Value Proposition

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Value Proposition is provided by Mr. Knowles MBA Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

Personal Profile

Mr Knowles is a Certified Learning Provider (CLP) at Appleton Greene and an acknowledged expert in the fields of business strategy, customer value, stakeholder value and the management of change. He has extensive consulting experience with a particular specialization in value proposition development for B2B companies in the manufacturing, engineering, construction, building products, financial services, healthcare devices and airline sectors. The hallmark of his work is a focus on both customer outcomes (leading to topline growth and pricing power) and business model design (leading to increased operating margins), both of which result in higher business valuations.

Mr Knowles has authored five articles in the Harvard Business Review and twelve in the MIT Sloan Management Review (six of which form “The Strategy of Change” series) as well as contributing to multiple textbooks.

British by nationality, Mr Knowles earned his MBA from INSEAD (the leading business school in Europe) and worked in multiple European countries (including the UK, France, Germany, Switzerland, Finland, and Portugal) and before moving to the US in 1999. Since then, he has lived in New York, Colorado, Arizona, Massachusetts, and Florida.

To request further information about Mr. Knowles through Appleton Greene, please Click Here.

(CLP) Programs

Appleton Greene corporate training programs are all process-driven. They are used as vehicles to implement tangible business processes within clients’ organizations, together with training, support and facilitation during the use of these processes. Corporate training programs are therefore implemented over a sustainable period of time, that is to say, between 1 year (incorporating 12 monthly workshops), and 4 years (incorporating 48 monthly workshops). Your program information guide will specify how long each program takes to complete. Each monthly workshop takes 6 hours to implement and can be undertaken either on the client’s premises, an Appleton Greene serviced office, or online via the internet. This enables clients to implement each part of their business process, before moving onto the next stage of the program and enables employees to plan their study time around their current work commitments. The result is far greater program benefit, over a more sustainable period of time and a significantly improved return on investment.

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. All (CLP) programs are implemented over a sustainable period of time, usually between 1-4 years, incorporating 12-48 monthly workshops and professional support is consistently provided during this time by qualified learning providers and where appropriate, by Accredited Consultants.

Executive summary

Value Proposition

There are only two forms of business strategy – cost leadership and differentiation. Cost leaders succeed by offering the lowest prices; differentiated companies succeed by offering unique value to a particular set of customers. Value Proposition is the process used by differentiated companies to develop, communicate and deliver their differentiation.

The financial impact of a well-defined Value Proposition cannot be over-stated. A business achieves higher sales and profits when it is the #1 choice for certain segments of the market than when it has a more generic offering that is the #2 or #3 choice across all segments. By offering a differentiated Value Proposition that its competitors are unable or unwilling to imitate, a business establishes an unassailable foothold in the market from which to selectively expand to serve other customer segments.

The goal of a Value Proposition is to articulate why specific customers are better off doing business with you rather than with your competitors. The answer is always “great value” – an attractive ratio between the benefits being offered and the price being charged. Cost leaders focus on reducing the price to the customer as their way to increase this ratio. Differentiated companies focus on increasing the benefits that can be offered to specific customer segments so as to increase their willingness to pay, while also focusing on how these benefits can be delivered cost effectively so that both the value perceived by customers and the margin achieved by the company are increased – a sustainable “win-win”.

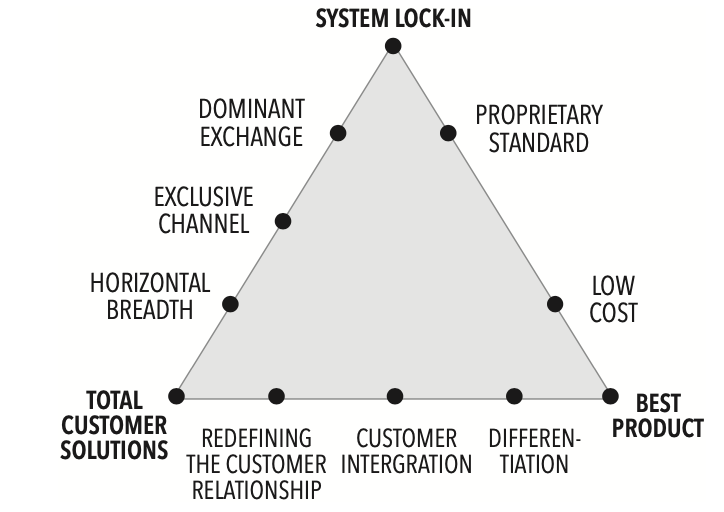

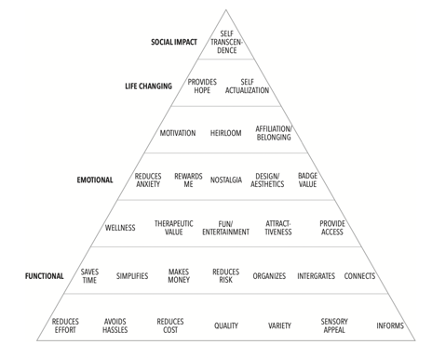

The Value Proposition program explores the many ways in which value can be created for customers (in particular, we will draw on the Hax Delta Model and the Bain Pyramid of Value) and the how the unique history, capabilities and culture of a company can be leveraged to create a Value Proposition that cannot be imitated by competitors.

Value Proposition is the discipline that transforms your sales and marketing efforts from being “a hammer looking for nails” exercise into a disciplined process for identifying and attracting those customers with whom a long-lasting and mutually beneficial commercial relationship can be created. Adopting the mindset that “not all sales dollars are created equal” means that you avoid the indiscriminate onboarding of unsuitable customers whose diversity of needs makes it impossible for your business to satisfy, leading to customer attrition and unfavorable reviews for your business.

The core objective of this program is to provide a common framework and process for companies to implement so that each of their product and service lines can identify the markets and customer segments where they are best placed to deliver distinctive value, allowing them to grow profitably, to gain market share and to sustain premium pricing.

Preview of some of the key frameworks to be covered in the program:

The objective of Value Proposition:

