Behavioral Science – Workshop 1 (Successful Planning)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Behavioral Science is provided by Dr. Heft Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Dr. Heft is Behavioral Scientist and Psychologist dedicated to helping people and organizations become more successful. Understanding that we, as humans, are surprisingly unaware of why we do what we do and what influences our decisions, she is committed to leveraging the power of behavioral science to improve lives. Dr. Heft delivers science-based solutions that drive higher performance through consulting, training, and coaching. She has over 25 years of experience in Fortune 500 companies as an internal consultant. Her educational background includes a Bachelor of Science degree in Business Administration, a Master’s in Psychology, and a Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology. Dr. Heft started a Behavioral Science function at a large financial services firm, where she applied the insights of Behavioral Science to the table to solve a wide range of challenges. One of the larger scale projects included conducting a multi-year research project to align behavioral science research related to motivation, reward, and recognition systems to drive performance. In addition, recognizing individual differences in motivation, they segmented the sales group to tailor solutions and drive performance. Today, she continues to consult with them on major projects and conducts research to leverage behavioral science principles to get better results. Since she worked as an internal consultant, Dr. Heft has a deep understanding of the opportunities and challenges facing you. This background helped her build a Behavioral Science program that is extremely practical and focused on helping you navigate your organization to deliver better results every day.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

The first module, Successful Planning, guides participants in taking the necessary steps to establish a successful project. Planning is often an overlooked but extremely critical part of a BS project. During the workshop, participants will gain an understanding of their role as the process leader, the roles of other stakeholders, and best practices for engaging with their stakeholders. In order to effectively prepare, they’ll be introduced to several key planning tools. More importantly, they’ll be provided with a foundation for the basic components of data collection, analysis, and reporting. Getting a head start on data collection is a vital ingredient for facilitating a successful project.

Objectives

01. Start Planning: Identify the critical factors involved in embedding the BS Process in your organization. Prepare the BS Process Leader for a Successful Launch.

02. Process Leader: Gain a deep understanding of the various roles and responsibilities of the BS Process Leader in order to successfully lead the project.

03. Define Problem: Too often, projects encounter issues when the problem is poorly defined or understood.

04. Identify Stakeholders: The BSPL identifies and describes several key stakeholder roles that are essential to the project’s success so they can find the best candidates for those positions on the team.

05. Current Evidence: The lynchpin of the BS process is based on the ability to compile evidence to make decisions.

06. Attitudes Matter: Provide an understanding of the importance of understanding the customer/employee’s perspective in the BS process and how to collect that information.

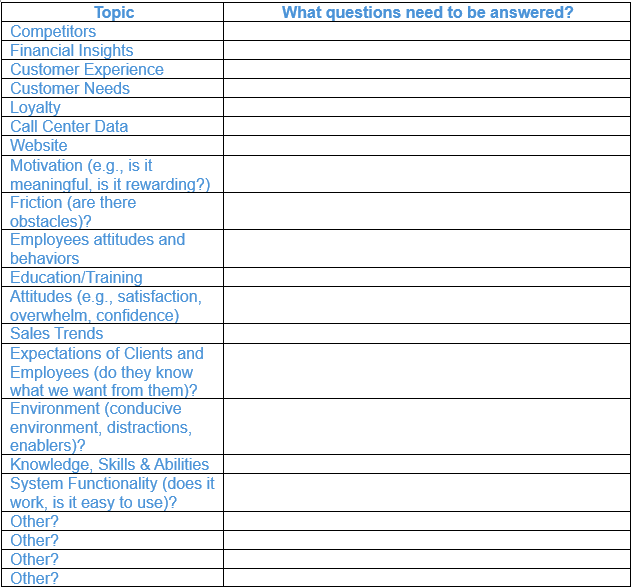

07. Research Agenda: The primary object of this session is to help the BSPL set a research agenda for the project by prioritizing data needs.

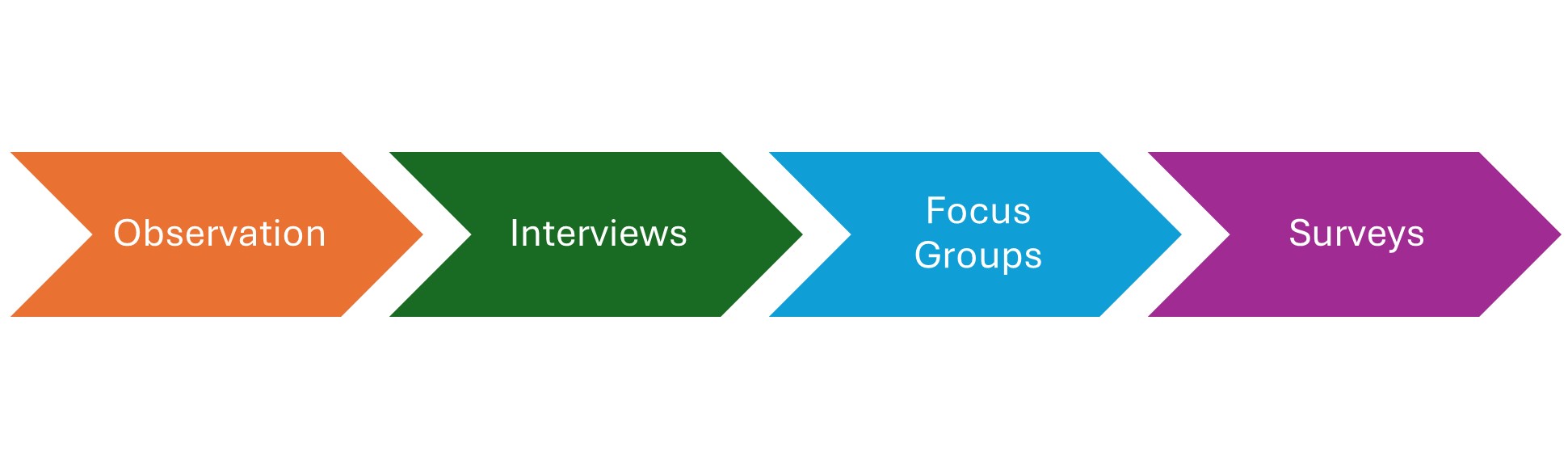

08. Collecting Evidence: This manual provides important information about several of the key data collection methods available for collecting qualitative data (observation, interviews, and focus groups) in order to help the BSPL pick the best method for the project.

09. Analyze Insights: Prepare the BSPL for effective analysis of data and reporting. In addition, it introduces the most popular and highly impactful tool – the survey.

10. Engage Stakeholders: Since stakeholders are very busy and have various different needs, interests, and motivations, the BSPL needs to understand how to keep them engaged with the project.

11. Selling Science: Prepare BSPL to introduce and describe the BS Process in a compelling and influential way.

12. Synthesize Plans: Help the BSPL put the project in perspective by pulling up after working through the various phases of planning and allowing them to reflect on their own attitudes about the process.

Strategies

01. Clarify several important elements of planning (e.g., risk assessment, communication methods and tools, and gaining an understanding of what has worked best in the past).

02. Review each of the seven core responsibilities of the BSPL in detail to clarify the expectations of the BSPL.

03. This section clarifies the importance of BSPL’s role in understanding the problem. We provide a process for defining the problem, along with sample problem statements. The BSPL will take the first shot at defining the problem statement. It also provides instructions on how to carry out the task.

