Mastering Strategy – Workshop 1 (Strategy Matters)

The Appleton Greene Corporate Training Program (CTP) for Mastering Strategy is provided by Mr. Ward Certified Learning Provider (CLP). Program Specifications: Monthly cost USD$2,500.00; Monthly Workshops 6 hours; Monthly Support 4 hours; Program Duration 22 months; Program orders subject to ongoing availability.

If you would like to view the Client Information Hub (CIH) for this program, please Click Here

Learning Provider Profile

Chris Ward is a is a Certified Learning Provider (CLP) with Appleton Greene and a Certified Management Consultant, a professional consulting designation that is recognized in over 50 countries around the world. He has an MBA from the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto.

He has over 35 years of experience in consulting, coaching and line management. He specializes in strategic planning and execution, brand strategy, marketing strategy, and providing general business advice to senior executives. He has extensive experience in executive line management positions in retail, manufacturing, and professional services businesses. He is passionate about working with major corporations, owner-managed companies, and membership organizations to develop strategies for staking out and owning a defensible market position, and earning an unfair share of mind, market and wallet.

He has been directly responsible for the launch of three companies one of which grew through merger and acquisition to be a major player in its segment (electronic security for homes and businesses). He also founded and presided over the rapid growth of a successful custom publishing business that numbered among its clients some of North America’s most successful organizations.

Mr. Ward’s industry experience includes professional services, membership organizations, retail, manufacturing, and education. He has commercial experience in the United States and Canada and specifically in New York, Toronto, Dallas, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

His service skills include strategic planning, workshop and meeting facilitation, market research (including key informant interviews, online surveys, focus groups), and stakeholder communications for both for- and not-for-profit organizations.

He is the author of numerous articles and white papers including The Path to Extraordinary Results. This paper introduces a proven system for laser-focusing leaders and their teams on creating the future they want their business to own… and achieving results that are beyond the ordinary. He coauthored a paper entitled Leadership’s Pivotal Role in the Success & Failure of Essential Strategic Initiatives. This paper highlights lessons in vision, engagement, adaptability and operational excellence that provide leaders with a blueprint for profoundly shaping strategic outcomes.

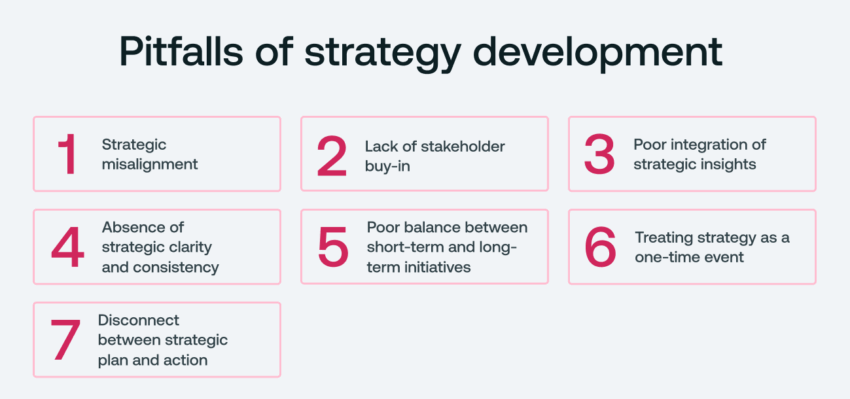

To enable clients and others to better understand the effectiveness of their current strategic plan and strategic planning process, Mr. Ward developed Your Strategic Number (YSN). YSN assesses the effectiveness of an organization’s existing strategy and strategic planning process by measuring performance in seven key areas. The goal is to uncover issues that could limit the organization’s ability to achieve its longer-term goals and to help decision makers focus their planning on mission-critical areas.

As Entrepreneur In Residence at the Ivey Business School at Western University, Mr. Ward has coached and mentored teams of students engaged in consulting projects with private and public sector organizations. He was a chair and member of The Executive Committee (Vistage), an international network of CEOs focused on improving their leadership abilities and achieving their professional and personal goals. Currently, he is member of the board of directors of a company that invests in uncompromised Good Delivery gold, silver and platinum bullion bars and coins.