Contrasting the consumer and producer concept of value

The Hax Delta Model of differentiation opportunities

The Bain pyramid of customer value

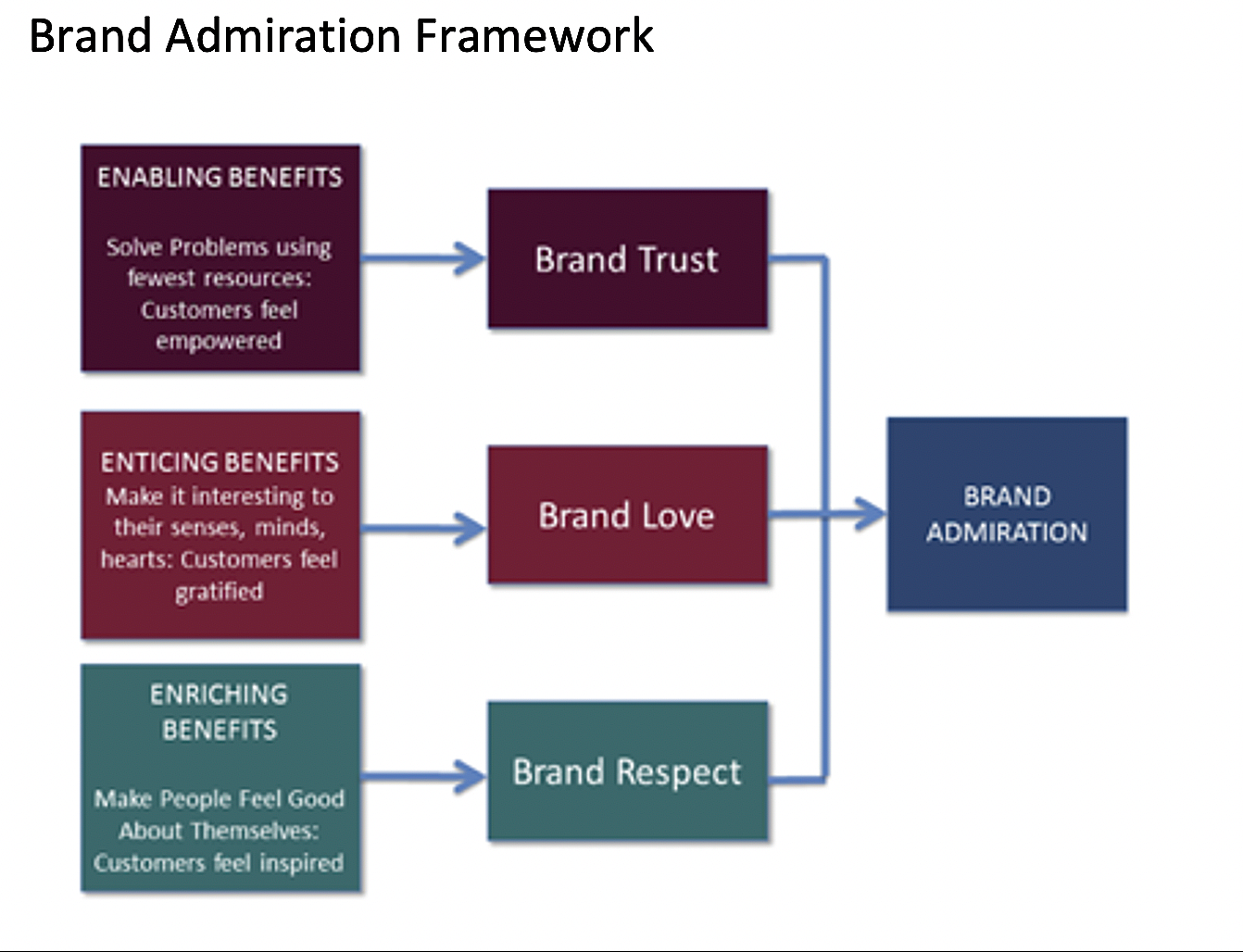

Creating strong brands that enable, entice and enrich

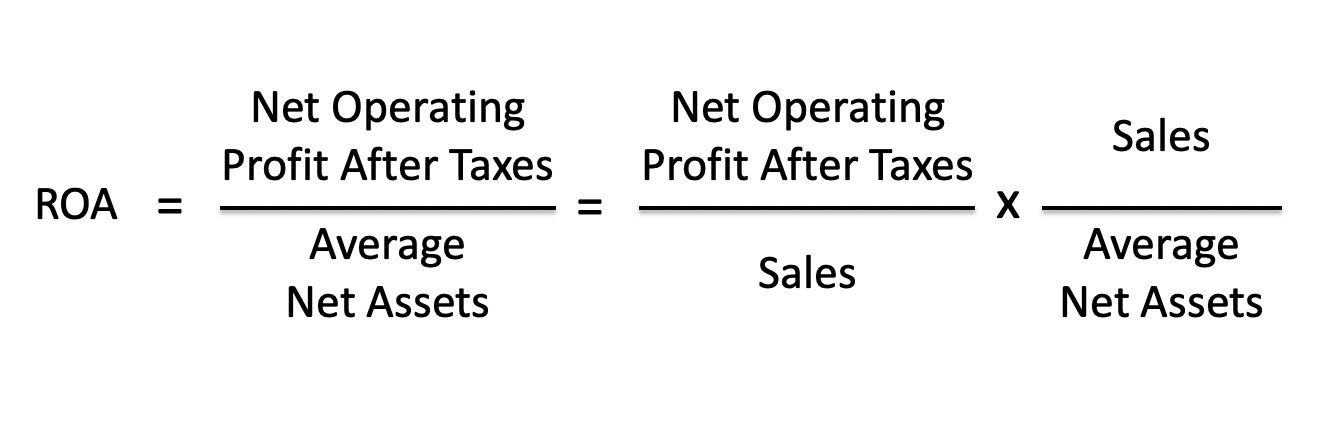

Understanding how to enhance the operating returns of the business

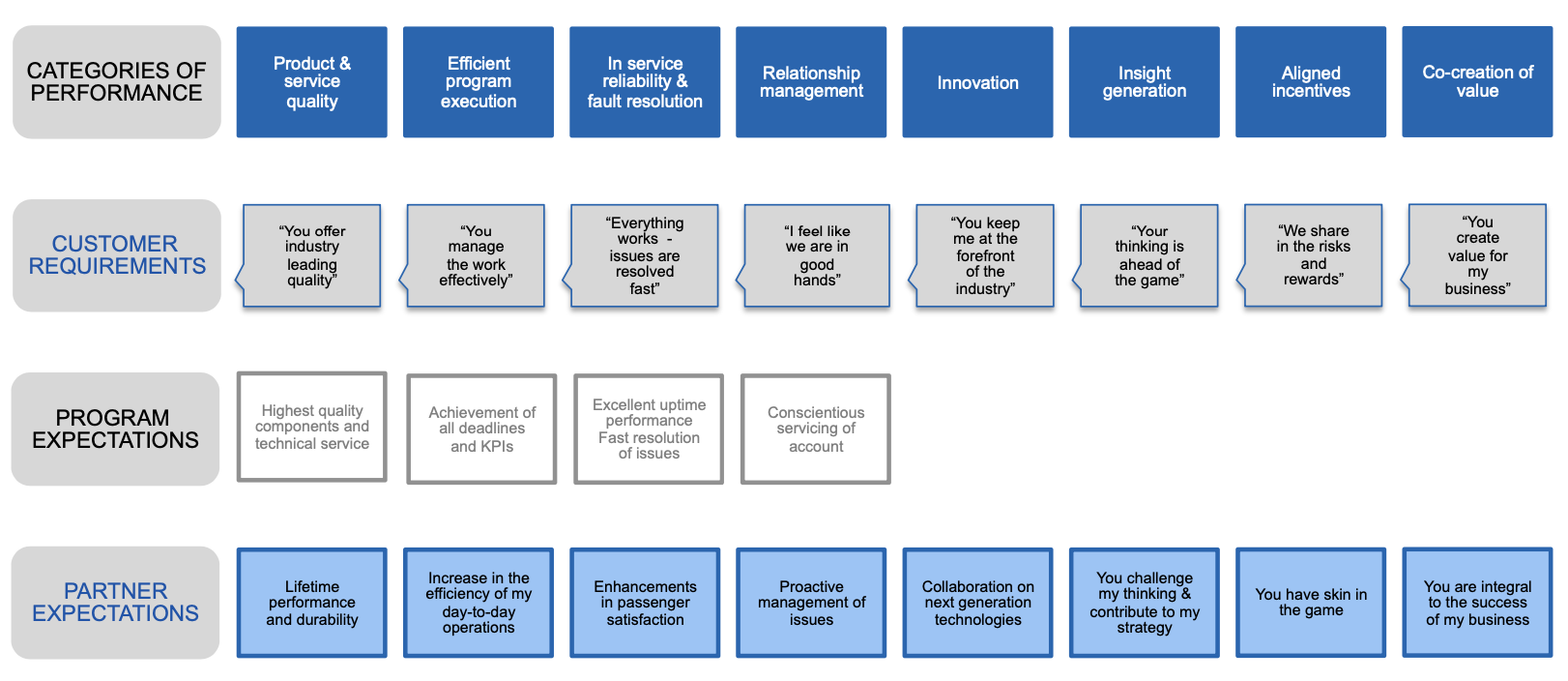

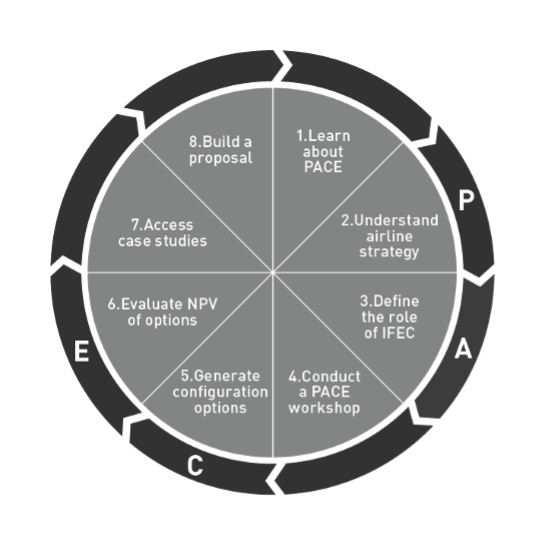

As part of the program, we will reference the Value Proposition frameworks that Mr Knowles developed for clients in financial services (for a well-known asset management and asset servicing company in Boston), in industrial construction (for a large Engineering, Procurement and Construction [EPC] company in Texas), in In Flight Entertainment & Connectivity (for the leading provider of these solutions to commercial airlines), and in medical products (for a provider of pre-surgical skin preparation products).

Categorizing the ways in which value is created for customers:

Process design for co-creating value (airline example):

Curriculum

Value Proposition – Part 1- Year 1

- Part 1 Month 1 Introduction to Value Proposition

- Part 1 Month 2 Customer Value Analysis

- Part 1 Month 3 Quantitative Research Techniques

