profitability and internal efficiencies for the companies that manage the brands.

In today’s workshop, we will explore different types of brand architecture, including the Branded House (where the corporate brand is the dominant identity, as seen with Google), the House of Brands (where individual brands operate independently, as seen with Procter & Gamble), and hybrid models that combine elements of both. You’ll learn how to assess your brand portfolio and determine the best architecture structure for your business, based on factors like market needs, customer preferences, competitive dynamics, and business strategy. By the end, you’ll have a strategic framework for managing your brand architecture in a way that drives growth, improves efficiency, and enhances individual and collective brand equity.

Corporate Brand: The Heart of the Company

For most companies, corporate brand and product brand represent the two most important types of brands in their portfolio. Corporate brand is more than just a company name or a logo—it is the identity that embodies the company’s mission, vision, and values. We’ll focus on the role of the corporate brand within the portfolio, and how it influences everything from internal culture to external reputation.

Corporate brands are critical because they often (although not always) serve as the foundation upon which all other brands are built. When consumers think of Apple, for example, they don’t just think of iPhones or MacBooks; they think of innovation, creativity, and design excellence. The corporate brand serves as a unifying force that ties all of Apple’s products together under a single, cohesive identity.

But the corporate brand is not just about consumer perception and driving purchase behavior. It also plays a crucial role in building trust with investors, media, regulators, employees, and other stakeholders. A strong corporate brand has been known to attract top talent, drive investor confidence, and inspire loyalty and camaraderie among employees.

Product Brand: Crafting Distinctive Identities for Your Offerings

While the corporate brand sets the stage for the overarching company, product brands focus on the specific products or services a company offers. Sometimes the product brand is closely associated with the corporate brand, where other times it is not. Determining this relationship (or lack thereof) is part of brand architecture, and it is an important strategic choice.

Regardless of proximity to corporate brand, each product brand must carve out its own value proposition within the broader corporate structure, ensuring that it resonates with its target market while staying aligned with the company’s core values.

In this workshop, we will dive into the world of product branding, exploring how companies like Nestlé, General Motors, and Sony manage multiple product brands that cater to different markets, demographic and psychographic consumer segments, and price points. By the end of this session, you’ll understand how to create brands (whether corporate or product) that stand out in a crowded market while reinforcing the overall corporate brand identity.

Defining the Market: Identifying the Competitive Landscape

The critical task of positioning your brand—which will be undertaken in Workshop #2— requires first defining and understanding the market within which it competes. This involves defining not only the product categories it operates in, but also the customer segments and geographic regions being targeted. This is what we refer to as market definition—or the brand’s “frame of reference”—i.e., where it fits within the broader competitive landscape.

Defining the market is the first step in positioning your brand for success, as it helps you understand where you are relative to your competitors and what factors influence your target customers’ buying decisions. By the end of this session, you will have a clear understanding of how to appropriately define your market, and how to eventually use that information to position your brand effectively in the next workshop.

Aligning Brand Strategy with Business Strategy

With market definition articulated, another important aspect of branding is ensuring that brand strategy is fully aligned with business strategy. A successful brand doesn’t exist in isolation—it must support the broader goals of the organization, from driving revenue growth to improving operational efficiency to fulfilling social and other cause-related purposes.

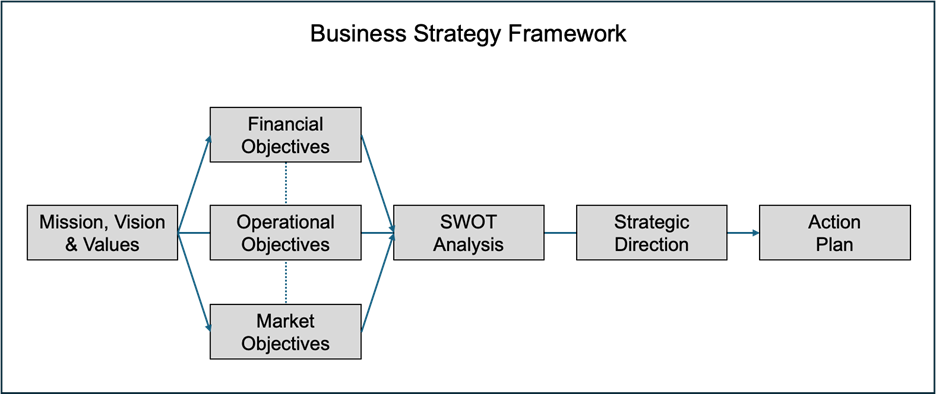

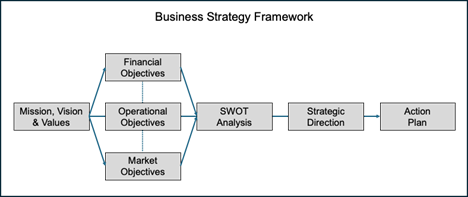

As such, we will explore how key components of your business strategy—e.g., mission, vision, and values, financial, operational and marketing objectives, and more—factor into brand strategy, ensuring that the two are mutually reinforcing. By the end of this session, you will understand the inextricable linkage that needs to exist between business and brand; and the critical role that brand plays in achieving your company’s business objectives.

