High-Performance Innovation

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for High-Performance Innovation is provided by Mr. Auriach Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 48 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

Personal Profile

Mr. Auriach has experience in strategy, process & innovation performance, and digital marketing. He holds an engineering degree in aerospace from Sup’aero University (in Toulouse, France) and a master’s degree in Business Consulting from ESCP Business School (Paris, France). Mr. Auriach has industry experience in financial services, life sciences, aerospace, digital services, law, and education. He held various management positions in western Europe, including a Partner position at Accenture from 2005 to 2013. Mr. Auriach co-authored “Pro en consulting” at Vuibert editions, in collaboration with a strategy professor from ESCP.

Mr. Auriach’s personal achievements include: creating and developing new businesses up to $100 M in revenue; leveraging undervalued assets to transform businesses; aligning collaborative digital marketing processes and strategy; improving process performance; managing innovation portfolio ; carrying out post-merger integration ; orchestrating service line-wide strategy sharing ; Optimizing management reporting processes in global organizations.

Mr. Auriach’s service skills include: strategy; blue ocean strategy; process performance; lean ; training and training engineering ; digital marketing ; business consulting : innovation management. Mr. Auriach has more than 20 years of experience in business training, at Sup’aéro / ISAE aerospace engineering university in the late 90s, ESCP Business school since 2004, as an independent provider since 2013, at Celsa Sorbonne university from 2022.

To request further information about Mr. Auriach through Appleton Greene, please Click Here.

(CLP) Programs

Appleton Greene corporate training programs are all process-driven. They are used as vehicles to implement tangible business processes within clients’ organizations, together with training, support and facilitation during the use of these processes. Corporate training programs are therefore implemented over a sustainable period of time, that is to say, between 1 year (incorporating 12 monthly workshops), and 4 years (incorporating 48 monthly workshops). Your program information guide will specify how long each program takes to complete. Each monthly workshop takes 6 hours to implement and can be undertaken either on the client’s premises, an Appleton Greene serviced office, or online via the internet. This enables clients to implement each part of their business process, before moving onto the next stage of the program and enables employees to plan their study time around their current work commitments. The result is far greater program benefit, over a more sustainable period of time and a significantly improved return on investment.

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. All (CLP) programs are implemented over a sustainable period of time, usually between 1-4 years, incorporating 12-48 monthly workshops and professional support is consistently provided during this time by qualified learning providers and where appropriate, by Accredited Consultants.

Executive summary

High-Performance Innovation

History

Innovation is one of the major levers of our evolution. It characterizes and triggers the major phases of history, from the facilitation of transport thanks to the introduction of the wheel to the management of terrestrial resources thanks to space observation, passing through the distribution of books thanks to the introduction of printing.

Each of these steps is the result of the conjunction of two phenomena: the generation of an idea and the transformation of this idea into a process deployed on a large scale. Two types of actors are systematically necessary to achieve this, innovators and transformers, researchers and industrialists, triggers, and leaders. The organizations hosting the most impactful innovations are not always the ones that benefit the most. Let us think of the founders of McDonald’s who imagined a concept with great potential and of their partner who was able to deploy it on a large scale, thus realizing this potential. Examples of this dissociation between ideation and scaling up abound: the Wright brothers and the major brands in the aeronautics industry, the creators of the concept behind Facebook and Facebook, the development of rocket propulsion and its military and space applications; but also lesser known but equally impactful devices such as ubiquitous (yet invisible to the general public) cybersecurity applications, invented by an individual and filed in the patent office by a separate organization, or exotic financial products first tested on the market by a boutique, before becoming the norm when a large bank decided to industrialize them.

Conversely, there are in history organizations capable of generating a large number of ideas, sorting them, prioritizing them and transforming them into profitable and sustainable products and services, even structuring for society as a whole. The saga of the digital revolution, at work since the invention of the microprocessor in 1971, has produced champions of high-performance innovation who have been able to maximize their gains and limit their losses. Because innovating means making mistakes, infrequently and not for long, and focusing on good ideas, more often and for much longer. Let’s think of Apple, ABC, LinkedIn or Microsoft to name just a few examples. In the entertainment industry, Pixar and Disney have developed a culture of innovation that is both very free and very structured; in reality, whenever the question of investing arises, a rational approach systematically complements the creative process. Organizations capable of achieving the symbiosis between freedom to innovate and the ability to focus on the right priorities have always come out on top, including in ultra-competitive environments.

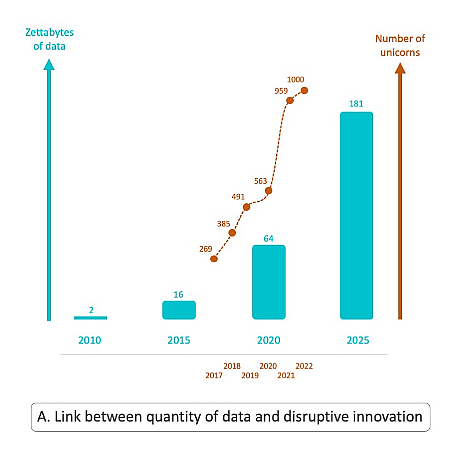

Since the end of the twentieth century, the importance taken by the control of the innovation process in the performance of companies does not stop growing. While between the end of the Second World War and the turn of the century, the key to success lay above all in a race for volumes to optimize the price-quality couple, since the end of the 1990s differentiation has been the new Grail. Why? Quite simply because thanks to the digital revolution, access to information has become rapid and general, allowing everyone to assemble the knowledge available to transform it first into a concept, then into products and services. The meta-strategy of any organization therefore consists in realizing the immense potential constituted by the knowledge of humanity, which has become deeper and more accessible than ever (see figure A below).

Current position

Nowadays, innovation has become an imposed theme of every board of directors, every institutional communication, every marketing campaign or every message addressed to staff. From this point of view, we can say that the innovation dynamic has reached a certain maturity.

Curiously, innovation is less present or unequally present at the level of customer relationship management, training, establishment and monitoring of budgets, investment, piloting, management, career management, automation, partnership management, mergers and acquisitions, benchmarking, strategic planning, or commercial action. Indeed, innovation as a major performance lever has not yet completely supplanted strategies based on the race for volume, especially since the realization of the potential of an innovation often depends on a transition to successful scale. There is therefore confusion between the old approach consisting in sustainably dominating a market thanks to its size, and a new approach consisting in managing its competitive edge by introducing new families of products and services at a sustained pace. The key difference lies in the lifespan of the product families. Although the Bic Cristal pen has been around since 1950 without any real evolution, the latest iPhone is as different from the first as a modern car can be from a Fort T. However, only a few years have passed since the introduction of the iPhone 2G on the market (in 2007).

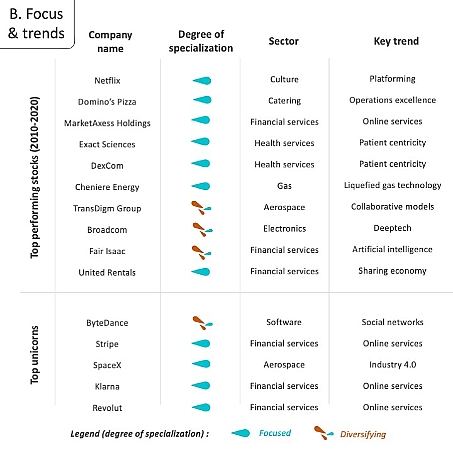

Based on this observation, it is now essential to steer your innovation process to make it both fertile and profitable, creative and rational, borrowing the best from the left brain and the right brain. This imperative is made all the more critical as the valuations of innovations measured by the statistics and forecasts in the private equity sector are melting like snow in the sun. We are witnessing a real flight to quality, a well-known phenomenon when times are uncertain or when a chronic crisis dynamic forces leaders to manage emergencies more often than they would like. What prevails for scaleups and unicorns, which are often very specialized, is also structuring for diversified companies, because all of them must innovate. Knowing how to sort and stimulate, measure and encourage, choose and finance, decide and support is at the heart of the performance of the company of our time (see figure B below).

