Adaptive Leadership – Workshop 4 (Organizational Integrity)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Adaptive Leadership is provided by Dr. Wade Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 12 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Dr. Wade started his career serving 20 years in senior leadership positions with a focus on change management. He then excelled in the management consulting and leadership development industries for the past eight (8) years, first as an Executive Vice-President and then with his own leadership development company.

Dr. Wade been involved with leadership development, change management, and generational and cultural mega-trends and meta-narratives since the mid-90’s. He is a passionate leadership futurist and expert in adapting to generations, culture, and the future of leadership. As an expert at the forefront of the latest leadership development training, Dr. Wade’s subject matter and proven process will empower you and your organization to successfully develop the critical skills necessary to thrive in today’s leadership environment.

Dr. Wade has extensive experience training leaders in various sectors from healthcare to technology to finance and more. This course, and the subsequent subject matter, will guide course participants through many of the pitfalls and struggles in the modern leadership environment and enable them to master adaptive solutions. Each participant will feel inspired and will have gained practical understanding and actionable steps in relation to adaptive leadership.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

A fundamental principle in adaptive leadership is the construction of organizational integrity, which is sometimes referred to as organizational justice. Organizational integrity refers to how employees perceive honesty, transparency, and fairness in the workplace. During times of change, employees will need to feel a sense of safety and security from leaders to help traverse the uncertainty that comes with change. If employees do not feel a sense of transparency, honesty, and fairness they will grumble and complain, not just about the proposed changes, but about the leaders and leadership team themselves and their “poor handling” of the issues. An adaptive leader must therefore, intentionally foster a culture of honesty, humility, and psychological safety to help their team members feel a sense of wellbeing through this volatile time. Attempts at managing change often get derailed because leaders are not adept at building and communicating a sense of organizational integrity. Adaptive leaders will strive to implement the best strategies for the good of the organization. Furthermore, adaptive leaders must explore the best ways to communicate and implement adaptive changes. In this module, course participants will become well versed in building a culture of organizational integrity. The culture of the organization trumps well-intentioned plans. In the words of Peter Drucker, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Participants will come away with a thorough understand of culture creation and the values that makeup organizational integrity. They will grasp the importance of transparent and honest communication and the need for the leaders themselves to live the organizational principles and values they promote. Course participants will be able to immediately implement their knowledge of culture and organizational integrity.

Objectives

01. Organizational Integrity: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Establishing Security : departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Honesty Communication: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Organizational Fairness : departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. Organizational Humility: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Cultural Integrity: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Communicating Integrity: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Leadership Integrity: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Adaptive Integrity : departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Measuring Integrity: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Overcoming Barriers: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Sustainable Culture: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. Organizational Integrity: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Establishing Security : Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Honesty Communication: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Organizational Fairness : Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. Organizational Humility: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Cultural Integrity: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Communicating Integrity: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Leadership Integrity: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Adaptive Integrity : Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Measuring Integrity: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Overcoming Barriers: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Sustainable Culture: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Organizational Integrity.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Establishing Security .

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Honesty Communication.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Organizational Fairness .

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Organizational Humility.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Cultural Integrity.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Communicating Integrity.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Leadership Integrity.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Adaptive Integrity .

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Measuring Integrity.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Overcoming Barriers.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Sustainable Culture.

Introduction

Organizational Integrity is a critical pillar of adaptive leadership, particularly during times of uncertainty and transformation. It refers to the extent to which an organization consistently upholds values such as honesty, transparency, fairness, and accountability in both words and actions. While the term has evolved over time, its roots are found in disciplines such as organizational justice, ethics, and culture, all of which intersect to shape how employees experience trust, leadership credibility, and fairness within the workplace.

The Rise of Organizational Justice

The concept of organizational justice gained prominence in the late 20th century as scholars in organizational psychology began to systematically explore how perceptions of fairness influence employee behavior, motivation, and trust. Pioneering researchers like Jerald Greenberg and John Thibaut helped define the key dimensions of justice in the workplace:

• Procedural justice refers to the perceived fairness of the processes used to make decisions. Do employees believe that rules are applied consistently, that their voices are heard, and that decisions are free from bias?

• Distributive justice focuses on the fairness of outcomes—such as pay, promotions, or workloads—and whether these are distributed equitably based on input and performance.

• Interactional justice pertains to the quality of interpersonal treatment employees receive, especially in how respectfully and truthfully information is communicated by leaders.

These three components helped organizations understand that fairness is not just about end results, but about how people are treated along the way. A workplace that scores highly on all three is more likely to foster engagement, loyalty, and discretionary effort.

As this research matured, its application extended beyond academic interest to the realm of practical leadership and corporate governance. During the 1980s and 1990s, many organizations began linking justice to ethical conduct and trust-building. This was especially important as globalization, deregulation, and technological change introduced greater complexity and competition into the business environment. Trust became a form of currency—not only internally among employees, but externally with customers, investors, and the broader public.

Then, in the early 2000s, a wave of high-profile corporate scandals—including those involving Enron, WorldCom, and Arthur Andersen—exposed the devastating effects of unethical leadership and a lack of organizational integrity. These events revealed how fragile trust can be when leadership fails to align words with actions. Billions in shareholder value were lost, reputations were destroyed, and public trust in corporate leadership plummeted.

In response, there was a global push toward ethics reform in business. Regulatory changes such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the U.S. were introduced to improve financial transparency and executive accountability. But beyond legal compliance, many organizations began codifying internal value systems, launching ethics programs, appointing Chief Ethics Officers, and embedding organizational justice principles into HR and leadership development practices.

This shift marked a key turning point: organizations began to understand that sustainable performance is deeply tied to perceived fairness and trust. Without a culture that supports open communication, ethical behavior, and consistent decision-making, even the most sophisticated business strategies can unravel.

For today’s adaptive leaders, the legacy of organizational justice research and post-scandal reforms serves as a reminder: integrity isn’t optional. It is a strategic imperative, especially in times of change when people are watching closely to see whether leaders uphold the values they profess.