MOST Analysis

Mission Statement

Part 1 Month 1 Strategy Matters – In this module, we’ll provide an overview of the Mastering Strategy training program and explore the ways in which strategy benefits organizations and the people who lead them. We’ll review a number of decision-making techniques used throughout the program as well as different methods of reaching consensus on key issues. Using real-life examples, we’ll demonstrate how leaders who understand strategy are better able to anticipate and deal with major business challenges, change direction as circumstances dictate, avoid knee-jerk reactions to disruption, and communicate a vision that their teams buy into and rally around. We’ll showcase several companies in which attention to strategy had a sizable impact on results, including a mid-sized manufacturing firm that transformed its market position by aligning every level of management around a well-defined strategic plan. Using a case study that illustrates the importance of being strategic and a simulation exercise in which you’ll be challenged by a variety of factors including a volatile market, you’ll discover how a firm understanding of strategy and the ability to see the big picture combine to make a significant difference to an organization’s overall success. On a personal level, you’ll see how being strategic differentiates you from others and positions you get ahead in your business and personal lives.

Objectives

01. What Mastering Strategy Is All About: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

02. Thinking Strategically: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

03. Benefits of a Strategic Approach: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

04. Strategic Enablers: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

05. The Cost of Bad Strategy: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

06. Case Study – Strategy in Action: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

07. Strategic Leadership in Practice: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. 1 Month

08. Core Strategic Tools Overview: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

09. Aligning Strategy with Vision and Values: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

10. Strategy Simulation Exercise – Market Disruption: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

11. Getting It Done: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

12. Your Personal Strategic Edge: departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development. Time Allocated: 1 Month

Strategies

01. What Mastering Strategy Is All About: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

02. Thinking Strategically: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

03. Benefits of a Strategic Approach: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

04. Strategic Enablers: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

05. The Cost of Bad Strategy: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

06. Case Study – Strategy in Action: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

07. Strategic Leadership in Practice: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

08. Core Strategic Tools Overview: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

09. Aligning Strategy with Vision and Values: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

10. Strategy Simulation Exercise – Market Disruption: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

11. Getting It Done: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

12. Your Personal Strategic Edge: Each individual department head to undertake departmental SWOT analysis; strategy research & development.

Tasks

01. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse What Mastering Strategy Is All About.

02. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Thinking Strategically.

03. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Benefits of a Strategic Approach.

04. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Strategic Enablers.

05. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze The Cost of Bad Strategy.

06. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Case Study – Strategy in Action.

07. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Strategic Leadership in Practice.

08. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Core Strategic Tools Overview.

09. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyze Aligning Strategy with Vision and Values.

10. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Strategy Simulation Exercise – Market Disruption.

11. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Getting It Done.

12. Create a task on your calendar, to be completed within the next month, to analyse Your Personal Strategic Edge.

Introduction

In today’s complex and competitive environment, strategy serves as both a compass and a framework—guiding organizations through uncertainty, aligning teams behind shared objectives, and helping leaders make thoughtful, impactful decisions. The term “strategy” often conjures images of long meetings and PowerPoint decks, but in its most vital form, strategy is about clarity, direction, and action. It defines where an organization is headed, how it plans to get there, and what choices it will make along the way.