By pushing this logic to the limit, an ideal model emerges. It takes up certain characteristics of historical models, such as the matrix organization of General Electric, or the cellular organization of Microsoft, by sublimating them. Its ultimate outcome is a collection of hyper-growing spin-offs fueled by activities that have already reached their maturity stage, serving as a crucible for future innovations. More and more concrete examples are now operational: financial groups succeed in carve-out and IPO of hyper-growing activities supported both by exceptional market dynamics and by the promotion of a internal breakthrough innovation culture; pharmaceutical groups successfully arbitrate, on very specific perimeters, between in-house R&D and collaborations with biotechs on a human scale, or even buy them out if necessary; finally, digital service companies manage to isolate process outsourcing offerings allowing them to move up the value chain.

In a world where an unprecedented quantity of knowledge is accessible to a large number of actors, the intensity of disruptive innovation is increasingly strong. An indication of this trend is given by the combined inflation of the amount of data held by organizations, all statuses combined, and the number of proven unicorns on the planet (see already mentioned figure A above). Recall that a unicorn is, in the most common sense, an independent, unlisted company with an estimated capitalization of over US$ 1 billion. Thus, while the amount of information available grows exponentially, the number of structures capable of exploiting it to successfully innovate grows concomitantly. The mechanisms at work are no longer solely a matter of intuition, hard work and chance, but are increasingly based on proven processes and methods, while protecting the necessary freedom to create for individuals as for teams. In a way, the macro-trend for innovation has reached the beginning of its level of maturity, sorting out the actors equipped to last and the others.

Sources for figure B:

• The 10 Best Performing Stocks of the Decade, The Motley Fool, 2020.

• The World’s Biggest Startups: Top Unicorns of 2021, Visualcapitalist.com, 2021

• Presentation and correlation by C. Auriach (scenent.com)

In this context, a multinational like an SME cannot hope to develop sustainably without creating or participating in breakthrough innovations. Hyper-growth experiments are possible and seem within reach. The large established companies are aware of this and naturally seek more and more to compare themselves to the unicorns, so as not to risk suffering from the market. As there are now more than a thousand of them, statistics exist and make it possible to carry out benchmarks on precise perimeters of activity, because these structures are most often very specialized. More generally, this is a characteristic of so-called hyper-growth companies, which in fact constitute benchmarks in terms of performance (see already mentioned figure B above).

As liquidity remains abundant, one of the major challenges for managers is to steer them towards the right innovation projects, and therefore to identify the dynamics with the best potential. The question then arises of the target economic model, somewhere between the two extremes of the investment fund and the synergistic group exercising a broad spectrum of professions. In the pharmaceutical sector, for example, historical laboratories have to make choices between internal R&D and the acquisition of biotechs at the right stage of development, between producing and having them produced, between optimizing and innovating, both at the strategic level and at the operational level. Finding the right compromise between specialization and a multifunctional approach on the one hand, and on the other hand between a continuous innovation approach and a disruptive dynamic aligned with fundamental trends, constitutes a major challenge. It starts with setting goals aligned with the trends the organization believes in.

The major development goals of an organization must be clear, conscious and stable enough in a changing world to be effectively shared with its ecosystem (in and out). They depend on a good appreciation of market conditions and the reality of existing offerings and capacities, in order to determine a readable and lucid roadmap. As part of this training, an analysis framework that can be operated by executives of all levels, alone or in groups, is proposed to carry out this work. Three main families of sustainable development objectives should be considered and broken down according to the culture, potential and aspirations of the organization’s stakeholders: creating or embracing trends, existing in one or more niches, being or becoming a reference local actor, or a combination of the three. Distinct but coherent objectives can be declined by subset of the organization.

To achieve these sustainable development objectives, an appropriate innovation strategy must be adopted, for example changing economic models, focusing, choosing niche markets with little or no competition, continuous improvement, arbitration of target markets, automation and robotization, or partnerships and mergers. This list is not exhaustive. At this stage, it is already possible to evaluate certain projects in the light of the axes defined. Indeed, as soon as there is an innovation project underway in an organization, it is necessary to frequently ask the question of continuing, stopping, or changing the working hypotheses of the said project. From two projects, it is necessary to compare the potential of each frequently and possibly to arbitrate between them. These initiatives must at all times respect a logic of co-creation and constructive collaboration, by stimulating everyone’s creativity. A decision, one way or the other, is only taken after consultation and debate with the right people. As in a startup or a scaleup, pivoting is a potentially frequent occurrence. The statistics are cruel: out of 7 ideas, one will be successful. One of the major factors for improving this ratio is the consistency of the portfolio of innovation projects, its alignment with common objectives to maximize synergies, the dynamics of creative sharing and collective intelligence. While knowledge of the cumulative investment in innovation is necessary to be able to steer it, the return on investment is only calculable for a small subset of projects that have reached an advanced level of maturity. Uncertainty is a characteristic of the upstream phases of innovation projects and must be assumed otherwise creativity will be curbed, an untenable situation in the context described at the beginning of this text.

The dynamic of innovation is itself a space conducive to innovation. The planning, development, implementation and maintenance of an innovation project portfolio management process are all opportunities to create operational, organizational, strategic, cultural or relational disruptions within the organization. As part of this training, we propose a four-year approach with one one-day session per month, ie 48 sessions in all. By the end of the first year, elements of the process are in place on an experimental scale. If the organization is sufficiently mature, it can decide to anticipate their deployment in advance. Nevertheless, experience shows that many established multinationals have before them a major cultural, organizational and skills challenge requiring a profound transformation of practices, and therefore time is needed to convince, train, develop, communicate, demonstrate success by example, finally acquire lasting reflexes. Paradoxically, you have to be patient in order to one day be able to accelerate sustainably. Innovation is a muscle that we propose to train to take it to the highest level.

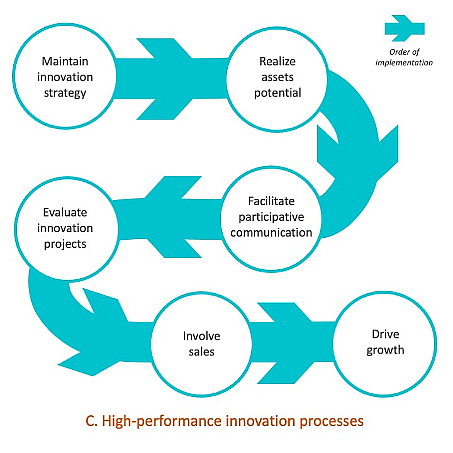

We choose to break down a state-of-the-art Innovation Portfolio Management process (IPM), benefiting both from the fruits of specialized management research and the experience of structures of various sizes and cultures, in 6 major capacities: maintenance of the innovation strategy, realization of the innovative potential of assets, participatory communication of innovation, evaluation of innovation, sale of innovation and the driver of innovation development (see figure C below). These 6 components benefit from being implemented in this order, starting with producing an updated innovation strategy and ending with the implementation of a growth engine creating value through innovation. Once in place, they are regularly improved by their process owners, either continuously or by introducing breaks.