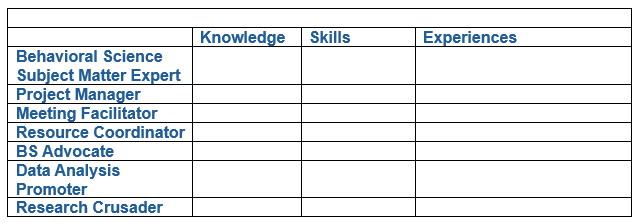

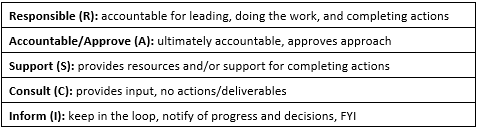

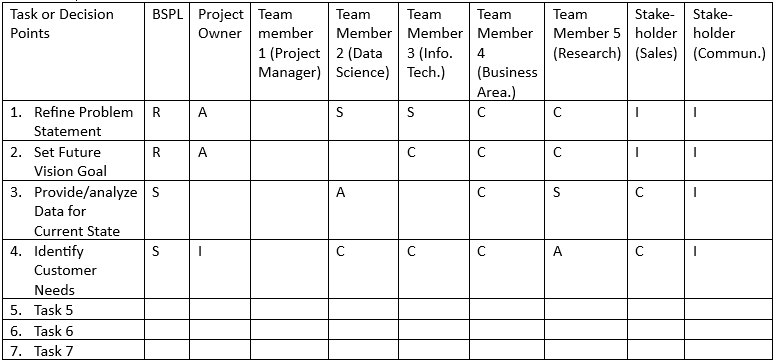

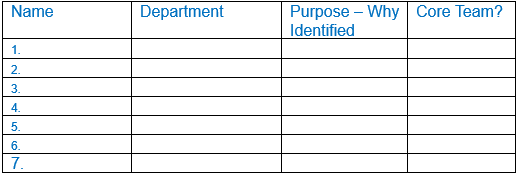

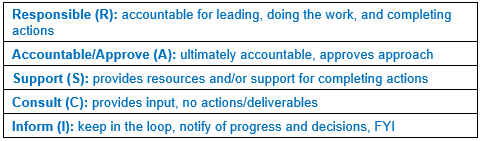

04. We describe each key role, along with the knowledge and skills required. We also provide some alternative team member options. Finally, a tool for clarifying roles and responsibilities is offered as a best practice.

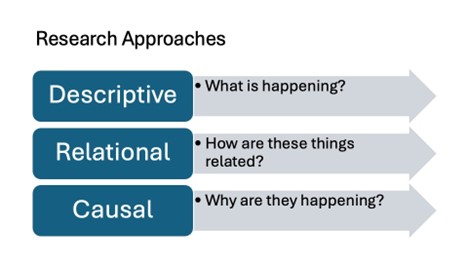

05. This manual identifies and describes evidence the BSPL needs to collect. It also provides information about the value of quantitative and qualitative data in the BS process.

06. Outlines a process for collecting qualitative data about target audience’s behaviors, interests, needs, perspectives and intentions.

07. Introduce a process to capture and then systematically rate the research needs of the project in order to prioritize the most critical. In addition, learn how to identify the characteristic of the sample of the target audience.

08. The pros, cons, and best practices for three key qualitative data collections methods (observation, interviewing, and focus groups) are outlined. In addition, recommendations for procedural best practices are provided to prepare the BSPL and team.

09. Outline the pros, cons, and best practices for surveys to help BSPLs validate assumptions and data collected with small sample using other tools. Also provides instruction on analyzing and reporting on research.

10. Outlines best practices and BS principles that will increase engagement of stakeholders. This starts in the planning phase and first contact.

11. Strategies for introducing BS to stakeholders are reviewed as well as BS principles that will support stakeholder commitment to the project.

12. Also acknowledge 2 BS principles that may apply to the BSPL personally and address.

Tasks

01. Identify key milestones. Build the first draft of a project plan.

02. Identify strengths and opportunities for development related to the key responsibilities. Identify stakeholders who can complement your skills where there may be gaps.

03. Collect preliminary, existing data related to the problem.

04. Develop the first draft of the problem statement.

05. Fill the key stakeholder jobs. Clarify responsibilities for each of the stakeholders.

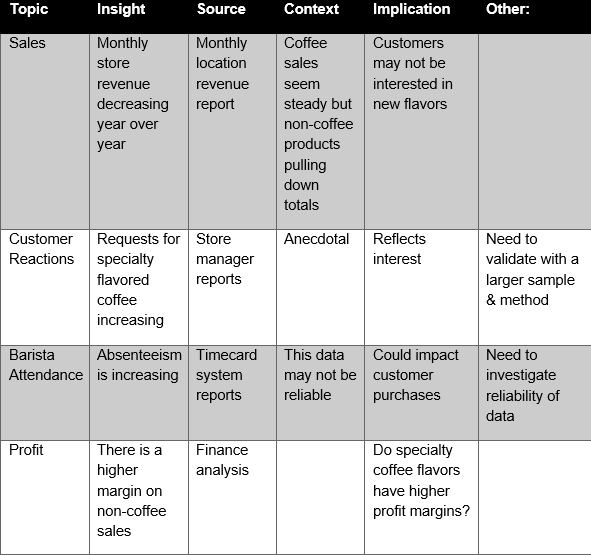

06. Collect, record, and track evidence relevant to the challenge. Similarly, compile and log unanswered questions.

07. Determine a preliminary plan for collecting data. Develop a recruiting message for collecting data from customers and employees.

08. Select a data collection methodology. Establish the research agenda by prioritizing the research needs.

09. Finalize decisions on data collection methods and draft survey questions as needed.

10. Draft the initial invitation for stakeholders to meet to discuss the project. Draft the agenda for the initial meeting.

11. Develop messaging, definitions, and a story for discussing BS with stakeholders.

12. Create a to do list, work with other BSPLs in the company to develop some of the information and tools needed to proceed. Land on a project.

Introduction

The first module in the Behavioral Science Corporate program is called Successful Planning. It focuses on helping the BSPL set the stage and prepare for leading a project that delivers extraordinary results. This module will assist the BSPL in establishing a solid foundation and successfully initiating the project.

This introduction will cover the following topics:

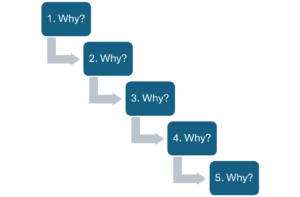

1. What do we mean by planning?

2. What’s the current state of planning, and why is it so important?

3. Why it’s important to focus on planning in the BS approach

4. Why planning is important

5. What BS has to offer that makes planning more effective

6. What does the planning module cover?

7. BS cases around planning

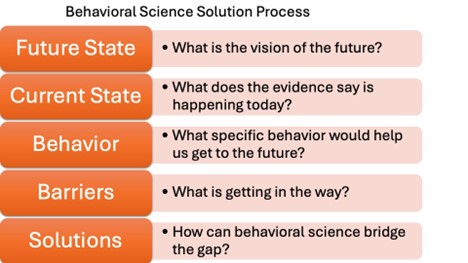

Planning simply involves considering the necessary tasks and organizing them before beginning the actual work. It involves considering the end goal, determining the steps needed to reach the goal, diagnosing the problem, identifying the resources needed to complete the steps (e.g., time, people, tools, and data), the enablers to the process (e.g., communication methods, team processes, and dynamics), barriers to success, and then creating a framework to enable the process to work as effectively as possible.

This is where you cross the T’s and dot the I’s. It’s where the scope of the project is laid out, where the timeline, costs, deliverables, and details are ironed out. We set expectations and identify assumptions at this stage. Before roles are assigned and the team starts working on the plan, project planning entails a thorough mapping and arrangement of the project’s objectives, tasks, schedules, and resources. As you can see, there is some complexity and discipline involved in this kind of work.

