Navigating Projects – Workshop 5 (Finance Management)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Navigating Projects is provided by Mr. Williams Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Mr Williams has extensive experience in designing, developing, and successfully delivering portfolios, programs, and projects for various entities, both government and enterprise, across the globe. He has worked with organizations in Australia, Asia, the United Kingdom, Europe, New Zealand, and Fiji.

Recently, he has been leveraging his expertise for numerous organizations to craft portfolio, program, and project frameworks along with attendant processes and procedures. This includes designing and implementing the establishment of portfolio management offices for international enterprises and government organizations. On their behalf, he has also delivered facilitated training workshops and one-on-one mentoring to support them, ensuring they are well-equipped for success.

During his career, Mr Williams has held various roles managing and delivering a wide range of strategic programs and projects, transformation programs, rollouts, integrations, upgrades, and migrations, both ICT and Business focused, for the public and private sectors. He is also an expert in process and procedure usage and is often called upon to provide gateway assurance, and organizational maturity uplifts to government departments and international organizations. He has vast experience in business transformation, strategy and scaling, including designing, developing, and implementing end-to-end business change processes and controls to support portfolios, programs, and projects.

Some of his recent personal achievements include developing a specialist ICT Portfolio Management Framework, the first of its kind for the Queensland State Government. Furthermore, he led the development and implementation of an IT PMO practice for an international enterprise based in Sydney. His efforts resulted in the successful establishment of a comprehensive IT PMO practice, complete with a clear vision, strategy, and roadmap for success.

His service skills include portfolio, program, and project management delivery process improvement and performance; process development and testing; business maturity consulting; planning, developing and establishing PMOs; team management and leadership; business case development; management of risk; strategic discovery and planning; ICT, Cloud and On-premises Solutions Management and Delivery

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

Part 1 Month 5 Finance Management – Finance is an essential resource that must be a key focus for initiating and controlling initiatives. This module demonstrates how to capture and evaluate the likely costs of an initiative within a formal business case and how to categorize and manage costs throughout the investment lifecycle. It will also demonstrate methods of developing formal funding requests for new and existing initiatives. Delegates will gain an understanding of the finance management process, including how it ensures the availability and scheduling of funds to support investment decisions. However, this module’s focus is not just on finance but takes the delegate through developing a business case. Delegates will discover how a well written business case is used to provide the evaluated costs of the initiative, define its value to the business and contain a financial appraisal of the possible options. Delegates will discover how to ensure the business case is at the core of decision making during the initiative’s lifecycle. Also, it shows how to use the business case to provide the problem statement and details of the analysis of cost to benefit associated with alternative actions and options that led to the preferred solution.

Objectives

01. Strategic Finance Management in Change Initiatives: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Fundamentals of Cost Estimation and Budget Planning: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Funding Models and Investment Approval Processes: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Developing a Compelling Business Case: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Financial Appraisal and Cost-Benefit Analysis: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Integrating Risk, Contingency and Financial Controls: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Lifecycle-Based Financial Monitoring and Control: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Business Case as a Living Document: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Stakeholder Engagement and Financial Transparency: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Lessons Learned and Best Practice in Finance and Case Development: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Strategic Finance Management in Change Initiatives: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Fundamentals of Cost Estimation and Budget Planning: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Funding Models and Investment Approval Processes: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Developing a Compelling Business Case: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Financial Appraisal and Cost-Benefit Analysis: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Integrating Risk, Contingency and Financial Controls: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Lifecycle-Based Financial Monitoring and Control: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Business Case as a Living Document: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Stakeholder Engagement and Financial Transparency: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Lessons Learned and Best Practice in Finance and Case Development: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Strategic Finance Management in Change Initiatives.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Fundamentals of Cost Estimation and Budget Planning.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Funding Models and Investment Approval Processes.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Developing a Compelling Business Case.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Financial Appraisal and Cost-Benefit Analysis.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Integrating Risk, Contingency and Financial Controls.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Lifecycle-Based Financial Monitoring and Control.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Business Case as a Living Document.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Stakeholder Engagement and Financial Transparency.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Lessons Learned and Best Practice in Finance and Case Development.

Introduction

Finance management sits at the heart of effective program and project delivery. It is both a foundational enabler and a critical control mechanism, ensuring that initiatives are not only well-conceived but also sustainably executed. Without a disciplined approach to financial oversight, even the most innovative or strategically aligned projects can falter. The capacity to initiate and control initiatives depends as much on sound financial planning as it does on technical expertise or operational efficiency.

Finance is more than a record of expenditures—it is the backbone of informed decision-making. By capturing, evaluating, and controlling costs, finance management allows organizations to assess whether a given initiative represents a worthwhile investment of resources. It helps set the boundaries for what is achievable, provides clarity on trade-offs, and ensures that objectives remain financially viable throughout the lifecycle of an initiative.

Central to this discipline is the business case, which serves as both a proposal and a guiding document. A well-developed business case synthesizes financial, operational, and strategic considerations, enabling leadership to make evidence-based investment decisions. From initial cost projections to ongoing benefit evaluations, the business case operates as a living framework that keeps financial priorities aligned with organizational goals.

This module explores how finance management operates across the entire investment lifecycle—from early-stage estimation and categorization of costs, through to funding requests, cost control, and benefit realization. It examines not only the mechanics of financial appraisal but also the strategic role finance plays in ensuring initiatives remain on course and deliver value.

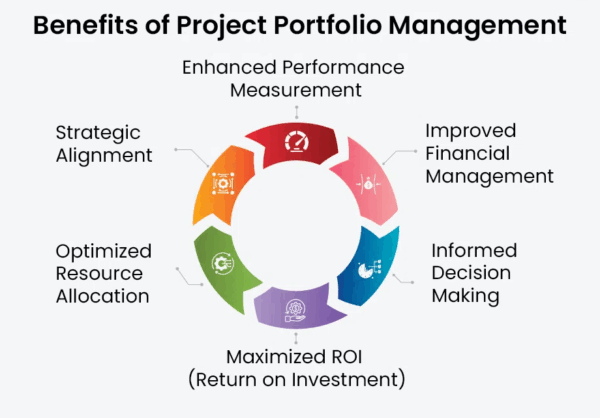

The Strategic Importance of Finance in Initiatives

The relationship between finance and successful initiatives is deeply interwoven. Finance functions not merely as a support service but as a central strategic lever—determining which initiatives move forward, at what scale, and with what expectations for return. In both public and private sector organizations, finance serves as the mechanism through which finite resources are allocated to activities believed to deliver the greatest value. That value may be expressed in terms of profitability, efficiency, competitive positioning, social impact, or long-term resilience, but in every case, finance plays the critical role of enabling, shaping, and constraining the possibilities.

In complex operating environments where demands exceed available resources, finance management becomes a strategic filter—a means of distinguishing between promising ideas and initiatives that are either unviable or poorly aligned with organizational objectives. It does so by bringing structure to decision-making, ensuring that investment choices are grounded in empirical evaluation rather than intuition or optimism. A robust finance framework challenges assumptions, quantifies trade-offs, and ensures that funding is directed toward initiatives most likely to contribute measurable value.

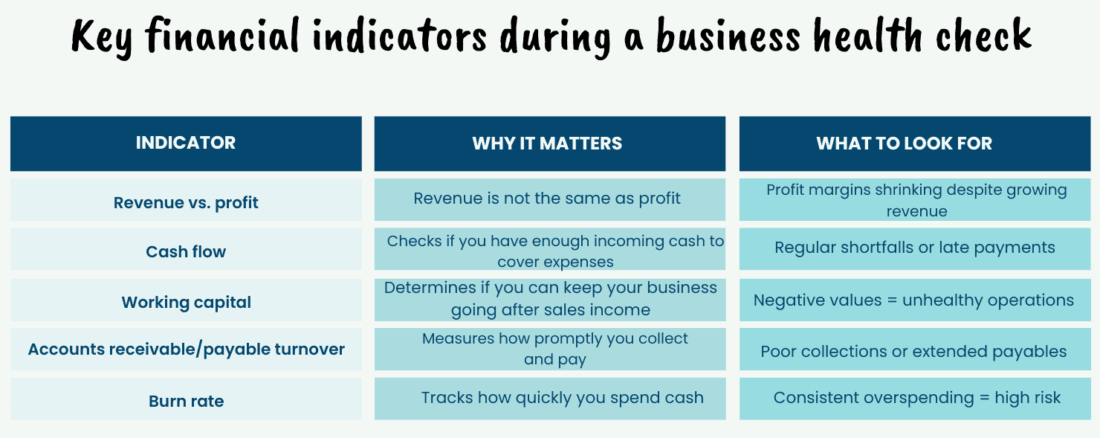

This evaluative function is particularly important in portfolio environments, where multiple programs and projects are simultaneously under consideration. Finance management helps resolve competing claims on capital by facilitating comparison between initiatives using standard financial metrics such as net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), payback period, or cost-benefit ratios. These tools enable decision-makers to weigh the relative merits of each initiative not only based on projected financial return but also on strategic alignment, timing, risk exposure, and dependency on other initiatives.

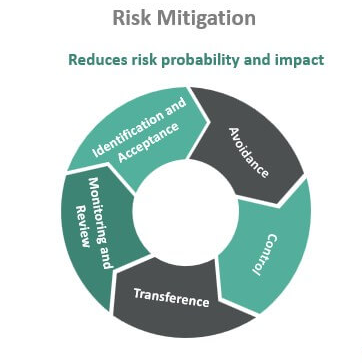

Moreover, the role of finance is not confined to upfront assessments. As initiatives transition from planning into execution, finance management provides ongoing control and visibility, allowing organizations to respond dynamically to changes in scope, cost, or environmental conditions. This ongoing involvement supports risk mitigation by enabling early intervention when deviations occur. It ensures that changes in cost estimates, resourcing needs, or delivery timelines are evaluated in financial terms, so that corrective actions can be taken without undermining strategic goals.

