Change Resilience – Workshop 4 (Emotional Intelligence)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Change Resilience is provided by Ms. Aikerson Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Ms. Aikerson is a Certified Learning Provider (CLP) with Appleton Greene and a highly sought-after speaker, trainer, coach, and consultant. She has a remarkable ability to simplify complex concepts, designing programs that deliver immediate and lasting results. Her approach to learning is engaging, actionable, and impactful, ensuring participants walk away with practical strategies they can apply right away.

With extensive experience across a diverse range of industries—including Aviation, Government, Financial Services, Manufacturing, Consumer Goods, Pharmaceuticals, Consultancy, Insurance, Food & Beverage, Telecommunications, Transportation, and Construction—Ms. Aikerson helps organizations successfully navigate change and transformation. By integrating principles of human psychology, she equips leaders and employees with the tools they need to adapt, ensuring measurable improvements in key business metrics and performance outcomes.

Her impressive academic background includes a Change Management Certificate from Harvard University, an MBA from Northwestern University, and a degree in Electrical Engineering from Bradley University. She also holds multiple certifications, including Prosci ADKAR Change Management, DISC Personality Traits, Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), Emotional Intelligence, Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), and Six Sigma (Green Belt), among others.

A dedicated leader in her field, Ms. Aikerson has served as chapter president for several professional organizations, including the National Technical Association (NTA), the Association for Women in Communications (AWC), and Tomorrow’s Scientists, Technicians, and Managers (TSTM).

Her passion for empowering individuals and organizations to thrive in change continues to make her an influential force in professional development and organizational success.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

Part 1 Month 4 Emotional Intelligence – Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a critical skill for navigating change and fostering a resilient, adaptive organization. In this session, you will explore how strong emotions often arise when change is introduced and learn strategies to manage these emotions effectively. Developing EI as an organizational norm allows for healthier communication, stronger relationships, and better decision-making under pressure. You will gain practical tools to recognize and regulate emotions—both your own and those of others—ensuring that emotional reactions do not derail progress or collaboration. Additionally, you will learn techniques to navigate emotional landmines, addressing conflicts and challenges with self-awareness, empathy, and composure. By the end of this session, you will have a deeper understanding of how to meet emotional challenges with intelligence, respond thoughtfully rather than react impulsively, and create an emotionally resilient workplace where individuals feel heard, valued, and understood.

Objectives

01. Understanding Emotional Triggers: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. The Five Components of Emotional Intelligence: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Emotional Hijacking and Recovery: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Empathy in Action: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Emotional Tone in Communication: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Cultivating Self-Awareness in Real Time: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Regulating Emotions Under Pressure: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Emotional Contagion in the Workplace: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Difficult Conversations with Emotional Intelligence: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Building Emotional Safety in Teams: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Measuring Emotional Intelligence: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Embedding EI into Culture: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Understanding Emotional Triggers: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. The Five Components of Emotional Intelligence: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Emotional Hijacking and Recovery: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Empathy in Action: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Emotional Tone in Communication: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Cultivating Self-Awareness in Real Time: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Regulating Emotions Under Pressure: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Emotional Contagion in the Workplace: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Difficult Conversations with Emotional Intelligence: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Building Emotional Safety in Teams: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Measuring Emotional Intelligence: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Embedding EI into Culture: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Understanding Emotional Triggers.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse The Five Components of Emotional Intelligence.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Emotional Hijacking and Recovery.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Empathy in Action.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Emotional Tone in Communication.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Cultivating Self-Awareness in Real Time.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Regulating Emotions Under Pressure.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Emotional Contagion in the Workplace.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Difficult Conversations with Emotional Intelligence.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Building Emotional Safety in Teams.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Measuring Emotional Intelligence.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Embedding EI into Culture.

Introduction

Organizational transformations invariably evoke a broad range of emotional reactions among employees and stakeholders. While strategic plans, process blueprints, and technological enablers form the structural bedrock of change initiatives, the emotional landscape often determines whether those plans take root or falter. During periods of upheaval—whether triggered by a merger, a large-scale system rollout, or a major restructuring—individuals may experience eager anticipation at the prospect of new opportunities, yet simultaneously feel apprehension about potential disruptions to established routines. For some, change can provoke resistance or even grief, particularly when roles shift, familiar processes vanish, or uncertainties loom large. These emotional currents, if left unacknowledged, have the power to undermine the best‐designed transformation efforts by eroding engagement, sapping morale, and fragmenting trust.

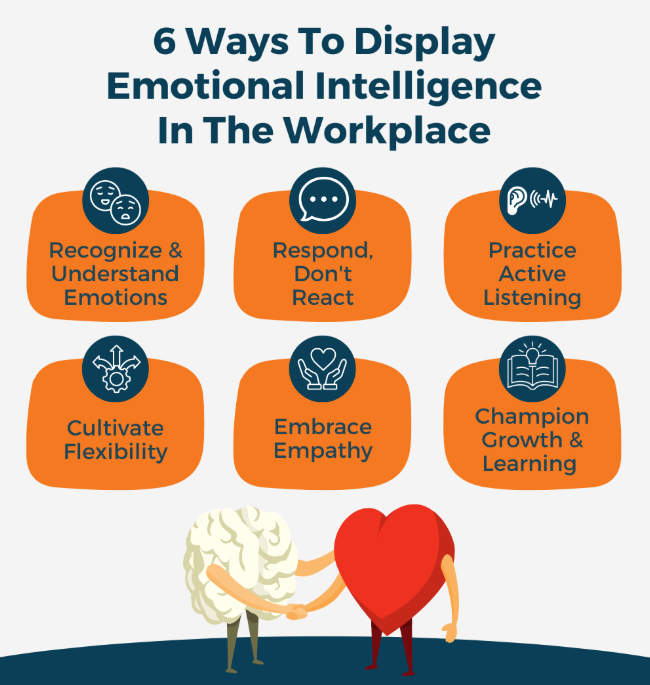

In response to these challenges, emotional intelligence (EI) emerges as a critical capability for organizations seeking to build enduring resilience. At its core, EI encompasses the ability to recognize and understand one’s own feelings as they arise, to regulate and channel those emotions constructively, and to perceive and empathize with the emotional states of colleagues. When cultivated as an organizational norm, EI fosters the psychological safety required for candid dialogue: individuals feel both heard and valued, even when conversations touch on uncomfortable topics. This environment of mutual respect encourages team members to voice concerns, share innovative ideas, and surface potential roadblocks—precisely the kind of open communication that prevents small issues from metastasizing into full‐blown crises.

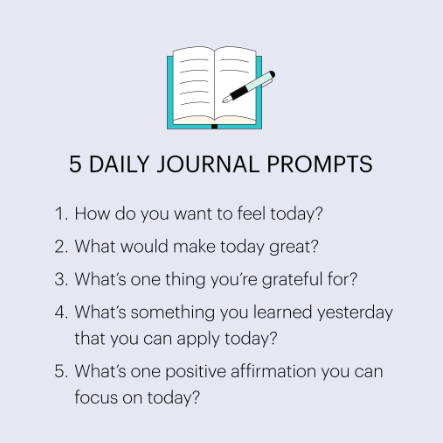

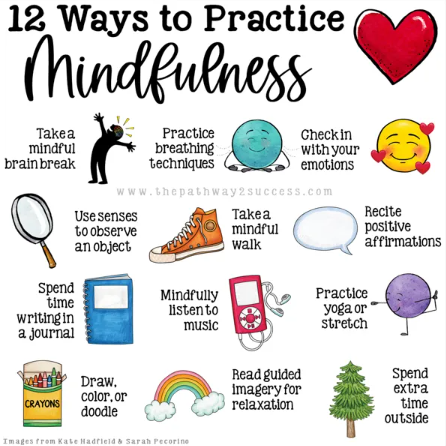

Developing EI as a foundational competency during change involves more than a one-off training session. It requires embedding practices that enhance self‐awareness—such as reflective journaling or pulse‐check assessments—so that individuals become attuned to their own stress triggers and emotional patterns. Equally important is the skill of self‐regulation: learning to pause before reacting, choosing thoughtful responses over impulsive reactions, and cultivating strategies (breathing exercises, brief mindfulness breaks, or simple reframing techniques) that prevent emotional overwhelm from derailing collaborative progress. In parallel, competencies such as empathy and active listening equip leaders and teammates to interpret the subtle cues of frustration or anxiety in others—allowing them to address concerns early, validate emotions without judgment, and guide conversations toward constructive problem‐solving rather than blame.