Building a Knowledge Base for Long-Term Brand Success

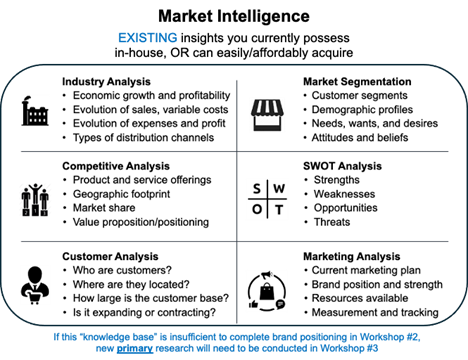

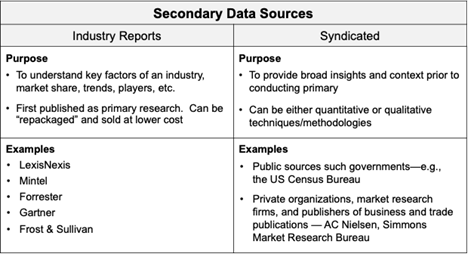

The final course module of today’s workshop focuses on building a knowledge base for your brand. A knowledge base is a repository of data, insights, and strategy that helps guide brand decisions over time. Among other things, it helps you determine the optimal strategic positioning for your brand to occupy.

We will discuss how to collect and organize brand data, from customer feedback and performance metrics to market research and competitive analysis. You’ll learn how to use this data to inform your brand strategy and make informed decisions that drive long-term brand success.

After evaluating your existing knowledge base, you will have an understanding as to whether you have enough information to successfully position your brand during Workshop #2, or if there are knowledge gaps that you’d like to close through conducting new primary market research (Workshop #3). Regardless of which path you choose, you will have a knowledge base that can evolve with your brand, helping you to not only make critical initial decisions—such as brand positioning—but also to adapt to changes in the market while staying true to your brand’s core identity.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: History of Branding

This course module traces the evolution of branding from its early origins in ancient civilizations to its modern-day complexities. It highlights how branding has transitioned from simple marks of ownership in Mesopotamia and Egypt to a sophisticated system of identity, trust, and emotional connection. The course module emphasizes significant milestones, such as the rise of branding during the Industrial Revolution, the birth of national brands like those of Procter & Gamble, and the legal protection of trademarks. It also delves into the role of branding in the age of advertising, emotional branding, and corporate identity.

Moreover, it explores modern-day concepts, including brand equity, digital branding, and the impact of globalization, personalization, and brand activism. Finally, the future of branding is addressed through the integration of artificial intelligence, automation, and immersive technologies like virtual and augmented reality. Ultimately, the content contained in this course module underscores branding’s enduring role in shaping consumer trust, loyalty, and differentiation in a competitive, ever-evolving marketplace.

Chapter 2: Defining Brand

The “Defining Brand” module delves into the multi-dimensional nature of a brand, showcasing several influential perspectives on the topic. David Aaker, Seth Godin, and Walter Landor offer varied definitions, emphasizing that a brand is both a tangible identifier and a psychological perception, rooted in consumer experiences. The majority of the module is dedicated to illustrating the myriad different ways to define a brand, including its role as an emotional connector, cultural construct, marketing tool, personal relationship, customer experience, trademark, and legal asset. Through these lenses, and several others, brands serve not only as a means for differentiation but also as critical assets that shape customer perceptions and drive business success. In total, the course module proposes a holistic understanding of branding, focusing on both strategy and execution for long-term market impact and business success.

Chapter 3: Brand Value & Valuation

The course module “Brand Value & Valuation” provides an in-depth exploration of the financial and strategic significance of brand value, particularly focusing on the measurable benefits of strong brands. It highlights nine key advantages enjoyed by top brands, including superior stock market performance, premium pricing power, greater consumer preference, market penetration, and resilience during economic downturns. The course module also explains how strong brands drive long-term profitability through innovation, market share dominance, and employee engagement. The back half of the course module delves into the methodologies used for brand valuation, such as the income approach, market approach, and cost approach, with specific attention to popular surveys and models like Interbrand’s Best Global Brands and Kantar’s BrandZ. Additionally, it presents a case study on the Kraft-Heinz merger, illustrating the role brand valuation served in facilitating that complex M&A transaction. Overall, the course module underscores the importance of quantifying brand value for strategic decision-making, investor relations, and maintaining a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

Chapter 4: Brand Ecosystem

The “Brand Ecosystem” course module presents a comprehensive framework for effective brand management, emphasizing the interplay between strategy and execution. It introduces key components of brand strategy, such as portfolio foundation, brand positioning, and extension and growth. The portfolio foundation defines brand hierarchies and the need for alignment with business strategy, while brand positioning serves as the guiding “North Star” for activation, ensuring relevance and differentiation.