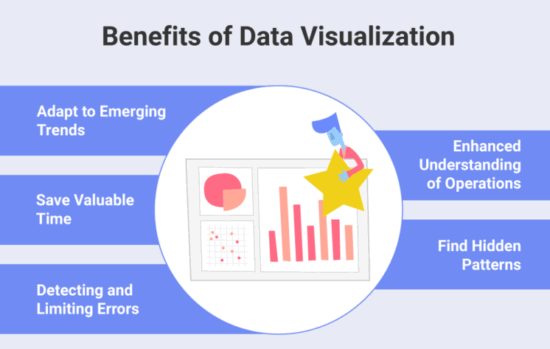

This control function is made possible through processes such as cost tracking, variance analysis, and forecasting, all of which ensure that expenditures remain within acceptable boundaries. The ability to monitor financial performance in real time—and to course-correct when necessary—helps prevent resource drain and protects the value proposition articulated in the original business case.

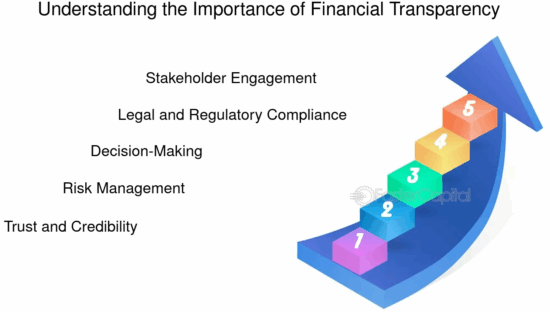

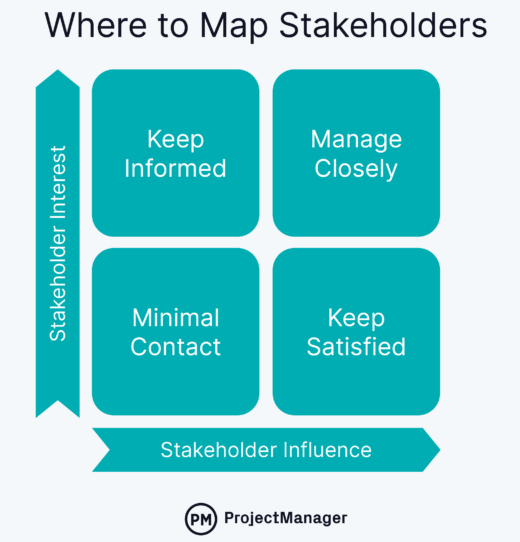

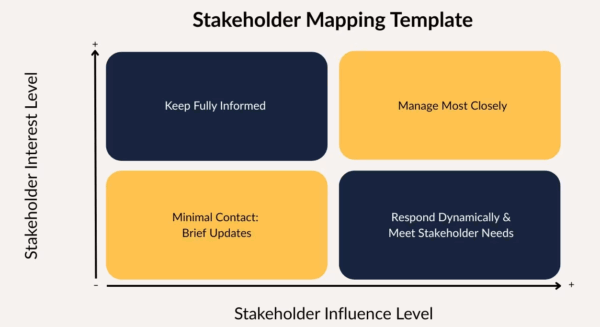

In addition to enabling decision-making and maintaining control, finance serves as a key driver of governance and accountability. Transparency in financial management is essential for maintaining stakeholder confidence. When organizations manage large or high-risk initiatives—especially those involving public funds, partnerships, or regulatory oversight—the demand for financial clarity intensifies. Stakeholders expect to see where and how resources are being used, what value is being delivered in return, and how financial risks are being addressed.

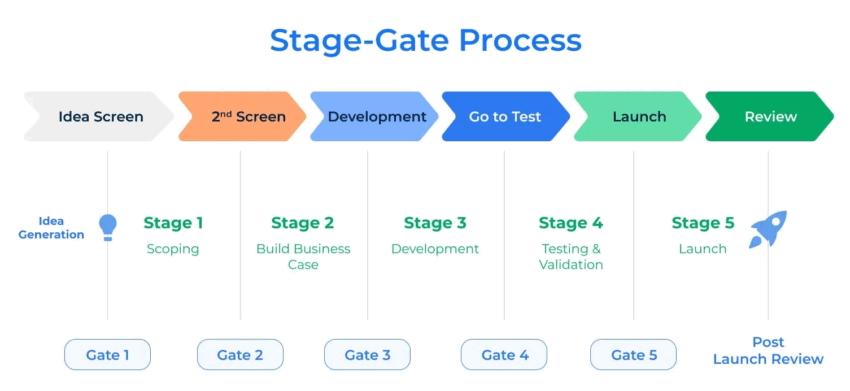

This expectation has led to the rise of structured financial governance mechanisms such as stage-gated funding, milestone-linked approvals, and post-investment reviews. These tools ensure that initiatives remain justifiable at every stage of their lifecycle and provide a defensible audit trail in support of governance requirements. Finance management, in this sense, becomes a pillar of organizational integrity, reinforcing disciplined delivery and maintaining alignment between promises made and outcomes delivered.

Another often overlooked dimension of finance in strategic initiatives is its role in communication. Financial data serves as a shared language among diverse stakeholders—including executives, delivery teams, investors, and regulators—each of whom may have different perspectives on success. By converting strategic goals and delivery plans into quantifiable terms, finance creates a common framework for discussion, negotiation, and decision-making. This is particularly valuable in cross-functional initiatives where different priorities must be reconciled.

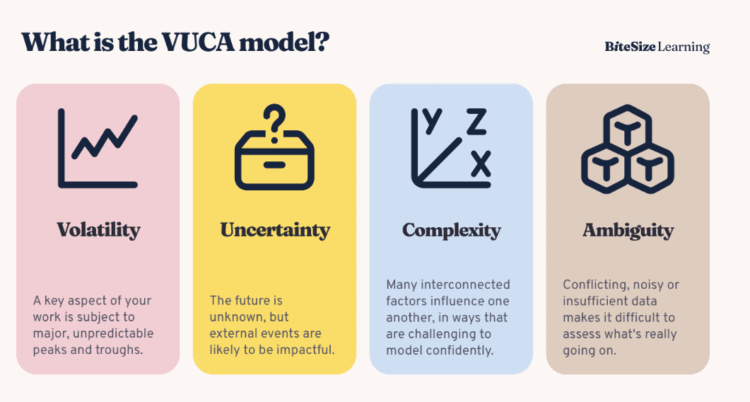

Finance also supports adaptive decision-making. In today’s volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) business environment, organizations must be ready to pivot. Finance management enables this by continuously updating cost and benefit forecasts, allowing decision-makers to reevaluate initiatives as new data becomes available. If an initiative is no longer viable or less strategically relevant than anticipated, finance provides the data needed to make difficult decisions—whether to re-scope, pause, or terminate a project—in an informed and timely manner.

Ultimately, the strategic importance of finance in initiatives lies in its ability to serve multiple roles simultaneously: enabler, evaluator, controller, communicator, and guardian of value. It is through finance that ideas are tested, refined, approved, and resourced. It is through finance that progress is monitored and guided. And it is through finance that accountability is maintained and value is ultimately realized. Without strong finance management, even the most ambitious or visionary initiative risks veering off course, overshooting its budget, or failing to deliver meaningful outcomes. With it, initiatives gain not only funding but direction, discipline, and legitimacy.

The Investment Lifecycle and Cost Evaluation

Every initiative unfolds across a structured investment lifecycle, each stage carrying distinct financial responsibilities, risks, and evaluation criteria. The ability to manage finance across this continuum—from conceptualization through benefit realization—is fundamental to organizational control, accountability, and the consistent delivery of value. Finance management is not confined to the budgeting of isolated tasks; it is an ongoing, dynamic process that enables strategic decision-making at every point along the initiative’s trajectory.

Understanding the investment lifecycle is essential for aligning financial resources with operational needs. It ensures that funding is not only sufficient but also available when required, and that it is deployed in a way that maximizes return, minimizes waste, and supports the initiative’s evolving objectives. Misalignment at any stage—whether through underestimation of early costs or failure to monitor expenditures in real time—can compromise delivery and erode confidence in the initiative’s viability.

Initiation Phase: Establishing Financial Feasibility

The financial journey begins with the initiation phase, where the organization must decide whether to allocate resources to further develop a concept. At this stage, financial inputs are typically limited to high-level cost approximations, drawn from benchmarking data, historical projects, or expert judgment. These early estimates serve two core purposes: to establish a rough order of magnitude for the investment required and to determine whether the concept is worth pursuing.

Because data is limited, these estimates are inherently uncertain. Nonetheless, they must be sufficiently robust to support preliminary go/no-go decisions. The goal is not to produce detailed forecasts but to offer a credible starting point for financial planning. Initial estimates also feed into early versions of the business case, providing stakeholders with a financial frame of reference for evaluating strategic relevance and potential return.

Flexibility is critical during this phase. Assumptions are tested and revised as more information becomes available. Finance management must support agility, allowing for the refinement of cost projections without undermining the initiative’s momentum.

Planning Phase: Refining Cost Estimates and Defining Financial Structure

Following concept validation, initiatives enter the planning phase, where detailed cost evaluation becomes a central focus. At this stage, financial models are built around specific scopes of work, procurement strategies, timelines, and resource requirements. Costs are broken down into individual components such as materials, labor, licensing, logistics, overheads, and contingency reserves.

Multiple cost scenarios are often developed to reflect different design choices, delivery models, or risk tolerances. This enables decision-makers to compare the financial implications of alternative paths and to balance ambition with affordability. For example, one version of the plan may prioritize speed to market at a higher cost, while another emphasizes long-term cost efficiency with a slower implementation timeline.

Financial structuring also takes place during this phase. This includes defining how costs will be phased across time, how they align with funding availability, and whether external financing or partnerships will be required. Detailed cost breakdowns support funding requests and provide the basis for formal budget approval.

This phase represents the foundation of financial accountability. The forecasts produced here form the baseline against which all future performance is measured. Precision and clarity are essential, not only for internal governance but also for building trust among external stakeholders, sponsors, or regulators.

Execution Phase: Monitoring and Managing Expenditures

During the execution phase, finance management shifts from projection to real-time monitoring and control. This is the point at which financial discipline is tested, as actual expenditures begin to replace forecasts, and unforeseen costs emerge.

Key financial processes in this phase include:

• Cost tracking: Recording actual spend against budgeted items in a consistent and timely manner.

• Variance analysis: Identifying differences between planned and actual costs, understanding root causes, and assessing their impact on overall performance.

• Forecast updating: Revising remaining cost estimates based on current performance and emerging risks.

This phase requires close coordination between finance professionals and initiative managers. While project leaders may focus on operational deliverables, finance teams provide the analytical insight needed to ensure that those deliverables are being achieved within the approved financial envelope.