By weaving EI into everyday routines— team huddles that begin with a brief emotional check‐in, coaching conversations that balance task guidance with personal support, and leadership forums that model vulnerability—organizations signal that emotions are neither a sign of weakness nor a distraction, but rather a vital source of information. When emotions are acknowledged openly, individuals feel safer taking calculated risks, experimenting with new approaches, and offering divergent perspectives. Over time, this culture of emotional attunement yields three key outcomes: healthier communication (fewer misunderstandings and less unspoken tension), stronger relationships (built on empathy and mutual respect), and more effective decision‐making under pressure (because emotional cues—such as signs of burnout or frustration—are detected and addressed proactively).

The Case for Emotional Intelligence in Change

Change initiatives frequently amplify underlying stressors—shifting expectations, ambiguous responsibilities, and uncertain outcomes—that bring latent anxieties and interpersonal frictions to the surface. As plans for restructured processes or reorganized teams ripple through an organization, individuals often experience anticipatory anxiety, worrying about potential skill gaps, altered career trajectories, or threats to job security. Even when changes promise long-term benefits, the departure from familiar routines, legacy systems, or established working relationships can trigger a sense of loss akin to grief. In these moments, people may cycle through stages of denial or bargaining—resisting new tools or procedures—before eventually accepting the evolution of their roles. Simultaneously, identity threats can emerge: professionals whose responsibilities have shifted may question their competence or sense of purpose, leading some to withdraw from collaboration or second-guess their contributions. These internal struggles do not remain isolated; they frequently spill over into team dynamics, reigniting buried resentments or reinforcing silo mentalities as individuals seek protection from perceived emotional threats.

This complex emotional landscape underscores the imperative of emotional intelligence (EI) for fostering organizational resilience. Unlike approaches that treat change as a purely tactical or procedural challenge, an emotionally intelligent response acknowledges that human beings are at the heart of transformation. By cultivating self-awareness, leaders and team members become attuned to their own stress signals—such as increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, or emotional exhaustion—and can intervene before these signs undermine performance. Empathy extends this awareness outward: when colleagues recognize that peers may be wrestling with loss, uncertainty, or identity concerns, they can proactively offer validation and support rather than inadvertently dismissing anxieties as mere resistance. As a result, open channels of communication replace silent suffering, enabling underlying issues—“I feel out of depth with this new software,” or “I’m worried my role no longer matters”—to be surfaced and addressed early.

Empirical research consistently links higher levels of EI with enhanced adaptability. Individuals who practice emotional regulation techniques—such as reframing a stressful deadline as an opportunity to develop new problem-solving skills—maintain curiosity and a growth orientation rather than capitulating to fear. This mindset shift not only accelerates learning but also reduces the likelihood of burnout, as employees view challenges as manageable rather than insurmountable. Moreover, EI-driven empathy fosters collaboration by building trust: when teammates feel understood, they are more inclined to share ideas honestly, admit mistakes, and co-create solutions, rather than retreating into defensiveness or silence. Decision-making also benefits: by recognizing and tempering strong emotions—be it frustration, excitement, or fear—leaders avoid reactive judgments that prioritize short-term relief over sustainable outcomes. Instead, they can deliberate thoughtfully, balance data with human considerations, and arrive at choices that reflect both strategic objectives and people’s concerns.

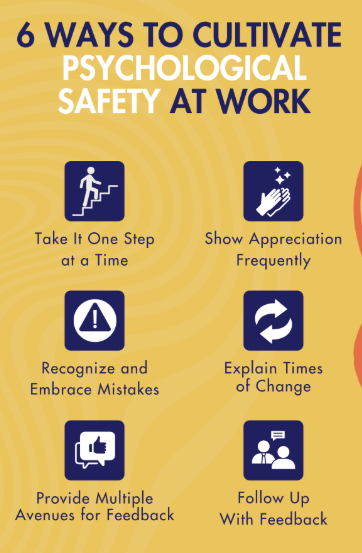

Finally, emotional intelligence lays the groundwork for psychological safety—a critical enabler of innovation and long-term resilience. In environments where emotional dynamics are acknowledged and respected, employees feel safe to raise difficult questions (“What if this approach fails?”), voice dissenting perspectives (“I’m not convinced we’ve accounted for all risks”), and propose novel ideas without fearing ridicule or punishment. This climate of mutual respect and open dialogue prevents social tensions from calcifying into entrenched conflicts, instead channeling diverse viewpoints into healthy debate and creative problem-solving. As a result, organizations that prioritize EI do not merely weather change more effectively; they transform emotional turbulence into a source of collective strength, ensuring that transitions become springboards for growth rather than stumbling blocks to progress.

Defining Emotional Intelligence

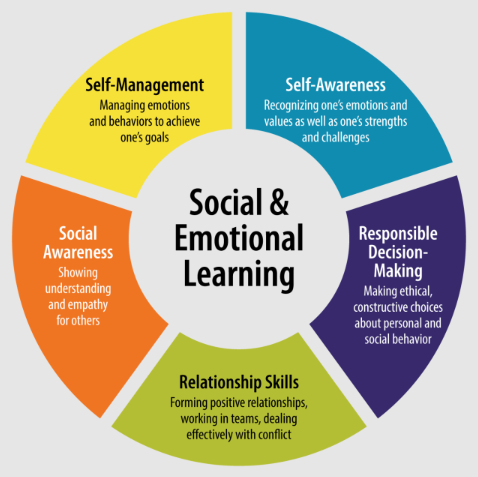

Emotional intelligence, broadly defined, refers to the capacity to recognize, understand, and manage one’s own emotions, as well as to perceive, interpret, and influence the emotions of others. Although conceptualized differently across models, most frameworks converge on four core dimensions:

Self-Awareness:

• Emotional Recognition: The ability to accurately identify one’s emotions as they arise (e.g., noticing a surge of frustration when plans change).

• Self-Reflection: Exploring the root causes and patterns behind emotional responses—why certain stimuli trigger defensiveness, impatience, or enthusiasm.

• Impact Awareness: Understanding how one’s emotions and behaviors affect others (e.g., realizing that terse emails during stress may demoralize colleagues).

Self-Regulation:

• Impulse Control: Redirecting strong emotional impulses (anger, fear) into constructive strategies—pausing before reacting, breathing techniques, or reframing negative thoughts.

• Mindful Response: Choosing well-considered actions aligned with values and long-term goals, rather than being hijacked by immediate feelings.

• Resilience Practices: Cultivating habits (journaling, brief mindfulness breaks) that neutralize stress and sustain emotional equilibrium under pressure.

Empathy (Social Awareness):

• Perspective-Taking: Actively seeking to understand colleagues’ feelings and motivations—imagining how a direct report might perceive a sudden shift in priorities.

• Emotional Cue Recognition: Observing verbal tone, body language, and micro-expressions that signal unspoken distress, skepticism, or enthusiasm.

• Cultural Sensitivity: Appreciating how diverse backgrounds shape emotional norms—some cultures openly express frustration; others suppress it to preserve group harmony.

Relationship Management:

• Constructive Communication: Framing feedback and directives in ways that acknowledge emotional states—“I know this new process can feel overwhelming; let’s discuss concerns before we proceed.”

• Conflict Resolution: Navigating disagreements by validating emotions (“I hear your frustration”) before addressing underlying issues, thereby defusing tension.

• Motivational Influence: Leveraging emotional insights to inspire action—recognizing that some individuals respond to personalized encouragement while others prefer data-driven rationale.

The Neuroscience of Emotion in Change

Understanding the brain’s emotional architecture sheds light on why emotions so powerfully shape change experiences. Although not a prerequisite for developing EI, a neuroscience primer underscores the physiological basis for emotional intelligence competencies.

The Limbic System and the “Emotional Hijack”:

• Amygdala Activation: The amygdala acts as an early warning system, reacting to perceived threats (e.g., the threat of obsolescence when new technology arrives). This can trigger a “fight, flight, or freeze” response before the rational brain (prefrontal cortex) engages.

• Prefrontal Cortex Regulation: EI involves strengthening pathways between the prefrontal cortex (responsible for executive functions and reasoning) and the amygdala, allowing individuals to notice emotional arousal and choose measured responses rather than succumbing to knee-jerk reactions.

Neuroplasticity and EI Development:

• Habit Formation: Regular practices—such as pausing to label an emotion (“I feel anxious because my role is shifting”)—recruit neural networks that, over time, make self-awareness and self-regulation more automatic.

• Empathy Circuits: Mirror neurons in the brain facilitate empathy by internally simulating others’ emotional states. Engaging in perspective-taking exercises during change deepens these neural connections, enhancing social awareness.

Stress Hormones and Decision-Making:

• Cortisol Build-Up: Prolonged stress elevates cortisol levels, impairing cognitive flexibility and fostering narrow, survival-focused thinking. Emotional intelligence strategies—brief mindfulness breaks or physical movement—lower cortisol, preserving executive functioning essential for complex change decisions.