- Part 1 Month 4 Qualitative Research Techniques

- Part 1 Month 5 Methodologies for Competitive Analysis

- Part 1 Month 6 Benchmarking Competitors

- Part 1 Month 7 Value Pools

- Part 1 Month 8 Internal Capabilities

- Part 1 Month 9 Management Systems

- Part 1 Month 10 Value Proposition Development

- Part 1 Month 11 Communicating Value

- Part 1 Month 12 Sustained Value Delivery

Program Objectives

The following list represents the Key Program Objectives (KPO) for the Appleton Greene Value Proposition corporate training program.

Value Proposition – Part 1- Year 1

Part 1 Month 1 – Introduction to Value Proposition

Objective: Establish a strong foundational understanding of value

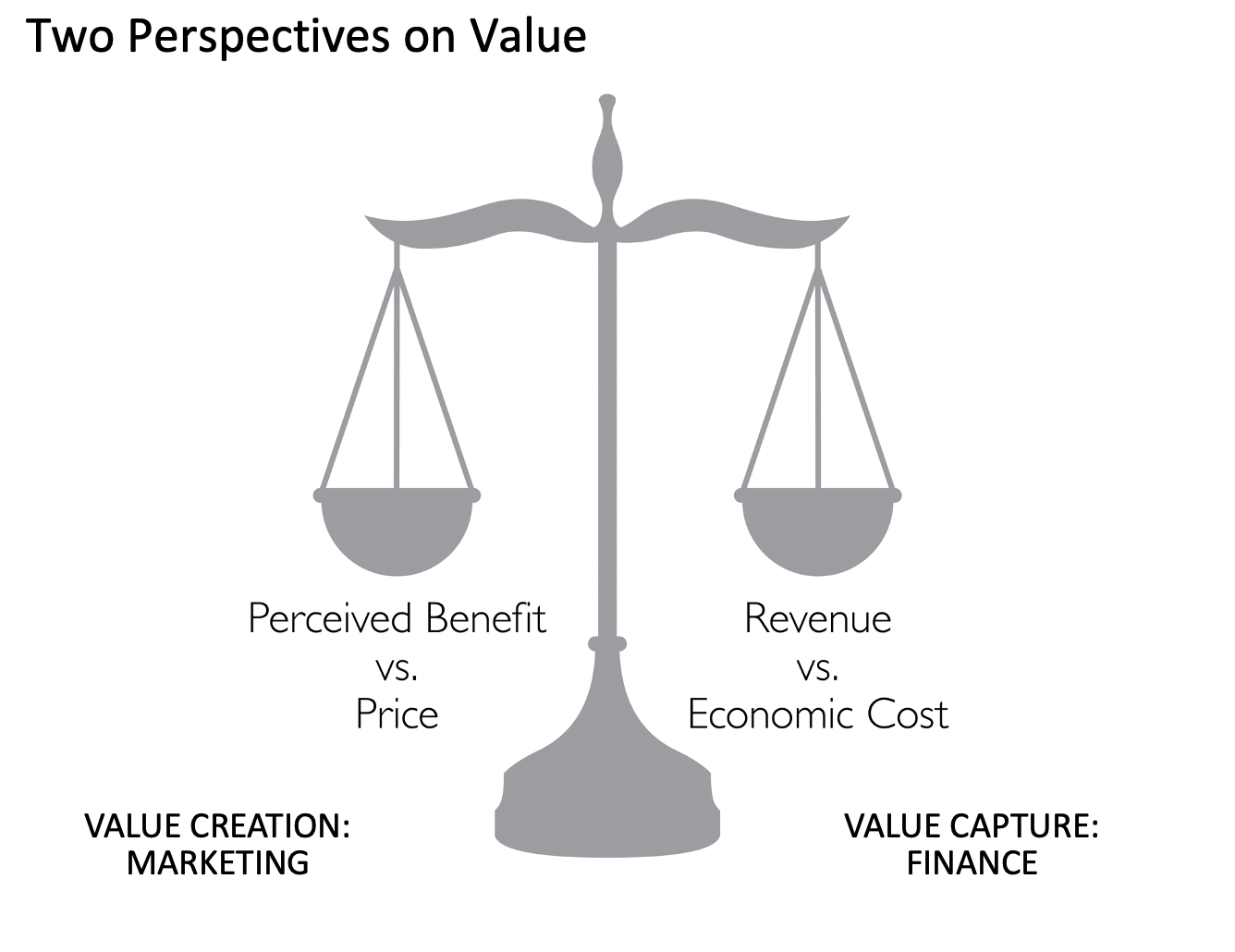

The initial workshop will focus on the fundamentals of value analysis, beginning with how value is always the ratio between a “give” and a “get”. We will explore how the concept of value changes depending on whether you are the customer or the provider and how this gives rise to two business disciplines – customer value that focuses on maximizing the benefits as perceived by the purchaser (customer value); and business model design that focuses on how to deliver this value in the most efficient and flexible way (producer value).