Effective finance management in this phase helps maintain alignment between spending and value delivery. It also supports informed decision-making around potential scope changes, allowing leaders to understand the financial implications of adaptations before committing to them.

Financial reporting is another key element. Timely, accurate reporting supports transparency and enables governance bodies to take proactive action if the initiative deviates from its approved financial path.

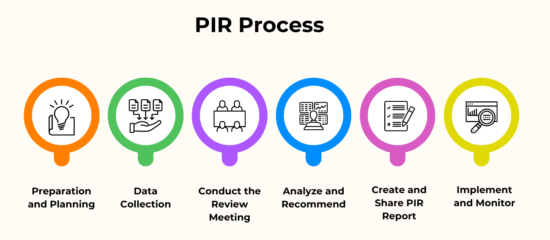

Closure and Post-Investment Review: Evaluating Return and Capturing Lessons

Once the initiative reaches completion, finance management enters the closure and post-investment review phase. This phase is sometimes undervalued, but it plays a vital role in validating whether the anticipated return on investment has been realized—and in identifying lessons to strengthen future initiatives.

Post-investment review involves comparing actual costs and benefits to those forecasted in the original business case. Discrepancies are analyzed to understand whether they resulted from flawed assumptions, execution challenges, or external changes. This analysis can reveal strengths in financial planning as well as areas for improvement.

This phase also involves evaluating long-term benefits. Some outcomes may not be immediately measurable upon completion, particularly in initiatives focused on transformation, capability building, or social value. Finance teams may develop benefit tracking frameworks that extend beyond the initiative’s formal end date, ensuring that intended value is captured and that corrective actions can be taken if it falls short.

The insights generated during this phase contribute to organizational learning. They inform future cost estimations, risk assessments, and funding strategies, making finance management a contributor to continuous improvement.

Financial Appraisal Techniques: Supporting Sound Decision-Making

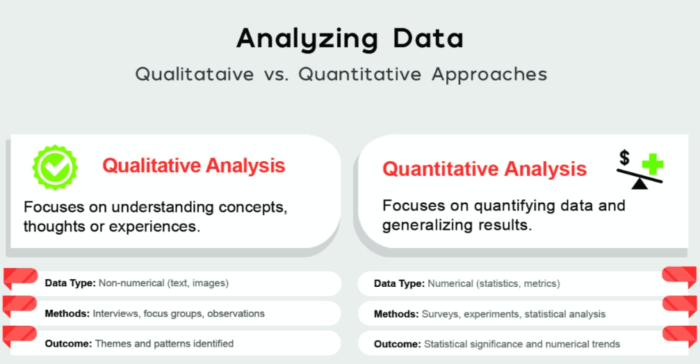

At every stage of the investment lifecycle, financial decision-making is guided by cost evaluation techniques. These techniques provide structured methods for assessing the economic viability of an initiative and comparing alternative investment options.

Common methods include:

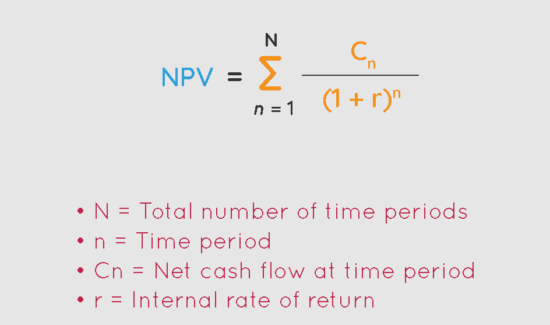

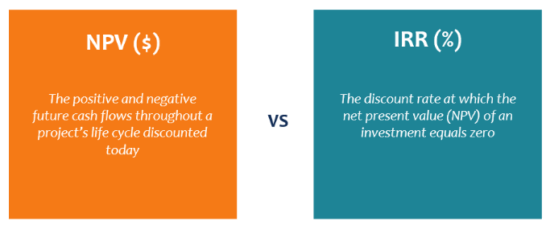

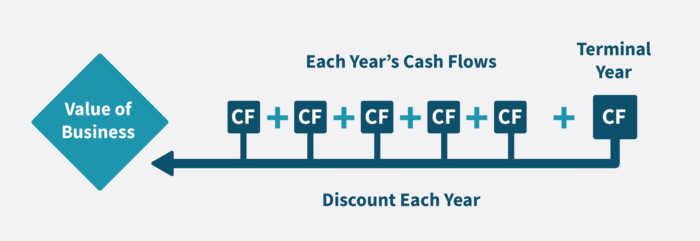

• Net Present Value (NPV): Calculates the present value of future cash flows, adjusted for time and discount rate, to determine whether an initiative will create net value.

• Internal Rate of Return (IRR): Estimates the discount rate at which the present value of costs equals the present value of benefits, indicating expected profitability.

• Payback Period: Measures how long it will take to recoup the initial investment, offering a simple view of financial risk exposure.

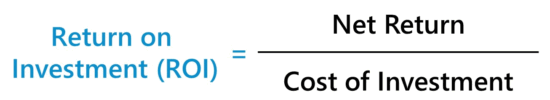

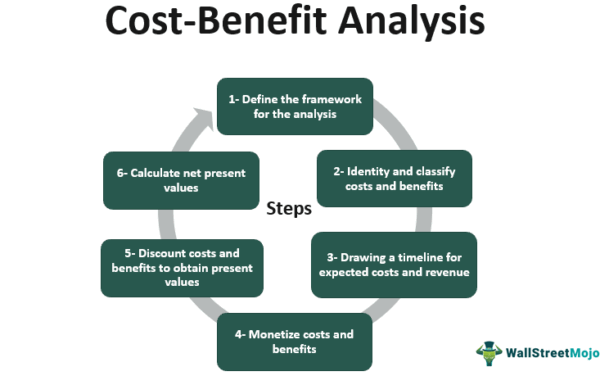

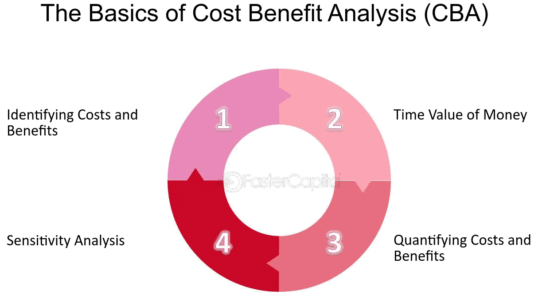

• Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA): Weighs the total expected benefits against the total expected costs, often incorporating qualitative considerations.

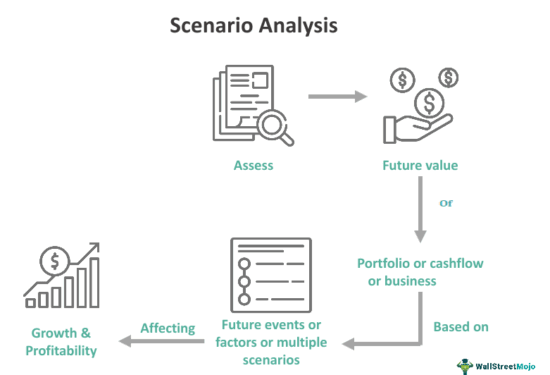

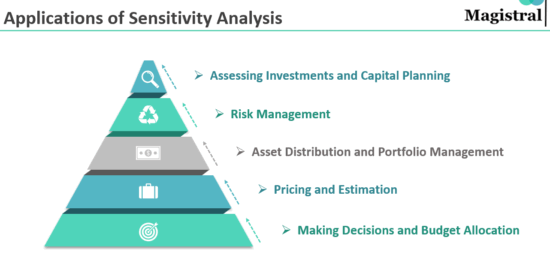

• Sensitivity and Scenario Analysis: Tests how results change under different assumptions or external conditions, improving resilience in decision-making.

These methods offer more than mathematical outputs—they shape how initiatives are discussed, approved, and governed. They also encourage transparency and objectivity, particularly when multiple stakeholders are involved in evaluating proposals. By applying these techniques consistently across initiatives, organizations build a reliable foundation for investment decisions and resource allocation.

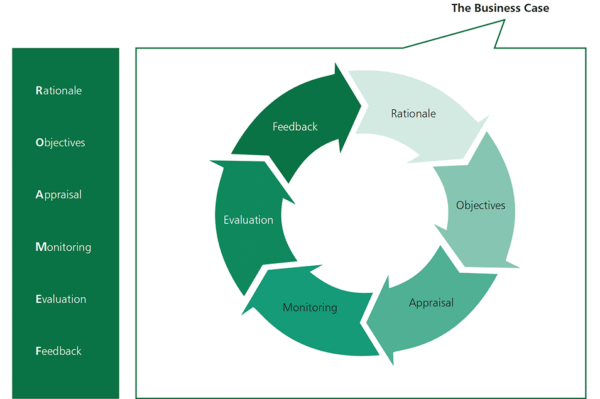

Developing and Managing the Business Case

The business case serves as the strategic and financial foundation upon which initiatives are built, approved, and governed. It is the primary instrument for justifying the allocation of organizational resources to a specific initiative, laying out the rationale in terms of financial investment, expected benefits, and alignment with broader objectives. More than a project justification, the business case offers a structured, evidence-based narrative that helps decision-makers assess risk, prioritize initiatives, and evaluate the likely return on investment.

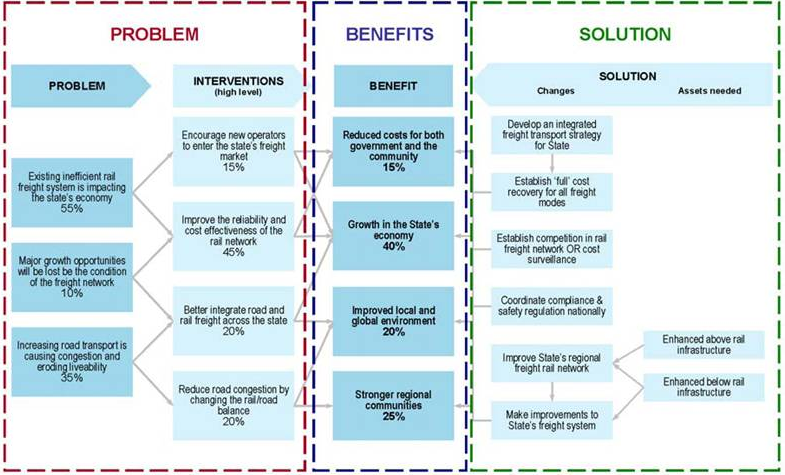

A strong business case connects strategic intent with operational execution. It does this by clearly articulating the need the initiative aims to address, evaluating possible solutions, selecting the preferred course of action, and forecasting the associated costs and benefits. Its role is to create confidence that the proposed initiative is both viable and worthwhile—not only in financial terms, but also in terms of risk exposure, strategic contribution, and organizational readiness.