Developing Self-Awareness in Change Contexts

Developing self-awareness during periods of change begins with cultivating the capacity to recognize and articulate one’s own emotional states as they arise. This foundational skill serves as the essential first step in any broader emotional intelligence journey, as unrecognized emotions can unconsciously drive reactions—sometimes counterproductive—during critical moments. By practicing deliberate techniques for noticing, labeling, and reframing emotions, individuals create a mental space between stimulus and response, allowing for more purposeful choices rather than impulsive reactions. The following subsections describe effective approaches to strengthen self-awareness in the midst of organizational transformations.

Emotional Labeling Practices:

At the heart of emotional labeling is the simple yet powerful principle often summarized as “name it to tame it.” When strong feelings surface—whether that is irritation simmering during a tense stakeholder meeting, anxiety rising as a new deadline looms, or even excitement mixed with trepidation before a major rollout—pausing to assign a precise label (for example, “I feel frustrated” or “I feel anxious”) engages the brain’s prefrontal cortex. This labeling moment shifts activity away from the amygdala’s fight-or-flight response, creating a brief window in which thoughtful reflection can occur.

To embed this practice into daily routines, a structured “emotional check-in” ritual can be introduced. At predetermined intervals—such as the start of the workday, immediately following lunch, and at day’s end—individuals pause for a minute to scan their internal landscape, noting what they feel. A simple numerical scale (1 signifying very calm to 5 signifying highly stressed) or short descriptive tags (e.g., “overwhelmed,” “motivated,” “uncertain”) can be recorded in a journal or digital log. Over time, patterns emerge: perhaps midweek status meetings consistently spike frustration, or after project milestones anxiety subsides and hopefulness returns. By documenting these emotional trends alongside situational notes, change leaders and team members gain insight into recurring triggers—whether ambiguous communication, resource bottlenecks, or evolving role clarity—and can proactively design interventions (such as clarifying documentation or scheduling supporting check-ins) to mitigate negative emotional cascades before they interfere with productivity or morale.

Cognitive Distortions and Reframing:

Change can amplify automatic, negative thought patterns—often called cognitive distortions—that magnify stress and undermine self-confidence. A common example is catastrophizing, in which an individual leaps to worst-case conclusions (“If this pilot fails, I’ll be blamed”). Other frequent distortions include all-or-nothing thinking (“If I don’t master this new system immediately, I’m incompetent”) and personalization (“Because my team missed the target, they must think I’m not pulling my weight”). These distorted beliefs act like emotional traps, intensifying fear and narrowing one’s ability to consider alternative perspectives.

Developing self-awareness in this context involves first learning to identify such distortions as they occur. One method is to pause at the moment of distress and ask, “What evidence supports this thought? What evidence contradicts it?” If the belief is “Everyone will see me as a failure,” one might note that previous setbacks did not result in ostracism, or that colleagues have expressed appreciation for one’s contributions. Another useful prompt is, “What would I tell a colleague feeling this way?” By deliberately challenging distorted beliefs—replacing “This pilot defines my entire career” with “This project is one data point in a broader track record”—individuals begin to shift from reactive emotional reactivity toward measured, balanced appraisal. Over repeated practice, reframing becomes more automatic, reducing the intensity of emotional volatility and equipping individuals to maintain composure during high-pressure junctures.

360° Emotional Feedback:

While self-observation is critical, it can overlook blind spots—those aspects of one’s emotional display that others perceive but the individual does not. Incorporating structured feedback channels allows these blind spots to surface, further deepening self-awareness. One approach is to deploy brief “pulse surveys” that gauge the team’s collective emotional climate. For example, anonymous weekly surveys might ask each member to rate how supported, informed, or stressed they felt in the past week. Aggregated results can reveal discrepancies between leadership’s perception of overall calm and the team’s experience of uncertainty.

In addition to surveys, structured peer check-ins offer a more qualitative, nuanced window into emotional dynamics. During regular one-on-one or small-group meetings, peers can be invited to share observations about emotional patterns: “I noticed you seemed unusually tense during yesterday’s planning session—was there something on your mind?” By framing these inquiries from a supportive, curious standpoint rather than as criticism, individuals receive candid insights that complement their own self‐reports. This collaborative feedback loop not only surfaces unrecognized stress signals—such as a furrowed brow or terse tone—but also models the vulnerability and openness that underpin a culture of emotional intelligence.

Taken together, emotional labeling, cognitive reframing, and 360° feedback constitute an integrated toolkit for developing self-awareness in change contexts. As individuals become adept at noticing their emotional states in real time, challenging unhelpful thought patterns, and inviting constructive criticism from trusted peers, they build a foundation for more effective regulation and empathetic engagement. Over time, this heightened self-awareness transforms reactive behaviors into thoughtful responses, enabling both leaders and teams to navigate the emotional turbulence of transformation with greater agility and resilience.

Mastering Self-Regulation Under Pressure

Mastering self‐regulation under pressure involves transforming intense emotional impulses into measured, constructive actions rather than allowing fear, frustration, or overwhelm to drive hasty or counterproductive decisions. In the midst of organizational change, when timelines compress and uncertainty heightens, the capacity to remain composed becomes a strategic advantage. Leaders and team members who demonstrate calm under fire model resilience for others, anchoring the group’s emotional climate and preventing small stressors from spiraling into performance‐derailing crises.

One foundational approach to emotional de‐escalation is the integration of micro‐mindfulness practices into daily routines. These micro‐practices—such as pausing for two minutes of focused, diaphragmatic breathing; conducting a quick, inward‐focused body scan while sitting at one’s desk; or stepping outside briefly to feel fresh air—serve as intentional interruptions to the physiological stress response. When the brain registers an immediate threat, the amygdala triggers a cascade of cortisol, preparing the body for fight‐or‐flight. A short mindfulness exercise activates the prefrontal cortex, restoring executive function and creating a momentary space in which more thoughtful choices become available. For instance, during a heated status meeting where unfamiliar metrics spark anxiety, a leader might silently focus on the sensation of their breath for two cycles, giving themselves the lateral distance needed to craft a calm, clarifying question rather than reacting defensively.

Complementing these micro‐practices are anchor techniques—simple, personally meaningful affirmations that reorient attention toward agency and possibility. An anchor statement such as “This challenge is significant, but I have navigated complexity before” functions as a cognitive touchstone, reminding the mind to move from reactive self‐judgment (“I can’t handle this”) toward proactive problem‐solving (“What is one step I can take right now to move forward?”). Repeating such an anchor silently when emotions intensify interrupts the negative feedback loop of catastrophic thinking, transforming raw emotional energy into focused intention. Over time, these anchor statements become habitual, allowing individuals to automatically deploy a stabilizing mantra whenever they detect rising tension—whether that tension arises from a critical stakeholder’s pushback or an unexpected iteration in a project plan.

Impulse control also lies at the heart of effective self‐regulation during change. Rather than succumbing to the urge to deliver an immediate rebuttal after receiving a harsh critique in a meeting, high‐EI practitioners follow a “Pause, Perspective, Proceed” approach. First, they pause to notice the bodily cues of escalating stress—perhaps a clenched jaw or a racing pulse. Next, they consider perspective: “What is the outcome I want? Do I wish to escalate conflict, or do I wish to foster understanding and move the project forward?” By evaluating the long‐term goal versus the short‐term emotional urge, the individual reframes the choice. Finally, they proceed with a calm, measured response—such as requesting a brief break, asking clarifying questions, or acknowledging the feedback before offering a thoughtful reflection. This structured pause prevents the typical impulse‐driven reactions—snapping back or withdrawing entirely—and encourages a response aligned with both personal values and organizational objectives.

Similarly, adopting a delayed response protocol for emotionally charged communications—such as an email that feels accusatory or a discouraging project update—reinforces reflective processing. By instituting a rule to wait a minimum of 30 minutes before drafting a reply, one allows the initial surge of adrenaline to subside. During the waiting period, the individual might revisit the anchor statement or discuss the situation with a trusted colleague, seeking alternative interpretations or pragmatic next steps. This buffer not only attenuates emotional bias but also opens the door for more constructive dialogue: the eventual response is likely to be calmer, more solution‐oriented, and less prone to perpetuate conflict.

However, self‐regulation is not merely about moment‐to‐moment tactics; it is also rooted in broader resilience‐building habits that fortify one’s capacity to cope with sustained pressure. Scheduling regular reflection time—ten to fifteen minutes, two or three times a week—encourages journaling about recent emotional challenges and the lessons gleaned. Writing prompts might include: “Identify a moment this week when you felt overwhelmed. What triggered the emotion, and what did you do to regain composure?” or “Recall a time when an anchor statement helped you navigate stress. How might you refine that statement for the future?” These reflective practices reinforce self‐awareness, track progress over time, and crystallize personal strategies that work in real change scenarios.