Sources for figure C: C. Auriach (scenent.com)

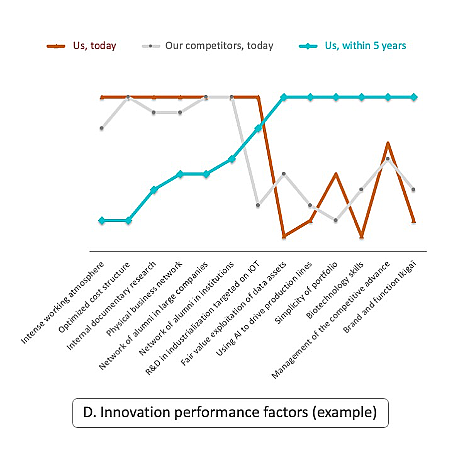

We propose a framework for determining an innovation strategy taking into account development objectives and the reality on the ground. The result is a set of strategic axes corresponding to the situation of each subset of the organization considered. Assistance in defining the scope of application of the IPM process is provided, based on a maturity model developed after a cumulative ten years of concrete experience, for example in the chemical and pharmaceutical industry sectors as well as in financial services. The gain provided by the updating of an innovation strategy is immediate: it allows making justified choices of investment and management of the organization, thanks to a dynamic of scripting. The scenarios are revisited each time the previous working hypotheses are brought to evolve under the pressure of the ecosystem or unforeseen events, undergone or provoked (Cf figure D below).

Sources for figure D: C. Auriach (scenent.com)

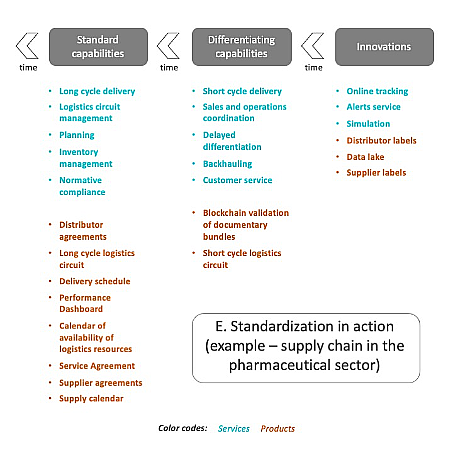

The realization of the innovative potential of assets makes it possible to detect and implement value-creating innovation opportunities (also called sources of value), such as internal software with a buoyant external scope of application, distinctive skills not yet transformed into offerings, prototypes frozen for lack of favorable budgetary arbitration, or descriptive data of a strong need not yet covered. This original and proven approach makes it possible to not depend solely on circumstances and fortuitous alignments of interests between stakeholders in order to innovate. The exercise which consists in identifying assets, tangible or immaterial, and confronting them with the strategic axes previously defined makes it possible to complete the portfolio of existing innovation projects with a new list with a strong potential. For example, an open innovation manager for a leading multinational in the construction and public works sector willingly confides that breakthrough innovations within her group are systematically at the crossroads of two dynamics: on the one hand the identification of a strong and unmet need, on the other hand the identification of dormant assets. We propose a simple and effective asset identification model that can be widely shared at all levels in dedicated workshops (see figure E below).

Sources for figure E: C. Auriach (scenent.com)

Participatory innovation communication makes it possible to involve the organization’s employees in the construction and dissemination of the targeted culture of innovation, thus accelerating the achievement of group efficiency objectives (collective agility), contributing to retain or attract critical talent, encouraging creativity while avoiding the dispersion of creative energy. A method of facilitating co-creativity workshops is proposed in order to materialize the production of content of all kinds, textual, visual or sound, intended to be shared on various channels inside and outside the organization. The first year, the collaboration tools already present in the company are generally favored so as not to add-up too many simultaneous changes. From the second year, specialized IPM software solutions are gradually introduced to manage both the internal project cycle and an open innovation approach, potentially including partners, customers and prospects.

The evaluation of the innovation makes it possible to compare oneself with the competition, internally and externally. The portfolio of innovation projects is evaluated using a series of methods adapted to each situation, emphasizing both the efficiency and the homogeneity of the approach in order to make relevant, rapid and useful comparisons. At each iteration, trade-offs are potentially made, a portfolio of innovations being by definition eminently dynamic. 4 types of management plans are proposed, from maintaining a competitive lead to penetrating a market niche, through value-added partnerships and operational excellence initiatives.

The sale of innovation makes it possible to plan as far upstream as possible the mechanism for marketing an innovation, considering it as an integral part of the offering, product or service, in the same way as a material or a manufacturing process treatment. Salespeople become sensors of trends and needs and are an integral part of the teams involved in innovation from the beginning to the end of projects. In terms of information systems, extended CRMs are now as strategic as ERPs and the issues of interfacing between the two capabilities are at the heart of increasingly heavy investments. Beyond the involvement of men and women in direct contact with prospects and customers, the choice of channels for presenting offerings is crucial: multichannel approach, chatbot-assisted sales, customized demonstrators, coupling product and services, as many examples of possible choices (non-exhaustive list). In reality, the sales channel is part of the offering. The more the possibilities offered by artificial intelligence develop, the more significant this principle becomes.

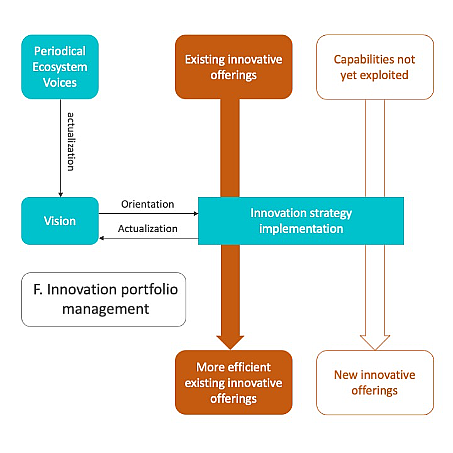

Finally, the innovation development engine is an agile system focused on increasing the value of innovation. It is made up of dedicated professionals within innovation cells with variable geometry, created according to needs and disappearing when the need fades or the working hypotheses evolve, in favor of new cells assigned to new needs deemed to be priorities. One of the methods put forward consists in creating communities of interest around innovative products and services even before they are put on the market, in order to carry out potential impact assessments that feed arbitration decisions and investment. The members of the cells maintain and present dashboards for monitoring and arbitration of the dynamics of innovation within the organization. The nature of the indicators is aligned with the sustainable development objectives and with the innovation strategy (see figure F below).

Sources for figure F: C. Auriach (scenent.com)

Future outlook

Ensuring that a strategic choice is sustainable is a permanent challenge. In terms of innovation, one of the ways to improve its success rate is to imagine the future in the form of scenarios (see already mentioned figure D above). The content of the scenarios varies according to a variable deemed relevant given the context of the organization concerned: ambition, scope of deployment, evolution of the ecosystem, structuring trends, evolution of the expectations of the targeted markets, potential of the assets are just a few examples of such variables. If the future is never certain, it is still possible to say that if such a set of hypotheses is verified, then such and such a scenario is appropriate. When the hypotheses vary, it is of course necessary to update the scenarios in order to make the organization manageable. For example, ABC already mobilizes significant resources in order to identify positional rents on the market, which it chooses to compete on the basis of a scientifically assessed penetration potential. The insurance sector thus becomes a privileged target, first by offering comparators, then by offering products.