While often viewed as a pre-approval document, the business case is in fact a dynamic asset that should evolve alongside the initiative. As more information becomes available, as delivery conditions change, or as financial performance varies, the business case is updated to reflect new realities. This flexibility allows it to continue supporting informed decision-making and financial control throughout the lifecycle of the initiative.

Core Components of a Business Case:

The effectiveness of a business case depends on its clarity, completeness, and rigor. While formats may vary across organizations, most high-quality business cases include several core components:

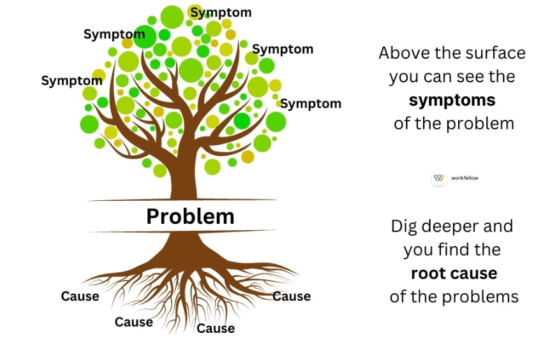

• Problem Statement: This section defines the issue or opportunity the initiative is designed to address. A well-crafted problem statement provides context for the proposal and helps stakeholders understand the urgency or strategic relevance of the initiative. It often includes evidence such as performance metrics, market trends, regulatory changes, or stakeholder concerns that validate the need for action.

• Options Analysis: Here, the business case outlines the various solutions that were considered, including the status quo (“do nothing”) as a baseline. Each option is assessed in terms of feasibility, cost, benefits, risks, and alignment with strategic goals. This comparative analysis ensures that the chosen solution is not selected arbitrarily but is demonstrably superior to alternatives. Techniques such as cost-benefit analysis or multi-criteria decision matrices are often used to support this evaluation.

• Preferred Solution: Based on the options analysis, the preferred solution is presented with supporting evidence. This section includes a description of how the solution will be implemented, what it will achieve, and why it represents the best use of available resources. The rationale may incorporate not only financial returns but also qualitative factors such as reputational gain, stakeholder satisfaction, or risk mitigation.

• Financial Appraisal: A critical component of the business case, the financial appraisal provides detailed estimates of the total investment required, including capital and operational costs, as well as projected benefits—whether in the form of revenue, savings, or efficiency gains. Techniques such as Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and payback period are used to support this appraisal, enabling consistent comparisons between initiatives.

• Implementation Plan: This section outlines how the initiative will be delivered, including key milestones, resource requirements, timelines, governance structures, and risk management strategies. The implementation plan ensures that the initiative is not only theoretically viable but also practically executable within the organizational context.

These components work together to create a comprehensive view of the initiative’s value proposition. A well-prepared business case does not merely request funding—it demonstrates that funding an initiative is a prudent and beneficial course of action for the organization as a whole.

The Business Case as a Living Document:

One of the most important but often overlooked features of a business case is its ability to evolve. Initial cost estimates, assumptions about benefits, and timelines are made using the best available data at the time of writing, but as the initiative unfolds, these inputs inevitably change. Treating the business case as a static, one-time deliverable risks undermining its relevance and accuracy.

By contrast, treating the business case as a living document allows for continuous refinement. As actual costs are recorded, projections can be adjusted. As stakeholder needs shift or external conditions evolve, assumptions can be revisited. Benefit forecasts can be recalibrated based on real-time performance or external feedback. This ongoing adaptation ensures that the business case remains a credible basis for decision-making throughout the initiative’s duration.

In practice, maintaining a living business case involves regular updates—typically aligned with project stage gates, reporting cycles, or major change requests. These updates allow financial and governance stakeholders to reassess the business rationale in light of emerging data and to make timely adjustments to scope, resources, or delivery methods as needed.

This approach not only supports better financial control but also promotes organizational agility. Initiatives that maintain an up-to-date business case are better positioned to respond to risk, adapt to change, and deliver outcomes that reflect current priorities rather than outdated assumptions.

Strategic Role in Governance and Decision-Making:

The business case occupies a central role in initiative governance. It provides the evidentiary basis for approvals, funding releases, and continued investment. During project reviews, performance is assessed not just against operational plans but also against the cost-benefit expectations set out in the business case. This ensures that strategic oversight is grounded in financial reality.

Many organizations incorporate formal checkpoints—such as stage-gate reviews or investment panels—at which the business case is reviewed and either reaffirmed or revised. These governance structures allow leadership to assess whether the initiative is still delivering its expected value or whether intervention is required. In some cases, the updated business case may support a change in direction, a scope reduction, or even a decision to halt the initiative if it no longer represents a sound investment.

By linking ongoing investment to real-time financial evidence, the business case becomes a tool for accountability. It enables senior stakeholders to ensure that resources are being used appropriately and that the initiative remains aligned with organizational priorities. This accountability also extends to external stakeholders—such as regulators, funding bodies, or shareholders—who may require assurance that initiatives are managed transparently and effectively.

In more mature environments, business cases are archived and reviewed collectively to support organizational learning. Comparing planned versus actual outcomes across multiple initiatives helps improve forecasting accuracy, identify systemic challenges, and refine investment appraisal methodologies.

Beyond the Financial Case: Broader Organizational Value:

While financial appraisal is central to the business case, it is not the only measure of value. Effective business cases consider a wider set of benefits and impacts—some of which may be difficult to quantify but are nonetheless strategically important. These can include:

• Enhanced customer satisfaction

• Improved compliance with regulatory or legal requirements

• Increased organizational resilience

• Support for sustainability goals

• Strengthened brand reputation or market positioning

Incorporating both quantitative and qualitative benefits ensures that the business case captures the full range of value an initiative is expected to deliver. This holistic view is especially important in public sector, non-profit, or mission-driven organizations where return on investment may not be purely financial.

Ultimately, the business case is a mechanism for ensuring disciplined investment. It bridges the gap between vision and execution, allowing strategic intent to be translated into financially sound, operationally feasible, and governance-approved action. It is through the business case that initiatives gain legitimacy, secure funding, and remain accountable for results. Managed effectively, it is not just a document—but a vital tool for responsible leadership and successful outcomes.

Funding Requests and Cost Management Practices

The transition from planning to execution in any initiative hinges on a single, critical gateway: the securing of appropriate funding. Without formal financial backing, even the most thoroughly developed business case remains a theoretical exercise. Funding approval is the mechanism by which an organization signals its commitment to the initiative, authorizing the use of resources and enabling work to begin. As such, the development of clear, credible, and strategically aligned funding requests is an essential practice in effective finance management.

Funding requests serve as the operational expression of the business case’s financial appraisal. They are designed to convert forecasts and recommendations into a structured proposal that meets the requirements of internal governance bodies, investment panels, or funding authorities. Their purpose is not only to obtain financial support but also to reinforce confidence that resources will be used responsibly and that the initiative will be managed in line with broader organizational goals.

Key Elements of a Robust Funding Request:

To be effective, funding requests must go beyond basic cost estimates. They must provide sufficient granularity, justification, and contextual awareness to support approval decisions and enable long-term financial control. Common elements include:

• Clear Breakdown of Required Funds by Category and Timeline: A comprehensive view of how much funding is needed, when it is needed, and for what specific purposes. This includes categorizing expenditure by type (e.g., personnel, equipment, technology, consultancy), by initiative phase (e.g., design, procurement, delivery), and across time periods. Phased funding requests are often preferred, enabling organizations to release funds incrementally as progress milestones are achieved.

• Justification for Expenditure, Linked to Expected Benefits: Each requested cost should be linked to a clear rationale that ties expenditure to anticipated value. This connection demonstrates that the requested funding is not arbitrary but grounded in a plan to deliver specific outputs or outcomes. It also allows for benefit realization planning to begin at the funding stage.

• Risk Analysis Related to Funding and Expenditure Patterns: Funding requests should acknowledge potential financial risks—such as price volatility, exchange rate fluctuations, or resource availability—and outline how these will be managed. This not only shows financial foresight but also gives stakeholders a more realistic view of the funding envelope required to accommodate uncertainty.

• Evidence of Alignment with Organizational Objectives: Effective funding requests demonstrate that the initiative supports strategic aims, such as market expansion, operational efficiency, regulatory compliance, or innovation. This alignment reinforces the case for funding by showing how the initiative contributes to broader organizational success.

Approval processes vary by organization, but most include some form of review or scrutiny, whether through finance committees, executive boards, or steering groups. Funding requests that clearly present the case for investment in a transparent and structured manner are far more likely to pass through these gateways successfully and with minimal delay.

Cost Categorization and Financial Structuring:

Once funding is approved, attention shifts to cost management—the process of ensuring that approved funds are used effectively, efficiently, and in alignment with the agreed-upon financial plan. A foundational element of this is cost categorization, which allows for detailed tracking and reporting across different areas of expenditure.

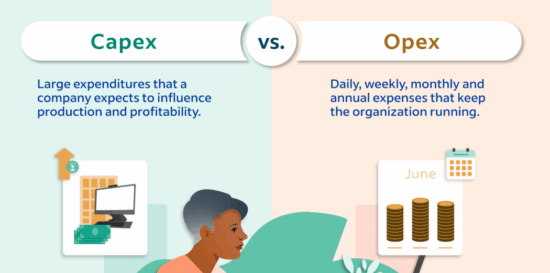

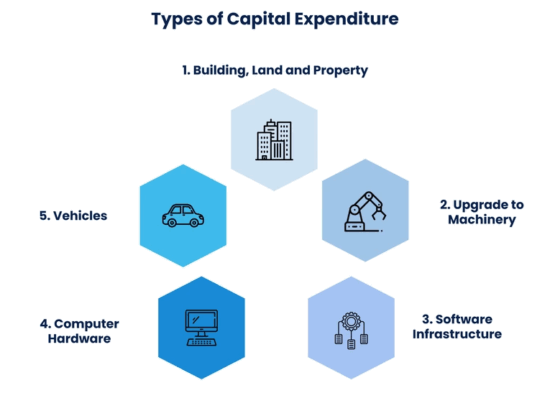

At the highest level, costs are often split into two primary categories:

• Capital Expenditure (CapEx): These are long-term investments intended to create future value, such as infrastructure development, system acquisition, or major equipment purchases. Capital costs typically appear on the balance sheet and are depreciated over time.