Before we get into the specifics of the connection between BS and planning, it would be helpful to share some information on the abysmal current state of planning in general.

Current Position

• According to the Project Management Institute, organizations were wasting an average of $97 million for every $1 billion invested due to poor project performance.

• Thirty-seven percent of projects fail because leaders don’t define project objectives and milestones clearly.

(Source: Click Here)

• 80% of organizations report that they spend at least half their time on rework. (Source: Geneca)

• When team leads don’t effectively manage requirements, 47 percent of projects fail to hit their targets.

(Source: Click Here)

• 38% of companies believe that the greatest barriers to success are confusion about team roles and responsibilities. (Source: Geneca)

The first point of connection to BS pertains to the type of work involved in planning. Planning requires us to take time to stop and think, to look ahead, to anticipate obstacles, to consider needs, different paths to get work done, potential skills, and people who might be able to help. It requires us to make some estimates about needs and resources, align resources to those needs, and organize all of that information in a way that is easy to understand and follow. Just making that list feels like a lot of work.

As humans, most of us resist this type of complex thinking involved in planning. We prefer fast, action-oriented, and easy-to-do work. For most people, the kind of work we can do automatically without thinking is preferred over work that requires consideration, contemplation, and deliberation.

However, implementing a BS process in your company will require you to move the organization toward a deeper way of thinking, a different way of operating, a new way of tackling problems, and developing solutions. This begins with planning. In fact, you can think of planning as a kind of microcosm of BS.

As you get started on your projects, one of the first things the BSPL must do is create a plan. Now for those of you who are familiar with planning may think that this is pretty basic, right? If you are already a skilled planner, great, you’ll have a jump start on applying your knowledge and experience with planning to the BS process. However, even those who are expert planners, will learn about planning is applied somewhat differently in the BS process. The following paragraphs will describe more about that. Now this may not seem like the most exciting content, but there’s more than meets the eye in this section.

BS is a different animal:

On many other kinds of projects, building a good project plan can be quick and easy. However, in the BS process, the job of planning will be much more complex and more of a drawn-out process. This is because the challenges you will tackle in the BS realm are likely to be deeper and more multi-faceted. Consider the name BS, science is not something that evolves quickly. Scientists think about what factors impact outcomes, they do research to test hypotheses, and they analyze results. When they don’t get the results they expected, they go back to the drawing board. There is nothing fast about science.

Keep in mind that as a BSPL, you are leveraging real science. Understanding and influencing human behavior is not fast or easy, but it will yield extraordinary results. The diagnosis process will be more comprehensive, the identification of barriers and potential solutions will all be broader and more complex. Because BS is different, we can’t overstate enough the importance of planning.

You are introducing a new process.

Because BS is more complex, the process involved is more involved and requires a more disciplined approach to solve these meaty challenges. As humans we all resist change, and as was mentioned earlier, we also resist complex thinking. Since resistance to any new process is naturally higher, it makes the stakes involved in getting it right even more important.

Great results are the payoff. As you are aware, you are leveraging BS as a way to get superior results. So, you want the process to be as beneficial as possible and deliver on the promise of achieving a different kind of outcome. As the leader of the project, you have a significant stake in making sure it is effective and delivers great results for your company. Following the BS process is crucial for your success. Like any process, there are many places where the work can go off the rails, so to speak. Planning is one of the key factors in ensuring a successful project. It may not be the most enjoyable component of managing projects, but it is the most vital part of reducing risk and failure rates.

Accelerate adoption of BS. The BS process will likely continue to be considered “new” for a long time after you get many projects completed. Change takes time, and your organization will need time to acclimate to the new process. This process will most likely be much different from your company’s typical method of solving problems. The company’s acceptance of the process will be faster if stakeholders like it and see positive results from its use. Planning is a key factor in ensuring the project goes well. As the BS advocate in your company, you’ll want the stakeholders involved in the project to be excited about how it works and about the different results that come from the BS process. In order to have the BS approach gain a foothold in your company, and be in demand, you’ll want the best results possible, which will only be possible with careful and thorough planning.

The BSPL’s success. As the BSPL, you will be in the spotlight, working on applying the Behavioral Science approach to your projects. If the project is successful, it will be personally rewarding and will reflect well on you as a leader. Team members will appreciate being a part of a well-organized and well-led process. They will be more helpful during the process and will want to work with you again on future projects. Of course, this could have a positive impact on your job performance and future career prospects.

As the BSPL, you’ll learn about the various roles you have in leading this important work. It will take some time to build knowledge, experience, and confidence. Careful planning can help you feel more confident faster. It allows you to think ahead to each phase in the process and mentally rehearse and prepare for what is ahead to avoid surprises. This is especially critical as you are learning and growing your BS acumen.

Applying the BS approach to planning: The Successful Planning Module

The first module, Successful Planning, guides participants through the whys and hows needed to take the necessary steps to establish a successful project. Planning is often an overlooked but extremely critical part of a BS project.

Roles and Stakeholders: During this workshop, participants will gain an understanding of their role as the process leader, the roles of other stakeholders, and best practices for engaging with their stakeholders. As was mentioned previously, there is great benefit from having an effective working team and from them having a positive experience. This module’s sections and tools will greatly assist you in guiding them through the process and ensuring their successful engagement.

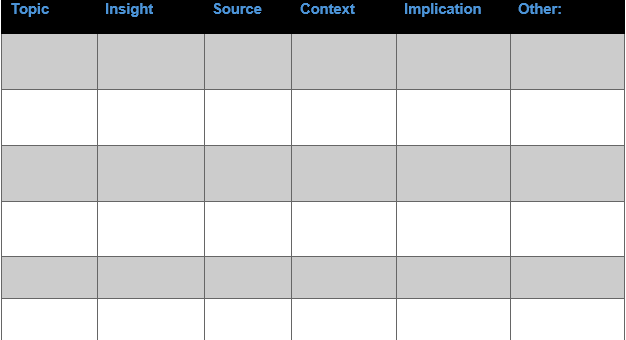

Planning Tools: In order to effectively prepare, the module will introduce several key planning tools. Even if you are a skilled planner, you’ll hear about how these tools apply specifically to the BS process. These tools include, for example, an insight collection template, a data collection prioritization tool, RASCI charts, and sample timelines.

Evidence-Based: More importantly, this module provides a foundation for the basic components of data collection, analysis, and reporting. Getting a head start on data collection is a vital ingredient for facilitating a successful project. In addition, the planning process includes several sections on data and experimentation. The BS approach plays a crucial role in 1) data-based decision-making, 2) learning through testing, and 3) experimenting. In fact, these are core elements of every BS process. This module includes a strong grounding in the core principles of data collection and lays a foundation for setting a research agenda for the project. This work is critical to begin in the planning phase because data collection often takes time. Having the data collected, analyzed, and available to help make decisions in later phases of the project will be important.

BS Acumen: Additionally, the BSPL will gain an understanding of eight BS principles to utilize during the planning process. This will help the BSPL start building the BS subject matter expertise needed to lead others in the organization. This module also includes twelve case studies to help understand how other companies have used the BS principles to get better results and to help participants apply the principles they are learning.

Intro to Benefits and BS

Below are some of the basic benefits of planning. After considering the list, you may wonder why so many organizations fail at planning or why they rush through this important step. That is where BS comes in to help understand what isn’t working. As the leader of the BS process, it will be critical that you don’t fall victim to some of these challenges.