Equally vital is attention to physical well‐being, which underpins emotional resilience. Adequate sleep, balanced nutrition, and moderate exercise help regulate hormones and neurotransmitters that govern mood, energy, and cognitive function. Even within a demanding workday, brief stretches between virtual meetings or standing meetings help break the cycle of sedentary stress. By integrating these healthy routines into the organizational culture—such as encouraging walking meetings or providing quick stretch‐break prompts—teams collectively benefit from lowered cortisol levels and sustained focus.

Mastering self‐regulation under pressure requires a combination of immediate interventions (micro‐mindfulness, anchor statements, delayed response protocols) and ongoing resilience practices (scheduled reflection, physical well‐being routines). As organizations navigate complex transformations, individuals who practice these techniques not only protect their own equilibrium but also serve as stabilizing influences for their colleagues. By channeling emotional energy into constructive action rather than reactive impulses, teams maintain momentum, model resilience, and cultivate the psychological safety needed for sustained adaptability.

Cultivating Empathy and Social Awareness

Empathy and social awareness form the heart of constructive team dynamics, especially during periods of transformation when emotions run high and uncertainty colors every interaction. Recognizing and validating the feelings of others not only builds trust but also fosters a culture where individuals feel heard and supported. One fundamental practice is active listening, which demands full presence in every conversation. This means temporarily silencing email notifications, closing unrelated tabs, and maintaining consistent eye contact—or in virtual settings, centering the camera view on the speaker. By giving undivided attention, change leaders and colleagues signal respect and openness, encouraging honest dialogue even when the topics feel difficult.

Within active listening, reflective responses serve as powerful tools for confirming understanding. Rather than immediately reacting to a colleague’s concern—such as frustration over shifting deadlines—one paraphrases the essence of their statement: “It seems you’re troubled by how the new timeline may affect our quality standards.” Such reflection demonstrates genuine comprehension and invites further clarification, ensuring that misinterpretations do not festoon the conversation. Alongside paraphrasing, emotional labeling extends this validation by naming the inferred emotion: “It sounds like you’re feeling frustrated by the lack of resources.” By articulating the underlying emotion, the listener validates the speaker’s internal experience rather than dismissing it, strengthening mutual empathy.

Perspective‐taking exercises deepen social awareness beyond momentary exchanges. In role‐reversal scenarios, small groups simulate one another’s positions to feel firsthand the pressures colleagues face—asking, for example, “As the operations lead, how do you perceive the pressure to cut corners on testing?” This exercise heightens sensitivity to others’ emotional strains and fosters shared understanding. Similarly, structured empathy interviews encourage team members to speak one‐on‐one with peers outside their direct reporting lines, exploring how the change affects them personally—their anxieties, aspirations, and doubts. Summarizing these interviews anonymously creates a “collective emotional map,” revealing common concerns and guiding targeted support interventions.

Reading emotional cues further enhances social awareness. In face‐to‐face settings, observable signals—crossed arms, pacing, or facial tension—often betray unspoken worry or resistance. In virtual meetings, subtler indicators emerge: fading attention, delayed responses, or changes in tone and pacing. When these cues surface, attentive listeners can gently invite elaboration: “I noticed you were quieter than usual during the discussion; is there something on your mind?” Additionally, periodic group sentiment checks—conducted at critical milestones such as project kickoffs, midpoint reviews, or post‐launch reflections—ask each participant to rate their sense of support on a scale. Using anonymous polling tools ensures candor and surfaces emerging tensions before they escalate, giving leaders an early warning system for addressing collective emotional undercurrents.

Responding to Emotional Landmines:

Even in organizations committed to emotional intelligence, unanticipated conflicts, perceived slights, or cascading stress can create “emotional landmines” that threaten to derail both relationships and project outcomes. Navigating these minefields effectively requires a combination of de‐escalation tactics, restorative practices, and clear boundary setting. One core de‐escalation strategy involves explicitly naming the tension. When frustration flares—such as evident irritation over shifting deadlines—an effective leader acknowledges it aloud: “I sense there’s frustration around our evolving timeline. Let’s pause and explore what’s driving that feeling.” By naming the emotion, the tension loses its covert power and invites open discussion.

Separating the person from the issue helps prevent conflicts from becoming personal attacks. Instead of saying, “You’re being reckless with these shortcuts,” a more constructive approach is to frame the concern in terms of impact: “I’m worried that reducing our testing cycles might compromise product quality.” This reframing focuses criticism on actions rather than character, preserving relationships while still addressing the issue. To prevent heated discussions from spinning out of control, teams can agree on a “time‐out” phrase—such as “Let’s park this”—which any member may invoke to halt the conversation temporarily. This shared signal creates a safe space for emotions to cool before resuming dialogue with greater composure.

When emotional landmines do explode into conflict, restorative conversations offer a path to repair and rebuild trust. These dialogues begin with affective statements in which participants express personal impact using “I” language: “I felt overlooked when my question wasn’t addressed in yesterday’s meeting.” By framing the issue as a personal experience rather than assigning blame, individuals open the door to mutual understanding. Affective questions—such as “How do you feel this change affects your team’s morale?”—invite deeper exploration of emotions and help both parties appreciate each other’s perspectives. Conducting restorative conversations in one‐on‐one or small‐group settings encourages candid sharing. A typical structure might progress through acknowledgment of impact (“I realize my announcement was abrupt and caused stress”), an expression of regret (“I’m sorry I didn’t explain the reasoning more clearly”), and a commitment to change (“Next time, I will share the bigger picture and check for concerns before finalizing decisions”). This guided process transforms conflict into an opportunity for relational growth.

Beyond de‐escalation and restoration, boundary setting provides a preventative layer of support. Clarifying and reinforcing role definitions helps prevent friction born of overlapping responsibilities. When disputes arise over who “owns” a task, referring back to updated charters or role matrices can clarify expectations and reduce friction. In parallel, offering emotional support resources—such as access to internal or external coaches, employee assistance programs, or peer‐support groups—signals organizational commitment to well‐being. Normalizing these resources reduces stigma; leaders might say, “Many of us seek extra perspective during transitions. Here’s a confidential resource you can turn to.” When individuals know that emotional aid is readily available and accepted, the threshold for seeking help lowers, preventing small stressors from metastasizing into larger crises.

Together, these practices of cultivating empathy, honing social awareness, and navigating emotional landmines form a comprehensive approach to sustaining emotional intelligence during change. By listening actively, validating others’ experiences, and intervening when tensions arise, organizations create an environment where emotions fuel constructive dialogue rather than destructive friction. This emotional infrastructure underpins resilience, enabling teams to weather uncertainty, innovate collaboratively, and maintain momentum throughout transformation.

Embedding Emotional Intelligence into Organizational Culture

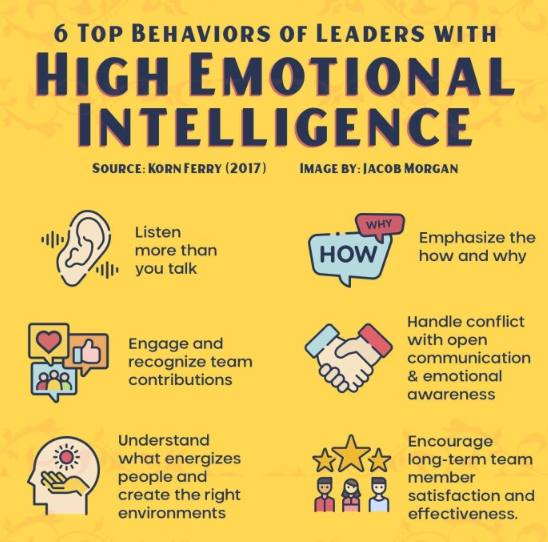

Embedding emotional intelligence (EI) into an organization’s daily routines transforms it from a one-off training topic into a sustained cultural capability. Central to this integration is leadership modeling: when executives openly share their own emotional challenges and coping strategies, they normalize vulnerability and signal that emotional awareness is valued. For example, a senior leader might describe feeling uncertain during a recent restructuring and outline the steps taken to manage those feelings—demonstrating that even those at the top experience and navigate emotional responses. This transparency reduces stigma and encourages employees to voice concerns and seek support.

Complementing modeling, regular “Emotional Pulse” forums provide structured opportunities for collective reflection. Held quarterly or at key project milestones, these sessions present anonymized mood-survey results or narrative summaries of team sentiment. By discussing emerging stressors and brainstorming resilience strategies together, participants reinforce that monitoring emotions is integral to execution—no less important than budget reviews or performance metrics.

Embedding EI into performance and development processes further solidifies its importance. Review criteria should include self-awareness, empathy, and conflict-resolution skills alongside technical goals. Questions such as “How did you recognize and address a colleague’s stress signals last quarter?” ensure that emotional competencies are assessed and rewarded. Public recognition—through awards or career advancement—underscores that demonstrating EI is a pathway to professional success.