• Operational Expenditure (OpEx): These represent the ongoing costs of running the initiative, including salaries, utilities, consumables, training, and maintenance. Operational expenses are recorded in the profit and loss account as they are incurred.

Further detail is often introduced through secondary categorizations, such as:

• Direct Costs: Costs directly tied to the initiative, such as the salary of dedicated staff, vendor invoices, or materials procured specifically for the project.

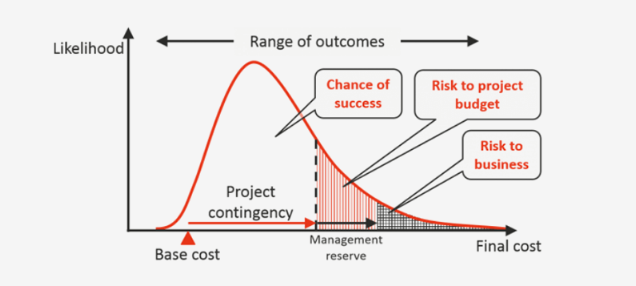

• Indirect Costs: Costs that are shared across initiatives or departments, including overheads like office space, utilities, or administrative support.

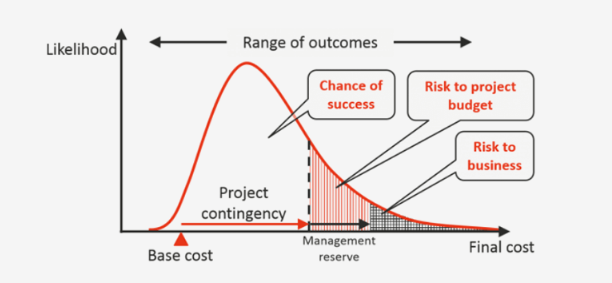

• Contingency Allocations: Financial buffers built into the budget to absorb unforeseen costs or risks. These are essential for maintaining stability under uncertain conditions and are often subject to strict governance controls before use.

A well-structured cost framework supports more accurate tracking, better forecasting, and clearer reporting. It enables organizations to identify cost drivers, assess the cost-efficiency of delivery methods, and compare actual spending to baseline budgets.

Ongoing Cost Management and Financial Control:

Effective cost management extends far beyond the initial budgeting phase. It is a continuous process that involves monitoring, evaluating, and adjusting financial performance throughout the lifecycle of the initiative.

Key practices include:

• Regular Financial Reporting: Periodic reports comparing actual costs to forecasted budgets are a cornerstone of transparency. These reports often include commentary on variances, explanations of cost increases, and projections for future expenditure.

• Variance Analysis: This technique involves comparing planned financial performance to actual results and analyzing deviations. Variance analysis helps identify areas of overspending or underspending and provides early warning signs of potential financial issues. It also supports root-cause analysis and continuous improvement in financial planning.

• Forecasting and Reforecasting: Forecasting is not a one-time exercise. Reforecasting based on new data, changes in scope, or emerging risks is vital for maintaining financial accuracy. It ensures that resources remain sufficient and appropriately allocated throughout the initiative.

• Milestone-Based Funding Releases: Many organizations implement funding controls that tie financial disbursement to the achievement of predefined milestones. This approach reduces financial risk and ensures that additional funding is only released when specific deliverables or outcomes are met.

• Change Control Mechanisms: As initiatives evolve, changes to scope or schedule may necessitate budget adjustments. Formal change control processes ensure that these adjustments are reviewed, justified, and approved in accordance with financial governance frameworks.

Promoting Efficiency and Value for Money:

Beyond financial discipline, cost management also involves a commitment to efficiency and value creation. Identifying ways to achieve outcomes at lower cost—or to increase value without increasing spend—is a central concern of finance professionals supporting initiative delivery.

Common efficiency strategies include:

• Supplier Negotiation: Renegotiating contracts, exploring competitive sourcing options, or leveraging purchasing consortia to reduce procurement costs.

• Process Optimization: Streamlining internal workflows or delivery processes to reduce labor or time inputs without affecting quality or output.

• Technology Leverage: Investing in tools or platforms that automate routine tasks or enhance productivity, leading to long-term operational savings.

• Resource Reallocation: Continuously assessing how resources are used and reallocating them to areas of higher impact or urgency where appropriate.

Efficiency gains can be reinvested into the initiative to enhance scope or accelerate timelines, or returned to the organization to support other priorities. The key is that cost management is not about rigid austerity, but about responsible financial stewardship that maximizes return on investment.

Enabling Accountability and Governance Through Cost Transparency:

Ultimately, effective funding and cost management practices enhance accountability. By maintaining clear records of how funds are allocated and spent, organizations create a transparent environment that builds stakeholder confidence. Financial data becomes a key input to decision-making, performance reviews, and external reporting, ensuring that all parties understand how financial resources are contributing to organizational success.

Cost transparency also supports stronger governance. Leadership teams, oversight bodies, and auditors rely on accurate, timely financial data to assess initiative health, identify emerging issues, and approve future investments. In regulated environments, the ability to demonstrate sound financial practices can also protect against reputational or legal risk.

Challenges, Risks, and Best Practices in Finance Management

Finance management provides a disciplined framework for controlling initiatives, enabling strategic decisions based on cost, value, and risk. However, despite the structure and methodologies in place, managing finance across the lifecycle of an initiative presents a unique set of challenges. These challenges stem from the inherent unpredictability of external factors, the complexity of internal dynamics, and the evolving nature of most initiatives. Even in well-governed environments, financial assumptions made at the outset can become outdated or invalid as conditions shift.

Understanding and anticipating these challenges is essential for strengthening financial resilience, improving the accuracy of projections, and safeguarding the integrity of investments. At the same time, adopting best practices helps organizations not only react to problems but actively prevent them—transforming finance management from a reactive process into a strategic, value-generating capability.

Common Challenges and Risks in Finance Management:

Several risks consistently surface across programs and projects, regardless of industry or size. These include:

• Uncertainty in Early-Stage Cost Estimation: One of the most persistent challenges is the uncertainty involved in estimating costs during the initiation and planning phases. At these stages, limited information and incomplete specifications make it difficult to produce accurate forecasts. As a result, initial budgets are often built on assumptions that may not hold true as the initiative progresses.

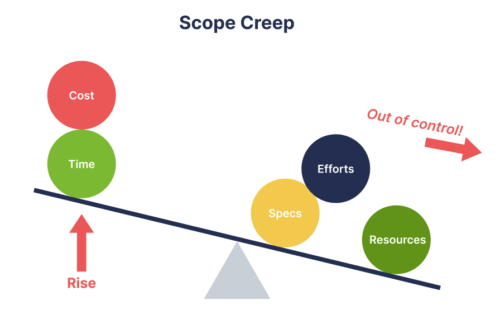

• Scope Creep and Change-Driven Cost Increases: As initiatives evolve, it is common for additional requirements, features, or deliverables to be added—often without a corresponding increase in budget. This phenomenon, known as scope creep, can significantly increase costs unless tightly controlled through change management and financial governance processes.

• Market Volatility and Supply Chain Disruptions: External economic conditions can quickly alter the financial landscape. Currency fluctuations, inflation, interest rate changes, and disruptions in global supply chains can drive costs higher than originally expected. These macroeconomic risks are often outside the control of the initiative team but have substantial financial implications.

• Overestimation of Benefits or Value: Just as underestimating costs can erode budgets, overestimating benefits can create false expectations about return on investment. This risk is especially pronounced in innovation-driven or technology-intensive initiatives where outcomes are speculative, and benefits may take longer to materialize than projected.

• Failure to Maintain a Living Business Case: A static business case becomes increasingly irrelevant as initiatives progress. If it is not regularly updated with current financial data, revised risk assessments, and reforecasted benefits, it can mislead decision-makers and undermine strategic oversight. Decisions may then be based on outdated or inaccurate information.

• Fragmentation of Financial Oversight: In large or multi-stakeholder initiatives, finance responsibilities can be dispersed across departments or functions, leading to inconsistencies in tracking, reporting, and accountability. Without integrated financial management, it becomes difficult to maintain a clear and accurate view of overall performance.

Each of these risks can lead to delayed timelines, cost overruns, reduced value delivery, or even the failure of the initiative. However, organizations can mitigate these issues by embedding proven finance management practices into their standard delivery approach.

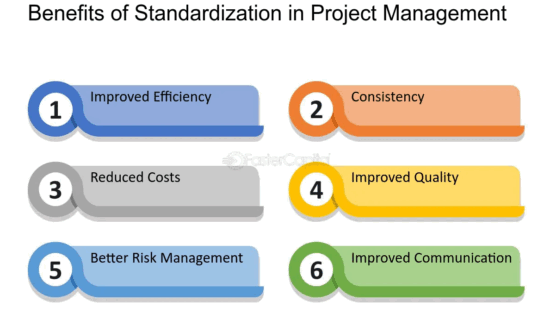

Best Practices in Finance Management:

Effective finance management is characterized by a set of interrelated behaviours and systems that promote accuracy, responsiveness, and alignment. These best practices strengthen financial discipline while providing the flexibility needed to respond to change.

1. Continuous Monitoring of Financial Performance Against Forecasts:

Ongoing financial monitoring is essential for maintaining control and visibility. Rather than relying solely on static budgets or annual reviews, continuous monitoring involves real-time tracking of actual spend against planned forecasts. This practice allows for the early detection of deviations, giving teams the opportunity to investigate causes and make adjustments before problems escalate.