Why is planning so important?

1. Performance increases with planning.

With careful project preparation, you can prevent the issues that cause projects to fail. Without this vital step, it is almost certain things will fall through the cracks, and a project team is bound to miss crucial details, deadlines, and eventually deliverables. Planning, when done well, lowers expenses, conserves resources, and enhances workplace morale and company culture. A successful project will be your reward if your planning process is accurate and focused. Process leaders, project owners, teams, sponsors, and stakeholders all greatly benefit from project planning. Planning is necessary to determine desired outcomes, prevent missing deadlines, and eventually deliver the agreed-upon good, service, or outcome.

2. Reduces risk

Risk is always lurking in the background, whether at a micro or macro level. What may seem like a minor risk to a task could pose a larger threat later during project execution. Proper planning allows teams to ensure that risks can be mitigated and that smaller tasks roll up into milestones that meet the larger goals of the project, reducing potential risks.

2. Planning is cost-effective

2. Planning is cost-effective

Project failures can be costly. Even when a business completes a project successfully, they may still spend a significant amount of additional money that wasn’t necessary due to poor planning. Unexpected problems, scope creep, and delays are common in poorly designed projects. A project that steadily expands in scope (and expense) as a result of unanticipated events or modifications is known as scope creep. Project planning helps to avoid inefficient practices and activities by giving the execution stage structure and foresight. For this reason, businesses that adhere to sound project management procedures waste less time and money than those that do not.

3. It enhances group communication

Effective communication is critical to the successful completion of any project, regardless of scale or nature. Project stakeholders need to have excellent communication skills to ensure they complete project duties accurately and on schedule. Planning for effective communications between all stakeholders (leaders, team members, and those outside of the team) is essential, especially when a project includes numerous employees, teams, outsourced suppliers, and possibly even staff members in different regions or time zones. A good project plan considers the ways in which the team will communicate and identifies the best means of doing so, including chat, email, virtual meetings, shared documents, online tools, and more.

4. It ensures optimal resource utilization

4. It ensures optimal resource utilization

The BSPL is responsible for securing the resources needed for the project, including the right people with the right skills and knowledge as well as their time. Resource planning is one of the most important aspects of project planning. The utilization of resources, such as personnel, tools, funds, office space, and time, forms the foundation of every project. Ensuring that a company allocates and uses resources in the most appropriate and cost-effective manner is practically impossible without competent planning. BSPL needs to consider throughout the project how effectively to allocate not only their own time but that of others because several projects frequently compete for the same resources.

4. It helps keep all stakeholders aligned

In the BS process teamwork is essential. It is essential that all team members are aware of and understand their duties and responsibilities, how their contribution fits into the larger picture, and how their actions affect the productivity of other team members. In order to do this, the BSPL must set clear expectations for them both individually and collectively. A well-crafted plan gives all involved parties an official point of reference. In this way, everyone will agree and remain informed about duties, deadlines, expectations, and work processes. It’s even simpler for all partners to access and view the project plan at any time when you utilize project management software.

Reducing project failure rates

You may wonder why people resist planning when there are so many benefits. Or what is more likely is that people give lip service to planning, taking significant short-cuts to put only the bare minimum plans in place. There are several reasons.

1. Unrealistic time pressures. Unrealistic expectations have plagued many project managers. The pressure to complete a project in a specified amount of time can create situations where people skip or rush through the planning process.

2. Negative emotion. As was mentioned earlier, the planning work is difficult, and many find it unpleasant. In addition, some people may feel less confident in their planning abilities, so move out of this phase as quickly as possible.

3. Not rewarded. Organizations often reward results rather than planning. So people are motivated to move quickly toward results. However, BSPL should be encouraged to go slow at first and go faster later. Spending more time up front will pay off with significant, high-quality results at the end of a project. If you doubt that this is true, look at the statistics at the beginning of the introduction.

4. Impatience. This can play a significant role in why BSPLs gloss over the planning phase and jump right into execution. This desire to skip over the most critical project management phase will likely result in regret and rework, at the very least.

5. Lack of understanding. Not understanding how planning affects the successful execution of projects may be one of the biggest reasons planning is ignored.

There are several BS principles that align with some planning best practices. For example, breaking things down to make them more achievable is a BS principle. Best practices in planning include breaking projects into major steps or milestones.

Tips for increasing your value and effectiveness

To become an expert at planning, work on anticipating all aspects of a project that will either create a win or risk the outcome. First, determine if the project aligns with broader business objectives. If not, a more thorough review of the project is necessary. There will be situations where a project is still required in order to address an isolated problem that may not necessarily be part of the bigger strategic picture.

Future State

Can BS really make a difference in the world? If history is a reliable indicator of the future, yes, it can. Due to its enormous potential to make significant advancements and improvements in a wide variety of situations in a vast number of important ways, interest in it has increased significantly in the past decade. In response, organizations all around the world—including governments, corporations, and healthcare organizations—have set up behavioral science departments.

In the field of BS, our approach to problem-solving is both incredibly effective, and yet presents a significant challenge. Today, we rely on existing data to diagnose and understand behavioral challenges. While the emphasis on rigorous evidence-based diagnosis and solutions is great, it may also result in an over-reliance on the past. Behavioral scientists should be particularly sensitive to the proliferation of artificial intelligence in this regard. While this can be an incredibly powerful tool, we need to heed the warning about depending too heavily on evidence and data that reflect our history, not our future.

Today, BS is used to “fix” products, services, and tools that aren’t working. We are asked to help “nudge” people in the right direction to overcome barriers or shortcomings in the systems. However, a better approach is for BS to get involved in the forefront of building the products, tools, and systems without noise or obstacles to behavior rather than “nudging” behavior in the right direction after the fact.

Research has shown that brief, focused treatments can effectively modify behavior. Simple solutions can be attractive, but there are risks involved if we can’t balance them with the complexity of the real world. These solutions may become ineffective or less successful than anticipated when settings change quickly. We need to build muscle, tools, and processes to support solving more complex problems with BS solutions.

The global COVID-19 pandemic is a good example of the complexity of challenges we have not faced in the past. Countless challenges emerged during that timeframe, with really important consequences. For example, how do we encourage people to wash their hands and wear masks, how do we slow the rapid expansion of misinformation and encourage people to think critically about that information, and how do we help people work collaboratively remotely? Behavioral Science is well positioned to offer solutions but has not been tested for answering these types of complex problems. While the field did not solve these issues in a significant way, there is hope for the future. The BS process included in this program will move closer to answering fairly complex problems in your organization.

In order to be successful handling these mega problems, it will be necessary to challenge our assumptions about how interventions and solutions function inside of larger systems. It has been suggested by some experts that part of the answer to moving BS forward is to leverage some of the very planning tools we have been talking about in this introduction. For example, a process for behavioral planning could be used to test hypotheses about how people would behave in different environments and situations, and leverage scenario testing to gain insights about what happens. This could be accomplished by looking at several future state scenarios to see how interventions might play out in a corporate environment or in various customer situations. This research could offer guideposts and direction for building more stable, more scalable, longer-term solutions to more complex problems.

Behavioral designers need to be able to identify changes over time, navigate complicated system dynamics, and move away from oversimplified conceptions of success. Below are two case studies that accentuate the power of planning in the BS process.

Case Study 1

Source: Click Here

Part 1

Plan-making has also been shown to alter important health behaviors. Consider two large-scale plan-making field experiments conducted in collaboration with Evive Health, a company that sends the employees of its client corporations reminder mailings when they are due to receive immunizations and medical exams.