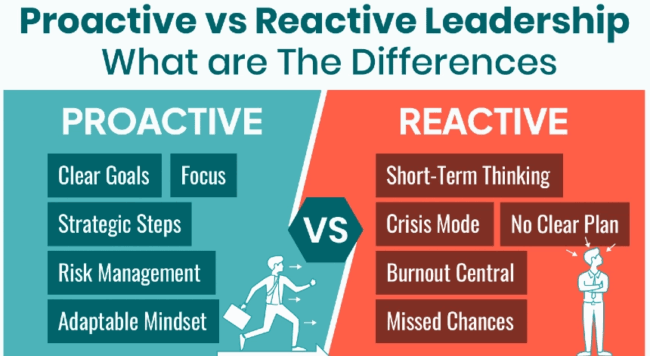

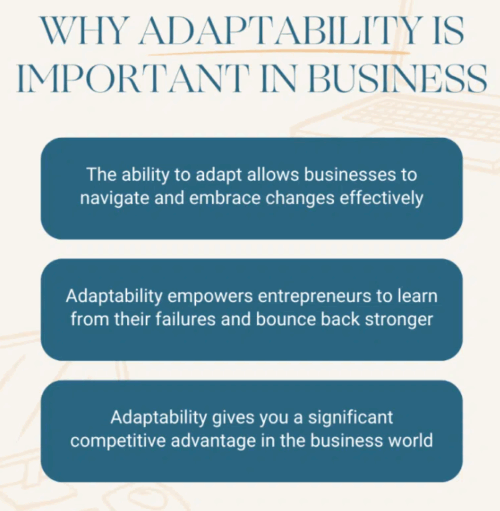

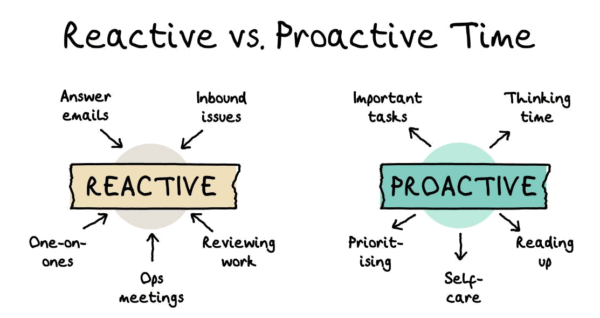

Strategy matters because it empowers organizations to move from reactionary to intentional behavior. Rather than simply responding to changes in the marketplace or internal disruptions, strategically minded organizations proactively shape their futures. They assess where they are, identify where they want to be, and determine how to bridge that gap. This clarity enables better use of resources, more confident decision-making, and greater adaptability.

Moreover, strategy is not limited to corporate headquarters or executive boardrooms. It must be understood and embraced at all levels of the organization. Managers, team leads, and individual contributors each play a role in executing strategy and understanding its significance allows them to better align their actions to broader business goals.

The Mastering Strategy program begins with this foundational principle: strategy is essential not only for achieving organizational success but also for building capable and forward-thinking leaders. This module explores the concept of strategy from the ground up, offering tools, frameworks, and real-world perspectives that demonstrate why strategic thinking is a differentiator in both professional and personal contexts.

Strategic Thinking as a Leadership Advantage

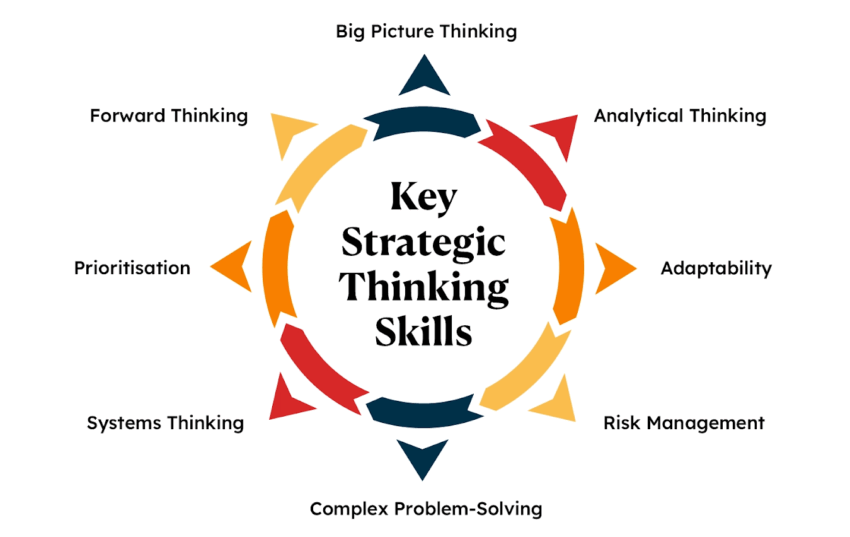

Strategic thinking is a defining trait of effective leadership. It elevates decision-making beyond immediate operational concerns and enables leaders to connect daily actions to long-term ambitions. While some leaders are skilled at managing the present—focusing on execution, performance targets, and short-term gains—those who think strategically take a broader, more dynamic view. They do not merely respond to what is happening; they actively anticipate what might happen next.