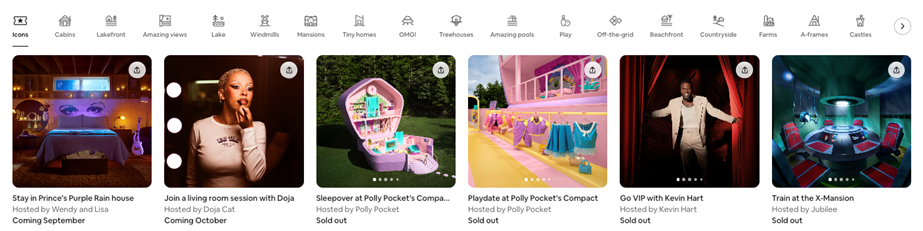

The course module also covers essential aspects of brand activation, including brand identity, storytelling, website design, and content marketing. It highlights the growing role of AI and hyper-personalization in modern branding and the importance of employee engagement in delivering the brand experience. Finally, it emphasizes the need for ongoing brand measurement and governance to track performance and guide strategy. At the end, a comprehensive case study of Airbnb illustrates how a methodical approach to brand-building—based on core consumer insights, strategy development, creative expression, and consistent activation—can lead to brand leadership.

Chapter 5: Brand Hierarchy & Types

The course module “Brand Hierarchy & Types” outlines key concepts in brand architecture, focusing on two main ideas: brand hierarchy and brand types. Brand “hierarchy” refers to the different levels within an organization where branding occurs, including corporate, business unit, solution, product, and ingredient levels. These layers help companies strategically manage their branding across diverse product lines and/or business segments. For instance, corporate brands like Apple or IBM operate at the highest level, whereas solution brands like Microsoft Azure offer a comprehensive approach to solving clusters of customer needs.

The second part of the course module covers five primary brand “types”: master brands, endorsed brands, co-brands, sub-brands, and descriptive brands. These brand types help companies structure their branding strategies to target specific markets while leveraging the overall brand’s strength. For example, master brands like Virgin span multiple product lines, while co-brands like GoPro and Red Bull illustrate successful co-branding partnerships. Importantly, this course module sets the stage for the role of brand architecture in shaping a company’s market presence (Course Module 8).

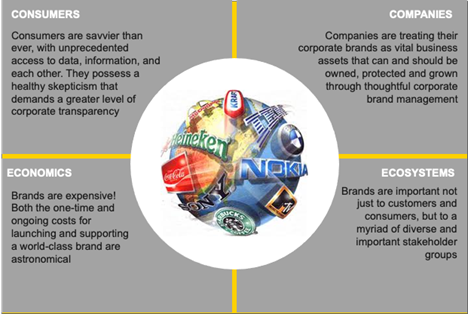

Chapter 6: Corporate Brand

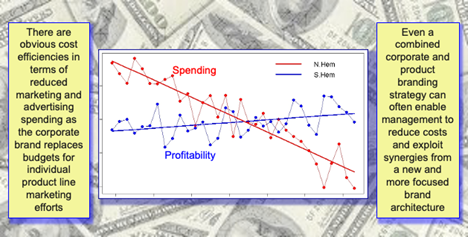

The “Corporate Brand” course module provides a comprehensive examination of corporate branding, distinguishing it from product and other types of branding. It emphasizes the unique strategic role a corporate brand plays in fostering loyalty, trust, and engagement. Key topics include the rising importance of corporate branding, which has become evident through increased advertising spend on corporate brands. The course module outlines the financial benefits of strong corporate brands, including enhanced market valuation and influence on M&A activity. It also explores how corporate brands serve as a vital asset during crises, helping organizations navigate challenges and maintain public trust. Furthermore, corporate branding supports market penetration, cost-effective operations, and fosters internal esprit de corps, enhancing employee pride and engagement. Through numerous real-world examples, the course module illustrates the enduring power of corporate brands in driving long-term success, making them invaluable assets regardless of sector or industry.

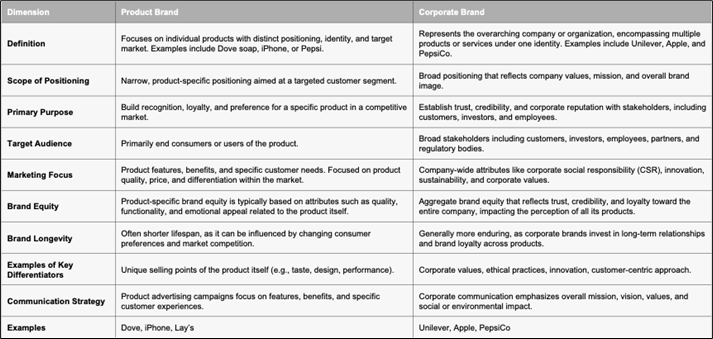

Chapter 7: Product Brand

The course module on “Product Brand” provides a comprehensive exploration of the distinctions and synergies between product branding and corporate branding. Product branding focuses on creating a unique identity for specific products, aiming to differentiate them in the marketplace and drive consumer loyalty. In contrast, corporate branding (per the previous course module) represents the overall perception of the company and must appeal to a broader array of stakeholders, including investors and employees. This course module delves into the core elements of product branding, such as its focus on driving consumer preference, loyalty, and immediate calls-to-action. It also highlights the importance of emotional connections, brand architecture, longevity, and the financial value important to all types of brands. The course module concludes with a product branding case study on the iPhone, which illustrates the harmonious relationship between corporate and product branding, and it emphasizes the strategic importance of aligning a company’s overarching identity with its product lines.