The first experiment involved encouraging employees to receive flu shots (Milkman, Beshears, Choi, Laibson, & Madrian, 2011). Seasonal influenza leads to more than 30,000 hospitalizations and more than 25,000 deaths in the United States each year (Thompson et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 2009). However, the frequency of these adverse incidents could be greatly reduced by increasing influenza vaccination rates – flu shots are widely available, inexpensive, and effective.

Thousands of employees from a Mid- western company received mailings encouraging them to receive free flu shots, which were offered at a variety of on-site work clinics. Each mailing provided details about the date(s), time(s) and location of the clinic relevant to the employee to whom it was addressed.

Employees were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions. Those in a control condition received a mailing with only the personalized clinic information described above; those in the plan-making condition also received a prompt to make a plan by writing down the date and time when they intended to attend a clinic – in a box printed on the mailing.

Clinic attendance sheets were used to track the receipt of flu shots.

This subtle plan-making prompt costlessly increased flu shot uptake from 33 percent of targets in the control condition to 37 percent in the plan- making condition.

Further analysis revealed that the prompt was most effective for the subset of employees whose on-site flu shot clinics were only open for a single day, as opposed to three or five days. For this population there was little margin for error – the window of opportunity to receive a flu shot was fleeting, making failure to follow through especially costly. In this subpopulation, the planning prompt increased flu shot take-up from 30% to 38%, suggesting that plan-making interventions may be most potent when there is a narrow window of opportunity for achieving a given goal.

Part 2

In the second experiment with Evive, thousands of employees overdue for a colonoscopy received a mailing encouraging them to receive this procedure (Beshears, Choi, Laibson, Madrian, & Milkman, 2011). Colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States, resulting in approximately 50,000 fatalities per year, and 38% of these deaths could be prevented each year if all those advised to receive colonoscopies complied.

The mailings provided personalized details about the cost of a colonoscopy and how to schedule an appointment. They also included a yellow sticky note affixed to the top right-hand corner, which recipients were prompted to use as a reminder to schedule and keep their colonoscopy appointment. For those randomly assigned to the plan-making condition, this yellow note also included a plan-making prompt with blank lines on which employees could write down when and with whom their colonoscopy appointment would take place.

Those randomly assigned to a control condition, the yellow note was blank. Approximately seven months after these reminders were mailed,

6.2% of employees who received the control mailing had received a colonoscopy, while 7.2% of employees who received the plan-making mailing had received a colonoscopy.

Increasing colonoscopy take-up from 6.2% to 7.2% would be expected to save 271 life-years for every 100,000 people who national guidelines indicate should receive a colonoscopy (Zauber et al., 2008). Further, the plan-making mailer’s impact was most potent among the sub-populations predicted to be the most at risk of forgetfulness, populations like older adults and those who did not comply with previous reminders.

Case Study 2

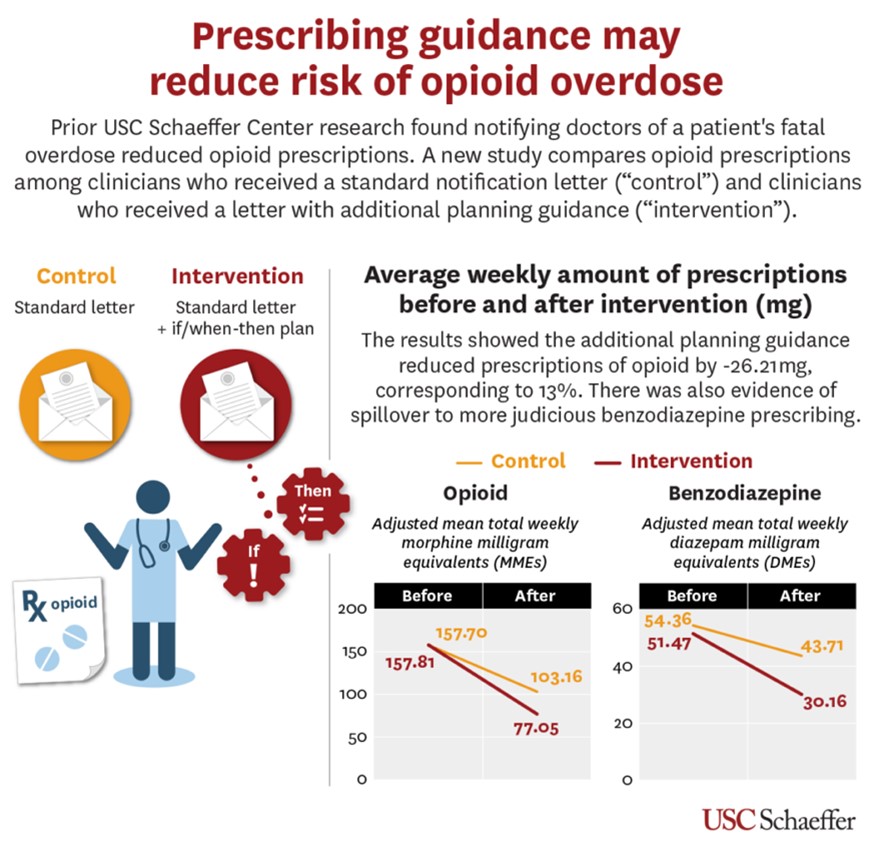

Source: Want Safer Prescribing? Provide Doctors with a Plan for Helping Patients in Pain

By USC Schaeffer Center. January 12, 2024

Physicians who are notified that a patient has died of a drug overdose are more judicious in issuing controlled substances if the notification includes a plan for what to do during subsequent patient visits, according to a study published today in Nature Communications.

Compared to a letter with demonstrated effectiveness at improving prescribing safety, physicians who received notifications with additional planning guidance reduced prescriptions of opioids by nearly 13%. They also reduced prescriptions of the anxiety medications benzodiazepines by more than 8%. Together these drugs constitute the bulk of prescription drug overdoses.

The results suggest that the guidance, known as if/when planning prompts, may lower risks to patients by reducing the intensity and frequency of these prescriptions. The findings also indicate that letters notifying a physician that a patient has fatally overdosed are more effective when they include the guidance prompts.

The letter with planning prompts asked the doctor to carry out a specific plan: “When your next patient presents with pain, keep… [these] … recommendations close at hand to assist with their safe care. Also, be comfortable voicing your concern about prescribing safety with them so that they are also aware of the dangers associated with scheduled drugs.”

“Providing physicians a simple plan that will guide them at a patient visit appears to help temper their use of these drugs,” said Jason Doctor, lead author of the study and co-director of the Behavioral Sciences Program at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics.

“This represents a promising approach to reducing fatal drug overdoses, one that is both affordable and scalable.”

The study builds on two previous ones conducted by Doctor and his colleagues. The first one found that physicians reduced opioid prescriptions by 10% in the three months following notification of a fatal overdose. A second study found that physicians reduced opioid prescriptions by 7% one year after receiving notification. The letter used in these previous studies served as the control in this study.

“This latest study is part of an evolution toward better understanding how to enact behavior change among physicians whose patients have suffered negative consequences from care by the medical community,” said Doctor, who is also chair of the Department of Health Policy and Management at the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy.

The latest randomized study involved sending letters to 541 clinicians in Los Angeles County: 284 received a standard letter notifying them that a patient had died of an overdose; 257 received a letter with the additional guidance.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Start Planning

Planning for the success of your project is a critically important step to fully leverage the benefits of the BS process, and this manual will guide you through some initial stages of the process. You’ll learn about how the BS approach can be applied to virtually all of the human-centered challenges in your organization. In this section, you’ll gain a better understanding of how to create a repeatable BS process in your organization.