Scenario planning, underpinned by the exploitation of mass data, by machine learning and deep learning, by the rapid interpretation of information captured by connected objects and by human intelligence (interacting in an efficient and serene way with these devices) is the future of successful innovation processes. This dynamic will gradually replace more traditional methods, for example the PESTEL analysis, which have become unsuitable in a time of accumulation of successive crises linked, among other factors, to a generalized interconnection between geographies, economies, individuals and natural phenomena, which make any event propagable at high speed on a planetary scale. The exercise of simulation now struggles to be carried out by human intelligence alone. It needs, like a chess player assisted by a computer analysis program, to be reinforced by the use of automated processes endowed with an unprecedented level of autonomy, while retaining control.

Future innovation management models could be described as crisis managers, capable of transforming probable threats into short-term opportunities. The resulting organizational systems would then resemble collections of specialized cells over a short time horizon, the cells forming and disintegrating according to the anticipation of crises. This logic would be in a way an extension of the Sprint, agile and other Scrum approaches that are flourishing today, revisited to stick to scenarios duly supported by data. To illustrate this trend in the pharmaceutical sector, forecasting the amplitude of the development of crises as soon as they emerge is a determining success factor for innovation choices, as evidenced by the gigantic gap separating the winners from the losers in a period of global pandemia. Another example, the situation of large companies in the energy sector will constantly oscillate between scarcity and abundance depending on events of a geopolitical nature, combined with increasingly frequent and disruptive innovations, creating dazzling growth accelerations and decelerations in a variety of markets with distinct behaviors.

The main obstacle to adapting to this new situation will be the ability of individuals to question themselves. The shortage of key skills is already visible in this field and will only increase in the medium term. It is therefore urgent to create the conditions for the evolution of today’s professions towards the professions of tomorrow, both in terms of interpersonal skills and know-how, even if it means getting used to interacting more and more with avatars, but not only.

Curriculum

High-Performance Innovation – Part 1 – Year 1

- Part 1 Month 1 Scope Definition

- Part 1 Month 2 Strategic Positioning

- Part 1 Month 3 Setting Objectives

- Part 1 Month 4 Innovation Culture

- Part 1 Month 5 Organizing Innovation

- Part 1 Month 6 Asset Potential

- Part 1 Month 7 Methodology Sharing

- Part 1 Month 8 Pilot Projects

- Part 1 Month 9 Reporting Results

- Part 1 Month 10 Prioritize Actions

- Part 1 Month 11 Program Schedule

- Part 1 Month 12 Communicate Plan

High-Performance Innovation – Part 2 – Year 2

- Part 2 Month 1 Innovation Patterns

- Part 2 Month 2 Innovation Cycle

- Part 2 Month 3 BBZ Approach

- Part 2 Month 4 Selecting Software

- Part 2 Month 5 Valuing Innovation

- Part 2 Month 6 Benchmarking Innovation

- Part 2 Month 7 Facilitating Innovation

- Part 2 Month 8 Promising Trends

- Part 2 Month 9 Portfolio Management

- Part 2 Month 10 Sustainable Innovation

- Part 2 Month 11 Servitization Model

- Part 2 Month 12 Innovation Management

High-Performance Innovation – Part 3 – Year 3

- Part 3 Month 1 Customer Voice

- Part 3 Month 2 Innovation Structure

- Part 3 Month 3 Training Program

- Part 3 Month 4 High-potential Assets

- Part 3 Month 5 Innovation Dashboard

- Part 3 Month 6 Spinning-Off

- Part 3 Month 7 IPM Software

- Part 3 Month 8 Open Innovation

- Part 3 Month 9 Self-Assessment

- Part 3 Month 10 Communicate Strategy

- Part 3 Month 11 Involve Sales

- Part 3 Month 12 Generalize IPM

High-Performance Innovation – Part 4 – Year 4

- Part 4 Month 1 Performance Analysis

- Part 4 Month 2 Update Dashboards

- Part 4 Month 3 Visual Management

- Part 4 Month 4 HR Lever

- Part 4 Month 5 Technology Lever

- Part 4 Month 6 Prototyping Lever

- Part 4 Month 7 Modeling Lever

- Part 4 Month 8 Agility Lever

- Part 4 Month 9 AI Lever

- Part 4 Month 10 Symbolic Lever

- Part 4 Month 11 M&A Raising

- Part 4 Month 12 Next Steps

Program Objectives

The following list represents the Key Program Objectives (KPO) for the Appleton Greene High-Performance Innovation corporate training program.

High-Performance Innovation – Part 1 – Year 1

- Part 1 Month 1 Scope Definition – The approach is adaptable to the size of the structure. Thus, we distinguish 3 levels from the SME (or scaleup) to the multinational, passing by the unicorn-like organization. In the case of a very large organization, deployed in several dozen countries, it is necessary to break down the scope of application of the approach into manageable units. For each of them, an IPM strategy is defined. After having introduced the origin, the interest and the success factors of an IPM process, a method is proposed to carry out this division. It is based on the assessment of the level of maturity of the innovation process and its variations depending on the regions, legal entities or businesses. The idea is to group together the homogeneous subsets of the organization from the point of view of the maturity of the innovation process. To achieve this, a 12-level model is proposed. These 12 levels are themselves grouped into 4 zones (detection, measurement, opening and prioritization). These zones correspond to levels of maturity of the process. The actors of this first evaluation are leaders, managers, project managers or directors of innovation projects. The approach is all the more visible and effective as the decision-making power of the first actors mobilized is great. For example, the members of the executive committee can divide up subsets of the organization and mobilize to gather information allowing them to refine or confirm the assessments of the level of maturity of the process, before meeting to share a vision and an IPM strategy. The results of this step are recorded in an existing collaborative tool, pending the subsequent selection of a more specific technical environment. Each step of defining the scope is illustrated with a realistic example, freely inspired by several real cases in the pharmaceutical industry sector, and nevertheless fictional.

- Part 1 Month 2 Strategic Positioning – At this stage, the first strategic level objectives are identified. They will be constantly refined as the IPM process is planned, developed, implemented and improved. In particular, the stimulation of a dynamic of connection to representatives of the target markets of the organization is proposed. This involves organizing pilot project meetings with witnesses of these markets, prospects, customers and partners of the organization, in order to better understand their aspirations in terms of customer or partner experience. Employees who have already participated in the previous information collection phase, in contact with the leader(s) of the initiative, are naturally approached to lead these sessions for half a day each. They must be trained in the proposed animation method, which is precise and proven in around fifteen different professions. Strategic positioning leads to a collection of current and future performance factors relevant to the scope of the pilot projects considered. They make it possible to complete IPM’s strategy with strategic axes of innovation such as changing an economic model, focusing on continuous improvement through lean, rapprochement or partnership with more agile than oneself, or focusing on a decisive competitive advantage. The same case of a pharmaceutical laboratory is used to illustrate this phase of the approach. In order to start sharing a common repository between the protagonists of the IPM project, a flexible and simple collaborative environment chosen during the first stage, preferably already existing within the organization, is configured for this purpose. It will allow the various stakeholders to classify the results and access them according on a need to know basis. In particular, the contributors to the identified pilot projects will be among the authorized persons.