Leading Through Change with Trust and Values

Today, organizational integrity is more than a moral ideal—it is a strategic asset. In a fast-changing business environment characterized by disruption, complexity, and diverse stakeholder expectations, employees and customers alike are attuned to how organizations behave, not just what they produce. A culture of integrity ensures that values are not merely slogans but living principles reflected in everyday actions, decision-making, and leadership behavior.

For adaptive leaders, cultivating organizational integrity is especially vital. Adaptive leadership, by nature, calls for navigating complex challenges that lack clear solutions. This often involves making tough decisions, confronting entrenched norms, and guiding teams through discomfort and ambiguity. In such conditions, people need psychological safety—a sense that they can trust leadership, express concerns, and feel heard. Without integrity, efforts at transformation can falter. Employees may resist change not because they dislike the change itself, but because they distrust the way it is being led.

Organizational integrity also contributes to long-term engagement, resilience, and innovation. When individuals perceive fairness, consistency, and ethical behavior, they are more likely to commit to shared goals, collaborate across silos, and go above and beyond in their roles. On the other hand, perceived hypocrisy or favoritism can erode morale and escalate into cultural dysfunction.

This workshop explores how adaptive leaders can intentionally shape cultures grounded in integrity. Participants will examine the values that underpin ethical workplaces, the communication styles that support transparency, and the leadership behaviors that build trust. The goal is not only to understand organizational integrity conceptually, but to learn how to operationalize it—especially during change, when credibility is most at stake.

The Business Case for Integrity

Organizational integrity is not just a philosophical or ethical ideal—it is a measurable driver of business success. In an era defined by rapid change, social transparency, and stakeholder scrutiny, integrity has become a foundational element of organizational performance, innovation, and brand trust. Leaders who invest in building a culture of integrity are not only doing what is right—they are also doing what is smart.

Performance and Productivity

Studies consistently show that workplaces perceived as fair, transparent, and ethically grounded perform better. When employees believe that leadership acts with integrity, they are more engaged, motivated, and committed. According to research by the Corporate Executive Board, companies with high-integrity cultures outperform others by as much as 10% in shareholder return. These environments foster psychological safety, enabling employees to contribute ideas, challenge norms, and take initiative without fear of unfair repercussions.

Trust and Retention

Trust is a currency in today’s knowledge economy, and organizational integrity is its backbone. When leaders consistently align their actions with organizational values, they build trust—not just within teams, but also across departments and stakeholder groups. Trusted organizations enjoy higher retention, lower absenteeism, and greater internal cohesion. A 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer report found that 73% of employees expect CEOs to act on societal issues, and that trust in leadership directly affects employee loyalty and advocacy. In contrast, perceived hypocrisy can lead to attrition, disengagement, and internal resistance to change.

Innovation and Risk-Taking

A culture rooted in integrity supports experimentation, idea-sharing, and innovation. When employees trust that their voices will be respected and their failures treated fairly, they are more likely to take calculated risks and offer creative solutions. Integrity fosters an open environment where feedback flows freely and diverse perspectives are welcomed.

Case Study: Patagonia

Patagonia is a compelling example of how organizational integrity can fuel innovation, employee engagement, and brand loyalty. Known for its strong commitment to environmental and social responsibility, Patagonia embeds its values into every layer of its operations—from supply chain transparency to environmental activism. The company encourages employees to challenge the status quo, question business practices, and propose mission-aligned innovations that contribute to both business success and social impact.

One notable initiative was the launch of the Worn Wear program, which promotes repair and reuse of outdoor clothing to reduce consumer waste. This idea emerged from internal conversations about sustainability and was championed by employees who believed the brand should model responsible consumption. Rather than viewing this program as a threat to sales, Patagonia embraced it as a reflection of its integrity-driven mission.

The result is a purpose-led culture where innovation is not only welcomed, but expected. This alignment between values and action has strengthened employee morale and built deep trust with customers. Patagonia’s transparency, ethical stance, and environmental leadership have helped it stand out in a crowded market, proving that integrity can be both a moral compass and a competitive advantage.

Brand Reputation and Crisis Resilience

Organizational integrity also plays a critical role in external perception. Brands seen as ethical and authentic tend to earn stronger customer loyalty, attract top talent, and enjoy goodwill in times of crisis. Conversely, breaches of integrity can cause long-term reputational damage. The collapse of Volkswagen’s diesel emissions cover-up, for instance, not only cost billions in fines but severely tarnished public trust. Similarly, Facebook (now Meta) faced global backlash over data privacy concerns, sparking debates around corporate responsibility and user rights.

The business case for integrity is clear: it enhances performance, deepens trust, unlocks innovation, and protects brand value. Adaptive leaders must view integrity not as an abstract value but as a strategic tool—one that sustains organizational health and resilience in the face of complexity. In doing so, they cultivate not only a productive workforce but a purpose-driven legacy built on trust and transparency.

The Future of Organizational Integrity

As the business landscape becomes increasingly complex, globalized, and socially conscious, organizational integrity is poised to take on an even more central role in how companies operate, compete, and lead. No longer confined to the realm of compliance or ethics programs, integrity is becoming a dynamic, strategic capability—one that organizations must actively cultivate to earn trust, attract talent, and sustain innovation in a rapidly evolving world.

One of the most significant drivers shaping the future of organizational integrity is radical transparency. With the rise of digital platforms, whistleblowing forums, and real-time reporting, businesses are under constant public scrutiny. Stakeholders—from consumers to employees to investors—now have unprecedented access to information, and they expect organizations to act consistently with their stated values. In this new era, integrity can’t be managed through carefully crafted PR statements; it must be lived and demonstrated in day-to-day decisions, internal policies, and leadership behavior.

In parallel, younger generations entering the workforce are raising the bar for integrity-driven leadership. Millennials and Gen Z professionals place high importance on values alignment, ethical decision-making, and corporate social responsibility. These employees are more likely to question leadership, demand transparency, and leave organizations whose actions contradict their messaging. For forward-looking companies, this generational shift represents an opportunity—not a threat—to reimagine workplace culture with integrity at its core.