Chapter 8: Brand Architecture

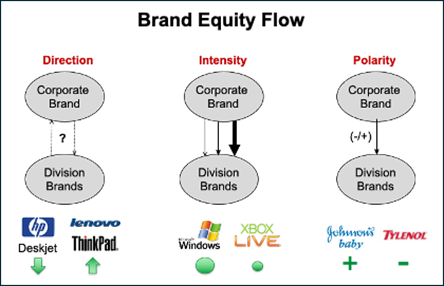

This course module integrates the concepts from the three previous course modules on brand hierarchy and types. It provides an in-depth overview of brand architecture, focusing on how companies structure and manage their brand portfolios. It explains the continuum from a “Branded House” (where a single master brand, like Apple, dominates) to a “House of Brands” (where multiple brands operate independently, as with Unilever). The hybrid approach, which lies between these extremes, is also explored. Key considerations for determining optimal brand portfolio structure include the number of customer segments, the breadth of product offerings, the relevance of the corporate brand, investment levels in branding, and the company’s brand management competency. Additionally, the concept of “brand equity flow” is introduced, which refers to the strategic transfer of brand equity between related brands. Real-world examples, like FedEx’s acquisition and rebranding of Kinko’s, illustrate these principles. The course module also offers guidance on evaluating a company’s brand portfolio to determine if an alternative brand architecture would be optimal.

Chapter 9: Market Definition

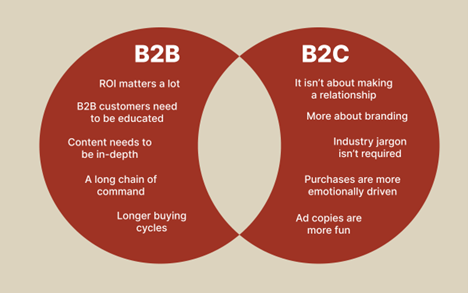

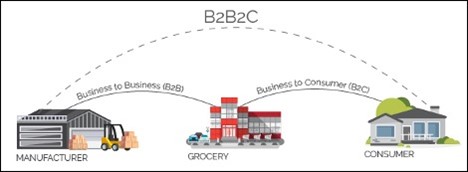

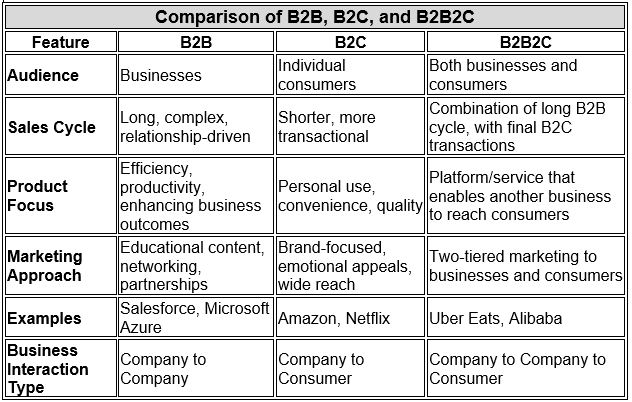

The “Market Definition” course module defines a market as the collective interaction of buyers and sellers for specific products and services within a designated area, either physical or virtual. It outlines the three primary business models—B2B (Business-to-Business), B2C (Business-to-Consumer), and B2B2C (Business-to-Business-to-Consumer)—emphasizing their distinct dynamics. The B2B model involves complex, long-term partnerships between companies, while the B2C model focuses on direct transactions with individual consumers. B2B2C acts as a hybrid, where a business serves consumers through another business, as seen with digital platforms like Uber Eats.

Additionally, the course module discusses market segmentation based on three components: product/service categories, consumer/customer segments, and geographic regions. Effective segmentation helps businesses optimize their strategies by targeting specific groups, thereby improving satisfaction and unlocking growth opportunities. The course module concludes with a case study of Deloitte, highlighting how its diverse service offerings align with different industry sectors. Understanding market definition will be important in Workshop #2 on brand positioning.