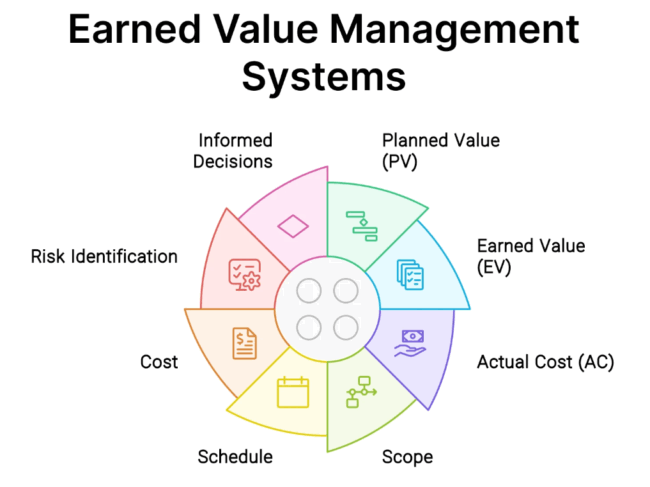

Key techniques include variance analysis, earned value management, and financial dashboards that provide up-to-date insights into costs, funding utilization, and burn rates. When combined with milestone tracking and risk monitoring, these tools ensure that financial health is assessed as part of regular initiative reviews.

2. Adaptive Planning and Reforecasting:

Flexibility in financial planning is a vital component of success. Conditions rarely remain constant across the lifecycle of an initiative. Therefore, organizations must be able to adjust financial forecasts and plans in response to changing internal priorities or external events.

Adaptive planning enables teams to revise cost projections, recalibrate funding schedules, and reassess benefit expectations based on the most recent data. It also allows for scenario planning, where multiple financial outcomes are modelled to understand how different risks or decisions may impact costs and value delivery.

The ability to reforecast accurately requires close collaboration between finance professionals and initiative teams, ensuring that emerging risks and opportunities are captured in a timely and transparent manner.

3. Transparent Reporting to Build Trust and Enable Informed Decision-Making:

Trust in financial reporting is a prerequisite for strong governance. Transparency does not simply mean sharing numbers—it means presenting them in a context that is meaningful, consistent, and aligned with decision-making processes.

Financial reporting should include clear explanations of variances, updates to forecasts, and commentary on key drivers of performance. It should also be tailored to the needs of different stakeholders—executive sponsors, steering committees, regulatory bodies—ensuring that each group has access to the data required to fulfil their oversight responsibilities.

Transparent reporting not only supports decision-making but also enhances accountability. It provides a record of how funds are being used, what value is being delivered, and where corrective action may be necessary.

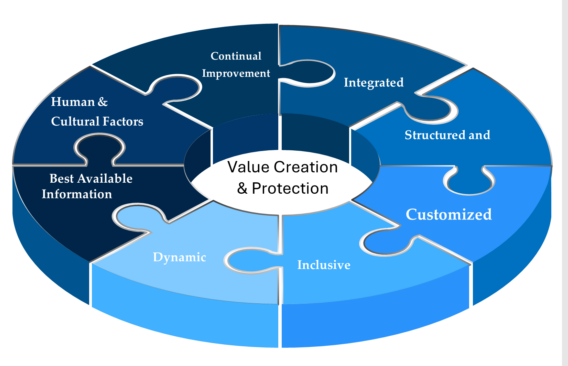

4. Integration with Broader Management Disciplines:

Finance management is most effective when it is integrated with other core disciplines such as risk management, resource planning, procurement, and stakeholder engagement. Financial decisions are rarely made in isolation; they are informed by timelines, dependencies, constraints, and stakeholder expectations.

For example:

• Risk assessments inform contingency planning and help shape financial buffers.

• Resource planning ensures that financial commitments align with workforce capacity and availability.

• Stakeholder feedback can influence prioritization and affect benefit assumptions.

• Procurement strategies can alter timelines and impact contract-related costs.

When finance is viewed as part of an integrated project ecosystem rather than a standalone function, it becomes more responsive, holistic, and strategically aligned.

Embedding a Proactive Finance Culture:

The ultimate goal of these best practices is to shift finance management from a passive, compliance-driven process to a proactive, value-focused capability. This requires a cultural orientation toward financial awareness, responsibility, and adaptability across all layers of the organization.

Proactive finance management means anticipating challenges rather than reacting to them, using data to inform choices, and continuously seeking ways to optimize outcomes. It means equipping delivery teams with the tools and knowledge to manage budgets effectively and empowering finance professionals to act as strategic partners rather than gatekeepers.

When financial acumen becomes embedded in initiative design, planning, and execution, organizations are better positioned to deliver consistent value, protect investments, and adapt to uncertainty. This approach ensures that finance management serves not just as a system of control—but as an enabler of long-term success.

Case Study: The Crossrail Project – Managing Costs Through Structured Financial Governance

The Crossrail project, now known as the Elizabeth Line, was one of the largest infrastructure developments in Europe. Initiated in the United Kingdom, this extensive transportation program aimed to deliver a high-capacity railway running across London, connecting major economic hubs and reducing travel times for millions of commuters. The program involved multiple stakeholders, complex engineering works, and a vast number of contractual arrangements.

Financial Challenges:

At the outset, Crossrail had a detailed business case with structured funding arrangements and cost projections. The business case set out the strategic justification for the project, highlighting anticipated economic benefits, congestion relief, and increased capacity on the rail network. However, as the project progressed, several factors—such as design modifications, supply chain issues, and system integration delays—led to significant cost escalations.

Finance Management Approach:

In response, financial governance was strengthened through tighter cost control measures, milestone-based funding releases, and continuous business case reviews. The original business case, which outlined capital expenditures, contingency budgets, and long-term operational costs, was revised multiple times to reflect real-time financial performance. Independent assurance bodies were engaged to validate the revised financial forecasts and reappraise the cost-to-benefit analysis as scope adjustments were made.

Outcomes and Lessons Learned:

Although the project experienced delays and budget overruns, the structured financial management approach allowed for greater visibility into cost drivers and accountability for financial decisions. This transparency enabled informed decisions about scope prioritization and the sequencing of works. The eventual delivery of the line brought about a significant boost to London’s transport capacity and urban regeneration, reaffirming the importance of maintaining a dynamic, well-managed business case throughout the lifecycle of complex initiatives.

Case Study: Cisco Systems – Using Business Cases to Guide Strategic Product Investment

Cisco Systems, a multinational technology conglomerate, frequently evaluates new technology investments and product development initiatives as part of its innovation strategy. One such project involved the development of a cloud-based collaboration platform intended to serve enterprise customers transitioning to hybrid work environments. Given the competitive nature of the market, the initiative carried both financial risk and strategic opportunity.

Financial Challenges:

Initial internal discussions revealed competing priorities for R&D funding. To secure backing, the project team was required to submit a robust business case detailing forecasted development costs, market demand validation, and a projected return on investment. Concerns were raised regarding the scalability of the proposed platform, infrastructure costs, and time-to-market.

Finance Management Approach:

The business case presented three possible technical paths, each with distinct cost implications. Financial modeling tools were used to evaluate these options based on internal rate of return (IRR), time-based break-even analysis, and sensitivity testing. A staged funding model was approved, tied to development milestones and market feedback checkpoints.

Throughout the development lifecycle, the business case was revisited and updated. As customer insights revealed new feature demands, the scope was adapted while cost implications were managed through vendor negotiations and process optimization. Finance and product teams worked closely to monitor spending, align funding with deliverables, and ensure ongoing justification for investment continuation.

Outcomes and Lessons Learned:

The product launched successfully and quickly gained adoption among large enterprises. Financial targets were met within the first 18 months, and the platform became a central offering within Cisco’s cloud portfolio. The case reinforced the value of structured business cases—not just for initial funding approval, but as an adaptive management tool that supports financial discipline and market responsiveness.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Strategic Finance Management in Change Initiatives

Strategic finance management forms the backbone of effective portfolio, program, and project delivery. It is not only a mechanism for tracking expenditure but a vital enabler of strategic change. By embedding financial thinking into the structure of change initiatives, organizations can better align resources to strategic priorities, drive value realization, and maintain financial accountability throughout the initiative lifecycle.

This part of the course introduces the foundational principles of finance management within complex delivery environments. It emphasizes the need to view finance as a dynamic, actively managed resource that influences decision-making, controls investment flows, and supports the achievement of long-term goals. Rather than approaching finance as a post-hoc reporting function, this perspective positions financial oversight as a proactive tool that guides initiative planning, execution, and governance.

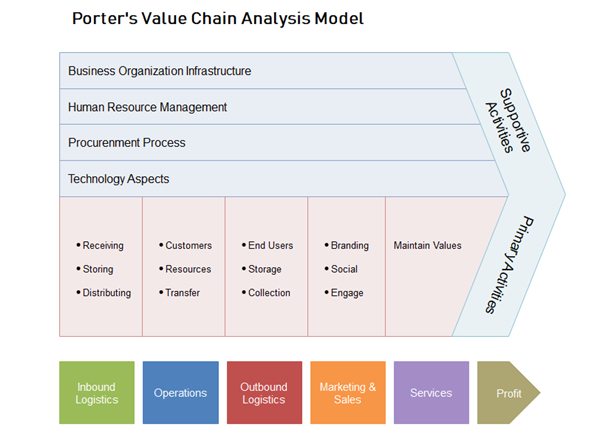

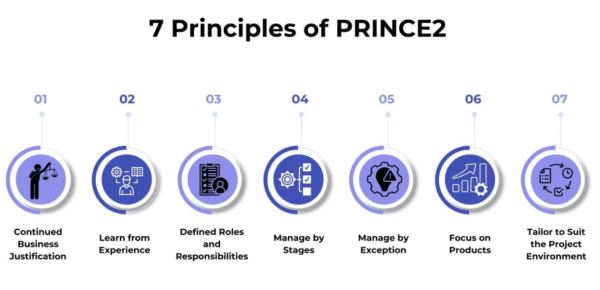

The manual explores the critical relationship between financial discipline and benefits realization. Through the application of strategic alignment matrices and value chain mapping techniques, it becomes possible to visualize the financial impact of each activity in relation to desired business outcomes. This approach supports the selection and prioritization of investments that deliver measurable value, while also providing a framework for tracking performance and assessing return on investment.