To institutionalize these practices, some organizations establish dedicated roles or rotating committees of “Change Empathy Advocates.” Charged with facilitating EI workshops, conducting mood pulse checks, and offering peer coaching, these advocates keep emotional well-being on the agenda. Their visible presence conveys a long-term commitment to EI, moving beyond checkbox compliance to ongoing stewardship of organizational health.

Sustaining EI development also relies on continuous learning opportunities. Micro-learning modules—brief videos or written prompts accessible via digital collaboration platforms—allow staff to revisit EI concepts just when they’re needed, such as during a high-stress launch. Parallel to this, peer-coaching circles bring together small, cross-functional groups monthly to share recent emotional experiences—like managing frustration over shifting priorities—and exchange coping strategies. These circles foster accountability and normalize the habit of checking in on one another’s well-being.

Finally, integrating emotional check-ins into existing team rituals ensures that EI remains woven into operations. A sprint retrospective might begin with “How did this week land emotionally?” alongside standard process questions, surfacing concerns that inform future planning. Similarly, brief guided breathing exercises at the start of planning sessions create a collective moment of calm, preparing participants for focused collaboration. Over time, these ritualized practices build a resilient culture in which emotional intelligence is not optional but foundational to navigating continuous change.

Embedding Emotional Intelligence into Organizational Systems and Practices

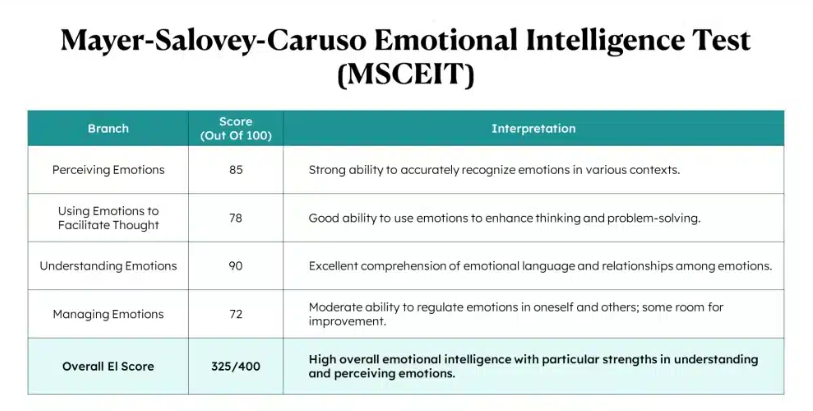

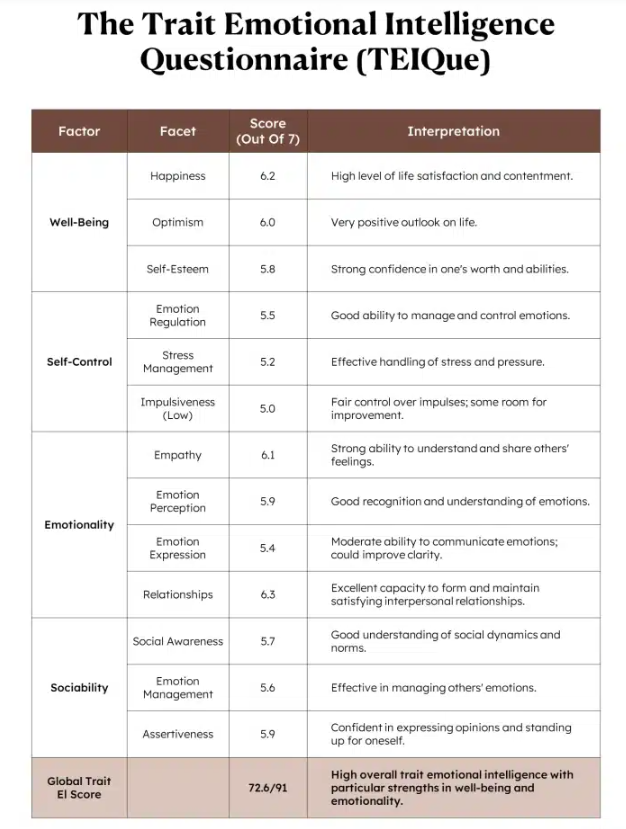

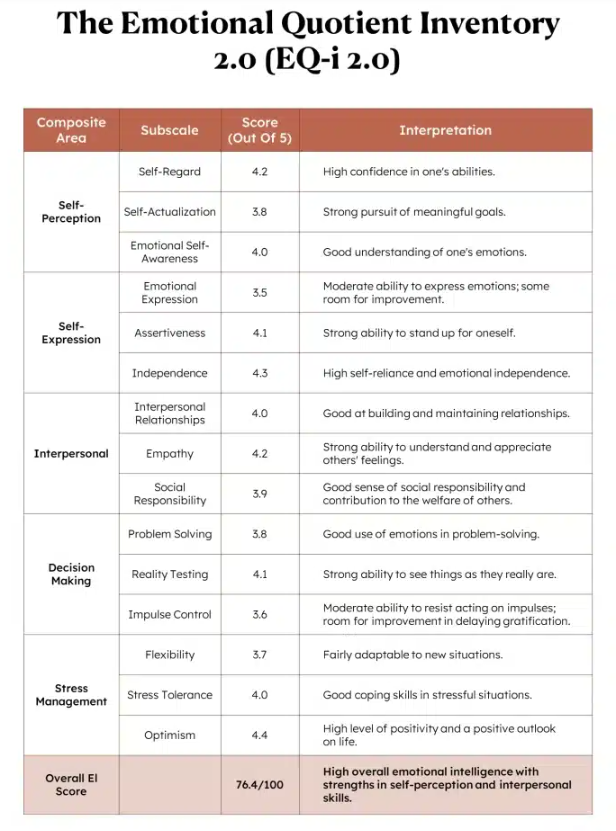

Measuring Emotional Intelligence Impact: Assessing the effectiveness of emotional intelligence (EI) initiatives is crucial for validating their value and guiding continuous improvement. A comprehensive measurement approach blends quantitative pulse surveys, behavioral indicators, business outcomes, qualitative feedback, and practical exercises to create a multidimensional view of EI’s role in change resilience.

Pulse Surveys and Climate Metrics: Short, regular pulse surveys capture the team’s emotional climate by asking targeted questions such as “I feel comfortable voicing concerns in meetings” or “Leadership understands my emotional state during change.” Tracking these scores weekly or biweekly reveals trends in psychological safety. An upward trajectory indicates growing trust, while sudden dips highlight emerging stressors. Including stress and burnout questions—“On a scale of 1–5, how overwhelmed have you felt this week?”—identifies at-risk individuals or teams before performance suffers.

Behavioral Indicators: Self-reports are complemented by observable behaviors. A reduction in formally reported conflicts—escalations to HR or internal ombuds—signals improved conflict-management skills. Collaboration quality metrics, such as fewer project delays due to interpersonal friction or faster dispute resolution, show that emotional competencies are translating into smoother teamwork.

Business Outcomes Correlation: Comparing project cohorts with and without EI support clarifies its impact on hard metrics: higher change-adoption rates, fewer rework cycles, and reduced help-desk tickets all point to more effective communication and training. Engagement and retention figures further reinforce EI’s value—teams receiving robust EI training often report higher engagement scores during transitions and exhibit lower turnover, demonstrating that emotional support drives both performance and loyalty.

Qualitative Feedback and Storytelling: Focus groups and narrative capture add nuance to survey data. Facilitated discussions probe questions like “When did you feel most supported emotionally during this transition?” and “What additional EI resources would have helped?” These forums uncover subtle cultural blind spots and surface ideas for new interventions. Teams also collect “EI success stories”—brief anecdotes of empathetic listening or reframing that prevented setbacks—building a repository of lived examples to reinforce best practices.

Practical EI Practices: Embedding simple exercises into daily routines ensures that EI remains a lived capability. An Emotional Diary prompts individuals to log three highs and lows each day along with triggers. Weekly anonymous syntheses highlight recurring stress points—say, anxiety around resource discussions—so leadership can address root causes in retrospectives. The Pause & Reflect Protocol inserts brief silent pauses at the start and end of meetings for emotional check-ins, normalizing self-awareness and reducing reactive behavior. Empathy Mapping Workshops guide teams through “Says/Thinks/Feels/Does” exercises for different stakeholders, deepening social awareness and informing targeted support. Finally, Guided Reframing Sessions turn negative narratives—“This new system is pointless”—into constructive alternatives, shifting collective mindsets toward opportunity and learning.

Together, these quantitative and qualitative measures, coupled with embedded practices, create a feedback-rich environment. Leaders can see how EI interventions enhance trust, collaboration, and adaptability, and continually refine their approach to build an emotionally resilient organization.