Chapter 10: Business Strategy

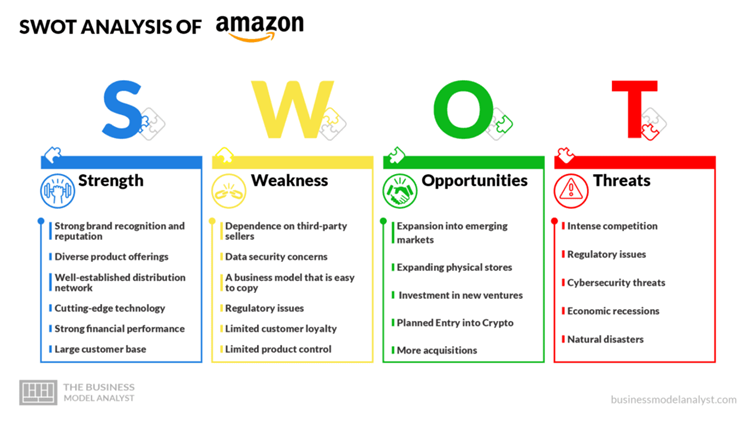

The “Business Strategy” course module provides a comprehensive framework for aligning brand strategy with business strategy. It emphasizes that brand strategy should not be developed in isolation but instead closely linked to overarching business strategy. Through illustrative examples from companies like Disney, Starbucks, and Amazon, this course module demonstrates how aligning both strategies (business and brand) leads to smarter decision-making, efficient resource allocation, consistent customer experiences, and long-term success. Key components of business strategy—vision, mission, values, financial and operational objectives, market goals, SWOT analysis, and action plans—are explained in detail. By examining each of these, companies can develop a cohesive approach that ensures both improved business profitability and increased, long-term brand equity. The course module also includes a case study of Tesla, outlining how the framework could be applied to their business strategy. Following the workshop, participants will be asked to formally document their business strategy within the above framework.

Chapter 11: Brand Assessment

“Brand Assessment” focuses on assessing the alignment between a company’s brand and its business strategy. It re-introduces the seven-component business strategy framework from the previous course module as a means for determining how well a brand fits within the business strategy, including mission, vision, and values alignment, financial objectives, operational objectives, marketing objectives, SWOT analysis, strategic objectives, and action plans. Each component is examined through detailed criteria such as cultural fit, employee advocacy, and scalability.

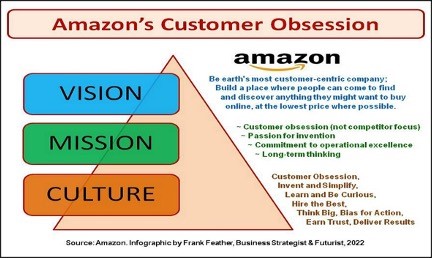

The course module provides questions for assessing the brand’s performance in these areas, helping organizations identify strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for better alignment. Additionally, a case study of Amazon is used to demonstrate the assessment process, highlighting both strong brand-business alignment and areas potentially needing improvement. The module also includes an exercise for participants to rate their own brand’s alignment with business strategy, emphasizing the importance of continuous evaluation for maintaining a competitive and coherent brand identity.

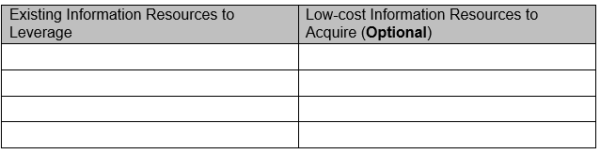

Chapter 12: Knowledge Base

“Knowledge Base,” the final course module of this workshop, focuses on guiding participants through an exercise of evaluating their current information/knowledge base to identify potential sources for the Brand Leadership program. It emphasizes the importance of assessing existing knowledge resources before determining the need for potentially conducting new primary market research, which will be covered in a future workshop. The course module outlines two key sources of data to leverage: in-house resources (like brand guidelines, market performance data, and customer insights) and external sources (such as market research and competitive analysis). These resources are critical for crafting a brand positioning strategy (which will be the primary task in Workshop #2) that aligns with the company’s mission and market realities.

The course module also demonstrates how information sources that are vital to brand positioning may also be potentially useful for subsequent phases of the program, including expression, experience, operationalization, and oversight. Net-net, it encourages participants to consider internal, external, qualitative, and quantitative resources for both immediate brand positioning and future, brand-related decision-making.

Please see below for an illustrative overview of the 12 course modules that comprise Workshop #1.

Curriculum

Brand Leadership – WDP1 (Strategic Foundation)

- History of Branding

- Defining Brand

- Brand Value & Valuation

- Brand Ecosystem

- Brand Hierarchy & Types

- Corporate Brand

- Product Brand

- Brand Architecture

- Market Definition

- Business Strategy

- Brand Assessment

- Knowledge Base

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Brand Leadership corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