At its core, strategic thinking involves disciplined reflection and foresight. It requires leaders to step outside of day-to-day pressures and examine the bigger picture—asking questions like: What trends are emerging in our industry? What assumptions are we making about the future? What are our blind spots? By seeking answers to these types of questions, strategic leaders develop a clearer understanding of the environment in which they operate and the variables that could shape future outcomes.

This mindset influences how leaders allocate limited resources. Rather than spreading efforts thinly across many initiatives, strategic leaders prioritize areas with the greatest potential return. They are more likely to invest in innovation, develop key talent, or build infrastructure that supports long-term scalability. They think in terms of systems—understanding how one decision reverberates across departments, customer touchpoints, supply chains, and financial outcomes.

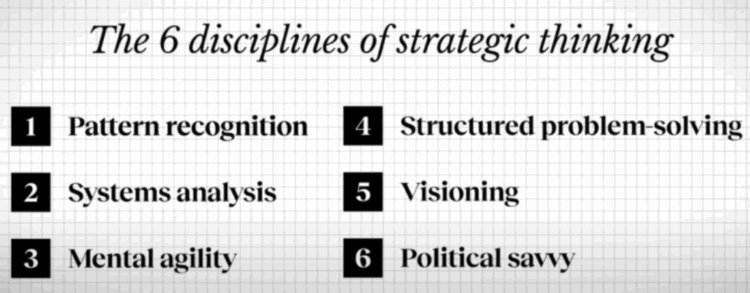

Another critical element of strategic thinking is pattern recognition. Leaders who excel in strategy are constantly scanning for signals—both internal and external. They detect weak signals before they become disruptive forces, identify opportunities that others overlook, and connect seemingly unrelated events into actionable insights. This ability to spot patterns and connect dots gives them a competitive edge, particularly in environments marked by rapid change.

When disruption does occur—whether from technology shifts, economic downturns, or competitive threats—strategic thinkers maintain composure. Their strength lies in pausing to assess the full context before choosing a path forward. They do not jump into action blindly or default to what worked in the past. Instead, they consult data, test assumptions, seek diverse perspectives, and carefully weigh the trade-offs of each option. This measured approach fosters better risk management and leads to more resilient decision-making.

Agility is also a hallmark of strategic leaders. While they commit to a direction, they remain flexible in how they pursue it. They treat strategy as a living framework rather than a rigid plan. If external conditions shift or new insights emerge, they are prepared to pivot without losing sight of the overarching goals. This blend of clarity and adaptability allows them to course-correct without undermining confidence or cohesion within the organization.

Critically, strategic thinking is not the sole domain of C-suite executives or boardrooms. It can and should be developed at every level of the organization. Managers, team leads, and frontline staff all benefit from cultivating a strategic lens. Employees who understand how their work contributes to the organization’s long-term strategy are more engaged, more innovative, and more likely to contribute meaningfully to business success. They become proactive problem-solvers rather than reactive task-performers.

Furthermore, strategic thinking builds influence and visibility. Individuals who bring forward long-term perspectives, who offer data-informed suggestions, and who demonstrate an understanding of the broader business environment are often trusted with greater responsibility. On a personal level, developing a strategic mindset can be a key differentiator—positioning individuals for leadership roles, cross-functional projects, and career advancement.