- Part 1 Month 3 Setting Objectives – The first elements of the innovation strategy, existing and new, are translated into concrete projects, with project file, prospective team, expected return on investment and budgeting. It is critical to ensure that creativity and entrepreneurship are not undermined by over-bureaucracy. Also the project mode is resolutely favored, taking up the pre-existing codes within the organization and carefully balancing freedom to create and control of investment. It is only gradually that the culture of innovation spreading, new reflexes inspired by agile methods will complement the old ones. A framework for arbitration between two projects with an equivalent level of investment and ROI will be proposed. It takes up the dimensions of the innovation strategy already established and makes it possible to verify the alignment of an innovation project with these strategic orientations. It is illustrated by an example deduced from the “common thread” case study. In steady state, the role of the IPM is to constantly improve the performance of existing innovative offers, and to create new ones by exploiting assets with potential. A first monitoring dashboard is proposed and illustrated by the “common thread” case study. It identifies the relevant indicators given the context, their target valuations, their units, their completion time and the means of measurement used. At this stage, the approach is of the continuous improvement type, inspired by Lean and adapted to the management of a portfolio of innovation projects. It allows the concept to be tested on a limited perimeter before future deployment and scaling up. The tool supporting this dashboard is common to other reporting sectors, reusing known practices in order to save time while simplifying the number and complexity of validation stages, where applicable.

- Part 1 Month 4 Innovation Culture – There are several types of innovation cultures, illustrated by emblematic examples, from the World Bank generalizing a clever process imagined by an African nurse, to the innovation ecosystem structured by Apple, passing through the selection funnel of ideas of a Pixar or a Disney. They are often the result of successive developments experienced either by the organization itself, or by their founders or managers in their professional lives. The objective here is to build a message and a cultural repository consolidating the identity of the organization in its innovative dimension. In practice, it is just as critical to consider the future as the past, by calling upon sets of hypotheses and scenario building, to identify the fundamentals of a culture of value-creating innovation. The lessons of the past are mainly drawn from the study of successes and failures in innovation. Retrograde analysis of the causes of these successes and failures, by interviewing the project managers involved if they are still employed by the organization, or by collecting information from the departments responsible for capitalizing on the knowledge if they exist and have this type of analysis, makes it possible to identify typical patterns corresponding to the potential pillars of this culture. With regard to the future, a set of promising trends has been identified by a working group linked to the strategic function of the organization. A method is proposed for, on the one hand, choosing the tendencies in which the organization believes, and on the other hand, for developing hypotheses relating to the occurrence of events suffered or provoked. This results in scenarios that are more or less probable and more or less value-creating. A narratology exercise concludes this phase, in order to convey in a pleasant form, easy to integrate into a communication plan, a message and a cultural repository consolidating the identity of the organization in its innovative dimension.

- Part 1 Month 5 Organizing Innovation – A number of collaborators were involved in the first four stages of IPM planning. It is proposed to them to be part of the first innovation cells, prefiguring the elementary entity of the future organization of the IPM. This is more of a loose membership in a club than a formal assignment to a structure at this stage. Nevertheless, it makes it possible to test with motivated personnel who have first experience of the voices of the customer (exercises to survey market expectations in terms of innovation) the target innovation culture, the level of spontaneous adherence to the orientations defined by the innovation strategy and their application to concrete projects. The members of the innovation cells are necessarily involved in innovative projects, in the sense that this word is defined in the innovation strategy of the organization in question. They give a duly documented opinion on the life of these projects and help align field experience and strategic objectives to make them credible and give them a concrete foundation during subsequent large-scale deployment. In particular, they create current stories of successes but also of failures, which complete the corpus gathered during the previous stage and feed the legend of the organization. Without prejudging the future structure of innovation cells, typical roles are identified. Relevant collaborators can jump from one role to another depending on the circumstances or topics, but for a given project, an individual is given only one role. An organizational model is proposed, including the roles of project leader, concept guarantor, prototype manager, functional expert, technical expert, scaler and communicator. We observe that there is no role dedicated to the generation of ideas, because everyone is concerned.

- Part 1 Month 6 Asset Potential – Among the mechanisms (or schemes) of innovation, the identification of assets with potential is particularly attractive, although rarely mastered by companies. Everything starts from the observation that each successful innovation is either the exploitation of a general opportunity, or the exploitation of a specific opportunity. A general opportunity could be exploited by other organizations with the same chances of success. A specific opportunity benefits from being exploited by an organization particularly capable of leading it to success, within more competitive deadlines and with a level of investment in time and human energy that is more controlled than in another organization. Exploiting a general opportunity implies detecting it before the others and moving very quickly to avoid being caught up, most often thanks to very heavy levels of investment. Let us think, for example, of the successive generations of mobile telecommunications standards, which are the subject of large-scale auctions. Innovation projects that build on such opportunities are by definition few in number and managed at a highly strategic level. If they are good candidates to be part of an innovation portfolio, they appear there as large carriers escaping the overall statistics of the said portfolio. Exploiting a specific (to the organization) opportunity is of great interest since there is a latent competitive advantage just waiting to be transformed into value. To achieve this, opportunities of this type need to be identified and an appropriate investment policy adopted, based on a detection, prioritization and implementation method. A solution involves a model of assets with potential to collectively scan the field of possibilities and to deduce a selection of most often new projects, based for example on a distinctive skill, a forgotten prototype or transposable software in a new application context. To avoid casting too wide a net and thus risk losing control of the process, it is confined at this stage to looking for projects with very high potential. To fix the ideas, it is a question of detecting opportunities capable of becoming hyper-growing spin-offs within a two-year horizon.

- Part 1 Month 7 Methodology Sharing – The project portfolio at this stage contains lines resulting from the voice of the customer, the historical dynamic of innovation, the reactivation of old projects in favor of new market conditions and large carriers linked to general opportunities or specific asset exploitation opportunities. The innovation portfolio is gradually expanding with new projects suggested by members of the innovation units and prioritized by decision-makers who are increasingly involved in the IPM approach. In order to control the growth in number and quality of projects registered in the portfolio, a project audit methodology is proposed. It is first used as an entry filter for a new line in the portfolio, before being applied, later in the IPM deployment cycle, to existing lines. It takes up the achievements of the previous stages, for example the framework for arbitration between two projects of equivalent level of investment and ROI, by supplementing them with tools and methods for defining and validating operational models and economic models. The members of innovation cells and their privileged correspondents must be trained in the operational and economic modeling of projects using simple and effective frameworks that have proven themselves in several very different sectors from each other. Participants in this training receive guidance in facilitating these trainings. As leaders of the innovation process in their organization, they are called upon to disseminate good practices and to be trainers themselves, through theory, practice and example. An illustration in the context of the common thread pharmaceutical laboratory is offered to them, thanks to the analysis of two typical projects, one multi-year, the other supposed to generate value in the shorter term. It is also proposed to build a business case close to the reality on the ground of their organization, serving as a guiding thread for the training they are required to provide.

- Part 1 Month 8 Pilot Projects – It is important to capitalize on the achievements of each stage in the collaborative environment chosen for this purpose. Methods, tools, portfolio, decision records, callouts, strategic directions, trends, voice of the customer results, innovation process maturity, success factors, goals, dashboards, role definitions, asset lists and training courses kits are duly listed there and made accessible according to the need to know. With these resources, the organization is ready to anticipate results over a period ranging from a few weeks to two years. Why two years? Because it is a limit beyond which the visibility of a market context becomes too difficult to assess with sufficient reliability. Admittedly, the return on investment horizons of funds specializing in innovation are more like seven years on average; but they require tangible results before this deadline: we speak of visible steps. The challenge is to announce more and more good news as the IPM project unfolds. This is made possible by the gradual improvement in the success rate of innovation projects, by the reinvestment of earnings, by extending adherence to the approach to new subsets of the organization, by connecting approach to the expectations expressed by the voices of the customer and by the dissemination of a culture of innovation that is as attractive as it is effective. It is on this condition that the momentum of the IPM initiative is sustained over time. A number of pilot projects are identified as having the potential to become cardinal models of success for the future. They are chosen according to their operational terrain, their nature, their time horizon and their high chances of success. All of these pilot projects cover a spectrum of functions, technologies, skills and market segments representative of the variety of situations in which the organization wishes to innovate. The statistics are terrible: between 80% and 90% of new products and services do not last beyond the first year of operation according to specialized academic sources; and this is true everywhere in the world. The only factor that increases the probability of success is the quality of innovation management. These pilot projects make maximum use of the content of the repository shared via the collaborative environment and constitute a privileged illustration of it, becoming in fact the examples cited in future training and communications.