The future will also require integrity to be more inclusive and intersectional. Organizations can no longer separate ethical behavior from broader social dynamics like equity, inclusion, and environmental sustainability. Integrity must expand to account for how fairly people are treated across lines of race, gender, ability, and background, and how organizational practices impact the wider community and planet. This holistic view demands that leaders confront difficult questions, acknowledge blind spots, and continuously learn in partnership with diverse stakeholders.

Technological change is another factor reshaping integrity’s future. As artificial intelligence, automation, and data analytics become embedded in decision-making, questions of fairness, bias, and accountability grow more complex. Ethical frameworks will need to evolve to ensure that technology serves human interests rather than undermines them. Companies that proactively embed ethical oversight into product design, data governance, and algorithmic transparency will distinguish themselves as integrity-driven innovators.

Finally, the future of organizational integrity will be defined by adaptive leadership—the ability of leaders to model humility, respond with agility, and prioritize long-term trust over short-term gain. As crises and disruptions become more frequent, stakeholders will look for signs of consistency, honesty, and care in how organizations respond. Leaders who can navigate uncertainty with transparency, courage, and principle will set the new standard for organizational excellence.

In summary, the future of organizational integrity is both challenging and promising. It calls for deeper alignment between purpose and practice, stronger ethical leadership, and a redefinition of success that values trust, inclusion, and sustainability. Organizations that rise to this challenge won’t just survive—they’ll earn the enduring respect and loyalty of those they serve.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Organizational Integrity

This chapter introduces organizational integrity as a foundational principle of adaptive leadership. Integrity is more than individual honesty—it is the alignment between an organization’s values, behaviors, and systems. In environments of change and uncertainty, integrity becomes essential for building trust, psychological safety, and sustained engagement. Leaders who demonstrate fairness, transparency, and consistency create cultures where people feel secure, heard, and motivated to contribute—critical conditions for navigating complex, adaptive challenges.

Participants will first explore what organizational integrity truly means. While often mistaken for personal ethics, integrity in an organizational context is about how consistently an organization lives its stated values through its policies, decisions, and cultural norms. Integrity becomes visible in how leaders handle mistakes, deliver feedback, and uphold fairness across the board. When these values are upheld, they foster credibility and trust; when they are violated, resistance, cynicism, and disengagement follow.

The chapter then connects integrity to psychological safety and trust—two vital elements for high-performing, resilient teams. Participants will learn how leadership behavior sets the tone for openness, inclusion, and risk-taking. Integrity, when practiced consistently, empowers employees to speak up, offer ideas, and admit mistakes without fear of judgment.

The chapter also examines how integrity directly influences change readiness and employee engagement. When employees believe leadership is acting with integrity, they are more likely to buy into change efforts. Engagement rises when people trust that change is being led fairly and transparently.

Finally, participants will learn to recognize signals of integrity failure—such as inconsistent messaging, lack of accountability, or suppressed dissent. These red flags erode trust and can compromise performance, innovation, and morale if left unaddressed.

By the end of this chapter, participants will be equipped to identify where integrity exists (or is lacking) in their own organizations. They will understand the critical role integrity plays in leading through complexity, and begin developing the awareness and practices needed to cultivate high-integrity environments. This sets the stage for the deeper leadership work to follow in the program.

Chapter 2: Establishing Security

In times of adaptive change, one of the most pressing needs for employees is a sense of security—the feeling that, even as systems and structures evolve, they remain grounded in something stable and trustworthy. Change brings with it ambiguity, and without clear leadership, people can become anxious, confused, or disengaged. This chapter explores how leaders can intentionally foster stability and predictability by practicing organizational integrity and demonstrating consistency in words, actions, and decisions.

Participants will first explore why security matters during adaptive change. Unlike technical change, adaptive challenges require people to let go of what they know and embrace the unfamiliar. This emotional disruption often leads to fear-based behavior unless leaders create an environment of safety and reassurance. Establishing security does not mean eliminating discomfort—it means providing enough clarity and consistency to help people move forward with confidence.

Next, the chapter examines how organizational integrity supports stability. When leaders act in alignment with values, apply policies fairly, and communicate honestly, they create a sense of reliability—even when circumstances remain fluid. Integrity provides a steady framework that reassures people that they won’t be blindsided or overlooked.

The chapter then explores the power of consistent messaging. In uncertain times, consistent communication helps employees stay focused and reduces speculation. Leaders will learn how to reinforce core messages across all levels of the organization and how values-driven communication builds trust—even when answers are incomplete.

The chapter then explores the power of consistent messaging. In uncertain times, consistent communication helps employees stay focused and reduces speculation. Leaders will learn how to reinforce core messages across all levels of the organization and how values-driven communication builds trust—even when answers are incomplete.

Finally, participants will learn to recognize and respond to signs of employee insecurity. Insecurity may appear through withdrawal, hyper-criticism, rumor-spreading, or hesitation to contribute. Leaders must learn to spot these subtle signals and respond with empathy, visibility, and reassurance. Offering clarity where possible—and acknowledging ambiguity when necessary—builds credibility and helps restore confidence.

Throughout the lesson, participants will reflect on how their own leadership behavior can influence the emotional climate of their teams. They will gain practical tools for reinforcing a secure environment, managing communication, and aligning their actions with the organization’s values.

By the end of this chapter, participants will understand that creating a secure environment is not about controlling outcomes—it’s about reinforcing stability through integrity, consistency, and care. These are essential leadership practices that help people stay grounded, engaged, and ready to navigate the challenges of adaptive change.

Chapter 3: Honesty Communication

In times of adaptive change, honest communication becomes one of the most vital leadership tools for maintaining trust, clarity, and engagement. This chapter explores honesty not just as a personal virtue, but as a strategic leadership behavior—one that demonstrates integrity, builds credibility, and creates stability, even when full certainty is not available.

Participants will begin by exploring why honesty matters. In high-pressure, evolving situations, employees don’t expect leaders to have all the answers—they expect them to be truthful about what is known, what is uncertain, and what the organization is doing to move forward. Honest communication affirms respect, enables psychological alignment, and prevents the misalignment and confusion that often arise when messages are vague or overly polished.