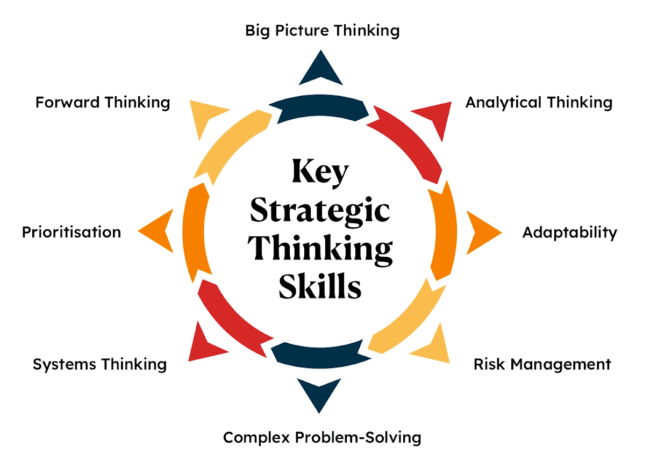

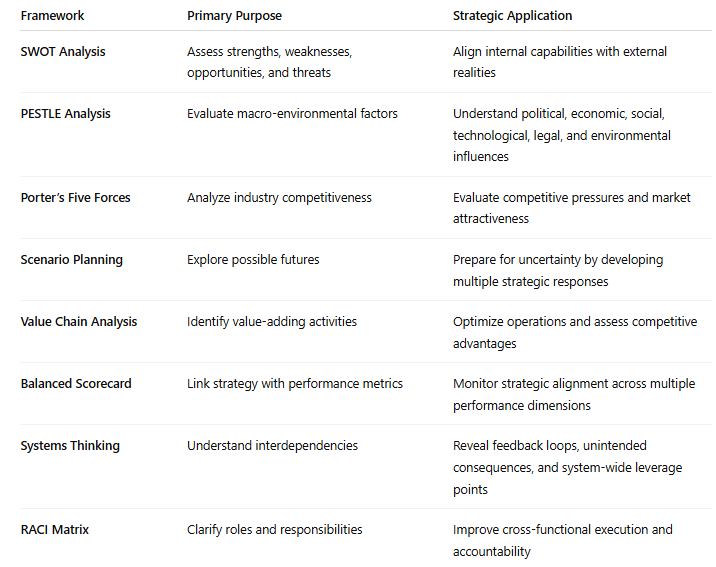

In practice, strategic thinking involves both mindset and method. It combines curiosity, analysis, creativity, and discipline. This course introduces several key frameworks designed to support the development of strategic capabilities:

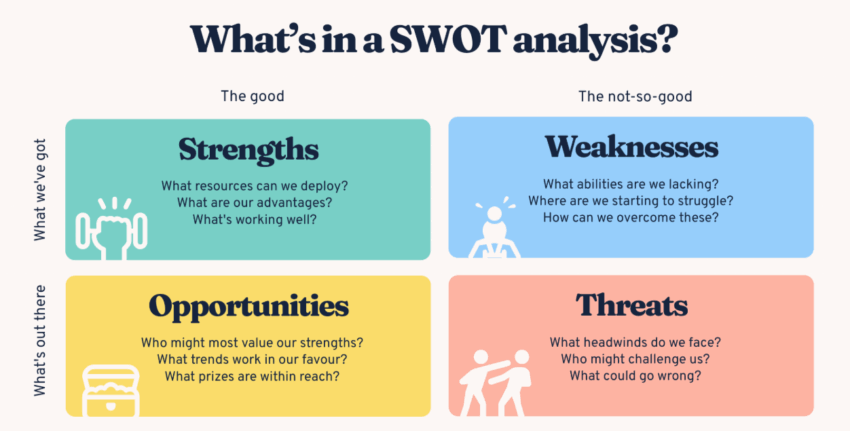

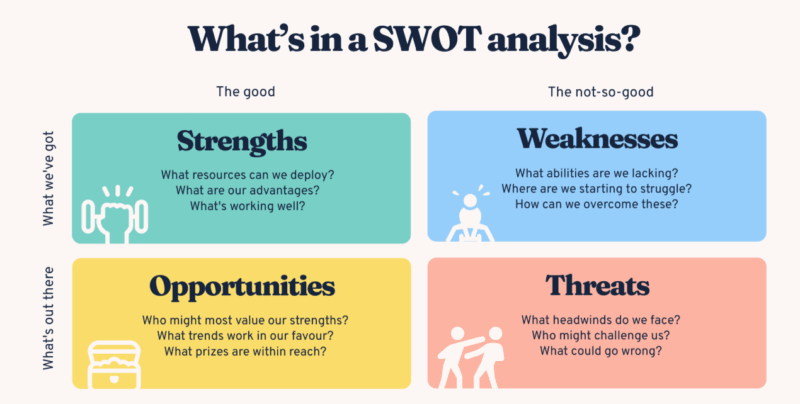

• SWOT Analysis helps identify internal strengths and weaknesses alongside external opportunities and threats, providing a structured view of the organization’s strategic position.