Case Study: Microsoft’s Cultural Renewal under Satya Nadella

By 2014, Microsoft had achieved global dominance but faced cultural stagnation: risk aversion, internal competition, and declining morale threatened the company’s ability to innovate. Satya Nadella’s appointment as CEO marked a decisive shift, with empathy and emotional intelligence at the forefront of his leadership.

EI-Driven Initiatives:

1. Listening Tours & Empathy Forums:

• Nadella began with a corporate-wide listening tour—over eight weeks, he met small groups of employees, asking open-ended questions (“How do you feel the organization treats your ideas?”) and actively reflecting back their concerns. By acknowledging anxiety about mobile strategy and cloud positioning, he built trust and modeled vulnerability.

2. Growth Mindset Reinforcement:

• Inspired by Carol Dweck’s growth-mindset research, Nadella explicitly reframed failures as “learn-it-all” opportunities. In all-hands meetings, he shared personal stories of stumbling, reinforcing that emotional resilience and continuous learning trumped perfection. This narrative shift targeted the emotionally stable locus of “I can grow” rather than “I must be right.”

3. “Hackathon” Series with Emotional Checkpoints:

• Microsoft’s annual 24-hour “Hackathon” became a venue not only for coding sprints but also for EI practices. Teams began and ended hackathons with brief guided mindfulness sessions—two-minute breathing exercises—and mid-hack empathy check-ins where members named their stress levels and asked for support. These small EI rituals reduced burnout, enabling more creative risk-taking.

4. Leadership Coaching & 360° EI Feedback:

• Senior leaders participated in a tailored EI coaching program. They underwent MSCEIT-based assessments and 360° feedback focused on empathy, emotional regulation, and social awareness. Coaches worked with them to recognize situations that triggered defensiveness (e.g., public product critiques) and to develop strategies like “active listening huddle” protocols to de-escalate heated debates.

Outcomes:

• Cultural Shift: Employee satisfaction scores (eNPS) rose from 31 to 56 over two years, underpinned by improvements in “I feel heard” and “I can learn from failure” survey items.

• Innovation Uptick: Hackathon participants doubled “incubator projects” adopted into product pipelines, reflecting lowered fear of judgment.

• Financial Performance: By mid-2019, Microsoft’s market capitalization surpassed $1 trillion, partly fueled by renewed focus on cloud services—an outcome traced to collaborative EI-driven culture.

• Empathy as Core Value: Nadella redefined “empathy” as a company value: every internal and external communication referenced the importance of understanding customer and employee emotions. This emphasis on EI directly influenced product designs—e.g., accessibility features in Windows and Office—that resonated with broader user bases.

Case Study: Medtronic’s Post-Merger Integration

In 2017, Medtronic—one of the world’s largest medical device manufacturers—acquired Covidien in a $42.9 billion deal. Combining two large, research-driven cultures risked emotional disengagement, mistrust, and talent attrition. To navigate the merger successfully, Medtronic launched a targeted Emotional Intelligence integration program.

EI-Driven Interventions:

1. “Empathy Ambassadors” Program:

• Across fifty sites worldwide, Medtronic identified and trained 50 “Empathy Ambassadors”—employees nominated by peers for emotional attunement. These ambassadors conducted listening circles, where acquired Covidien employees voiced anxieties (“Will my job change?” “How do cultures align?”). Ambassadors practiced reflective listening and documented emotional themes—uncertainty about leadership, fear of process redundancy, pride in local innovations.

2. EI Integration Workshops:

• Cross-functional teams of Medtronic and Covidien employees attended two-day EI immersion workshops. Modules included:

• Emotional Mapping Exercises: Participants created shared diagrams showing emotional highs (excitement over new market opportunities) and lows (loss of familiar routines), fostering mutual understanding.

• Conflict Embracement Role-Plays: Simulating scenarios—“Disagreement over preferred R&D processes”—teams employed de-escalation techniques (naming emotions, setting No-Blame agreements) to practice EI-driven conflict resolution.

3. Leadership EI Roundtables:

• Executive leaders held monthly roundtables, each beginning with a one-minute “Emotional Pulse Check” (rating feelings on a scale from 1–5). Leaders then shared personal EI practices—journaling prompts, brief meditations, or coaching encounters—that helped them manage merger-related stress. This modeling normalized vulnerability and anchored EI as a leadership priority.

4. Empathy-Focused Communications:

• All merger announcements and integration updates incorporated empathy statements:

• “We understand this is a time of significant change, and many of you may feel uncertain about the future.”

• Each message concluded with a “Support Link” to confidential counseling, group debriefs, or EI micro-learning materials—ensuring emotional resources accompanied informational updates.

Outcomes:

• Reduced Attrition: Voluntary turnover among Covidien employees dropped from a projected 12% to under 5% in the first year—attributed to improved emotional support and clarity.

• Accelerated Synergies: Cross-company project teams reached collaborative milestones 25% faster, as EI practices accelerated trust-building and knowledge sharing.

• Employee Engagement: Post-merger engagement surveys showed a 20-point increase in “I feel valued and heard,” directly linked to empathy ambassador interventions.

• Long-Term Cultural Integration: Two years post-merger, Medtronic’s blended culture scored in the 90th percentile for “Psychological Safety” compared with industry benchmarks, demonstrating that EI-driven integration fostered a resilient, unified organization.

Executive Summary

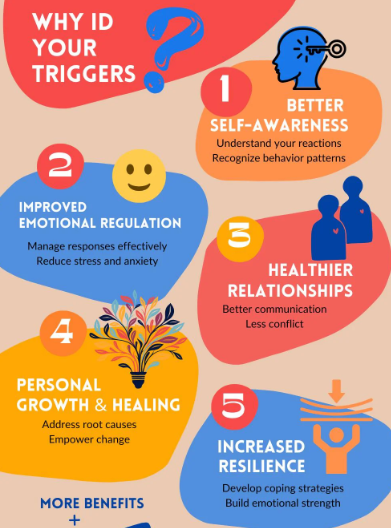

Chapter 1: Emotional Triggers

Periods of change often surface strong emotional responses that, if left unacknowledged, can derail collaboration, decision-making, and progress. Understanding emotional triggers—the specific stimuli that evoke strong reactions—is a foundational step in building emotional resilience during times of transition. These triggers may be rooted in past experiences, personal values, or unmet expectations and can vary widely across individuals and contexts. What feels like a routine process adjustment to one person may provoke anxiety or defensiveness in another due to perceived threats to stability, autonomy, or self-worth.

In the context of organizational change, common emotional triggers include ambiguity around roles, shifts in leadership, new technologies, altered performance expectations, or perceived loss of control. Even well-intended communications can activate underlying fears or insecurities if not carefully framed. Recognizing these triggers early—before emotions intensify—enables more thoughtful responses and helps prevent reactive behaviors that compromise team cohesion.

Developing awareness of emotional triggers requires both introspection and observation. Internally, individuals benefit from cultivating the habit of emotional self-checks—brief moments to pause and notice physiological cues such as tension, irritation, or withdrawal. Journaling or mental reflection after emotionally charged encounters can also reveal recurring patterns and deepen understanding of personal sensitivities. Externally, the ability to detect subtle shifts in tone, body language, or engagement levels among others is key to identifying when a trigger may have occurred.

Learning to recognize triggers is not about eliminating emotional responses, but about understanding the context in which they arise and responding with greater composure. With practice, individuals can distinguish between the stimulus and the story they attach to it—reframing a terse message from a colleague as time pressure rather than hostility, for example. Teams that adopt shared language around triggers—such as “I’m noticing I feel triggered when expectations aren’t clear”—create a psychologically safe space for emotional transparency and constructive dialogue.

By understanding and managing emotional triggers, organizations can foster a more emotionally intelligent workforce. This capacity reduces the likelihood of conflict escalation, supports more empathetic communication, and enhances overall adaptability during change. It also empowers individuals to take responsibility for their own emotional states while respecting the reactions of others, promoting trust and cohesion even in uncertain environments. Over time, identifying and defusing emotional triggers becomes a critical component of sustained change resilience.