The chapter then examines the cost of withholding or distorting information. From speculation and disengagement to the erosion of trust, communication pitfalls can quickly destabilize a change effort. Leaders will learn how silence, inconsistency, or misleading messaging—even when well-intentioned—can create lasting damage to morale and cohesion.

To address this, participants will gain practical techniques for honest, effective communication during uncertainty. This includes acknowledging what’s unknown, using plain and compassionate language, encouraging two-way dialogue, and aligning communication across leadership levels. These skills help reduce fear, manage expectations, and foster an environment where employees feel respected and informed.

Next, the module focuses on balancing candor with compassion—a crucial skill for delivering difficult news. Being honest doesn’t mean being harsh; it means communicating clearly while recognizing and validating the emotional impact on others. Leaders will explore how to prepare thoughtfully, deliver difficult messages with empathy, and remain present and available for ongoing support.

Throughout the chapter, real-world examples and reflective exercises help ground the learning in lived experience. Case studies highlight both the risks of dishonest communication and the power of honest leadership during uncertain times.

By the end of this session, participants will understand how honesty reinforces organizational integrity, reduces confusion, and strengthens relationships. They will be equipped with the mindset and tools to communicate truthfully, even in complex and emotionally charged situations—fostering a culture of trust that is essential for adaptive leadership to succeed.

Chapter 4: Organizational Fairness

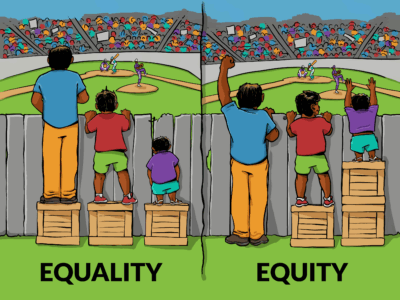

In adaptive leadership, fairness is not just an ethical principle—it’s a strategic practice that shapes how people interpret change. During periods of uncertainty, employees don’t only assess what decisions are made, but how and why they are made. When leadership actions are perceived as fair, people are more likely to remain engaged, trust leadership, and contribute positively to the organization’s transformation. Conversely, perceptions of unfairness—whether in workload distribution, opportunity access, or recognition—can quickly erode morale, trigger resistance, and fracture cohesion.

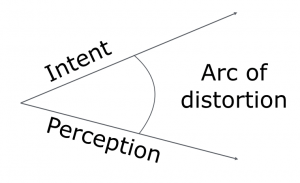

This chapter explores fairness as a visible demonstration of integrity, emphasizing that equitable leadership is not about treating everyone the same, but about meeting people where they are. Participants will learn to differentiate between equity and equality, applying this understanding to real-world scenarios where people have diverse needs, challenges, and contributions. The chapter also addresses fairness in resource allocation—an especially sensitive task during change and scarcity—and provides strategies for making transparent, values-based decisions that maintain credibility and trust.

Another core theme is how fairness influences team morale. When employees feel respected, included, and fairly treated, trust deepens, motivation strengthens, and a sense of belonging grows. Leaders will explore how consistent, inclusive practices help maintain these conditions and prevent disengagement, especially among underrepresented groups.

Another core theme is how fairness influences team morale. When employees feel respected, included, and fairly treated, trust deepens, motivation strengthens, and a sense of belonging grows. Leaders will explore how consistent, inclusive practices help maintain these conditions and prevent disengagement, especially among underrepresented groups.

Realistic case studies, reflective questions, and practical tools help participants apply fairness in complex leadership contexts—such as budget cuts, restructuring, and evolving team roles. The chapter also encourages leaders to close the gap between intention and perception by clearly communicating the rationale behind decisions, welcoming feedback, and adjusting approaches when unintended impacts arise.

Participants will leave with a deeper understanding that fairness is not static—it’s relational, visible, and responsive. It requires empathy, transparency, and consistency. When fairness is perceived, it becomes a powerful driver of resilience, trust, and engagement—essential conditions for navigating change successfully.

By the end of the chapter, leaders will be equipped to embed fairness into everyday leadership decisions, ensuring that their actions align with values, foster cohesion, and promote a workplace where all employees feel respected, valued, and supported during change.

Chapter 5: Organizational Humility

This chapter explores humility as a defining strength of adaptive leadership—especially in times of change and complexity. Far from being a sign of weakness, humility is reframed as a core leadership capability that builds trust, fosters collaboration, and strengthens organizational integrity. Participants will learn that humility is not about modesty for its own sake, but about being self-aware, open to feedback, and grounded in a shared purpose.

The module begins by redefining strength in leadership. Traditional models often prize certainty and authority, but in adaptive contexts, where ambiguity and rapid change are the norm, the ability to admit limits, invite diverse input, and learn publicly becomes essential. Humble leaders foster psychological safety, empowering teams to speak up, innovate, and take risks without fear.

Participants will also explore how humility is demonstrated through transparent acknowledgment of mistakes. Leaders who own their missteps and act on them with sincerity build credibility and model accountability. Case examples, like Satya Nadella’s strategic redirection at Microsoft, highlight how vulnerability can serve as a leadership asset—not a liability.

The chapter then shifts to humility in action, emphasizing inclusive decision-making and shared success. Leaders are encouraged to shift from ego-driven authority to an “ecosystem” mindset—where insights come from all levels, and success is distributed across the team. Participants will see how this approach fosters stronger cohesion and long-term adaptability, with leaders like Jacinda Ardern providing a global benchmark.

Finally, humility is examined as a daily leadership habit. The chapter outlines actionable practices such as reflective self-awareness, generous credit-sharing, regular feedback loops, and empowering others to lead. These small, consistent behaviors embed humility into everyday leadership and signal a culture of integrity and continuous learning.

Throughout the chapter, participants will engage with real-world case studies, personal reflection prompts, and guided exercises designed to help them evaluate and expand their own humility as leaders. They’ll be challenged to confront ego-driven habits, model authenticity, and build inclusive environments where others can thrive.