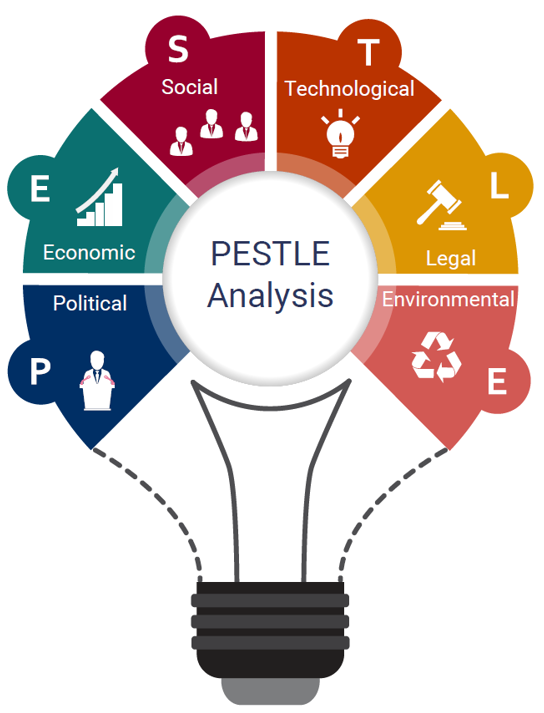

• PESTLE Analysis examines the broader macro-environmental factors—political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental—that influence long-term planning.

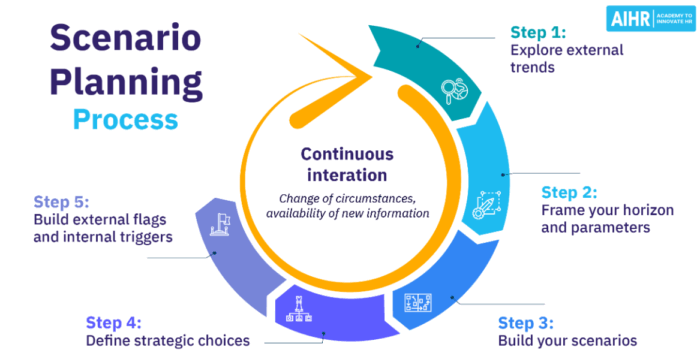

• Scenario Planning equips leaders to explore multiple plausible futures, preparing for a range of possibilities rather than relying on a single forecast.

• Systems Thinking enables a holistic view of how different elements interact within an organization, emphasizing cause-and-effect relationships and feedback loops.

These tools are not meant to replace judgment but to sharpen it. They provide scaffolding for deeper insight and allow leaders to approach complex challenges with confidence and clarity. By applying these methods throughout the course, participants will learn to break down complexity, surface hidden variables, and consider both immediate and downstream implications of their decisions.

Ultimately, strategic thinking is what allows leaders to connect today’s actions with tomorrow’s vision. It is the difference between managing a business and shaping its future. In a world where change is constant and uncertainty is the norm, this capability is not just valuable—it is essential.