We will establish a solid understanding that customer value is the result of an attractive ratio between the benefits being offered and the price being charged. Cost leaders focus on reducing the price to the customer as their way to increase this ratio. Differentiated companies focus on increasing the benefits that can be offered to specific customer segments so as to increase their willingness to pay, while also focusing on how these benefits can be delivered cost effectively so that both the value perceived by customers and the margin achieved by the company are increased.

This will set the scene for an exploration of the multiple ways in which value can be created for customers either through the generation of additional benefit/revenue or the elimination of pain/cost. We will reference a number of leading frameworks (Jobs To Be Done; Business Model Canvas; Brand Admiration) to create the approach that will work best in your context.

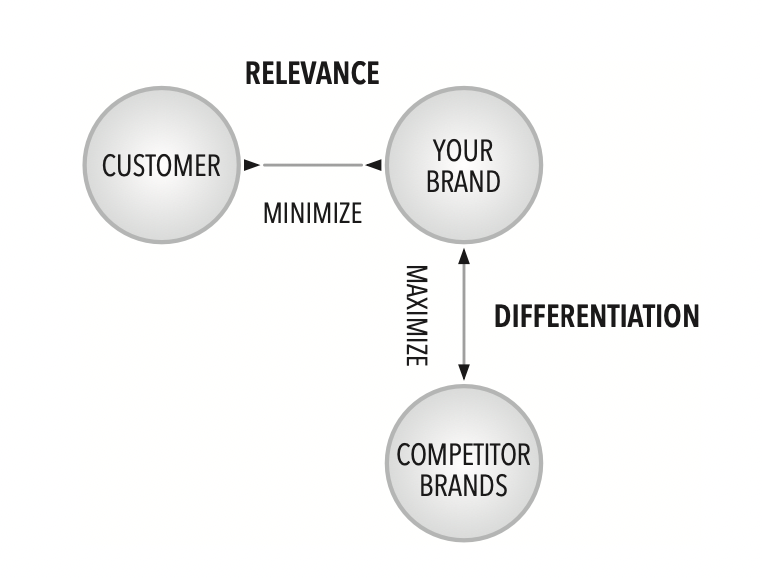

This initial workshop will conclude with a review of the improved business performance that can be generated by an effective Value Proposition that increases the customer’s willingness to pay through a dual focus on their needs and the distinctive aspects of your business. We use the framework from “The Mind of the Strategist” by Kenichi Ohmae and see how this focus on Relevance and Differentiation explains the enduring success of companies.

We explore why this focus on differentiated value is vital for business success – a business achieves higher sales and profits when it is the #1 choice for certain segments of the market versus the #2 or #3 choice in all segments.

Part 1 Month 2 – Customer value analysis

Objective: Learn the process for doing customer value analysis

In this second workshop we focus on how customers perceive and receive value, guided by Peter Drucker’s astute observation that “what customers value is always a utility – that is, what the product or service does for them”.

We discuss the multiple forms that value can take, drawing on the classification created by Bain & Co of the 30 sources of value for B2C consumers and 40 sources of value for B2B customers. We then consider how these needs typically are clustered so that, in every market, segments can be observed and how these give rise to the “generic” strategy options – initially two (Michael Porter’s cost leadership vs. differentiation) then expanded to three (Treacy & Wiersema) and then to eight strategic options (Hax’s Delta model).

We then explore how to use the Jobs To Be Done framework (Clayton Christensen/Tony Ullwick) and the Business Model Canvas (Alex Osterwalder/Yves Pigneur) to map customer needs in terms of the Jobs to be Done; Desired Outcomes; Gains/Pains; and Emotions that are desired/to be avoided.

Now that we have established a clear process for doing customer value analysis, we conclude with a discussion of the danger of “solutions” and how these are mostly defined in terms of what the producer offers rather than what the customer needs. We introduce the concept of “customer outcomes” as a superior construct that focuses on the utility that the customer is trying to derive and use this as the basis for an initial discussion of innovation. We review and the emergence of the Customer Success role within many industries.

Part 1 Month 3 – Quantitative research techniques

Objective: Learn how quantitative research tools are used to understand customers

Developing an effective go-to-market strategy relies on good information about how the needs of customers differ from one segment of the market to the other. We begin with an overview of the major research techniques that can be used to identify the basis for customer preference and discuss the merits of quantitative vs. qualitative approaches and the circumstances in which each should be used.

This month’s workshop focuses on the process for conducting quantitative research with the goal of developing customer segmentation based on demographics, psychographics and behavioral data.

We will explore MaxDiff as a powerful technique for establishing the rank order of customer preferences at the industry level and the use of Factor Structuring to use variations in these preferences as the basis for defining different customer segments.

We also review Correspondence Mapping as a visualization technique for illustrating these segments and how relevant different competitors are to each segment.

Having established a strong process for collecting and analyzing quantitative information to create an effective approach to segmentation, we will discuss the advantages of pairing quantitative and qualitative research (the latter to be covered in Month 4’s workshop). Quantitative techniques are powerful for establishing averages and identifying the basis on which segments differ, making them a vital tool for market sizing and for understanding what will appeal to the average consumer. But their reliance on “big data” means that quantitative techniques largely ignore the outliers in the data and therefore provide limited insight into how the market is changing and where innovation efforts might best be directed. This will be the focus of the Month 4 workshop.

Part 1 Month 4 – Qualitative research techniques

Objective: Learn how ethnographic techniques are used to understand customers

In this month we look at the role of “small data” as the essential basis for customer insight. We revisit the Jobs to be Done framework initially discussed in Month 2 and use this to discuss the types of information that are desirable when your goal is to serve customers that do not fit well into the segments created by the “big data” techniques covered on Month 3’s workshop.

We begin from Henry Ford’s astute observation that “if I had asked customers what they wanted, they would have said they wanted a faster horse” to discuss the challenge of developing a Value Proposition based on a product that does not yet exist – or for an audience segment that is emerging and not yet identified using quantitative techniques.

We review the research options that for developing an understanding of what the needs of customers truly are (which they may be unable to articulate – as per Henry Ford) and to establish the points of pain/inconvenience associated with existing product offerings. We will contrast the immersive, ethnographic technique used by the CPG companies to understand the daily lives of individual consumers versus traditional focus group methodologies versus newer “social listening” technologies for deriving what customers care about based on their participation in online groups and forums.