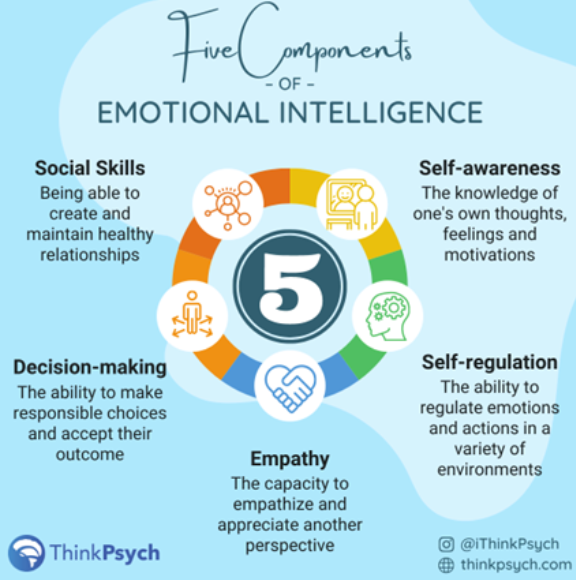

Chapter 2: The Five Components of Emotional Intelligence

Navigating change effectively requires more than technical proficiency or strategic vision; it demands a deep understanding of emotional dynamics. Daniel Goleman’s five domains of emotional intelligence—self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills—offer a comprehensive framework for leading with composure, clarity, and connection in times of transition. These components, when developed and practiced, equip individuals and teams to manage uncertainty, foster collaboration, and sustain momentum through the most complex transformation efforts.

Self-awareness forms the cornerstone of emotional intelligence. It involves the ability to recognize one’s own emotions, identify their sources, and understand how those emotions influence behavior and decision-making. In a change environment, self-awareness allows individuals to notice their reactions to stressors such as shifting responsibilities or ambiguous expectations and adjust their responses accordingly. Tools such as reflective journaling, emotional check-ins, and mindfulness practices can enhance this internal clarity.

Self-regulation builds upon self-awareness by providing the skills to manage disruptive emotions and impulses. Rather than reacting defensively or withdrawing under pressure, emotionally intelligent individuals pause, reflect, and respond with intention. Strategies such as breathing techniques, reframing thoughts, or seeking perspective allow for more constructive engagement even when emotions run high. This discipline promotes steadiness in leadership and fosters a climate of psychological safety within teams.

Motivation, in the context of emotional intelligence, extends beyond external rewards. It reflects an internal drive to pursue goals with energy, resilience, and a learning mindset. Change often introduces setbacks, uncertainty, and ambiguity. Emotionally intelligent individuals maintain motivation by focusing on purpose, aligning with long-term values, and interpreting obstacles as opportunities for growth rather than threats to competence.

Empathy enables individuals to perceive and understand the emotions of others. It involves attentive listening, interpreting non-verbal cues, and appreciating the diverse emotional responses that change can provoke. Empathy fosters stronger relationships and reduces the likelihood of misunderstanding or disengagement, particularly when team members are navigating personal uncertainty or professional disruption.

Social skills translate emotional understanding into action. This domain includes the ability to manage relationships, influence others constructively, navigate conflict, and foster collaboration. In a changing environment, strong social skills allow leaders and colleagues to build trust, maintain open lines of communication, and coordinate efforts with flexibility and respect.

Together, these five domains provide a practical and powerful model for building emotional intelligence in the context of organizational change. Cultivating these competencies not only improves individual adaptability but also strengthens team resilience and accelerates cultural alignment. By embedding these principles into everyday leadership behaviors, organizations can transform emotional awareness into a strategic asset—one that enhances performance, deepens trust, and sustains change readiness over the long term.

Chapter 3: Emotional Hijacking and Recovery

High-stress environments, especially those marked by rapid change, often trigger strong emotional responses that can override logical thinking and derail productive behavior. This phenomenon, commonly referred to as emotional hijacking, occurs when the brain’s emotional center—the amygdala—responds to perceived threats with a surge of reactivity, bypassing the more rational and measured functions of the prefrontal cortex. In these moments, individuals may lash out, withdraw, or make impulsive decisions that compromise collaboration, communication, and trust.

Understanding the science behind emotional hijacking is essential to mitigating its impact. When individuals feel overwhelmed, disrespected, or threatened—whether by shifting responsibilities, ambiguous expectations, or interpersonal friction—the emotional brain reacts automatically. This fight, flight, or freeze response, while evolutionarily designed for survival, often proves counterproductive in modern organizational settings. Recognizing the early warning signs of hijacking—such as increased heart rate, shallow breathing, or sudden frustration—enables individuals to interrupt the emotional cascade before it takes hold.

Recovery from emotional hijacking requires both awareness and practical intervention strategies. Mindfulness-based techniques, such as focused breathing or grounding exercises, help reset the nervous system and restore cognitive balance. Pausing to reflect, stepping away briefly, or engaging in mental reframing—such as shifting from “this is a threat” to “this is a challenge I can handle”—can transform reactive energy into calm, intentional action.

Structured recovery protocols support more consistent application of these strategies. For example, individuals might adopt a personal mantra or anchor phrase that reinforces composure, such as “Respond, don’t react.” Scheduled reflection time at the end of each day or after high-stakes meetings can also provide insight into recurring emotional triggers and help fine-tune self-regulation techniques over time. Additionally, peer support systems—where trusted colleagues offer perspective or serve as sounding boards—reinforce recovery and model emotionally intelligent behavior across teams.

In group settings, organizations can support recovery from emotional hijacking by fostering a culture of psychological safety. Creating space to acknowledge emotional reactions without judgment—through team debriefs, restorative conversations, or emotional check-ins—normalizes the experience and reduces shame or defensiveness. Leaders who openly share their own emotional recovery strategies set a tone of transparency and resilience, encouraging others to do the same.

Ultimately, learning to navigate emotional hijacking transforms reactive patterns into responsive strength. Individuals and teams become better equipped to handle pressure, recover from setbacks, and re-engage with clarity and purpose. By embedding these recovery strategies into everyday practices, organizations enhance their capacity for resilience, enabling more thoughtful decision-making and sustainable performance in the face of ongoing change.

Chapter 4: Empathy in Action

Empathy plays a pivotal role in maintaining trust, connection, and cohesion during times of organizational change. It enables individuals to move beyond surface-level interactions and respond meaningfully to the emotional undercurrents that often shape how change is received. When people feel heard, understood, and supported, their openness to uncertainty increases, and resistance often gives way to collaboration and shared purpose.

Empathy in action begins with the ability to recognize emotional cues—both verbal and non-verbal. These may include changes in tone, facial expressions, body language, or patterns of communication such as withdrawal or agitation. In virtual environments, cues may be subtler, such as delayed responses or reduced participation. Attentive observation combined with curiosity helps individuals detect when colleagues may be experiencing anxiety, frustration, or confusion, even if those feelings are not explicitly stated.

Once emotional cues are identified, the next step is to interpret them accurately. This requires stepping into the other person’s perspective, considering their context, and resisting the urge to minimize or explain away their emotional state. Effective interpretation means acknowledging that different individuals experience change differently—what inspires excitement for one may provoke fear or uncertainty in another. Empathy enables individuals to withhold judgment, create space for expression, and offer validation that fosters psychological safety.

Responding empathetically involves both listening and engaging. Active listening practices—such as paraphrasing, asking clarifying questions, and using open body language—signal genuine interest and respect. Empathetic responses might include naming the observed emotion (“It sounds like you’re feeling overwhelmed”) and following up with a supportive gesture or practical offer of help. These moments of connection humanize the change process, strengthen relationships, and lay the groundwork for trust-based collaboration.

In the broader organizational context, embedding empathy into change practices means designing communications, policies, and processes with emotional impact in mind. Transparent messaging that acknowledges potential discomfort, provides reassurance, and invites feedback demonstrates emotional attunement. Leadership behaviors that prioritize listening, openness, and responsiveness further model the value of empathy at every level of the organization.

When empathy becomes an embedded norm, teams function with greater alignment and less friction. Misunderstandings are reduced, conflicts are addressed early, and diverse perspectives are welcomed as assets rather than threats. Empathy also supports resilience by ensuring that individuals feel supported even when challenges arise—building a sense of shared experience and collective strength.

Cultivating empathy during change is not a soft skill reserved for specific roles; it is a strategic capability that transforms the emotional climate of organizations. By recognizing, interpreting, and responding to emotional cues with care and intention, individuals contribute to a culture of connection that enables smoother transitions, more inclusive dialogue, and stronger long-term outcomes.

Chapter 5: Emotional Tone in Communication

In the midst of organizational change, communication takes on heightened importance—not just in terms of content, but also in how messages are delivered. The emotional tone of communication, shaped by facial expressions, vocal intonation, body language, and other non-verbal cues, can either foster psychological safety or introduce subtle barriers to trust and engagement. Even when the words themselves are neutral or positive, mismatched tone or non-verbal signals can unintentionally convey disapproval, indifference, or tension.

Understanding emotional tone begins with recognizing that every interaction communicates more than just information. The way something is said—whether it is rushed or measured, warm or distant, open or guarded—can deeply influence how it is received. During times of uncertainty or transition, recipients are often more emotionally sensitive, making them particularly attuned to tone. A supportive message delivered with impatience or dismissiveness can erode morale, while a difficult message conveyed with empathy and openness can strengthen trust.