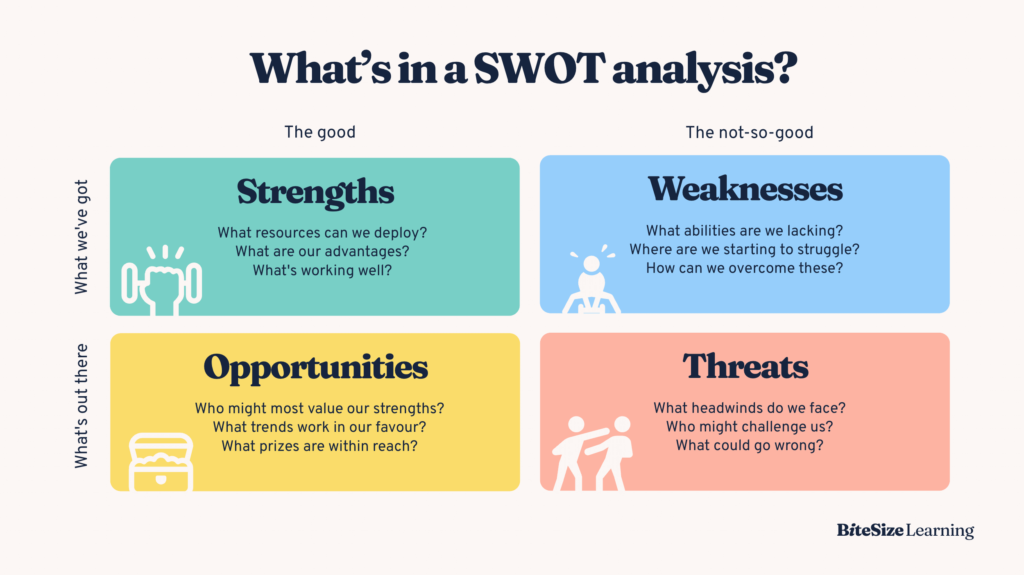

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast

As a guide, the Appleton Greene Brand Leadership corporate training program should take 12-18 months to complete, depending upon your availability and current commitments. The reason why there is such a variance in time estimates is because every student is an individual, with differing productivity levels and different commitments. These differentiations are then exaggerated by the fact that this is a distance-learning program, which incorporates the practical integration of academic theory as an as a part of the training program. Consequently all of the project studies are real, which means that important decisions and compromises need to be made. You will want to get things right and will need to be patient with your expectations in order to ensure that they are. We would always recommend that you are prudent with your own task and time forecasts, but you still need to develop them and have a clear indication of what are realistic expectations in your case. With reference to your time planning: consider the time that you can realistically dedicate towards study with the program every week; calculate how long it should take you to complete the program, using the guidelines featured here; then break the program down into logical modules and allocate a suitable proportion of time to each of them, these will be your milestones; you can create a time plan by using a spreadsheet on your computer, or a personal organizer such as MS Outlook, you could also use a financial forecasting software; break your time forecasts down into manageable chunks of time, the more specific you can be, the more productive and accurate your time management will be; finally, use formulas where possible to do your time calculations for you, because this will help later on when your forecasts need to change in line with actual performance. With reference to your task planning: refer to your list of tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve your program objectives; with reference to your time plan, calculate when each task should be implemented; remember that you are not estimating when your objectives will be achieved, but when you will need to focus upon implementing the corresponding tasks; you also need to ensure that each task is implemented in conjunction with the associated training modules which are relevant; then break each single task down into a list of specific to do’s, say approximately ten to do’s for each task and enter these into your study plan; once again you could use MS Outlook to incorporate both your time and task planning and this could constitute your study plan; you could also use a project management software like MS Project. You should now have a clear and realistic forecast detailing when you can expect to be able to do something about undertaking the tasks to achieve your program objectives.

Performance management

It is one thing to develop your study forecast, it is quite another to monitor your progress. Ultimately it is less important whether you achieve your original study forecast and more important that you update it so that it constantly remains realistic in line with your performance. As you begin to work through the program, you will begin to have more of an idea about your own personal performance and productivity levels as a distance-learner. Once you have completed your first study module, you should re-evaluate your study forecast for both time and tasks, so that they reflect your actual performance level achieved. In order to achieve this you must first time yourself while training by using an alarm clock. Set the alarm for hourly intervals and make a note of how far you have come within that time. You can then make a note of your actual performance on your study plan and then compare your performance against your forecast. Then consider the reasons that have contributed towards your performance level, whether they are positive or negative and make a considered adjustment to your future forecasts as a result. Given time, you should start achieving your forecasts regularly.

With reference to time management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual time taken in your study plan; consider your successes with time-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; consider your failures with time-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to time planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your time expectations. You need to be consistent with your time management, otherwise you will never complete your studies. This will either be because you are not contributing enough time to your studies, or you will become less efficient with the time that you do allocate to your studies. Remember, if you are not in control of your studies, they can just become yet another cause of stress for you.

With reference to your task management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual tasks that you have undertaken in your study plan; consider your successes with task-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case; take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; consider your failures with task-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to task planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your task expectations. You need to be consistent with your task management, otherwise you will never know whether you are achieving your program objectives or not.