We will conclude with establishing the process by which your company can purposefully tap into the insights by “small data” to inform the Value Proposition process and new product development.

Part 1 Month 5 – Methodologies for competitive analysis

Objective: Develop the process for understanding the choice set from the customer’s POV

Strategy is about understanding the relationship between the customer, your company and competitors (the 3Cs of strategy). The previous two workshops focused on understanding customer needs and how to make your Value Proposition as relevant to customers as possible. The next two workshops address the techniques of competitive analysis so you can make your Value Proposition as differentiated as possible from those of competitors.

We will cover the two main disciplines involved in competitive analysis – one that sees competition primarily in terms of the battle for customer attention (how companies can increase their “mental and physical availability” among target customers) while the other focuses on the evaluation of the capabilities of each competitor (“benchmarking”).

This month’s workshop focuses on the dynamics of competing for customer attention and how this draws as much on altering the perceptions of what is important/relevant as much as changing the actual capabilities required to compete.

We will explore the extent to which your company and its competitors have similar knowledge of the market and similar capabilities, leading to the implication that business success often relies on “turning a difference of degree into a difference in kind” – accentuating the perceived importance of relatively minor differences between rival product offerings. We will compare and contrast the different dimensions on which competition occurs (price point; service level; distribution strategy; Job To Be Done) and use these insights to develop the process for determining how our Value Proposition should be based on the unique intersection between our capabilities, customer needs, and competitor offerings.

Part 1 Month 6 – Benchmarking competitors

Objective: Establish the process for understanding what competitors won’t or can’t do

Value Proposition is the discipline of establishing, communicating and delivering something that delivers differentiated value to a specific set of customers. As we discussed in the Month 1 and 5 workshops, there are three main parties involved – you, the customer, and competitors. In Month 5 we discussed how competition occurs in terms of positioning – what “permission” each company enjoys in the minds of customers (we will also have discussed in Month 3 how Correspondence Mapping can be used to create a 2D image of how a market segments and which companies are best placed to serve each segment).

This month our focus is on establishing the process for understanding the competition from an internal perspective – specifically, what are the constraints on how a competitor can be expected to behave based on capabilities, culture, leadership and history?

We will cover the basic principles of game theory to identify when and how competitors are likely to respond to moves that your business makes. This will highlight the importance of making moves that competitors will be unable to respond to – either because they would be prohibitively costly; or because this would undermine their own positioning in the market.

Having established the process for understanding likely competitor reaction, we will return to the question of the extent to which our Value Proposition should be based on a technical analysis of competitive offerings (focused on answering “whose product is best?”) or should primarily focus on the outcomes that customers are seeking to achieve (“which company will best help me achieve my goals?”).

Part 1 Month 7 – Value pools

Objective: Establish the process for assessing the profit potential of different segments

This month we move from asking “is there a gap in the market that we can serve?” to the question “is there a market in this gap?” – we move from a focus on the 3Cs (company, customer, competitors) to a focus on the profit potential of each segment.

Our goal is to implement a reliable process for market sizing – identifying whether the potential segments represent a sufficiently large and potentially profitable basis on which to compete?”.

As part of this process, we will review the principles behind the theories of “disruptive innovation” and “blue ocean” strategy to understand the opportunity for value innovation and the competences required to achieve this.

Our process will incorporate the techniques for estimating the profit potential of existing product market segments plus how to assess the profit potential of offerings that do not yet exist based on how the underlying customer need is currently being met and the cost structure of the leading firms in the market.

The outcome from this workshop is the process for integrating the working done on customer needs (Months 3 and 4) and competitors (Months 5 and 6) with an analysis of expected revenue, margin and growth to come up with a prioritization of where and how to compete.

Part 1 Month 8 – Internal capabilities

Objective: Leverage the uniqueness of your situation and capabilities

Up until this point in the program, our focus has been largely external – we have analyzed what customers value, what competitors are offering, and whether there are underserved and profitable gaps in the market that we might target.

Our focus shifts internally at this point to consider how we might create a business model that can serve one of these segments supremely well. The goal of this process is to identify not just how we might serve this segment, but how to do in a distinctive way such that we establish a defensible position even when competitors decide to target the same customers.

Our process will consider the distinctive capabilities that we must have to serve this segment supremely well, and the management processes and information system needed to support these distinctive capabilities.

As part of this analysis of distinctive capabilities, we will review the relative advantages of the build versus buy versus partner approach to building these capabilities.

Part 1 Month 9 – Management systems

Objective: How to create the infrastructure that sustains your ability to be different

The role of management systems in supporting Value Proposition is often overlooked. But if differentiation is the objective, then it is vital that your information infrastructure and operating practices are designed to help you deliver this differentiation. To under the design process, we will review how different companies have created management systems that support a differentiated experience (such as the personalized “home away from home” experience offered by Four Seasons or the recommendation engines that have caused Amazon and Netflix to garner such loyalty).

We will apply this thinking in the context of your company to identify the type of information that you should gather – or not gather – in order to sustain your Value Proposition.

We will then review how you might design the management system to make it too expensive or too difficult for competitors to imitate you – including the collection of non-traditional data; the granting of unusual decision rights (such as the discretion that is granted to the staff of Danny Meyer restaurants to “make things right” when there is a problem); or an elevated resource requirement (such as the time spent by Four Seasons on recruitment)

Part 1 Month 10 – Value Proposition development

Objective: Process for articulating your strategy for winning in the market

We now have in place the four key requirements for developing and sustaining a compelling Value Proposition – a clear sense of which segment of the market we are targeting; how we will compete in ways that will be hard for competitors to imitate; what capabilities we need to have to deliver on our promise; and how we will configure our processes and information system to enable superior execution of this promise.

The focus of this workshop is on learning about the process for integrating these four components into a Value Proposition that offers compelling value to the specific customers we want to attract. As part of this, we will review the Value Proposition frameworks and processes put forward in the “Business Model Canvas” and “The Lean Startup” and “Blue Ocean Strategy”.

Part 1 Month 11 – Communicating value

Objective: Ensuring that your difference is understood and valued

Now that we have established the substance of your unique Value Proposition and the business system that supports it, this workshop focuses on the most effective ways on communicating that value to our target customers.

We will explore why “show, don’t tell” is the principle of effective communication and the circumstances under which the goal of the communication should be memorability (distinctiveness) more than cognitive persuasion (differentiation).

We cover the relative advantages of different types of media (owned, earned, paid) and different channels of communication (broadcast, out of home, online, influencer) and the evidence for the cumulative impact of multi-channel communication.

Finally, we will use the 4Ps framework as a good process guide for determining the most effective combination of factors in your Value Proposition.

In conclusion, we will discuss the final assignment – a working draft of the Value Proposition for your specific business, line of business, service offering or brand.

Part 1 Month 12 – Sustained value delivery

Objective: The process for maintaining your ability to be different

This workshop will begin with a recap on the objective of a Value Proposition (differential value to a specific segment of customers) as being to establish a defensible position in the market. We will revisit how a Value Proposition leverages sources of customer value that are meaningful to customers and hard for competitors to imitate (either because they do not have the credibility or the capabilities).