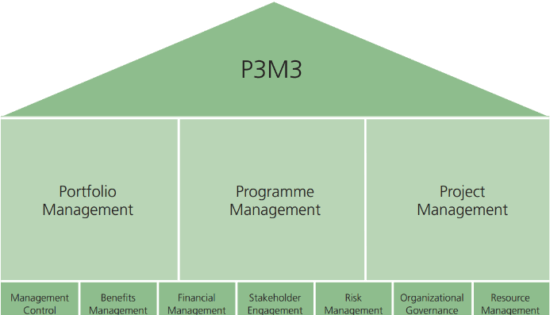

Financial governance is presented as a key component of effective oversight. Drawing on widely adopted standards such as MSP, MoP, P3M3, ISO 21500, and PMI’s PMBOK, the manual examines how organizations can integrate financial controls into existing governance frameworks. These models offer structured approaches to investment planning, cost control, and funding approval, tailored to the complexity of modern change portfolios. Sector-specific variations in global financial governance practices are also addressed, highlighting the diverse applications of strategic finance principles across industries.

To support practical implementation, the manual introduces tools such as financial governance templates and control point mapping across the investment lifecycle. These tools help formalize financial decision-making and enable consistent evaluation of whether initiatives remain aligned to business strategy. They also assist in identifying risks, ensuring accountability, and maintaining transparency with internal and external stakeholders.

By establishing a foundation in financial governance and strategic alignment, this manual positions finance as a driver of performance rather than a constraint. It highlights the importance of early engagement, continuous oversight, and structured investment controls in enabling successful outcomes. In doing so, it lays the groundwork for future exploration of funding mechanisms, cost management strategies, and business case development within the broader finance management discipline.

Chapter 2: Fundamentals of Cost Estimation and Budget Planning

Accurate cost estimation and disciplined budget planning are fundamental components of effective financial management within change initiatives. These practices enable organizations to allocate resources with confidence, support informed investment decisions, and establish a sound financial baseline for delivery oversight. Developing credible, well-structured budgets requires both methodological rigor and an understanding of the broader financial landscape in which initiatives operate.

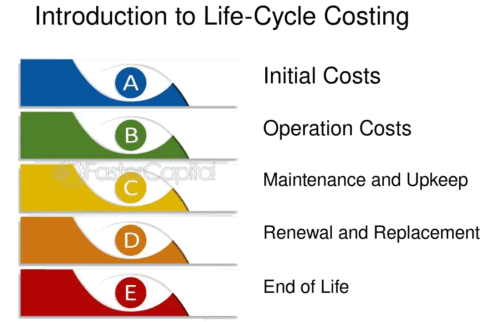

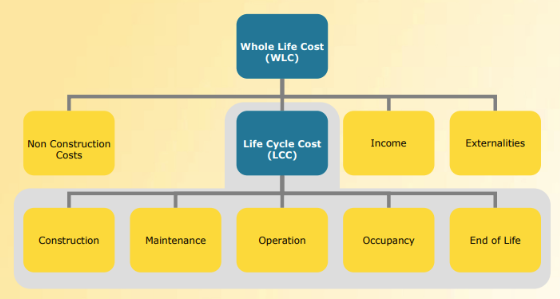

This part of the course explores the key principles, frameworks, and tools that underpin cost estimation and budgeting in project, program, and portfolio contexts. It begins by outlining the full spectrum of cost types that may be incurred across the initiative lifecycle. These include capital and operational expenditures, sunk costs, indirect charges, and contingency allocations. Recognizing and correctly categorizing these costs ensures that budget forecasts are comprehensive and capable of withstanding financial scrutiny.

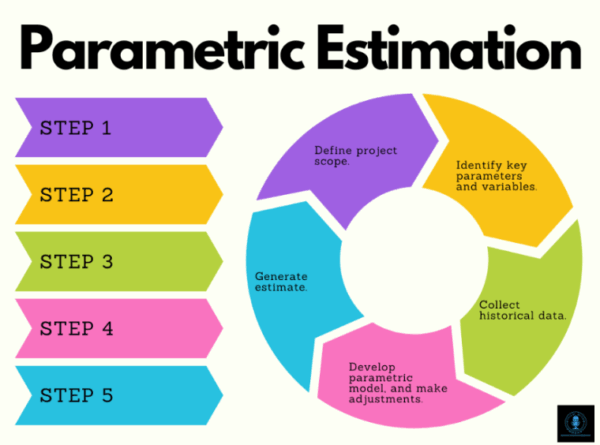

The manual then introduces widely used cost estimation techniques, such as analogous, parametric, and bottom-up approaches. Each method offers advantages depending on the nature, complexity, and maturity of the initiative. Emphasis is placed on selecting the most appropriate technique based on available data, historical benchmarks, and the degree of accuracy required at each planning stage.

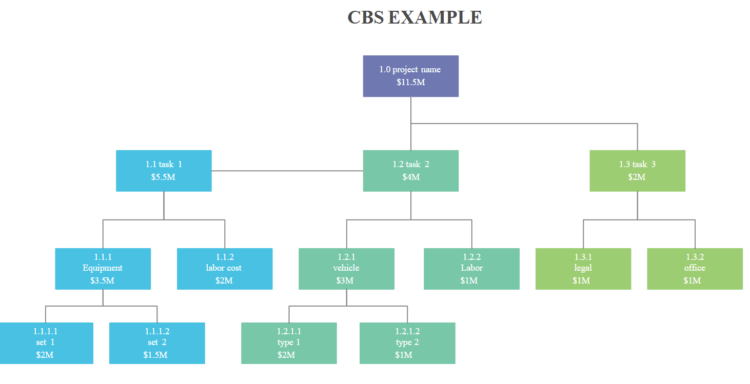

To support the development of structured financial plans, the manual highlights the use of Cost Breakdown Structures (CBS) and whole-of-life costing approaches. These models allow for the disaggregation of total costs into manageable components, making it easier to track, report, and adjust financial plans over time. The inclusion of sector-specific estimation frameworks reflects the diverse cost planning practices employed across different industries, while adherence to P3M3 and ISO-aligned budgeting processes ensures consistency with global standards.

Practical implementation is reinforced through the application of budgeting templates, estimation workbooks, and real-world cost modelling examples. These tools support the development of phased budgets that reflect initiative timelines, delivery risks, and anticipated resource flows. The ability to forecast funding requirements accurately over time enhances delivery assurance and supports the financial aspects of business case development and validation.

By applying robust estimation techniques and budget planning practices, organizations improve the credibility of their financial forecasts and the resilience of their initiatives. This manual promotes transparency in resource allocation and establishes a defensible financial foundation from which success can be managed, monitored, and measured.

Chapter 3: Funding Models and Investment Approval Processes

The ability to secure appropriate funding is central to the successful initiation and delivery of strategic initiatives. Navigating the complexity of funding models and organizational investment approval processes requires both technical knowledge and a strong understanding of governance expectations. When aligned to strategic objectives, funding decisions serve not only to enable delivery but also to safeguard organizational resources and maintain portfolio integrity.

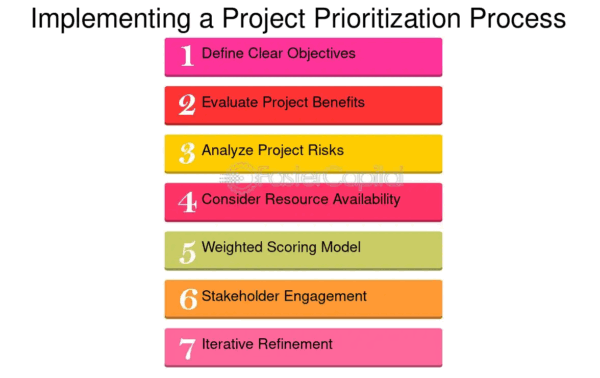

This section outlines the principles and practices that govern investment decision-making within project, program, and portfolio environments. It introduces a range of funding mechanisms and approval models, highlighting how these structures shape the flow of capital and determine whether initiatives proceed, are modified, or are rejected. An understanding of investment logic mapping, funding gate alignment, and portfolio prioritization ensures that funding submissions are not only financially sound but also strategically positioned.

The manual explores various frameworks used to structure investment decisions, including Gateway Reviews, Treasury Investment Decision Frameworks, and globally recognized sector-based models. These frameworks provide formal checkpoints that assess readiness, validate assumptions, and guide decision-makers on the release of funds across initiative stages. The integration of funding gates with delivery governance enhances oversight, promotes accountability, and supports phased investment approaches that align financial support with performance outcomes.

To support the development of high-quality submissions, the manual includes templates, worked examples, and tools for comparing investment options. These resources enable practitioners to prepare compelling funding requests that clearly articulate the value proposition, associated risks, and expected returns. Strategic alignment is emphasized throughout, reinforcing the importance of linking financial requests to business drivers, outcomes, and measurable benefits.

The inclusion of real-world case studies further illustrates the impact of effective and ineffective funding approaches. These examples reveal common success factors and pitfalls, such as clarity of purpose, consistency of financial data, and stakeholder engagement in the approval process.

Through the application of these models and tools, this manual establishes a foundation for financial decision-making that supports both initiative viability and organizational resilience. It highlights the role of funding in reinforcing delivery confidence, enhancing governance, and ensuring that resources are invested where they can deliver the most strategic value.

Chapter 4: Developing a Compelling Business Case

A strong business case serves as the foundation for investment decisions, providing the rationale for committing resources to an initiative. It is both a strategic and financial document—used to justify investment, evaluate options, and guide delivery throughout the initiative lifecycle. When constructed effectively, a business case enables organizations to prioritize wisely, allocate funding with confidence, and hold initiatives accountable for delivering measurable benefits.

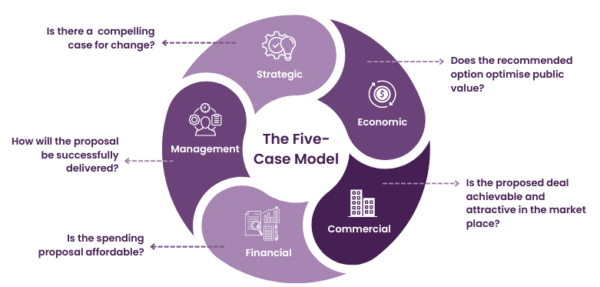

This section explores the development of business cases that are structured, evidence-based, and aligned to organizational objectives. It introduces recognized frameworks such as the Five Case Model, PMI’s business case structure, and PRINCE2 guidance, each offering a systematic approach to presenting value propositions. These frameworks help ensure that business cases are clear, consistent, and comprehensive in scope.