- Part 1 Month 9 Reporting Results – There comes a time when higher-level decision-makers demand accountability. This is an opportunity to involve them in the process and to transform them, if they have not already done so, into its powerful promoters. To do this, at least three challenges must be met: ensuring that they recognize their own agendas in that of the IPM, that they are pleasantly surprised, either by the first results already recorded, or by favorable echoes contributing to maintaining the confidence, finally that they learn something. “Tell me about something that I don’t know yet”, said the President of a large bank who had just given an hour to a project team in charge of applying a lean method to a management control process deployed on a multi-country and multi-business scope. These three principles should guide the development of high-level reporting. We must compare innovation to an art, and realize that in musical composition for example, if inspiration plays a big role, in fine the dissemination of a work on a large scale passes through the use of a universal notation, and the exploitation of techniques and practices that it usually takes ten thousand hours to learn in a conservatory. So it is an art, yes, but it is also a body of knowledge and know-how whose impact must be demonstrated in these high-level reporting bodies. Success ratios, levels of mobilization, performance gaps between a standard innovation project and a pilot project, future spin-offs, so many key topics that must be presented in the right order and with a convincing argument, starting with the conclusion and unfolding its rationale rather than the other way around. Indeed, the common reflex is to report on the approach in the order in which it unfolds, starting with the first step and ending with the last, where the results finally appear. This is to be avoided, in favor of a more assertive, more surprising, more audacious communication. A reporting process is also in itself an opportunity to innovate. You have to know how to take advantage of it.

- Part 1 Month 10 Prioritize Actions – With the sum of innovation projects in the portfolio increasing month after month, it becomes possible to begin to establish relevant statistics and observe repeatable patterns. In particular, the decision-making process must be the subject of particular attention insofar as it is often a bottleneck and a factor slowing down the deployment of IPM. Very often, optimizing this process is unavoidable. High-level involvement is of course a non-negligible success factor for this initiative. The list of assets with potential is expanding and is being aligned with the innovation strategy. Any opportunities to protect intellectual property or file a patent are studied, and the corresponding policy is updated if necessary. Some organizations set targets for the rate of registration of patents or even publications in scientific journals. Large high-tech companies go so far as to invest in fundamental research, considered as a basis for applied research; this approach also makes it possible to recruit exceptional talent in a context of shortage of specialized skills. Patents or assets with potential that do not fit into the innovation strategy, or that are regularly arbitrated in favor of other assets, may be sold to third-party organizations, which represents another lever for creating value. The decision-making process integrates the handling of this type of file, usually involving a high level while respecting the necessary imperative of efficiency. The pilot projects federated in the innovation portfolio integrate the objectives of protection and exploitation of intellectual property. Major multi-year projects are the subject of particular attention, insofar as their success generally depends on long and costly research and development efforts. Principles of management, arbitration and pivoting specific to these projects are shared.

- Part 1 Month 11 Program Schedule – A progress report is carried out in order to put the major milestones of the deployment program into perspective. In particular, the dependencies between the achievements and the objectives remaining to be achieved are identified and illustrated on a PERT-type diagram, before being transposed into a GANTT. Iterations take place between different stakeholders to consolidate the plan before wider dissemination and sharing. The deadlines envisaged for the carve-out and launch of high-potential stand-alone entities, considered as possible future hyper-growth structures (for example, spin-offs deemed capable of becoming unicorns), constitute strategic milestones. Their positioning in a multi-year schedule must take into account the time needed to separate them from activities or offerings that do not have the same potential, to mobilize key resources, to overcome the obstacles identified in terms of economic models, technological challenges, skills, communication and possibly resistance to change. It is important to position them in time from the first year, when the IPM process is not yet deployed on a large scale, in order to be in a position when the time comes to exploit these very visible and even spectacular stages with a view to stimulate membership. Some of these conclusions are widely communicated, depending on the need to know : key milestones, strong needs not yet covered (identified as privileged breakthrough fields of innovation), stabilized method elements, results obtained at this stage, statistics relating to the portfolio of innovation projects. The objective is to share an expectation expressed by both internal and external actors in the organization, before structuring the customization phase of the IPM process (second year).

- Part 1 Month 12 Communicate Plan – The action plan is the subject of targeted communication inside and potentially outside the organization. Success stories already recorded, as well as mastered, explained and analyzed failures, contribute to creating a specific and shared culture of innovation. This communication plan sets the stage for the next phase, dedicated to customizing the IPM process. The components of the process and the issues specific to each of them are recalled. At the level of the maintain innovation strategy component, the objectives include the launch of an open innovation approach, a specific budget approach to innovation, an adapted IT equipment plan, preparation for the launch of potentially hyper-growing activities, an evolution of the career model and target skills, the selection of key trends, and the alignment of innovation KPIs with CSR objectives. At the level of the realize assets potential component, the objectives include the recognition of recurring innovation patterns and mechanisms, the initialization of an open innovation portfolio, the testing of an end-to-end IPM process, the customization of IPM software and the initialization of an agile portfolio. At the level of the facilitated participatory communication component, the accent is placed on training initiatives for personnel called upon to contribute to innovation projects, on calls for participation in open innovation initiatives (inside and outside the outside the organization), and on the key points of IPM’s innovation strategy and strategy. At the level of the evaluate innovation projects component, the objectives include the definition of the innovation cycle, the implementation of a benchmarking and project evaluation approach, the definition or update of a reference management system for agile projects, an IPM service level agreement and the implementation of effective IPM reporting. At the level of the involve sales component, the objectives include the mobilization of communities of witnesses of the ecosystem, the contribution to open innovation and the identification of priority trends and the adoption of a dedicated sales action plan. At the level of the drive growth component, the objective is to create and maintain the repository of IPM processes applicable on a large scale from the third year.

High-Performance Innovation – Part 2 – Year 2

- Part 2 Month 1 Innovation Patterns – Innovation can be achieved in various ways, formal or informal. In all cases, patterns of innovation were identified through post-analysis of successful innovations and experience of their implementation. Transposition, coopetition, model mutation, so many areas of reflection allowing both to guide the teams concerned and to reuse proven good practices. The idea here is to select the innovation schemes best suited to the context of the organization in question. Identifying and promoting innovation patterns is part of the realize assets potential component. Its objectives are to make the organization aware of the detection of innovation opportunities, to feed subsequent training programs, to help create a common culture, to facilitate the establishment of statistics and the identification of success factors. For example, transposition is a pattern common to many innovative organizations. It consists of adapting a process deemed virtuous in one area to another area. This domain can be a market, a manufacturing step, or any definition of the scope of application of said innovation mechanism. Typically, noting that the success of the introduction of the Iphone on the market is due, among other factors, to the simple idea of combining three devices into one to concentrate frequent uses on it, an industrialist in the pharmaceutical sector may decide to combine three active ingredients in a single drug to concentrate the treatment of particularly widespread pathologies. If this works, the transposition of the process can then be envisaged for three devices for measuring health constants combined in a connected watch, then for three sensors for tracking a package at the supply chain level.