We will review the interlocking set of decisions that form a strong strategy – selection of which areas of a market to address and how; and what underlying business model and set of capabilities are required to make this sustainable over time. We will discuss the financial investments and non-financial investments (for example in internal culture or customer communities) that can be made to ensure that this advantage is maintained. We will discuss how communications and positioning are used to accentuate the perceived significance of real – but often minor – differences between providers.

Our final area of study is the process for monitoring that this Value Proposition remains relevant. We will discuss the metrics and other indicators to monitor so as to provide early warning that the power of your Value Proposition may be declining. We will conclude with the process for how to refresh your Value Proposition in ways that build on the equity already created, but update it to appeal to changing preferences.

Methodology

Value Proposition

This program will cover each of three disciplines that need to be mastered in order to develop a compelling Value Proposition, namely customer value analysis; competitor analysis; and business model design.

Customer value analysis enables you to understand the ways in which the universe of potential customers (the total market) can be divided into different segments based on their preferences and ease to serve. It is the discipline of “de-averaging” to understand the range of spectrum of viable offerings that would hold particular appeal to one or more of these segments.

Competitor analysis is the discipline of understanding the competences and culture of your competitors to identify which of the potential segments are likely to be of greatest interest to them, and how strong an offer they would be able to have.

Business model design is the discipline of looking at the internal capabilities of your own business to understand the dimensions on which you enjoy an advantage – or suffer from a disadvantage.

This program unites these three disciplines to identify where and how your business is best placed to compete. Our goal is to identify a segment of the market to whom you can offer a distinctive level of value that competitors either cannot or will not match (because it would be too expensive for them to do so). The idea is to leverage existing aspects of our own business model and continue to invest in them such that we have a Value Proposition that is unique and will secure a base level of business and glowing testimonials from customers.

Industries

This service is primarily available to the following industry sectors:

Manufacturing

Capital Goods is the largest of the 24 industry groups as defined by the GICS (Global Industry Classification Standard) and comprises the following 10 industries:

• Aerospace and Defense

• Agricultural and Farm Machinery

• Building Products

• Construction and Engineering

• Construction Machinery and Heavy Trucks

• Electrical Components and Equipment

• Heavy Electrical Equipment

• Industrial Conglomerates

• Industrial Machinery

• Trading Companies and Distributors

Globally, there are 1,850 publicly-traded Capital Goods companies with more than $50 million in revenue. They generated revenues of $5.8 trillion and $1.3 trillion in operating profits in 2020 (data is from Type 2 Consulting’s analysis of the global universe of 12,000 publicly-traded companies with more than $50 million in revenue). Of this revenue, $2.6 trillion was generated by the 536 US-based Capital Goods companies.

The challenge facing most manufacturing companies is that the widespread adoption of technology and processes such as TQM (Total Quality Management) and Six Sigma mean that, as the New York Times rightfully observed, “everything is increasingly of better quality, but everything is increasingly the same”. This means that the discipline of Value Proposition is particularly important for manufacturing companies that wish to establish their differentiation.

The “commoditization of quality” is the consequence of the adoption of digital technologies [starting with the development of Computerized Numeric Controllers (CNCs) for machine shop operations and Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) for more process-oriented operations] that have driven out unintended variance from the production process.

The second major transformation in the manufacturing industry has been the strategic importance of supply chain – both in terms of speed and resilience. Beginning with the development of Material Requirements Planning (MRP) in the early 1970s, these improvements led to the first substantial application of computers in manufacturing processes.

The increased complexity of the “technology stack” required to support a modern manufacturing operation mean that all but the very largest companies are having to decide which aspects of their operations are critical to their ability to differentiate, and those aspects of technology that should be outsourced.

This has important ramifications for hiring and the reskilling of existing employees. A tech-savvy workforce that is appreciative of some of the new approaches to process management (such as quality circles, and agile development processes) is critical to competitiveness. Cycle times for product development are being dramatically reduced through technologies such as 3-D printing and fast prototyping.

The recent disruptions to supply chains and the decreased costs differentials between offshore and domestic production locations are causing many companies to consider “reshoring” and even taking back in house aspects of their operations that they had previously offshored or outsourced. The growing importance of ESG (Environmental, Societal, Governance) considerations – specifically supply chain transparency – is also tilting the balance back towards more local, more visible supply chains.

In addition to this consumer preference for local sourcing, Governments have also recognized the impact that manufacturing has on an economy’s service sector.

The outlook for manufacturing is exciting as additional technologies such as robotics, artificial intelligence, cloud computing and the Internet of Things further transform the digital component of an industry that until 60 years ago relied almost entirely on physical machinery and human labor.

Today’s challenge is to harness the synergy between the efficiencies and standardization that technology enables and the differentiation that is only achieved via human insight and ingenuity. And to combine these in a way that represents a compelling Value Proposition to customers.

Healthcare

Healthcare represents one of 11 major industry sectors as defined by the GICS (Global Industry Classification Standard). It is divided into two main industry groups – Healthcare Equipment & Services; and Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology and Life Sciences.

• Healthcare Equipment & Services subdivides into seven industries:

• Health Care Technology

• Healthcare Distributors

• Healthcare Equipment

• Healthcare Facilities

• Healthcare Services

• Healthcare Supplies

• Managed Healthcare

Healthcare is an industry of particular importance to the US – Healthcare Equipment is the 8th largest industry group globally in terms of revenue ($2.1 trillion in sales), but the 4th largest in the US. Similarly, Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology and Life Sciences is the 14th largest industry group by revenue globally ($1.1. trillion in sales), but the 8th largest in the US.

By contrast, the United Nations International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) uses a location-based approach to the categorization of the healthcare – services delivered in hospitals, services delivered in medical and dental practices, and other human health activities. This latter category includes activities performed by nurses, physiotherapists, chiropractors, medical massage, yoga therapy, music therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and acupuncture.

Health care accounts for more than 10% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in most developed countries, and it can be a significant contributor to a country’s economy. As an economic sector, healthcare comprises the activities involved in the creation and commercialization of goods and services that aid in the maintenance and restoration of health.

Healthcare is second only to technology as the industry sector that has witnessed the greatest growth over the past 30 years. In fact, technology has been the driving force behind much of the growth in specific areas of healthcare – whether in the form of DNA sequencing that supports the development of biotechnology, to precision manufacturing’s impact on the design of medical devices and prosthetics, to remote surgeries delivered via surgical robots, to the improvement in the efficiency and consistency in healthcare provision through the digitization of patient records and the increased use of telemedicine (that accelerated rapidly during the COVID pandemic).

In addition, increased consumer access to health information via the internet and the growth in apps that allow individuals to gain a better sense of their own health – whether in terms of nutrition or fitness or genetics – has created the demand for a more collaborative approach to health management.

Healthcare companies are increasingly having to behave like consumer businesses and this makes it vital that they develop a more sophisticated approach to expressing their Value Proposition than the “trust me, I am a professional” that has been the historical default in many areas of healthcare.