By the end of the module, participants will understand humility not just as a personality trait, but as a strategic, relational, and ethical foundation for leadership. In a world where authority is no longer enough, humble leaders lead with credibility, connection, and the courage to grow. This chapter equips participants with the tools to cultivate that kind of leadership from the inside out.

Chapter 6: Cultural Integrity

This module explores cultural integrity—the alignment between an organization’s stated values and the behaviors, decisions, and systems that shape daily life. Culture, though often invisible, plays a defining role in how people work, interact, and respond to change. When that culture aligns with integrity—emphasizing honesty, fairness, and transparency—it becomes a powerful driver of trust, employee engagement, and long-term success.

Peter Drucker’s quote, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” is a central concept in this module. Even the most well-designed strategies will fail if they are not supported by the organization’s cultural norms. Culture determines whether change is embraced or resisted, whether collaboration flourishes or silos persist, and whether employees feel safe to innovate or fear making mistakes. Leaders must therefore align cultural conditions with strategic intentions, especially during periods of adaptive change.

Participants will examine signs of cultural misalignment, such as when organizations say they value transparency but operate in secrecy, or promote collaboration while rewarding individualism. These contradictions erode trust and credibility. In contrast, cultural integrity helps guide decisions and behaviors under pressure, reinforcing shared purpose and enabling ethical, effective responses to change.

Participants will examine signs of cultural misalignment, such as when organizations say they value transparency but operate in secrecy, or promote collaboration while rewarding individualism. These contradictions erode trust and credibility. In contrast, cultural integrity helps guide decisions and behaviors under pressure, reinforcing shared purpose and enabling ethical, effective responses to change.

The module provides practical tools for diagnosing cultural integrity. These include employee surveys, focus groups, 360-degree feedback, and audits of everyday practices—from promotion criteria to communication norms. Participants will also explore recognized frameworks like the Barrett Values Assessment and Denison Culture Model to benchmark alignment and track progress over time.

Importantly, cultural integrity is not about perfection—it’s about congruence. Leaders who acknowledge gaps between values and practice, and work openly to address them, demonstrate humility and credibility. Through intentional modeling, listening, and systems alignment, they shape cultures where integrity is not just a statement but a lived experience.

By the end of the module, participants will understand how to evaluate their organization’s cultural landscape, identify misalignments, and use strategic tools to foster a culture rooted in integrity. This cultural foundation becomes essential for leading adaptive change, building resilient teams, and earning the trust of both employees and stakeholders.

In today’s uncertain environments, integrity-driven culture is not just an ethical advantage—it’s a strategic imperative.

Chapter 7: Communicating Integrity

This chapter explores how communication becomes a cornerstone of leadership integrity—especially during times of uncertainty, organizational change, or adaptive challenge. It emphasizes that integrity isn’t only about what leaders do—it’s also about how they communicate: clearly, consistently, and with respect. Participants will learn how to align language with values, convey difficult truths with empathy, and reinforce trust through open and transparent dialogue.

The module begins by examining Communicating with Consistency, the foundation of credibility. When leaders consistently align their words with their actions and stated values, they create a sense of reliability and trust. Conversely, when there’s a gap—known as the “say-do gap”—employees grow skeptical, reducing engagement and morale. Leaders will explore how to keep messaging consistent across platforms, departments, and contexts while remaining adaptable during changing circumstances.

Next, the module addresses Navigating Difficult Conversations with Respect and Transparency. Participants will learn techniques to deliver challenging news—such as feedback, organizational shifts, or performance concerns—in ways that preserve dignity and trust. Through practical frameworks and examples, they’ll explore how to be honest without being harsh, and how to approach conversations with empathy, clarity, and accountability.

In Messaging During Uncertainty and Organizational Change, the focus shifts to the leadership imperative of timely, transparent communication. Participants will examine why silence or sugarcoating during change creates confusion and mistrust. They’ll explore strategies for anchoring messages in organizational purpose, addressing emotional responses, and maintaining communication momentum through regular updates and two-way channels.

The chapter also explores Building Psychological Safety Through Honest Communication, showing how trust flourishes when employees feel safe to speak up, share ideas, or admit mistakes. Leaders will learn how vulnerability, clarity, and respectful feedback loops help foster a culture where voices are heard and valued.

Throughout the module, participants engage with real-world case studies, interactive exercises, and communication simulations to apply their learning. By the end of the chapter, leaders will understand how integrity in communication reinforces organizational values, builds credibility, and enables adaptive success. They will leave with actionable tools to lead conversations that are not only informative—but inspiring, unifying, and grounded in ethical leadership.

Chapter 8: Leadership Integrity

This chapter focuses on the critical role leaders play in upholding and modeling organizational values. Integrity is not a passive leadership trait—it’s an active, visible practice that builds trust, drives accountability, and reinforces the credibility of both the leader and the organization. Participants will explore how integrity is expressed not only through formal statements or policies, but through the daily decisions, behaviors, and communication styles of leadership.

We begin by examining what it means to “walk the talk.” Leaders set the cultural tone by demonstrating values in action—whether through how they give feedback, manage conflicts, or make decisions under pressure. This alignment between values and behavior builds credibility. In contrast, when a leader’s actions contradict the values they promote, a damaging “integrity gap” emerges, eroding employee engagement and fueling cynicism.

The module also addresses leadership under pressure. Crises and moments of change are the ultimate tests of integrity. Leaders will reflect on how they respond during uncertainty—do they uphold fairness and transparency, or fall into shortcuts and avoidance? Real-world case studies will illustrate the long-term consequences of both approaches.

The module also addresses leadership under pressure. Crises and moments of change are the ultimate tests of integrity. Leaders will reflect on how they respond during uncertainty—do they uphold fairness and transparency, or fall into shortcuts and avoidance? Real-world case studies will illustrate the long-term consequences of both approaches.

To turn insight into action, the chapter guides participants through the creation of personal accountability plans—structured tools for self-assessment and behavioral alignment. Leaders will identify their core values, translate them into daily leadership commitments, and explore reflection methods and feedback loops to strengthen consistency.

By the end of the session, participants will:

• Understand how integrity shapes culture and trust.