This section will provide guidance on key success factors, such as identifying risks and being flexible. You’ll also get some practical examples around major milestones, typical timreframes, and establishing a timeline for your project. Considerations will also include alignment with other parts of your organization’s eco-system (e.g., budgeting, strategic planning, information technology enhancements, R&D cycles, etc.). This section will equip you with the necessary foundation to initiate a successful program!

Chapter 2: Process Leader

As the owner of the BS process, the BSPL has a critical role to play and will assume multiple responsibilities. They will be the BS subject matter expert, project leader, facilitator, resource coordinator, research crusader, and advocate for the process. The work of each of these roles and their responsibilities will be highlighted.

This chapter will include a discussion of the knowledge and skills needed for success as a BS PL. Additional considerations, such as leveraging a co-leader and sharing responsibility with the business area for outcomes and results, will also be covered.

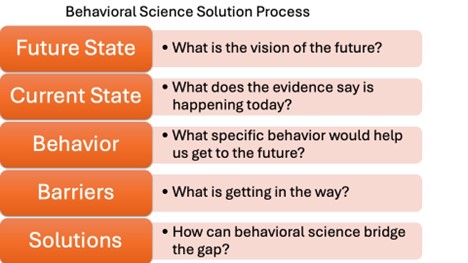

Chapter 3: Define Problem

In the BS process, the project leader is responsible for defining the problem. While the problem may seem straightforward, it is rarely as simple as it looks. As the project leader, you’ll need to gain a fairly thorough understanding of the problem, context, history, current results, user experience, and the business’ perspectives on what is not working as expected. At this stage in the process, data will be broadly defined to include not only traditional types of numeric data such as revenue, sales projections, call volume, or statistical analyses, but also more anecdotal data such as stakeholder beliefs about what is needed, what is working, and what isn’t working. There will be opportunities later in the process to test these assumptions, but at this point, it’s critically important to get these perceptions on the table.

In this section, you’ll be introduced to tools to help with the problem definition process as well as a framework for writing a problem statement. In addition, you’ll have access to examples of problem statements and have a chance to try out the process of writing a problem statement of your own.

Chapter 4: Identify Stakeholders

The Behavioral Science process and methodology work best in a collaborative manner. This chapter will dive into explaining why others are needed to make the process work effectively, how to identify the appropriate stakeholders, and determining the ideal set of roles needed for the project. Since every organization and every BS project are different, you’ll learn how to put the right team together for each project.

In this process, there is room for stakeholders to have different levels of involvement in different phases. This section outlines different roles and options to meet the needs of the stakeholders and process. This section will review best practices such as how to assemble the best teams, plan for the appropriate team size, and match stakeholders to specific parts of the project.

Chapter 5: Current Evidence

Collecting data for evidence-based decision making is a fundamental part of the BS process. As the BS project leader, you will informally collect some readily available data to develop the Problem Statement. You’ll learn about best practices for collecting and tracking this data.

However, at this point in the process, you will need to get serious about collecting data around important questions that remain unanswered. This section will assist you in starting to record crucial questions that require data-driven answers. For example, it is highly likely that you will need to collect some specific user experience data (if it doesn’t already exist).

Chapter 6: Attitudes Matter

While quantitative data is vital to helping us understand our business challenges, in the realm of BS, understanding “softer” data (e.g., people’s thoughts, emotions, attitudes, and reactions) is a primary focus. These are places we can influence desired behavior with BS tactics.

This section will discuss the importance of deeply understanding your customers and employees. This section will cover some of the primary methods of data collection and analysis. This section will also introduce you to some best practices and standardized methods for recruiting customers and employees to participate in your research studies.

Chapter 7: Research Agenda

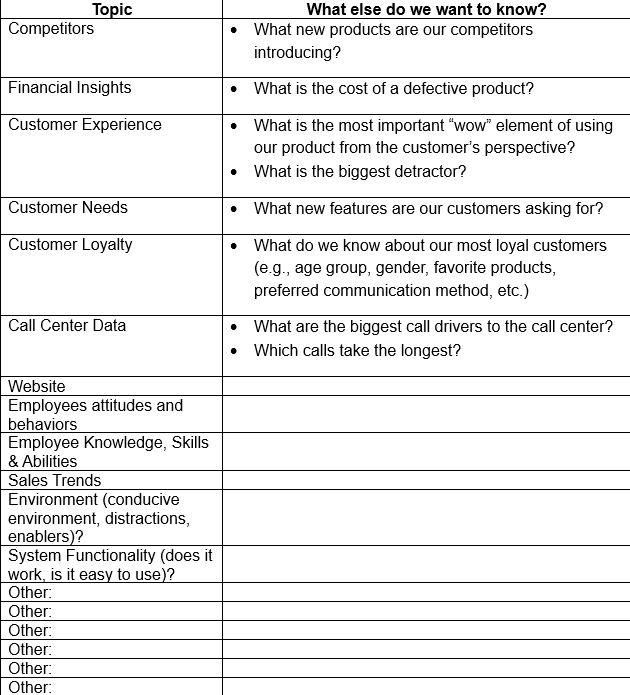

As you begin your project, you’ll identify many important questions you and your team want to know in order to effectively diagnose your challenge. In most cases, you’ll have more questions than you can practically collect data for. This section will help you prioritize those questions so you can begin to develop a research agenda (i.e., a plan and schedule for research efforts). This is included in the planning phase of the projects, so you can launch these studies to have data available for later steps in the process.

This chapter will also help you learn to identify the appropriate target audience for the research (i.e., your sample). We will review research concepts like oversampling, representative samples, and randomization to provide you with the necessary information to collaborate with the data scientists and researchers involved in your project.

Chapter 8: Collect Insights

In this section, you’ll learn about the various tools for collecting insights (e.g., focus groups, interviews, and observations). These methods are outlined in detail, including the pros, cons, and best practices, in order to support your ability to start collecting insights from your target audience.

You’ll also be guided through the specific steps and tips needed to help you systematically and objectively better understand your customers and employees.

Chapter 9: Analyze Insights

This manual will focus on one of the most important data collection tools: the survey. We will cover best practices, risks, and recommendations for overcoming survey problems, such as survey fatigue and response bias. You’ll also be introduced to important concepts, such as pilot testing, prior to launching a large-scale survey.

The second part of this manual will cover analyzing the data collected. Depending on the type of analysis needed and the resources available in your organization, you may need to coordinate some of the data collection with other groups. You’ll be introduced to some best practices for this type of collaboration. Finally, the section will wrap up with recommendations for presenting and communicating the results of the data in a compelling and informative way.

Chapter 10: Engage Stakeholders

A large part of the project leader’s role is to create conditions and an environment where the project team and stakeholders will thrive. Your stakeholders are busy people with competing perspectives, interests, and agendas. Your ability to garner their support will be critical to the project. Fortunately, many of the BS principles can help influence strong engagement from the players involved.

The section will include strategies to influence stakeholders, considerations for diversity and inclusion, and how to deal with situations such as conflict and stakeholders exiting and entering projects. While this step is primarily about engaging stakeholders and garnering support, it is also a great opportunity to collect information from stakeholders, and understand their interests, motivations, and agendas.