For commercial healthcare entities, it is important to understand the reimbursement regime in place in each country. This comprises the three aspects of coverage, classification/coding and payments.

Coverage focuses on the process and criteria used to evaluate whether a product, service, or operation falls within a defined benefit area and is eligible for reimbursement. In the US, Medicare is the entity whose attitude to any new drug or device will determine public reimbursement and, to a large extent, reimbursement by private insurers. If Medicare does not deem a new technology to be “reasonable and essential”, the chances of it being covered by other payers are little to none.

Classifications/coding are the standardized identifiers created by organizations such as the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Hospital Association (AHA), and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and that allow insurers to recognize and process claims involving the use of a drug, device, procedure or service.

Payments are non-standardized and vary considerably by whether the reimbursement is from a public source, a private insurer or the patient themselves. For Medicare coverage, there are two options: local and national coverage policies. Because local policy must follow a national coverage choice, it is far preferable to obtain national coverage. This is not without risk, since a negative decision at the national level will preclude coverage being granted at the local level.

Fiscal and demographic pressures are likely to cause a fundamental shift in how healthcare is delivered, moving it out of hospitals and into people’s homes. This is a trend that will be enabled by consumer medical devices and by smart phone apps that may leverage individual genomic information to provide an increasingly personalized level of medicine. Success in this environment will depend on being able to define and communicate a compelling Value Proposition.

Banking & Financial Services

Financials represent one of 11 industry sectors as defined by the GICS (Global Industry Classification Standard). It is divided into three industry groups – Banks, Diversified Financials, and Insurance.

Banks are subdivided between Commercial Banks, and Thrift & Mortgage Finance. Diversified Financials are subdivided between Diversified Financial Services, Consumer Finance, and Capital Markets. Insurance is typically subdivided into P&C (Property and Casualty), Health insurance, Life Insurance and the Reinsurance industry.

The financial services industry is in the midst of a digital transformation that is likely to be as significant as the abolition of exchange controls in the 1980s (allowing for the free flow of capital across borders), the abolition of minimum commissions of stock trades in the 1990s (that vastly increased trading volumes and emergence of discount brokerages), and liberalization of cross-border banking in Europe and interstate banking (in the US).

The impact of technology has been particularly evident in payment services and asset management where fixed commissions, generous exchange rate spreads and lengthy settlement periods had generated a profitable oligopoly among incumbent institutions. It is therefore not surprising that these two sectors of the industries are the ones most frequently targeted by the new generation of fintech (financial technology) firms.

This disruption is further exacerbated by the emergence of digital currencies based on blockchain technologies that have the potential to create peer-to-peer transactions without the intermediation of traditional financial service companies (referred to as defi – decentralized finance) and that may offer certain advantages relative to fiat currencies.

Given this shifting environment, it is critical that both legacy and new financial services providers define a clear Value Proposition for their target customers.

Today’s banks must adapt to three major transformations in a context marked by more complex regulations (especially around KYC “know your customer” requirements and money laundering reporting), technology development that enables competition from non-banking entities (especially the new cohort of financial technology companies, or “FinTech”), and rapidly changing customer preferences, fueled in large part by new digital platforms (mobile, e-commerce, and social networks).

Warding off competition from FinTech providers, while delivering a customer experience that anticipates changing preferences, creates a strategic priority for Value Proposition.

Technology

Information Technology represents one of 11 industry sectors as defined by the GICS (Global Industry Classification Standard). It is divided into three industry groups – Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment, Software & Services, and Technology Hardware & Equipment.

Technology Hardware & Equipment is the 5th largest industry group by revenue globally ($2.5 trillion), and the 6th largest in the US by revenue.

Technology Hardware & Equipment subdivides into eight industries:

• Communications Equipment

• Computer Hardware

• Electronic Components

• Electronic Equipment and Instruments

• Electronic Manufacturing Services

• Office Electronics

• Technology Distributors

• Technology Hardware, Storage and Peripherals

Software & Services is the 16th largest industry group by revenue globally ($1.1 trillion), but the 3rd largest in the US by revenue and the number one by profitability.

Software & Services industry group subdivides into six industries:

• Application Software

• Data Processing and Outsourced Services

• Home Entertainment Software

• Internet Software and Services

• IT Consulting and Other Services

• Systems Software

Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment is the 19th largest industry group by revenue globally ($575 billion), but the 15th largest in the US.

Digitization and the proliferation of the business internet, the consumer internet and now the Internet of Things (IoT) have been the engines of growth across all aspects of the technology industry – semiconductors, hardware, software and services. The mobile internet has provided a further boost to these trends as countries that had lacked the infrastructure for the wired internet (ethernet) became leaders in the mobile internet (for example, China with Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent, Kenya with Mpesa).

Manufacturing of technology devices has undergone a similar transformation with the ability to physically separate design from prototyping from physical production.

Perhaps most importantly, technology has moved from being part of the infrastructure of a business to being a core enabler of its strategy. New technologies or savvy use of UI (user interface) and UX (user experience) and user data has enabled a new cohort of “digital first” companies to reimagine the customer experience across a wide range of industries (e-commerce, travel, entertainment, communications). This has resulted in the explosive growth of the Software & Services industry within the overall Technology sector.

Given this, it is vital that technology companies understand the needs and preferences of their target customers (whether B2B or B2C) and articulate the differential value that they offer. In other words, a strong Value Proposition.

Because digital transformation affects all elements of a company’s operations, a technology solutions provider must be aware of how their platforms or tools can impact all components of a client’s operations. In addition, they must have a clear understanding of the “Jobs to be Done” by the client’s customer. There is limited value in streamlining a client’s process that has limited impact on the customer experience. A clear understanding of where and how value is being created is essential if technology solutions providers are to market their services effectively.

Locations

This service is primarily available within the following locations:

Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta is the #9 metropolitan area in the US by population (5.9 million) and is home to 16 companies in the Fortune 500 (the third highest concentration for any US city), including: The Home Depot, UPS, Delta Air Lines, The Coca-Cola Company, The Southern Company, WestRock, PulteGroup, Newell brands, Veritiv, NCR, Asbury Automotive.

In addition to the above, other major employers in the Atlanta area are Emory University, Northside Hospital, Piedmont Healthcare, WellStar Health System, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, The Center for Disease Control, Publix Super Markets, The Kroger Co, AT&T, Cox Enterprises, and Marriott International.

While the historical roots of Atlanta are in railroads (and it is still an important center of operations for Norfolk Southern and CSX), the local economy is now broadly based and includes aerospace (Atlanta is Delta’s home base and the Hartsfield-Jackson airport is now the world’s busiest airport, in terms of both passenger traffic and aircraft operations), road and intramodal logistics, film and television production, media operations, professional and business services, medical services, and information technology.

Broadcasting has been an important aspect of Atlanta’s economy since Ted Turner founded the Cable News Network (CNN) and the Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) in the 1980s and Cox Enterprises, now the nation’s third-largest cable television service and the publisher of over a dozen American newspapers, moved its headquarters to the city.