- Part 2 Month 2 Innovation Cycle – The innovation cycle generally includes the phases of ideation, design and prototyping, exposure and deployment. But each organization is free to chart its course in its own way. Beyond the known cycles resulting from experience, nothing prevents us from innovating at the very level of the innovation process. This personalized cycle will then be used to perform consistent reporting across the organization. The definition of the innovation cycle is part of the evaluate innovation projects component. Its objectives are to harmonize the way in which projects are planned, estimated and monitored, to facilitate decision-making, to feed subsequent training programs and to allow various profiles to work together quickly, after a shortened synchronization phase. On this occasion, the profiles of asset pilots, project facilitators and ecosystem animators are identified. Asset pilots are mainly in charge of the realize assets potential component of the IPM process, project facilitators are mainly in charge of the evaluate innovation projects component, while ecosystem animators are mainly in charge of the involve sales component. These professionals are trained to train other employees involved in innovation projects in the elements of the process stabilized at this stage. For example, if a prototyping approach is favored each time the investment exceeds a certain threshold, or if there is a panel of market witnesses available to test it in an upstream phase, this rule will be part of the definition of the innovation cycle. Resources and prototyping tools can be recommended and customized according to the culture, constraints and objectives of the organization in question.

- Part 2 Month 3 BBZ Approach – The budget process applied to innovation is preferably of the ZBB (Zero Base Budget) type. This means that the budgets are validated over time, depending on the detection of assets with potential and the emergence of promising projects. The deviations and accelerations of projects observed are consolidated in order to carry out arbitrations within the portfolio. This process must be compatible with the standards of the organization and fit into them as harmoniously as possible. The BBZ approach is part of the maintain innovation strategy component. It is defined by a level of management high enough to have a cross-functional impact. Its objectives are to avoid the recurrent renewal of annual budgets devoted to innovation (with systematic reassessment and updating), to connect the budget envelopes to the reality on the ground and to needs aligned with the innovation strategy and IPM’s strategy, and to respect the principle of frequent arbitration between projects (with the aim of identifying pivoting opportunities at the right time). For example, if a research and development department specializing in the industrialization process of the company’s products increases its budgets by 7% each year, with no other justification than an alignment with the group’s sales growth rate, looking at the portfolio of innovation projects and asking the question of its performance proves useful. Are disruptive innovations planned or already implemented? Do they need to be encouraged by a budget extension, or on the contrary arbitrated for lack of results after several years of trial and error? What patterns of innovation are at work? What synergies can be expected vis-à-vis the rest of the portfolio and the methods and tools proven at this stage? What indirect benefits can we hope for that were not foreseen at the start of a project? Resetting the counters to zero and revisiting the triggers of the projects makes it possible to give them an impetus aligned with the strategy or to make an arbitration decision specific to freeing up and redirecting the mobilized capacities.

- Part 2 Month 4 Selecting Software – There are many software packages dedicated to IPM. Beyond the first collaborative environments mobilized at the start of the program (planning phase), generally based on what already exists, it is necessary to professionalize the computerization of the process over time. For this, a master plan is proposed in order to find its place in the information system of the organization, while respecting its standards and constraints or by making them evolve in a justified way. Building the master plan is part of the maintain innovation strategy component. It involves the information systems department and is part of its roadmap. Its objectives are to facilitate an open innovation approach, to efficiently generate statistics and decision support, to share methods and tools, to structure and provide online training, to supervise innovation cycles and to facilitate the participatory communication. If a solution already present in the group’s information system is selected, its configuration must take into account the choices made at this stage. For example, if an initiative to call on external skills is launched to solve a complex customer experience problem, the greater the range of actors solicited, the greater the chances of success. Specialized software gives access to hundreds of thousands of startups, researchers, experts and design offices potentially able to offer their services and save the organization time. In this case, such a problem may have already been encountered on the other side of the planet and the solutions put in place may be rapidly adapted to this new context.

- Part 2 Month 5 Valuing Innovation – The projects in the portfolio are subject to a value analysis initiative. Any innovation project can be linked to one or more initial assets, the value of which has changed at the end of the cycle. The method for evaluating the impact of an innovation project is determined on the basis of a generic proposal. The valuation of innovation projects or underlying assets is part of the evaluate innovation projects component. Its objectives are to manage the consolidated value of the portfolio over time, identify carve-out and spin-off opportunities, identify hyper-growth potential, and compare it with internal performance benchmarks as well as external ones. This original approach has proven itself efficient in various contexts, making it possible to overcome the limits of reporting focused mainly on the notions of investment and return on investment. Indeed, reasoning by value potentially affects the balance sheet and not only the income statement, thus widening the horizon of potential innovations. For example, if an innovative centrifuge prototype that had been sleeping in a laboratory cupboard for several years gets a second life thanks to an ongoing project, there is a sudden appearance of value. It is essential to capture this phenomenon, to manage it and possibly reproduce it elsewhere. It is also possible that the expected value at the start of the project decreases or increases after reassessment, which leads to readjusting the objectives, or even pivoting, considering a spin-off or deciding to suspend the investment in favor of a more advanced – or more promising – project.

- Part 2 Month 6 Benchmarking Innovation – In order to compare themselves to the leaders, specialty by specialty, a method is proposed. It is based on “voice of the customer” type exercises that are now well known to the organization since they condition the alignment of projects with market expectations. It is customized to fit into the organization’s target innovation culture. The benchmarking process is part of the evaluate innovation projects component. Its objectives are to give benchmarks to the actors of innovation, to generate a healthy emulation following the example of the palpable dynamics within startups and scaleups, to raise awareness of the importance of steering competitive advance, to gauge the effort required to catch up with or overtake a competitor, or to move away from overly competitive markets. For example, if in a supply chain ecosystem, there is a gap between the benchmark considered by professionals internally, and the benchmark considered by the group’s BtoB customers, the customer experience is potentially disappointing. In this type of analysis, the commercial function can be called upon to collect and organize information from the field. They animate communities of witnesses of the ecosystem participating in the definition of service levels dictated by the best practices observed. Focus group type workshops are organized at regular intervals, either virtually or physically, the sales representatives in charge of their animation having been previously trained and integrated into the innovation cells. Their conclusions are analyzed and shared on the collaborative environment dedicated to innovation, in order to serve as a decision-making aid in the project management bodies.

- Part 2 Month 7 Facilitating Innovation – The members of the innovation cells will themselves have to train their colleagues in basic workshop facilitation techniques, in accordance with the strategic axes adopted during the planning phase. Before sending them to the field for this purpose, they are trained to train. Their career model is defined and gradually rolled out at the HR level. The facilitating innovation activity is part of the facilitate participatory communication component, at the junction between the functions of human resources management and communication. Its objectives are to create a homogeneous and effective culture of innovation, to disseminate good practices quickly and fluidly, to recognize the contribution of the personnel dedicated to this initiative at its fair value and to propose new ways of developing careers. For example, the configuration and use of new software dedicated to innovation can generate resistance to change with various causes: perception of the arrival of an additional administrative layer, lack of knowledge of preferred use cases, lack of training, lack of time, poor prioritization of tasks, problems with the quality or performance of the solution. The training of trainers must enable them to anticipate these obstacles and to propose answers and good practices to the participants in the trainings that they will provide themselves. This means encouraging them to maintain ongoing relationships with various profiles within the organization, from the IT specialists in charge of the solution to the most experienced users, including the most visible refractories and the most strategic sponsors. Because a solution is not just software, but a combination of constantly evolving behaviors, processes, strategic objectives and tactics.