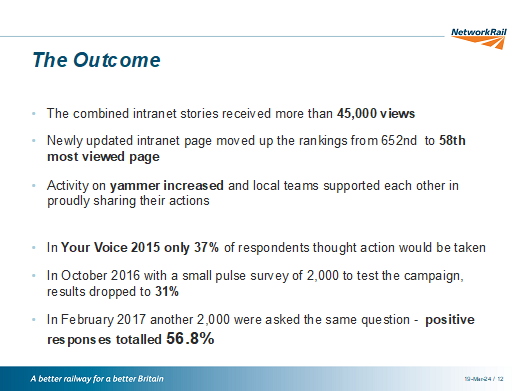

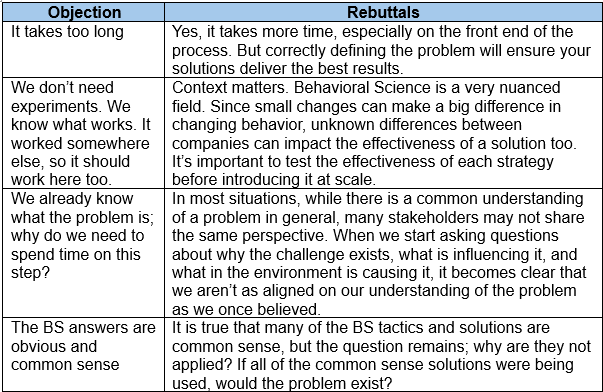

Chapter 11: Selling Science

As a new process in your organization, you’ll need to lay the groundwork for introducing the BS concept, process, and approach to your stakeholders. Given the size and scope of the BS field, explaining it to your stakeholders will not be easy. For example, some of your stakeholders will want to know about the business case and hear about proven results from other companies. Others will be interested in the data and experimentation aspects. Still, others will want to hear about the innovative solutions. In addition, just like any new process, you’ll encounter some skeptics and resistance to change. This section will provide ideas and recommendations for handling objections. This section will walk you through suggestions for talking about BS in a way that is compelling, will pique their interest, and will garner their interest.

Chapter 12: Next Steps

The last section in the module helps to bring the planning phase into focus by stepping back and looking at each of the pieces as a whole. We will briefly review each of the module’s covered areas and include a list of follow-up items to complete before the next session. The session will also help participants identify a great project to start with if they haven’t already done so.

At this point in the process, the BSPLs may find themselves subject to a couple of BS principles (fight-flight and overconfidence). These principles provide an excellent opportunity to demonstrate BS in real time with real examples. Finally, recommendations are offered to maintain a mindset of resilience and flexibility as the process proceeds.

Curriculum

Behavioral Science – Workshop 1 – Successful Planning

- Start Planning

- Process Leader

- Define Problem

- Identify Stakeholders

- Current Evidence

- Attitudes Matter

- Research Agenda

- Collect Insights

- Analyze Insights

- Engage Stakeholders

- Selling Science

- Next Steps

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Behavioral Science corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast

As a guide, the Appleton Greene Behavioral Science corporate training program should take 12-18 months to complete, depending upon your availability and current commitments. The reason why there is such a variance in time estimates is because every student is an individual, with differing productivity levels and different commitments. These differentiations are then exaggerated by the fact that this is a distance-learning program, which incorporates the practical integration of academic theory as an as a part of the training program. Consequently all of the project studies are real, which means that important decisions and compromises need to be made. You will want to get things right and will need to be patient with your expectations in order to ensure that they are. We would always recommend that you are prudent with your own task and time forecasts, but you still need to develop them and have a clear indication of what are realistic expectations in your case. With reference to your time planning: consider the time that you can realistically dedicate towards study with the program every week; calculate how long it should take you to complete the program, using the guidelines featured here; then break the program down into logical modules and allocate a suitable proportion of time to each of them, these will be your milestones; you can create a time plan by using a spreadsheet on your computer, or a personal organizer such as MS Outlook, you could also use a financial forecasting software; break your time forecasts down into manageable chunks of time, the more specific you can be, the more productive and accurate your time management will be; finally, use formulas where possible to do your time calculations for you, because this will help later on when your forecasts need to change in line with actual performance. With reference to your task planning: refer to your list of tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve your program objectives; with reference to your time plan, calculate when each task should be implemented; remember that you are not estimating when your objectives will be achieved, but when you will need to focus upon implementing the corresponding tasks; you also need to ensure that each task is implemented in conjunction with the associated training modules which are relevant; then break each single task down into a list of specific to do’s, say approximately ten to do’s for each task and enter these into your study plan; once again you could use MS Outlook to incorporate both your time and task planning and this could constitute your study plan; you could also use a project management software like MS Project. You should now have a clear and realistic forecast detailing when you can expect to be able to do something about undertaking the tasks to achieve your program objectives.

Performance management

It is one thing to develop your study forecast, it is quite another to monitor your progress. Ultimately it is less important whether you achieve your original study forecast and more important that you update it so that it constantly remains realistic in line with your performance. As you begin to work through the program, you will begin to have more of an idea about your own personal performance and productivity levels as a distance-learner. Once you have completed your first study module, you should re-evaluate your study forecast for both time and tasks, so that they reflect your actual performance level achieved. In order to achieve this you must first time yourself while training by using an alarm clock. Set the alarm for hourly intervals and make a note of how far you have come within that time. You can then make a note of your actual performance on your study plan and then compare your performance against your forecast. Then consider the reasons that have contributed towards your performance level, whether they are positive or negative and make a considered adjustment to your future forecasts as a result. Given time, you should start achieving your forecasts regularly.

With reference to time management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual time taken in your study plan; consider your successes with time-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; consider your failures with time-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to time planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your time expectations. You need to be consistent with your time management, otherwise you will never complete your studies. This will either be because you are not contributing enough time to your studies, or you will become less efficient with the time that you do allocate to your studies. Remember, if you are not in control of your studies, they can just become yet another cause of stress for you.

With reference to your task management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual tasks that you have undertaken in your study plan; consider your successes with task-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case; take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; consider your failures with task-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to task planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your task expectations. You need to be consistent with your task management, otherwise you will never know whether you are achieving your program objectives or not.

Keeping in touch

You will have access to qualified and experienced professors and tutors who are responsible for providing tutorial support for your particular training program. So don’t be shy about letting them know how you are getting on. We keep electronic records of all tutorial support emails so that professors and tutors can review previous correspondence before considering an individual response. It also means that there is a record of all communications between you and your professors and tutors and this helps to avoid any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation. If you have a problem relating to the program, share it with them via email. It is likely that they have come across the same problem before and are usually able to make helpful suggestions and steer you in the right direction. To learn more about when and how to use tutorial support, please refer to the Tutorial Support section of this student information guide. This will help you to ensure that you are making the most of tutorial support that is available to you and will ultimately contribute towards your success and enjoyment with your training program.

Work colleagues and family

You should certainly discuss your program study progress with your colleagues, friends and your family. Appleton Greene training programs are very practical. They require you to seek information from other people, to plan, develop and implement processes with other people and to achieve feedback from other people in relation to viability and productivity. You will therefore have plenty of opportunities to test your ideas and enlist the views of others. People tend to be sympathetic towards distance-learners, so don’t bottle it all up in yourself. Get out there and share it! It is also likely that your family and colleagues are going to benefit from your labors with the program, so they are likely to be much more interested in being involved than you might think. Be bold about delegating work to those who might benefit themselves. This is a great way to achieve understanding and commitment from people who you may later rely upon for process implementation. Share your experiences with your friends and family.