The manual emphasizes the importance of defining the problem or opportunity in precise terms, as this forms the basis for evaluating potential solutions. A compelling business case articulates the need for change, identifies and assesses viable options, and provides a reasoned recommendation supported by financial and non-financial analysis.

Financial appraisal plays a central role in the business case process. This includes conducting cost-benefit analyses, assessing financial viability versus affordability, and integrating risk and benefit considerations into the evaluation of each option. These elements support transparent comparisons between alternatives and ensure that proposed solutions offer value for money over the short and long term.

Practical tools are provided to support business case development, including templates for both three- and five-part models, cost-benefit analysis examples, and evaluation scoring sheets. These resources help formalize decision-making criteria and ensure that business cases are tailored to the complexity and scale of the proposed initiative.

The manual also draws on guidance from MoP and MSP to demonstrate how business cases evolve over time and remain central to governance throughout delivery. Rather than a static document, the business case is positioned as a dynamic tool—updated as new information becomes available and used to assess ongoing alignment between costs, risks, and benefits.

By reinforcing the principles of clarity, structure, and strategic alignment, this manual supports the development of business cases that resonate with decision-makers and stakeholders alike. It ensures that investment proposals are both credible and compelling, ultimately enabling organizations to invest wisely, manage risks effectively, and deliver the intended value.

Chapter 5: Financial Appraisal and Cost-Benefit Analysis

Financial appraisal provides a structured basis for evaluating the economic viability of potential initiatives. It enables decision-makers to compare investment options, assess value for money, and identify those initiatives most likely to deliver sustainable returns. A disciplined approach to financial appraisal supports both transparency and accountability, ensuring that investment decisions are grounded in evidence rather than intuition.

This part of the course outlines the core principles and techniques that underpin financial appraisal within organizational change contexts. It focuses on key methods such as Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Payback Period, providing practical guidance on how to calculate and interpret these indicators. These tools are essential for determining whether an initiative is financially viable, how long it will take to recover initial investment, and what return can be expected over time.

A critical component of appraisal is the application of discounted cash flow models, which account for the time value of money and enable more accurate comparisons between initiatives with differing timelines and cost structures. The manual also introduces sensitivity analysis, a technique that tests the impact of variable changes—such as costs, timelines, or benefit projections—on the overall financial viability of a proposal. Sensitivity testing supports robust decision-making by exposing potential risks and highlighting areas of financial uncertainty.

Frameworks such as the Treasury Green Book methodology and ISO 15686 ROI calculations are explored to demonstrate consistent, internationally recognized standards for investment appraisal. These frameworks provide guidelines for structuring appraisals, validating assumptions, and presenting findings to governance bodies. In addition, P3M3 value management processes are examined to show how financial appraisal aligns with broader portfolio and program value strategies.

To support practical application, the manual includes tools such as cost-benefit calculators, scenario testing models, and real-world financial templates. These resources help formalize financial evaluations and ensure that economic assessments are repeatable, auditable, and suited to the scale of the initiative under review.

By mastering these appraisal techniques, organizations enhance the credibility of their business cases and increase the rigor of their investment decisions. Financial appraisal becomes not just a finance function, but a strategic enabler—ensuring that resources are allocated based on clear value propositions, that risks are understood and quantified, and that initiatives are set up to deliver tangible, measurable outcomes.

Chapter 6: Integrating Risk, Contingency and Financial Controls

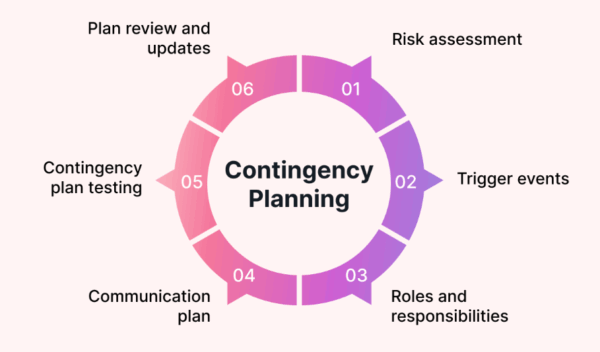

Effective financial management requires more than accurate estimates and structured budgets—it also demands proactive identification and mitigation of financial risk. Cost uncertainty, unforeseen events, and external disruptions are inherent to complex initiatives, and without integrated control mechanisms, these risks can erode value, delay delivery, or compromise outcomes. Embedding financial risk and contingency planning into all stages of the investment lifecycle is critical to sustaining delivery confidence and protecting organizational resources.

This section explores how financial risk can be systematically managed by incorporating it into business case development, cost estimation, and budgeting activities. The manual outlines the process of identifying potential financial risks, quantifying their impact, and applying structured mitigation strategies. By aligning risk management with financial control processes, initiatives gain greater resilience and adaptability in the face of changing conditions.

Key techniques such as risk-adjusted cost estimating are introduced, supported by methodologies like Monte Carlo simulation, which enables probabilistic forecasting of budget outcomes. These approaches allow for a more dynamic understanding of cost exposure, helping organizations assess the likelihood of overruns and build appropriate contingency allocations into financial plans.

The manual also examines frameworks including ISO 31000, which provides guidance on integrating enterprise risk management with financial governance, and P3M3 risk maturity models, which offer insight into how financial control practices evolve as organizational capability increases. These frameworks support the alignment of financial planning with overall risk appetite and oversight expectations.

Tools such as risk-cost matrix templates and risk-adjusted budget models are provided to help translate abstract risk concepts into actionable financial controls. These tools assist in prioritizing financial risks, applying cost buffers, and ensuring that business cases account for both known and emerging uncertainties.

Additionally, the manual highlights the distinction between assurance and audit processes, clarifying their respective roles in promoting financial integrity. Assurance activities are presented as proactive measures embedded in delivery governance, while audits offer retrospective validation of financial decisions and outcomes. Understanding the function of both supports stronger governance and reinforces accountability.

Lessons learned from historical cost overruns are also explored, providing practical examples of how inadequate risk integration can undermine financial performance. These insights reinforce the value of forward-thinking financial planning and strengthen the case for embedding contingency strategies into standard delivery practices.

By incorporating financial risk and control mechanisms into governance frameworks, this manual supports the development of robust, adaptable financial strategies. It enables organizations to anticipate disruption, respond effectively to change, and maintain confidence in their financial planning and investment decisions across the initiative lifecycle.

Chapter 7: Lifecycle-Based Financial Monitoring and Control

Ongoing financial oversight is essential to ensure that initiatives remain within defined cost parameters and continue to deliver expected value. Financial performance must be monitored systematically throughout the initiative lifecycle, with timely interventions applied where necessary to protect investment integrity. Consistent monitoring not only supports corrective action when variances occur but also provides assurance that benefits remain achievable and aligned to strategic objectives.

This part of the course outlines how structured financial monitoring practices can be integrated into portfolio, program, and project environments. It introduces key metrics, reporting methods, and performance management tools that support the real-time tracking of expenditure and progress. At the core of this approach is Earned Value Management (EVM)—a performance measurement methodology that provides a quantitative view of cost and schedule variance.

Using EVM models based on standards such as PMI guidelines and ISO 21508, the manual demonstrates how to calculate cost performance indicators and compare actual progress to planned expenditure. These insights enable delivery teams and governance bodies to detect deviations early and implement corrective actions before they affect outcomes. Variance analysis techniques are explored in detail, providing a structured way to assess root causes and inform financial recovery planning.

Lifecycle-based monitoring also connects financial data to benefits realization. By linking expenditure to planned outcomes, organizations can assess whether investments are delivering value in line with expectations. This alignment ensures that financial performance is not managed in isolation, but in conjunction with strategic benefit tracking and delivery assurance.

The manual includes models for lifecycle financial monitoring, emphasizing how financial control practices evolve from planning through to closure. Each stage of the lifecycle presents unique monitoring requirements—ranging from baseline tracking during initiation to benefits review during post-completion phases. Practical tools such as EVM dashboards, financial health checklists, and monthly reporting templates are provided to support implementation.

Through structured financial monitoring, organizations gain the visibility needed to maintain control over complex initiatives. It enables evidence-based decision-making, reinforces governance, and ensures that investment remains aligned to delivery expectations. By embedding these practices into standard operations, financial performance becomes a continuous, integrated component of initiative management—enhancing both accountability and value delivery.

Chapter 8: Business Case as a Living Document

In dynamic delivery environments, the original rationale for investment must be revisited and validated as conditions evolve. The business case, far from being a static approval document, serves as a continuous reference point for alignment between strategic objectives, delivery performance, and realized value. Treating the business case as a living document allows for agility, transparency, and sustained decision integrity throughout the initiative lifecycle.

This section highlights the critical role of ongoing business case maintenance as a governance tool. As initiatives progress, changes in scope, risk, cost structures, or market conditions can significantly alter the assumptions upon which funding and delivery plans were based. In response, the business case must be actively reviewed, revised, and communicated to ensure it reflects the current reality of the initiative and maintains its relevance to stakeholders and decision-makers.

Frameworks such as MoP and MSP emphasize dynamic case governance, encouraging the integration of business case reviews into health checks, gate reviews, and major checkpoint events. These governance moments offer structured opportunities to assess whether continued investment remains justified and whether anticipated benefits are still achievable under evolving conditions.

The manual introduces change control and refresh procedures, which formalize the process of reviewing and updating business case components. Triggers for review may include major delivery milestones, cost escalations, risk profile changes, or shifts in strategic direction. Ensuring that these triggers are recognized and acted upon reinforces financial discipline and supports responsive governance.

Key tools such as business case update logs, assurance review templates, and stakeholder briefing packs are included to facilitate transparent revisions and engagement. These resources enable delivery teams to document changes clearly, communicate their implications effectively, and secure alignment across stakeholder groups.

A focus is also placed on benefit-cost revalidation, which involves reassessing the balance between investment inputs and intended outcomes. Engaging stakeholders in this process ensures continued buy-in, reinforces the value proposition, and enhances decision quality at key junctures in the initiative’s progression.

By embedding the concept of the business case as a living document into financial and delivery governance, organizations can respond confidently to change while maintaining a disciplined focus on value. This approach strengthens oversight, supports real-time decision-making, and ensures that investment continues to serve strategic intent throughout the course of transformation.

Chapter 9: Stakeholder Engagement and Financial Transparency