Keeping in touch

You will have access to qualified and experienced professors and tutors who are responsible for providing tutorial support for your particular training program. So don’t be shy about letting them know how you are getting on. We keep electronic records of all tutorial support emails so that professors and tutors can review previous correspondence before considering an individual response. It also means that there is a record of all communications between you and your professors and tutors and this helps to avoid any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation. If you have a problem relating to the program, share it with them via email. It is likely that they have come across the same problem before and are usually able to make helpful suggestions and steer you in the right direction. To learn more about when and how to use tutorial support, please refer to the Tutorial Support section of this student information guide. This will help you to ensure that you are making the most of tutorial support that is available to you and will ultimately contribute towards your success and enjoyment with your training program.

Work colleagues and family

You should certainly discuss your program study progress with your colleagues, friends and your family. Appleton Greene training programs are very practical. They require you to seek information from other people, to plan, develop and implement processes with other people and to achieve feedback from other people in relation to viability and productivity. You will therefore have plenty of opportunities to test your ideas and enlist the views of others. People tend to be sympathetic towards distance-learners, so don’t bottle it all up in yourself. Get out there and share it! It is also likely that your family and colleagues are going to benefit from your labors with the program, so they are likely to be much more interested in being involved than you might think. Be bold about delegating work to those who might benefit themselves. This is a great way to achieve understanding and commitment from people who you may later rely upon for process implementation. Share your experiences with your friends and family.

Making it relevant

The key to successful learning is to make it relevant to your own individual circumstances. At all times you should be trying to make bridges between the content of the program and your own situation. Whether you achieve this through quiet reflection or through interactive discussion with your colleagues, client partners or your family, remember that it is the most important and rewarding aspect of translating your studies into real self-improvement. You should be clear about how you want the program to benefit you. This involves setting clear study objectives in relation to the content of the course in terms of understanding, concepts, completing research or reviewing activities and relating the content of the modules to your own situation. Your objectives may understandably change as you work through the program, in which case you should enter the revised objectives on your study plan so that you have a permanent reminder of what you are trying to achieve, when and why.

Distance-learning check-list

Prepare your study environment, your study tools and rules.

Undertake detailed self-assessment in terms of your ability as a learner.

Create a format for your study plan.

Consider your study objectives and tasks.

Create a study forecast.

Assess your study performance.

Re-evaluate your study forecast.

Be consistent when managing your study plan.

Use your Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) for tutorial support.

Make sure you keep in touch with those around you.

Tutorial Support

Programs

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. They are implemented over a sustainable period of time and professional support is consistently provided by qualified learning providers and specialist consultants.

Support available

You will have a designated Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and an Accredited Consultant and we encourage you to communicate with them as much as possible. In all cases tutorial support is provided online because we can then keep a record of all communications to ensure that tutorial support remains consistent. You would also be forwarding your work to the tutorial support unit for evaluation and assessment. You will receive individual feedback on all of the work that you undertake on a one-to-one basis, together with specific recommendations for anything that may need to be changed in order to achieve a pass with merit or a pass with distinction and you then have as many opportunities as you may need to re-submit project studies until they meet with the required standard. Consequently the only reason that you should really fail (CLP) is if you do not do the work. It makes no difference to us whether a student takes 12 months or 18 months to complete the program, what matters is that in all cases the same quality standard will have been achieved.

Support Process

Please forward all of your future emails to the designated (CLP) Tutorial Support Unit email address that has been provided and please do not duplicate or copy your emails to other AGC email accounts as this will just cause unnecessary administration. Please note that emails are always answered as quickly as possible but you will need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general tutorial support emails during busy periods, because emails are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. You will also need to allow a period of up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Please therefore kindly allow for this within your time planning. All communications are managed online via email because it enables tutorial service support managers to review other communications which have been received before responding and it ensures that there is a copy of all communications retained on file for future reference. All communications will be stored within your personal (CLP) study file here at Appleton Greene throughout your designated study period. If you need any assistance or clarification at any time, please do not hesitate to contact us by forwarding an email and remember that we are here to help. If you have any questions, please list and number your questions succinctly and you can then be sure of receiving specific answers to each and every query.

Time Management

It takes approximately 1 Year to complete the Brand Leadership corporate training program, incorporating 12 x 6-hour monthly workshops. Each student will also need to contribute approximately 4 hours per week over 1 Year of their personal time. Students can study from home or work at their own pace and are responsible for managing their own study plan. There are no formal examinations and students are evaluated and assessed based upon their project study submissions, together with the quality of their internal analysis and supporting documents. They can contribute more time towards study when they have the time to do so and can contribute less time when they are busy. All students tend to be in full time employment while studying and the Brand Leadership program is purposely designed to accommodate this, so there is plenty of flexibility in terms of time management. It makes no difference to us at Appleton Greene, whether individuals take 12-18 months to complete this program. What matters is that in all cases the same standard of quality will have been achieved with the standard and bespoke programs that have been developed.