Making it relevant

The key to successful learning is to make it relevant to your own individual circumstances. At all times you should be trying to make bridges between the content of the program and your own situation. Whether you achieve this through quiet reflection or through interactive discussion with your colleagues, client partners or your family, remember that it is the most important and rewarding aspect of translating your studies into real self-improvement. You should be clear about how you want the program to benefit you. This involves setting clear study objectives in relation to the content of the course in terms of understanding, concepts, completing research or reviewing activities and relating the content of the modules to your own situation. Your objectives may understandably change as you work through the program, in which case you should enter the revised objectives on your study plan so that you have a permanent reminder of what you are trying to achieve, when and why.

Distance-learning check-list

Prepare your study environment, your study tools and rules.

Undertake detailed self-assessment in terms of your ability as a learner.

Create a format for your study plan.

Consider your study objectives and tasks.

Create a study forecast.

Assess your study performance.

Re-evaluate your study forecast.

Be consistent when managing your study plan.

Use your Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) for tutorial support.

Make sure you keep in touch with those around you.

Tutorial Support

Programs

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. They are implemented over a sustainable period of time and professional support is consistently provided by qualified learning providers and specialist consultants.

Support available

You will have a designated Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and an Accredited Consultant and we encourage you to communicate with them as much as possible. In all cases tutorial support is provided online because we can then keep a record of all communications to ensure that tutorial support remains consistent. You would also be forwarding your work to the tutorial support unit for evaluation and assessment. You will receive individual feedback on all of the work that you undertake on a one-to-one basis, together with specific recommendations for anything that may need to be changed in order to achieve a pass with merit or a pass with distinction and you then have as many opportunities as you may need to re-submit project studies until they meet with the required standard. Consequently the only reason that you should really fail (CLP) is if you do not do the work. It makes no difference to us whether a student takes 12 months or 18 months to complete the program, what matters is that in all cases the same quality standard will have been achieved.

Support Process

Please forward all of your future emails to the designated (CLP) Tutorial Support Unit email address that has been provided and please do not duplicate or copy your emails to other AGC email accounts as this will just cause unnecessary administration. Please note that emails are always answered as quickly as possible but you will need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general tutorial support emails during busy periods, because emails are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. You will also need to allow a period of up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Please therefore kindly allow for this within your time planning. All communications are managed online via email because it enables tutorial service support managers to review other communications which have been received before responding and it ensures that there is a copy of all communications retained on file for future reference. All communications will be stored within your personal (CLP) study file here at Appleton Greene throughout your designated study period. If you need any assistance or clarification at any time, please do not hesitate to contact us by forwarding an email and remember that we are here to help. If you have any questions, please list and number your questions succinctly and you can then be sure of receiving specific answers to each and every query.

Time Management

It takes approximately 1 Year to complete the Behavioral Science corporate training program, incorporating 12 x 6-hour monthly workshops. Each student will also need to contribute approximately 4 hours per week over 1 Year of their personal time. Students can study from home or work at their own pace and are responsible for managing their own study plan. There are no formal examinations and students are evaluated and assessed based upon their project study submissions, together with the quality of their internal analysis and supporting documents. They can contribute more time towards study when they have the time to do so and can contribute less time when they are busy. All students tend to be in full time employment while studying and the Behavioral Science program is purposely designed to accommodate this, so there is plenty of flexibility in terms of time management. It makes no difference to us at Appleton Greene, whether individuals take 12-18 months to complete this program. What matters is that in all cases the same standard of quality will have been achieved with the standard and bespoke programs that have been developed.

Distance Learning Guide

The distance learning guide should be your first port of call when starting your training program. It will help you when you are planning how and when to study, how to create the right environment and how to establish the right frame of mind. If you can lay the foundations properly during the planning stage, then it will contribute to your enjoyment and productivity while training later. The guide helps to change your lifestyle in order to accommodate time for study and to cultivate good study habits. It helps you to chart your progress so that you can measure your performance and achieve your goals. It explains the tools that you will need for study and how to make them work. It also explains how to translate academic theory into practical reality. Spend some time now working through your distance learning guide and make sure that you have firm foundations in place so that you can make the most of your distance learning program. There is no requirement for you to attend training workshops or classes at Appleton Greene offices. The entire program is undertaken online, program course manuals and project studies are administered via the Appleton Greene web site and via email, so you are able to study at your own pace and in the comfort of your own home or office as long as you have a computer and access to the internet.

How To Study

The how to study guide provides students with a clear understanding of the Appleton Greene facilitation via distance learning training methods and enables students to obtain a clear overview of the training program content. It enables students to understand the step-by-step training methods used by Appleton Greene and how course manuals are integrated with project studies. It explains the research and development that is required and the need to provide evidence and references to support your statements. It also enables students to understand precisely what will be required of them in order to achieve a pass with merit and a pass with distinction for individual project studies and provides useful guidance on how to be innovative and creative when developing your Unique Program Proposition (UPP).

Tutorial Support

Tutorial support for the Appleton Greene Behavioral Science corporate training program is provided online either through the Appleton Greene Client Support Portal (CSP), or via email. All tutorial support requests are facilitated by a designated Program Administration Manager (PAM). They are responsible for deciding which professor or tutor is the most appropriate option relating to the support required and then the tutorial support request is forwarded onto them. Once the professor or tutor has completed the tutorial support request and answered any questions that have been asked, this communication is then returned to the student via email by the designated Program Administration Manager (PAM). This enables all tutorial support, between students, professors and tutors, to be facilitated by the designated Program Administration Manager (PAM) efficiently and securely through the email account. You will therefore need to allow a period of up to 20 business days for responses to general support queries and up to 30 business days for the evaluation and assessment of project studies, because all tutorial support requests are answered strictly within the order in which they are received. This does not include weekends or public holidays. Consequently you need to put some thought into the management of your tutorial support procedure in order to ensure that your study plan is feasible and to obtain the maximum possible benefit from tutorial support during your period of study. Please retain copies of your tutorial support emails for future reference. Please ensure that ALL of your tutorial support emails are set out using the format as suggested within your guide to tutorial support. Your tutorial support emails need to be referenced clearly to the specific part of the course manual or project study which you are working on at any given time. You also need to list and number any questions that you would like to ask, up to a maximum of five questions within each tutorial support email. Remember the more specific you can be with your questions the more specific your answers will be too and this will help you to avoid any unnecessary misunderstanding, misinterpretation, or duplication. The guide to tutorial support is intended to help you to understand how and when to use support in order to ensure that you get the most out of your training program. Appleton Greene training programs are designed to enable you to do things for yourself. They provide you with a structure or a framework and we use tutorial support to facilitate students while they practically implement what they learn. In other words, we are enabling students to do things for themselves. The benefits of distance learning via facilitation are considerable and are much more sustainable in the long-term than traditional short-term knowledge sharing programs. Consequently you should learn how and when to use tutorial support so that you can maximize the benefits from your learning experience with Appleton Greene. This guide describes the purpose of each training function and how to use them and how to use tutorial support in relation to each aspect of the training program. It also provides useful tips and guidance with regard to best practice.

Tutorial Support Tips

Students are often unsure about how and when to use tutorial support with Appleton Greene. This Tip List will help you to understand more about how to achieve the most from using tutorial support. Refer to it regularly to ensure that you are continuing to use the service properly. Tutorial support is critical to the success of your training experience, but it is important to understand when and how to use it in order to maximize the benefit that you receive. It is no coincidence that those students who succeed are those that learn how to be positive, proactive and productive when using tutorial support.

Be positive and friendly with your tutorial support emails

Remember that if you forward an email to the tutorial support unit, you are dealing with real people. “Do unto others as you would expect others to do unto you”. If you are positive, complimentary and generally friendly in your emails, you will generate a similar response in return. This will be more enjoyable, productive and rewarding for you in the long-term.

Think about the impression that you want to create