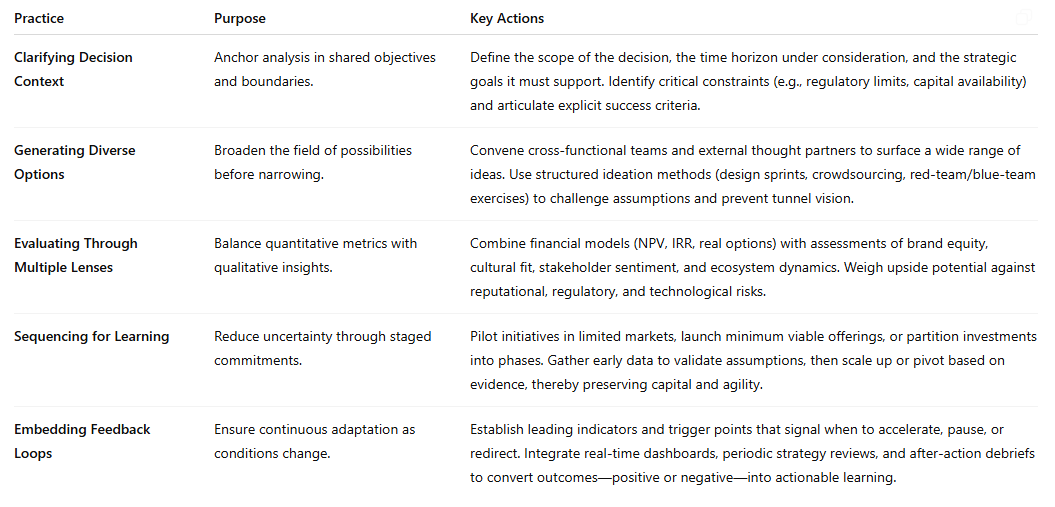

Decision-Making and Consensus Building

Effective strategy is inseparable from the ability to make sound decisions. Strategic decision-making is not simply about choosing the most obvious option or following standard procedures—it is about navigating complexity, assessing risk, balancing competing interests, and committing to a direction with confidence, even when uncertainty is high. The most consequential decisions often present no clear-cut answers. Instead, they demand judgment, foresight, and a structured approach that considers both tangible and intangible factors.

In a business landscape characterized by constant change and limited visibility, leaders are frequently required to make decisions with incomplete information. These decisions may involve trade-offs between growth and stability, innovation and cost, or long-term investments versus short-term performance. The quality of these choices can determine whether an organization adapts and thrives—or stagnates and declines.

Strategic decision-making requires both rational analysis and human insight. While data plays a critical role in informing decisions, it must be interpreted within context. Numbers alone rarely provide all the answers. Leaders must evaluate not only what the data says, but what it means—and what might be missing from the picture. The best decisions integrate logic with experience, analysis with intuition, and stakeholder input with executive vision.

This module introduces several structured decision-making models designed to help reduce ambiguity, limit cognitive biases, and improve the overall quality of strategic choices:

• Decision Trees allow leaders to map out options visually, assess possible outcomes, and calculate the expected value of each path. This helps clarify the sequence and consequences of choices, especially in multi-step decisions.

• Cost-Benefit Analysis evaluates the relative financial and non-financial gains and costs of different courses of action, making it easier to compare alternatives objectively.

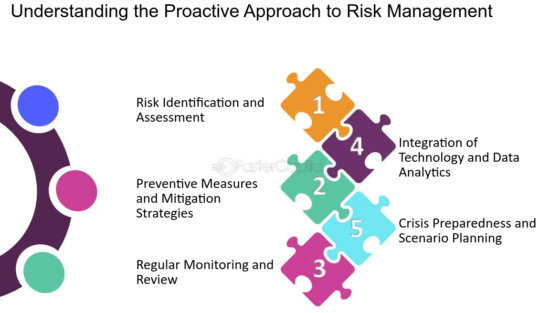

• Risk-Impact Matrices provide a systematic way to categorize potential risks based on their probability and impact, helping leaders identify where to focus attention and resources.