Distance Learning Guide

The distance learning guide should be your first port of call when starting your training program. It will help you when you are planning how and when to study, how to create the right environment and how to establish the right frame of mind. If you can lay the foundations properly during the planning stage, then it will contribute to your enjoyment and productivity while training later. The guide helps to change your lifestyle in order to accommodate time for study and to cultivate good study habits. It helps you to chart your progress so that you can measure your performance and achieve your goals. It explains the tools that you will need for study and how to make them work. It also explains how to translate academic theory into practical reality. Spend some time now working through your distance learning guide and make sure that you have firm foundations in place so that you can make the most of your distance learning program. There is no requirement for you to attend training workshops or classes at Appleton Greene offices. The entire program is undertaken online, program course manuals and project studies are administered via the Appleton Greene web site and via email, so you are able to study at your own pace and in the comfort of your own home or office as long as you have a computer and access to the internet.

How To Study

The how to study guide provides students with a clear understanding of the Appleton Greene facilitation via distance learning training methods and enables students to obtain a clear overview of the training program content. It enables students to understand the step-by-step training methods used by Appleton Greene and how course manuals are integrated with project studies. It explains the research and development that is required and the need to provide evidence and references to support your statements. It also enables students to understand precisely what will be required of them in order to achieve a pass with merit and a pass with distinction for individual project studies and provides useful guidance on how to be innovative and creative when developing your Unique Program Proposition (UPP).

Tutorial Support

Tutorial support for the Appleton Greene Brand Leadership corporate training program is provided online either through the Appleton Greene Client Support Portal (CSP), or via email. All tutorial support requests are facilitated by a designated Program Administration Manager (PAM). They are responsible for deciding which professor or tutor is the most appropriate option relating to the support required and then the tutorial support request is forwarded onto them. Once the professor or tutor has completed the tutorial support request and answered any questions that have been asked, this communication is then returned to the student via email by the designated Program Administration Manager (PAM). This enables all tutorial support, between students, professors and tutors, to be facilitated by the designated Program Administration Manager (PAM) efficiently and securely through the email account. You will therefore need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general support queries and up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies, because all tutorial support requests are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Consequently you need to put some thought into the management of your tutorial support procedure in order to ensure that your study plan is feasible and to obtain the maximum possible benefit from tutorial support during your period of study. Please retain copies of your tutorial support emails for future reference. Please ensure that ALL of your tutorial support emails are set out using the format as suggested within your guide to tutorial support. Your tutorial support emails need to be referenced clearly to the specific part of the course manual or project study which you are working on at any given time. You also need to list and number any questions that you would like to ask, up to a maximum of five questions within each tutorial support email. Remember the more specific you can be with your questions the more specific your answers will be too and this will help you to avoid any unnecessary misunderstanding, misinterpretation, or duplication. The guide to tutorial support is intended to help you to understand how and when to use support in order to ensure that you get the most out of your training program. Appleton Greene training programs are designed to enable you to do things for yourself. They provide you with a structure or a framework and we use tutorial support to facilitate students while they practically implement what they learn. In other words, we are enabling students to do things for themselves. The benefits of distance learning via facilitation are considerable and are much more sustainable in the long-term than traditional short-term knowledge sharing programs. Consequently you should learn how and when to use tutorial support so that you can maximize the benefits from your learning experience with Appleton Greene. This guide describes the purpose of each training function and how to use them and how to use tutorial support in relation to each aspect of the training program. It also provides useful tips and guidance with regard to best practice.

Tutorial Support Tips

Students are often unsure about how and when to use tutorial support with Appleton Greene. This Tip List will help you to understand more about how to achieve the most from using tutorial support. Refer to it regularly to ensure that you are continuing to use the service properly. Tutorial support is critical to the success of your training experience, but it is important to understand when and how to use it in order to maximize the benefit that you receive. It is no coincidence that those students who succeed are those that learn how to be positive, proactive and productive when using tutorial support.

Be positive and friendly with your tutorial support emails

Remember that if you forward an email to the tutorial support unit, you are dealing with real people. “Do unto others as you would expect others to do unto you”. If you are positive, complimentary and generally friendly in your emails, you will generate a similar response in return. This will be more enjoyable, productive and rewarding for you in the long-term.

Think about the impression that you want to create

Every time that you communicate, you create an impression, which can be either positive or negative, so put some thought into the impression that you want to create. Remember that copies of all tutorial support emails are stored electronically and tutors will always refer to prior correspondence before responding to any current emails. Over a period of time, a general opinion will be arrived at in relation to your character, attitude and ability. Try to manage your own frustrations, mood swings and temperament professionally, without involving the tutorial support team. Demonstrating frustration or a lack of patience is a weakness and will be interpreted as such. The good thing about communicating in writing, is that you will have the time to consider your content carefully, you can review it and proof-read it before sending your email to Appleton Greene and this should help you to communicate more professionally, consistently and to avoid any unnecessary knee-jerk reactions to individual situations as and when they may arise. Please also remember that the CLP Tutorial Support Unit will not just be responsible for evaluating and assessing the quality of your work, they will also be responsible for providing recommendations to other learning providers and to client contacts within the Appleton Greene global client network, so do be in control of your own emotions and try to create a good impression.

Remember that quality is preferred to quantity