• Identify behaviors that close or widen the integrity gap.

• Learn how to maintain ethical leadership during crises.

• Build a sustainable plan for personal accountability.

Ultimately, this chapter empowers leaders to embody the values they promote—not just in principle, but in practice. Integrity becomes more than an ideal; it becomes a leadership habit that defines tone, builds resilience, and ensures that values are lived at every level of the organization.

Chapter 9: Adaptive Integrity

In volatile and disruptive environments, leadership integrity becomes a critical stabilizer. This chapter explores the importance of upholding core values during times of uncertainty, when ethical standards are most vulnerable to compromise. Leaders are often required to make swift, high-stakes decisions during organizational change—be it market shifts, restructuring, or crisis situations. These moments can either erode trust or solidify it, depending on how transparently and ethically decisions are made.

Participants will examine the role of integrity as a compass that guides behavior when clarity is limited. Acting with honesty, consistency, and fairness during disruption helps reduce anxiety, strengthen psychological safety, and reinforce organizational culture. Case examples and reflective insights reveal how poor integrity during change can damage morale and credibility, while principled leadership builds resilience and trust.

The chapter highlights common integrity dilemmas that emerge during disruption, such as balancing transparency with confidentiality, navigating layoffs, avoiding favoritism, and aligning rapid change with long-standing values. It explores how these ethical tensions are rarely black and white—but require thoughtful consideration and courage.

To help leaders respond with integrity under pressure, the module introduces practical strategies for ethical decision-making. These include slowing down decision pace, applying a “values filter,” seeking diverse perspectives, and separating emotion from action. It also emphasizes the importance of documenting rationale and protecting space for dissenting voices—ensuring that ethical leadership is not just modeled, but also encouraged throughout the organization.

Interactive scenarios and discussion prompts give participants the opportunity to practice applying these tools in realistic, high-pressure contexts. They’ll explore how to maintain alignment between personal values, organizational mission, and stakeholder needs—even when outcomes are uncertain.

Ultimately, participants will leave with a deeper understanding that integrity is not just a leadership trait—it is an active discipline. It must be practiced intentionally, especially when stakes are high. Through this module, leaders will build the confidence and capacity to lead ethically, consistently, and transparently through any disruption—becoming anchors of trust and credibility in their organizations.

Chapter 10: Measuring Integrity

In this chapter, participants will explore how integrity can be measured as a practical, strategic element of organizational success—not just as a philosophical value. While integrity is often seen as cultural or personal, organizations that aim to operate ethically and adaptively must learn to evaluate how well their values are reflected in actual behavior, systems, and decisions.

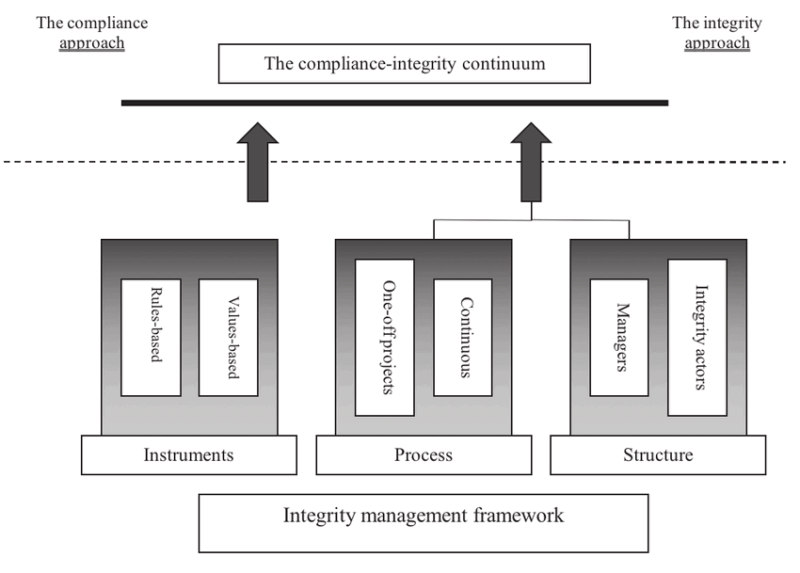

The session begins by introducing frameworks that help leaders assess integrity in structured and repeatable ways. These frameworks examine key dimensions such as leadership behavior, decision-making processes, employee experience, policy alignment, and communication culture. Leaders will explore established models like the Ethics Resource Center’s Ethics Framework and the Integrity Continuum, as well as customized tools that reflect their organization’s unique mission and values.

Participants will then learn how to define specific indicators and metrics that reflect values in action—such as transparency, fairness, and accountability. These indicators go beyond checklists, incorporating both quantitative data (e.g., ethics report submissions, survey responses) and qualitative insights (e.g., personal stories, behavioral observations). By translating abstract values into measurable components, organizations gain clarity on how integrity shows up—or falls short—across different levels.

Participants will then learn how to define specific indicators and metrics that reflect values in action—such as transparency, fairness, and accountability. These indicators go beyond checklists, incorporating both quantitative data (e.g., ethics report submissions, survey responses) and qualitative insights (e.g., personal stories, behavioral observations). By translating abstract values into measurable components, organizations gain clarity on how integrity shows up—or falls short—across different levels.

The module also explores how to build and implement custom integrity evaluation tools. Participants will design assessments that use plain language, mix anonymous feedback with targeted insights, and allow for adaptation across departments. Through this, they’ll ensure the tools reflect their organization’s language, priorities, and ethical expectations.

A major focus is placed on identifying integrity gaps—where stated values don’t align with daily practices. Through employee feedback, leadership reviews, and policy audits, participants will learn how to surface discrepancies, understand root causes, and take targeted actions to restore trust and alignment.

Finally, the chapter reinforces that integrity measurement must be ongoing. It’s not about assigning blame, but about reinforcing alignment between what an organization says and what it does. By embedding clear metrics and regular review processes, leaders can strengthen culture, build trust, and demonstrate that integrity is not aspirational—it’s operational, measurable, and essential to long-term success.

Participants will leave this module equipped to develop their own integrity evaluation plans, ready to lead with transparency, accountability, and authenticity across their organizations.