- Part 2 Month 8 Promising Trends – In order to avoid the Kodak syndrome (namely the involuntarily suicidal behavior of a company which holds a decisive asset in the laboratory but does not industrialize it for fear of self-competition), a bouquet of trends in which the organization believes is determined. This work makes it possible to contribute to arbitrating between projects judged to be equivalent from the point of view of their potential. Identifying and selecting trends in which the organization believes is part of the maintain innovation strategy component. These trends are considered both sustainable and promising, specifically for the organization and its ecosystem. The activity aims to provide benchmarks to all professionals deployed on innovative activities, the focus of documentary research and monitoring work on keywords and key expressions deemed strategic, the orientation of benchmarking work on a manageable scope and the natural emergence of new innovation opportunities. For example, if biosynthesis techniques are considered to have potential for a broad spectrum of applications, the presence of representatives of the organization is essential in this ecosystem. It can take the form of an open innovation partnership with a university, collaboration with a scaleup in the sector, participation in congresses and conventions dedicated to the subject or the financing of collaborative projects. The scientific and competitive watch function will also be mobilized to provide the teams of the projects concerned with up-to-date and operationally usable information. All staff will be made aware of this topic in order to contribute to the detection of new opportunities around them, in their context and their daily lives.

- Part 2 Month 9 Portfolio Management – The IPM process is ready to be deployed. End-to-end simulations are carried out on real cases in order to test the system transversely. The observations are categorized according to procedural, human, technological and strategic dimensions. The portfolio management activity is part of the realize assets potential component. Each innovation project is linked to a description of one or more underlying assets and its expected or measured valuation, to one or more promising trends, to one or more innovation mechanisms, to one or more performance factors, to one or more axes of the IPM strategy. Simulating end-to-end portfolio management functions allows collecting and implementing improvement suggestions before deploying them on a large scale, verifying their reliability and ease of use, helping to generate buy-in to the process, to prepare for the following phases and to emphasize the importance of sharing a well-understood culture of agility. For example, if methods already exist within the organization, materialized by buzzwords such as scrum, sprint, agile, design thinking or jugaad, should they be integrated into the IPM process, should they be considered as opportunities to create synergies, or should they simply used in a pragmatic and uncodified way? Most often, the solution lies in flexible referencing in the form of a capacity to contribute to innovation, with correspondents and experts potentially integrated into the innovation cells. If one of these methods proves to be essential and constitutes the common denominator of many successful innovations, it is gradually nourished by this feedback and benefits from the sharing of best practices in the field.

- Part 2 Month 10 Sustainable Innovation – At this stage, the process has a transverse existence. The portfolio already contains pilot projects, some of which are identified as having a marked societal or environmental impact. Since the beginning of the IPM project, sustainability reporting standards have been specified and constitute new reference systems that must be cross-referenced with that of the IPM. The sustainable innovation activity is part of the maintain innovation strategy component. Its objectives are the alignment of the innovation dynamic with the organization’s sustainable development strategy, the targeted facilitation of communities representing the ecosystem from the point of view of CSR (corporate social responsibility) issues, the creation of synergies between open innovation and regional economic development, raising awareness among salespeople of the results already obtained and providing details on trends deemed to be promising. For example, if the carbon footprint of a network of factories presents a significant level of heterogeneity, the causes of these differences are analyzed from the angle of the realization of the potential of dormant assets, or the transposition of processes that have worked in one place and can be adapted to another place. The search for breakthrough innovations is favored, in preference to a logic of continuous innovation, in order to generate the most significant gains possible, to create particularly visible performance leaps and to avoid any confusion with projects that do not present with a marked innovative aspect. An indicator of the success of this approach is the identification, launch and even completion of promising new projects thanks to IPM. The use of open innovation is particularly suited to the context, because an external dynamic can prove to be virtuously contagious and accelerate internal mobilization around these issues.

- Part 2 Month 11 Servitization Model – A map of the services provided by the IPM is produced and published. For each of these services, performance level commitments in accordance with the organization’s quality, time and profitability requirements are established. The establishment of a servitization model is part of the evaluate innovation projects component. Its objectives are to recognize the contribution of IPM at the level of the subsets of the organization on which it is or will be deployed, to measure its perceived and actual performance, to create the conditions for its effectiveness, the establishment of service contracts with its direct beneficiaries, the availability, updating and dissemination of a map of the services provided, and its integration into the list of potential assets of the organization for improvement purposes keep on going. IPM is a space for innovation in itself and should not be an exception to the rule. A servicization model can be considered as the transposition of capabilities that have proven themselves in the field of logistics in the field of IPM. Thus, Amazon Prime and AliBaba have deployed these models on a large scale with the efficiency that they are known for, with an unprecedented level of automation and a list of human issues that are also unprecedented. Servicization models consider everything to be a service, including products seen as collections of uses (and no longer as goods, machines, software, clothing or consumables). This results in a focus on service interfaces, their scope of application and their performance promises. If, for example, support is urgently requested by a salesperson to help him lead a voice-of-the-ecosystem workshop using the design thinking method, the timeframe for mobilizing the right experts could be agreed in advance and be subject to an appropriate service contract.

- Part 2 Month 12 Innovation Management – The innovation strategy and IPM’s strategy are revised in the light of the achievements of the development phase: the portfolio has expanded, operational results have been recorded, simulations and cross-functional tests have revealed new imperatives. Updating innovation and IPM strategies is part of the maintain innovation strategy component. Its objectives are to prepare the next phase of scaling up the IPM process, to feed the communication plan announcing this phase, to integrate the contributions of the previous stages, to take into account the movements of the competition and the markets targets, and to enhance the operational results obtained at the end of recently completed innovation projects. For example, as IPM’s strategy depends on the maturity of the innovation process in its scope of application, it was able to evolve at the same time as said process. 5 levels of ambition are proposed for the IPM strategy: detection, measurement, prioritization, openness and acquisition strategy. Each level corresponds to simple criteria for assessing the maturity of the innovation process, such as the identification of at least one proven or projected hyper-growth activity, the deployment of IPM software facilitating open innovation with a deep ecosystem, the success rate of the innovation projects in the portfolio, the level of involvement of the sales functions or the rate of conclusion of innovative partnerships. The innovation strategy is itself tuned according to the levels of success recorded and new prospects identified, for example the rate of penetration of targeted niche markets, changes in projected, ongoing or proven economic models design, a rate of automation on a perimeter considered strategic, or measures of competitive advances on offerings with high potential.

High-Performance Innovation – Part 3 – Year 3

- Part 3 Month 1 Customer Voice – The first building block of an innovation portfolio management process is the organization’s connection to representatives of its ecosystem. Indeed, it is illusory to hope to create value by innovating without having first surveyed its target markets, its potential partners, its own employees and colleagues and sometimes the regulators (in particular when the ambition of an innovation is to societal scope, with a strong impact on the ecosystem). It is certainly possible to be lucky and to succeed with the only mobilization of your flair, but on a large scale the statistics are against this type of approach. Also the process of IPM must rely on a network of correspondents, market witnesses, with whom ideas and approaches are tested at the right time, that is to say before the investments are so important and the development so advanced that it is no longer possible to call into question a project in progress. This supposes having meshed the organization with privileged contacts of these witnesses. Their skills include network management, online community animation, meeting facilitation, agile methods and knowledge of the key professions involved in current innovation projects. Their qualities include empathy, ability to synthesize, curiosity, creativity and rigor. They apply a 4-step method that has proven itself in fifteen different professions. A shared repository hosts the results of the innovation sessions, accessible to the teams involved in the scope considered. Only the summaries of these results are available for witnesses outside the organization, for purposes of animation and reward for the efforts made. These summaries form a forum-type discussion base and never contain any trade secrets.