Facial expressions serve as one of the most immediate and visible indicators of emotional tone. A furrowed brow, forced smile, or lack of eye contact may signal tension or disinterest, even in otherwise positive discussions. In digital settings, the absence of visible cues can amplify ambiguity, making vocal tone and phrasing even more critical. A flat tone or abrupt phrasing may be interpreted as disapproval or stress, while a calm, measured voice communicates thoughtfulness and stability.

Body language also plays a key role. Posture, gestures, and physical positioning—such as crossing arms, leaning away, or avoiding engagement—can shape the emotional climate of a conversation. Leaders and team members who are mindful of their physical presence often create a sense of approachability and openness that encourages candid dialogue and emotional expression.

Effective communication during change involves aligning verbal messages with non-verbal tone. This alignment fosters psychological safety, the sense that it is safe to speak up, take risks, or admit uncertainty without fear of ridicule or reprisal. Psychological safety, in turn, supports collaboration, innovation, and emotional resilience—critical ingredients for navigating complex transitions.

Developing emotional tone awareness requires both self-monitoring and feedback. Individuals benefit from reflecting on how their tone is perceived and seeking input from trusted colleagues. Simple practices, such as slowing speech when delivering difficult news, making deliberate eye contact in virtual meetings, or pausing to check for emotional reactions, can have a powerful impact on how messages are received.

By cultivating greater sensitivity to tone and non-verbal cues, organizations can ensure that communication serves as a bridge rather than a barrier. Emotionally attuned communication not only improves clarity and understanding but also reinforces a culture of respect, trust, and shared purpose—particularly vital in times of change.

Chapter 6: Cultivating Self-Awareness in Real Time

In the context of organizational change, emotional self-awareness becomes a critical tool for managing stress, maintaining composure, and making informed decisions. While long-term reflection has value, the ability to recognize emotions as they arise—real-time self-awareness—offers a more immediate advantage. It allows individuals to pause, assess, and choose their responses rather than being carried away by impulse or reactivity. Developing this skill requires deliberate practice, supported by structured tools and consistent habits.

Real-time self-awareness begins with the simple act of noticing. Individuals who can identify their emotional states in the moment—whether it’s rising frustration during a tense meeting or a sudden wave of anxiety before a new task—gain the capacity to intervene constructively. This awareness serves as a mental “signal,” alerting the individual to potential stress responses before they escalate or influence behavior unconsciously.

Practical tools such as emotion journaling help individuals track their emotional patterns throughout the day. By recording key moments—what triggered an emotion, how it manifested, and what response followed—individuals start to see connections between specific situations and emotional reactions. Over time, this pattern recognition strengthens anticipatory awareness, allowing for earlier and more proactive emotional management.

Reflective pauses are another vital practice. These intentional moments of stillness—such as taking a deep breath before responding to feedback or briefly stepping away after a challenging conversation—create a gap between stimulus and response. Even a few seconds of conscious reflection can disrupt automatic emotional reactions and open the door to more thoughtful, values-aligned choices.

Other real-time techniques include body scanning (noticing physical signs of stress like muscle tension or shallow breathing), using emotional labeling (“I feel irritated”), and anchoring statements (“This is a moment of growth”). Together, these practices turn attention inward without judgment, helping individuals stay grounded and responsive during periods of heightened pressure or ambiguity.

Building self-awareness in real time also benefits from environmental cues and team rituals. For instance, organizations can normalize quick emotional check-ins at the start of meetings, prompting individuals to assess their current state. Visual cues like desk prompts or brief mindfulness reminders can support the habit of tuning in before reacting.

Ultimately, cultivating self-awareness as emotions unfold enhances emotional intelligence and resilience. It empowers individuals to regulate their behavior more effectively, strengthen interpersonal dynamics, and remain centered amid rapid change. In teams and organizations, this level of awareness supports clearer communication, more productive conflict resolution, and a stronger foundation for trust and psychological safety.

By making real-time emotional insight part of the daily rhythm, individuals and groups become more agile, composed, and aligned—qualities essential for thriving in a constantly evolving work environment.

Chapter 7: Regulating Emotions Under Pressure

Maintaining emotional balance during high-pressure moments is a defining feature of resilience, particularly in environments undergoing change. As stress mounts and uncertainty increases, the ability to regulate emotional responses becomes crucial—not only for individual well-being but also for preserving team cohesion, decision quality, and overall performance. Emotional regulation does not imply suppressing emotions, but rather managing them in ways that allow for clarity, composure, and constructive action.

Effective regulation begins with recognizing the onset of emotional intensity—frustration, anxiety, defensiveness, or overwhelm—and engaging techniques that bring the nervous system back into equilibrium. One of the most widely practiced approaches is cognitive reframing: the deliberate act of interpreting a situation from a different, more constructive perspective. For instance, rather than viewing a difficult project revision as a failure, reframing it as a learning opportunity or a refinement phase can reduce emotional distress and renew motivation.

Mindfulness techniques further support emotional regulation by grounding attention in the present moment. These practices might include focused breathing, brief meditative pauses, or guided body scans. Even short mindfulness breaks help reduce cortisol levels, restore mental clarity, and interrupt the physiological stress response triggered by high-stakes or emotionally charged situations. When integrated into daily routines, these techniques increase tolerance for discomfort and enhance one’s ability to navigate ambiguity with greater calm.

Breathing strategies, particularly diaphragmatic or box breathing, provide an immediate and accessible way to down-regulate emotional arousal. These techniques activate the body’s relaxation response, slow the heart rate, and reduce physical symptoms of stress. Taking a few intentional breaths before delivering feedback, responding to criticism, or entering a tense meeting can help preserve composure and create space for thoughtful engagement.

Emotion regulation is also strengthened by reflective habits. Journaling after emotionally intense moments allows individuals to unpack their reactions, explore what triggered them, and identify more effective coping strategies for the future. Over time, these reflections build emotional insight and increase confidence in managing difficult situations.

In a team setting, modeling emotional regulation sets a powerful tone. Leaders who remain centered during crises, acknowledge their feelings without projecting them, and demonstrate thoughtful responses serve as emotional anchors for others. Organizations that normalize the use of regulation tools—such as short group mindfulness exercises or structured pauses during meetings—reinforce a culture of composure and thoughtful action.

By mastering emotional regulation techniques, individuals enhance their ability to respond with intention rather than react impulsively. This discipline supports more respectful communication, better decision-making, and stronger collaboration. In environments of change, where stress is unavoidable, regulated emotions create the stability needed to navigate challenges with resilience and resolve.

Chapter 8: Emotional Contagion in the Workplace

In any workplace setting, emotions are not contained within individuals—they ripple across teams, shaping the overall climate in both subtle and profound ways. This phenomenon, known as emotional contagion, refers to the transfer of emotional states from one person to another, often unconsciously. During periods of change or uncertainty, this dynamic becomes especially influential, as heightened sensitivity to mood and tone can amplify either resilience or unrest within the organization.

Emotional contagion occurs through verbal and non-verbal cues such as tone of voice, facial expressions, posture, and word choice. A single moment of visible frustration from a team leader can dampen morale across a department, just as genuine expressions of optimism or calm can instill confidence and energy. These emotional cues are quickly interpreted, mirrored, and absorbed, making mood contagious—especially in close-knit or highly collaborative teams.

Leaders and influential team members play a central role in setting the emotional tone. Their behavior often acts as a reference point for others, particularly during times of uncertainty. Leaders who demonstrate steadiness, openness, and empathy help stabilize the emotional environment. By contrast, expressions of panic, defensiveness, or blame can foster anxiety, mistrust, or disengagement that spreads rapidly and undermines collective focus.

Intentional emotional leadership involves both self-awareness and active regulation. Leaders who recognize their own emotional states and manage them thoughtfully prevent unintentional transmission of stress or negativity. In parallel, they can consciously model emotional resilience—offering reassurance, maintaining perspective, and acknowledging challenges without dramatization. These behaviors encourage a constructive emotional climate where others feel supported, even when navigating difficult transitions.

Team rituals and communication practices can also shape emotional contagion. Starting meetings with emotional check-ins, highlighting positive developments, or pausing to recognize collective effort contributes to a more grounded and hopeful atmosphere. Celebrating small wins, expressing gratitude, and normalizing discussion around emotional responses to change help create a culture where feelings are acknowledged but not allowed to derail progress.

Digital environments present unique challenges and opportunities for managing emotional contagion. The absence of physical cues can make misinterpretation more likely, so tone and clarity in written communications are especially important. Emojis, punctuation, and brief emotional signposts (“This is a challenging change, but I’m confident in our ability to adapt”) can help convey empathy and optimism. Virtual leadership requires deliberate efforts to maintain visible positivity and emotional steadiness.