Recently, Atlanta has emerged as a center for film and television production, largely because of the Georgia Entertainment Industry Investment Act, which awards qualified productions a transferable income tax credit of 20% of all in-state costs for film and television investments.

Atlanta also has the fourth-largest concentration of IT jobs in the US earning it the moniker of the “Silicon Peach” – the proximity of more than 40 colleges and universities creates a rich pool of potential recruits.

Healthcare – especially the biotechnology sector – is also an increasingly important local industry with the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention providing a high-profile healthcare “halo” for the city.

Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the #10 metropolitan area in the US by population (4.9 million) and is home to the nearly 20 companies in the Fortune 500 including General Electric, Raytheon Technologies, Wayfair, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, TJX, BJ’s Wholesale Club, Liberty Mutual, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MassMutual, Biogen, State Street, Keurig Dr Pepper, Boston Scientific, Eversource Energy, American Tower, Analog Devices.

Other major employers in the Boston area are hospitals (including Mass General, Brigham and Women’s, and Beth Israel Lahey) and the many prestigious universities (including Harvard, MIT, Boston University, Northeastern, Tufts, Brandeis, Bentley and Babson) that cater to more than 350,000 students annually.

The combination of a highly educated workforce and strong focus on scientific research have made Boston a leading location for many industries including biotechnology, healthcare, consulting and financial services. A vibrant venture capital sector has cemented Boston’s reputation as a pioneer in innovation and entrepreneurship

Five sectors represent the biggest source of local employment – Healthcare (18% of employment), educational services (13%), technical and scientific services (12%), accommodation and food services (9%) and financial services.

Boston ranks second only to New York as a major financial center – focused around asset management (Fidelity Investments), asset servicing (State Street), insurance and venture capital).

Boston’s central role in the history of the US (foundation by the Puritan colonists in 1630, the location for the Boston Tea Party of 1773 and many of the key events of the Revolutionary War of 1776) makes it a major destination for both domestic and international tourists. It is also a major host for business conventions with three sizeable venues – the Seaport World Trade Center, the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center on the South Bay waterfront and the Hynes Convention Center in the Back Bay.

Relative to its population (just under 700,000 people), Boston plays an outsize role in sports and is home to storied franchises in football (Patriots), baseball (Red Socks), basketball (Celtics) and ice hockey (Bruins).

Miami, Florida

Miami is the #7 metropolitan area in the US by population (6.2 million) and is home to five companies in the Fortune 500 – Lennar Corporation, Office Depot, World Fuel Services, AutoNation, Ryder Systems.

The largest employers in the greater Miami area are American Airlines, Precision Response Corporation, Costa Farms, Royal Caribbean, Carnival Corporation, Office Depot, Wackenhut Corp, Motorola.

Miami is the busiest cruise port in the world, one of the busiest cargo ports in the US, the gateway to Latin America and a major tourist destination in its own right because of its beaches and vibrant arts and culture. The city has the third largest skyline (over 300 high rises) in the US.

These associations often overshadow Miami’s significance as an international banking center and as a healthcare location – anchored by Jackson Memorial Hospital and the Leonard Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami.

In addition, Miami is a major center for television production, and the preeminent city in the United States for Spanish language media (70% of the population of Miami identifies as Hispanic) with Telemundo and UniMás having their headquarters in the Miami area. Miami is also a significant recording center for music, with the Sony Music Latin headquarters in the city, along with many other smaller record labels.

Other industries that are significantly represented in Miami include warehousing and stone quarrying.

Miami is also the home to the National Hurricane Center and the headquarters of the United States Southern Command, responsible for military operations in Central and South America.

New York

New York is the #1 metropolitan area in the US by population (20 million) and is home to more than fifty companies in the Fortune 500 including the following:

Banks:

• J.P. Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Bank of New York Mellon

Insurance:

• MetLife, American International Group, New York Life, Travelers

Investment and other financial services:

• BlackRock, TIAA-CREF, American Express

Communications:

• CBS, Twenty-First Century Fox, Verizon Communications

Pharmaceuticals:

• Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Consumer products:

• Colgate-Palmolive, Philip Morris International

Advertising:

• Omnicom Group

The largest employers in New York City include American Airlines, Columbia University, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Northwell Health, Nielsen, and Verizon.

New York City is a global commercial hub, a center for banking and finance, retailing, transportation, tourism, real estate, and many forms of professional services (law firms, accounting firms, consultancies, advertising and communications services). Many districts in New York City are synonymous with specific industries – such as Wall Street (finance), Madison Avenue (advertising), Fifth Avenue (luxury retailing), Broadway (theater), and, most recently, Silicon Alley (high technology). Other areas of the city still bear the titles of the legacy industries they one dominated – such as the Garment District and the Meatpacking District.

New York City has been described as “the capital of the world” due to its preeminent position as a cultural, financial, and media center, and exerts an outsized influence on popular culture, finance, commerce, entertainment, education, politics, tourism, dining, art, fashion, and sports. With many iconic landmarks, it is the most photographed city in the world.

Historically, the city has been the premier gateway for legal immigration into the US, resulting in a city that is linguistically the most diverse in the world (in the order of 800 languages being spoken by New York City Residents).

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia is the #8 metropolitan area in the US by population (6.1 million) and is home to more than a dozen companies in the Fortune 500 including AmerisourceBergen, Comcast, DuPont, Corteva, Lincoln National, Aramark, Crown Holdings, Universal Health Services, Campbell Soup, Toll Brothers, Avantor, Burlington Stores.

The largest employers in the Philadelphia area are Day & Zimmerman, The University of Pennsylvania and Health System, the Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Independence Blue Cross, The City of Philadelphia, The School District of Philadelphia, GlaxoSmithKline, Temple University, and Urban Outfitters.

The local economy focuses on financial services, health care (Philadelphia is one of the largest centers for health education and research in the US), biotechnology, information technology, trade and transportation, manufacturing, oil refining, food processing, and tourism.

Philadelphia is home to a number of sought-after universities (University of Pennsylvania, Temple, Drexel, Villanova, Bryn Mawr, Swarthmore), with over 120,000 college and university students enrolled within the city limits and close to 300,000 in the metropolitan area.

Like Boston, Philadelphia plays an outsize role in US history serving as the location for many important events – most notably the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Its role as a progressive center of American life is reflected in it being home to the nation’s first library (1731), hospital (1751), medical school (1765), national capital (1774), stock exchange (1790), zoo (1874), and business school (1881). Philadelphia was named as the first UN World Heritage City in the United States. Given this, it is unsurprising that Philadelphia is a major tourist destination.

Program Benefits

Department 1

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

Department 2

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

Department 3

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

- Two Words

Testimonials

Testimonial 1

Content here…

Testimonial 2

Content here…

Testimonial 3

Content here…

Testimonial 4

Content here…

Testimonial 5

Content here…

More detailed achievements, references and testimonials are confidentially available to clients upon request.

Client Telephone Conference (CTC)

If you have any questions or if you would like to arrange a Client Telephone Conference (CTC) to discuss this particular Unique Consulting Service Proposition (UCSP) in more detail, please CLICK HERE.