Chapter 11: Overcoming Barriers

This chapter explores one of the most critical, yet difficult, aspects of maintaining integrity in organizations: overcoming the real-world barriers that can derail ethical intentions. While many companies espouse integrity as a core value, executing it consistently across systems, behaviors, and decisions requires more than good intentions. It demands a clear understanding of what gets in the way—and the tools to address those challenges with strategy and courage.

Participants will begin by identifying common integrity barriers such as misaligned incentives, leadership inconsistency, fear of retaliation, and cultural contradictions. These barriers often arise not from malicious behavior but from organizational blind spots, systemic complexity, and pressure to prioritize short-term results over long-term values.

The module then addresses internal resistance, showing how skepticism, disengagement, or passive opposition can derail ethical initiatives. Leaders will learn how to recognize resistance early, engage in transparent dialogue, and co-create solutions with staff to foster buy-in and psychological safety.

The chapter also focuses on rebuilding trust after an integrity breach. Trust, once broken, requires clear accountability, open acknowledgment of harm, and systemic follow-through. Participants will learn how to take visible, consistent steps toward repair, while involving employees in restoring ethical culture.

Next, the chapter explores systemic issues that quietly undermine values—such as outdated reward structures or decision-making silos—and provides guidance on how to diagnose and redesign these systems. Practical strategies for aligning structures, policies, and resource allocation with core values are offered, reinforcing that integrity must be supported by operations, not just statements.

Throughout, participants are encouraged to see integrity as a dynamic practice, not a static goal. Integrity thrives when challenges are named and addressed honestly. It falters when leaders assume that declarations alone are enough.

The chapter concludes with the reminder that overcoming barriers to integrity is about persistence, not perfection. Through open communication, courageous leadership, and systemic alignment, organizations can repair trust, reduce resistance, and build cultures where doing the right thing is expected—and supported.

Leaders will leave this module equipped with diagnostic tools, case examples, and actionable strategies to address the ethical realities of their work environments. They’ll be better prepared to lead with clarity and compassion, even when integrity is tested.

Chapter 12: Sustainable Culture

The final chapter of this program focuses on how to sustain integrity as a long-term, living aspect of organizational culture—not simply a temporary initiative or top-down directive. In complex and evolving environments, integrity must be embedded into the strategy, systems, leadership, and daily practices of an organization. This chapter provides leaders with practical guidance on how to make ethical culture self-sustaining, visible, and deeply rooted across all levels.

Participants begin by exploring how to embed integrity into long-term organizational strategy. This includes aligning strategic goals with values, integrating ethical behavior into performance expectations, and ensuring that systems such as recruitment, leadership development, and communication are designed to reinforce—not contradict—organizational values.

The chapter then introduces reinforcement mechanisms like rituals, routines, and recognition. These are the daily behaviors and cultural cues that reinforce integrity in action—from values-based storytelling in meetings to public recognition of ethical decision-making. Leaders learn how these tools create shared habits and strengthen psychological safety over time.

Because cultures evolve, the module emphasizes monitoring and adaptation. Participants explore how to use data, feedback, and dialogue to track cultural alignment, identify drift, and adjust policies or practices to keep values relevant. Real-time listening and transparent leadership are key to making integrity a continuous, responsive force.

Because cultures evolve, the module emphasizes monitoring and adaptation. Participants explore how to use data, feedback, and dialogue to track cultural alignment, identify drift, and adjust policies or practices to keep values relevant. Real-time listening and transparent leadership are key to making integrity a continuous, responsive force.

Accountability systems are also addressed. Sustainable cultures require clear expectations, fair enforcement, and visible modeling—especially by leaders. The chapter highlights how to design systems where integrity is expected, supported, and rewarded, while unethical behavior is addressed swiftly and equitably.

Finally, the chapter culminates in a practical and personal exercise: developing a leader’s own integrity action plan. Participants reflect on their strengths and blind spots, set goals for modeling values-based leadership, and create an actionable roadmap they can take back to their teams. These individual plans reinforce the idea that cultural integrity is not abstract—it is lived, personalized, and made real through intentional choices.

Throughout the session, case studies and examples provide insight into how leading organizations sustain integrity across time, change, and complexity. By the end of the chapter, participants will leave with the mindset, tools, and plans needed to champion ethical leadership—not just as a program, but as a way of working, leading, and growing.

Curriculum

Adaptive Leadership – Workshop 4 – Organizational Integrity

- Organizational Integrity

- Establishing Security

- Honesty Communication

- Organizational Fairness

- Organizational Humility

- Cultural Integrity

- Communicating Integrity

- Leadership Integrity

- Adaptive Integrity

- Measuring Integrity

- Overcoming Barriers

- Sustainable Culture

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Adaptive Leadership corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast

As a guide, the Appleton Greene Adaptive Leadership corporate training program should take 12-18 months to complete, depending upon your availability and current commitments. The reason why there is such a variance in time estimates is because every student is an individual, with differing productivity levels and different commitments. These differentiations are then exaggerated by the fact that this is a distance-learning program, which incorporates the practical integration of academic theory as an as a part of the training program. Consequently all of the project studies are real, which means that important decisions and compromises need to be made. You will want to get things right and will need to be patient with your expectations in order to ensure that they are. We would always recommend that you are prudent with your own task and time forecasts, but you still need to develop them and have a clear indication of what are realistic expectations in your case. With reference to your time planning: consider the time that you can realistically dedicate towards study with the program every week; calculate how long it should take you to complete the program, using the guidelines featured here; then break the program down into logical modules and allocate a suitable proportion of time to each of them, these will be your milestones; you can create a time plan by using a spreadsheet on your computer, or a personal organizer such as MS Outlook, you could also use a financial forecasting software; break your time forecasts down into manageable chunks of time, the more specific you can be, the more productive and accurate your time management will be; finally, use formulas where possible to do your time calculations for you, because this will help later on when your forecasts need to change in line with actual performance. With reference to your task planning: refer to your list of tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve your program objectives; with reference to your time plan, calculate when each task should be implemented; remember that you are not estimating when your objectives will be achieved, but when you will need to focus upon implementing the corresponding tasks; you also need to ensure that each task is implemented in conjunction with the associated training modules which are relevant; then break each single task down into a list of specific to do’s, say approximately ten to do’s for each task and enter these into your study plan; once again you could use MS Outlook to incorporate both your time and task planning and this could constitute your study plan; you could also use a project management software like MS Project. You should now have a clear and realistic forecast detailing when you can expect to be able to do something about undertaking the tasks to achieve your program objectives.

Performance management

It is one thing to develop your study forecast, it is quite another to monitor your progress. Ultimately it is less important whether you achieve your original study forecast and more important that you update it so that it constantly remains realistic in line with your performance. As you begin to work through the program, you will begin to have more of an idea about your own personal performance and productivity levels as a distance-learner. Once you have completed your first study module, you should re-evaluate your study forecast for both time and tasks, so that they reflect your actual performance level achieved. In order to achieve this you must first time yourself while training by using an alarm clock. Set the alarm for hourly intervals and make a note of how far you have come within that time. You can then make a note of your actual performance on your study plan and then compare your performance against your forecast. Then consider the reasons that have contributed towards your performance level, whether they are positive or negative and make a considered adjustment to your future forecasts as a result. Given time, you should start achieving your forecasts regularly.

With reference to time management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual time taken in your study plan; consider your successes with time-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; consider your failures with time-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to time planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your time expectations. You need to be consistent with your time management, otherwise you will never complete your studies. This will either be because you are not contributing enough time to your studies, or you will become less efficient with the time that you do allocate to your studies. Remember, if you are not in control of your studies, they can just become yet another cause of stress for you.

With reference to your task management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual tasks that you have undertaken in your study plan; consider your successes with task-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case; take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; consider your failures with task-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future task planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to task planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your task expectations. You need to be consistent with your task management, otherwise you will never know whether you are achieving your program objectives or not.

Keeping in touch

You will have access to qualified and experienced professors and tutors who are responsible for providing tutorial support for your particular training program. So don’t be shy about letting them know how you are getting on. We keep electronic records of all tutorial support emails so that professors and tutors can review previous correspondence before considering an individual response. It also means that there is a record of all communications between you and your professors and tutors and this helps to avoid any unnecessary duplication, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation. If you have a problem relating to the program, share it with them via email. It is likely that they have come across the same problem before and are usually able to make helpful suggestions and steer you in the right direction. To learn more about when and how to use tutorial support, please refer to the Tutorial Support section of this student information guide. This will help you to ensure that you are making the most of tutorial support that is available to you and will ultimately contribute towards your success and enjoyment with your training program.

Work colleagues and family

You should certainly discuss your program study progress with your colleagues, friends and your family. Appleton Greene training programs are very practical. They require you to seek information from other people, to plan, develop and implement processes with other people and to achieve feedback from other people in relation to viability and productivity. You will therefore have plenty of opportunities to test your ideas and enlist the views of others. People tend to be sympathetic towards distance-learners, so don’t bottle it all up in yourself. Get out there and share it! It is also likely that your family and colleagues are going to benefit from your labors with the program, so they are likely to be much more interested in being involved than you might think. Be bold about delegating work to those who might benefit themselves. This is a great way to achieve understanding and commitment from people who you may later rely upon for process implementation. Share your experiences with your friends and family.

Making it relevant

The key to successful learning is to make it relevant to your own individual circumstances. At all times you should be trying to make bridges between the content of the program and your own situation. Whether you achieve this through quiet reflection or through interactive discussion with your colleagues, client partners or your family, remember that it is the most important and rewarding aspect of translating your studies into real self-improvement. You should be clear about how you want the program to benefit you. This involves setting clear study objectives in relation to the content of the course in terms of understanding, concepts, completing research or reviewing activities and relating the content of the modules to your own situation. Your objectives may understandably change as you work through the program, in which case you should enter the revised objectives on your study plan so that you have a permanent reminder of what you are trying to achieve, when and why.

Distance-learning check-list

Prepare your study environment, your study tools and rules.

Undertake detailed self-assessment in terms of your ability as a learner.

Create a format for your study plan.

Consider your study objectives and tasks.

Create a study forecast.

Assess your study performance.

Re-evaluate your study forecast.

Be consistent when managing your study plan.

Use your Appleton Greene Certified Learning Provider (CLP) for tutorial support.

Make sure you keep in touch with those around you.

Tutorial Support

Programs

Appleton Greene uses standard and bespoke corporate training programs as vessels to transfer business process improvement knowledge into the heart of our clients’ organizations. Each individual program focuses upon the implementation of a specific business process, which enables clients to easily quantify their return on investment. There are hundreds of established Appleton Greene corporate training products now available to clients within customer services, e-business, finance, globalization, human resources, information technology, legal, management, marketing and production. It does not matter whether a client’s employees are located within one office, or an unlimited number of international offices, we can still bring them together to learn and implement specific business processes collectively. Our approach to global localization enables us to provide clients with a truly international service with that all important personal touch. Appleton Greene corporate training programs can be provided virtually or locally and they are all unique in that they individually focus upon a specific business function. They are implemented over a sustainable period of time and professional support is consistently provided by qualified learning providers and specialist consultants.

Support available

You will have a designated Certified Learning Provider (CLP) and an Accredited Consultant and we encourage you to communicate with them as much as possible. In all cases tutorial support is provided online because we can then keep a record of all communications to ensure that tutorial support remains consistent. You would also be forwarding your work to the tutorial support unit for evaluation and assessment. You will receive individual feedback on all of the work that you undertake on a one-to-one basis, together with specific recommendations for anything that may need to be changed in order to achieve a pass with merit or a pass with distinction and you then have as many opportunities as you may need to re-submit project studies until they meet with the required standard. Consequently the only reason that you should really fail (CLP) is if you do not do the work. It makes no difference to us whether a student takes 12 months or 18 months to complete the program, what matters is that in all cases the same quality standard will have been achieved.

Support Process