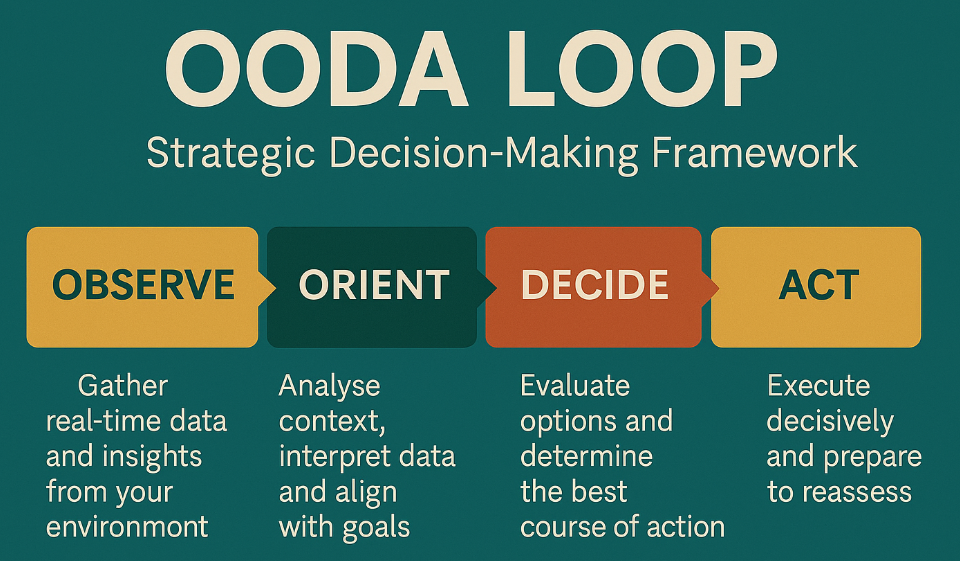

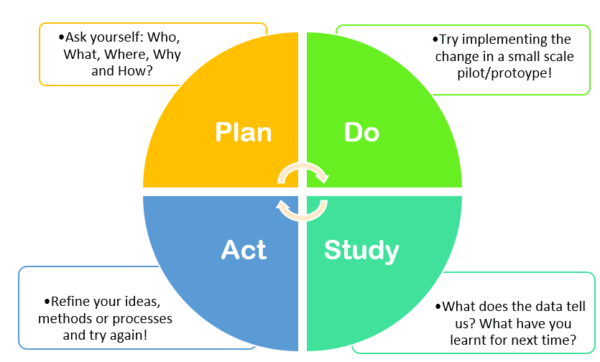

• The OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) supports rapid decision-making in dynamic environments by emphasizing continuous learning and adaptability through a recurring feedback loop.

By using these tools, leaders and teams can bring clarity to complex issues, challenge assumptions, and mitigate the influence of personal bias or groupthink. They create a shared language for decision-making and ensure that strategic choices are grounded in logic and evidence rather than gut instinct alone.

However, decision-making in an organizational context rarely happens in isolation. Major strategic decisions often involve multiple stakeholders across different departments, each with their own perspectives, incentives, and concerns. For a strategy to succeed, it must be embraced—not just endorsed—by those responsible for implementing it. This is where consensus building becomes critical.

Consensus building is the art of generating shared commitment to a decision, even when not everyone agrees on every detail. It is not about achieving unanimous agreement; rather, it is about fostering a collective willingness to support and execute a chosen course of action. When done effectively, consensus enhances buy-in, improves coordination, and reduces resistance during implementation.

Building consensus requires a specific set of leadership skills:

• Emotional intelligence to understand and manage the dynamics of interpersonal relationships, recognize resistance, and respond to the emotional undercurrents of strategic conversations.

• Clear communication to ensure that all participants understand the rationale behind each option, the criteria for evaluation, and the implications of various choices.

• Facilitation ability to create space for diverse viewpoints, resolve conflicting opinions, and guide groups toward constructive outcomes.

Leaders must also be comfortable with ambiguity. There will be times when the data points in one direction, but collective wisdom suggests another. In these cases, leaders must weigh evidence against judgment, recognizing that the best path may not always be the most immediately obvious one. In high-stakes decisions, leaders often operate in the “gray zone”—where multiple valid perspectives exist, and trade-offs are inevitable.

To support this aspect of leadership, the course introduces consensus-building frameworks that encourage inclusivity, structure, and transparency:

• The Delphi Method, which gathers and refines expert opinion through multiple rounds of anonymous input and feedback, helping to reduce the influence of dominant personalities and encourage diverse insights.

• The Nominal Group Technique, a structured process that balances individual idea generation with group evaluation, allowing quieter voices to be heard and creating a more democratic decision-making environment.

• Participatory Planning, which brings key stakeholders into the process from the beginning, fostering a sense of ownership and reducing resistance to outcomes by making everyone part of the solution.

Each of these techniques promotes collaborative decision-making while maintaining strategic discipline. They help avoid the pitfalls of either autocratic control (where decisions are made without input and fail to gain traction) or endless deliberation (where no decision ever gets made).

In today’s environment, where change is rapid, resources are limited, and accountability is high, the ability to make well-reasoned decisions and build collective support behind them is a powerful differentiator. Organizations that can consistently align their people around bold, yet thoughtful, strategic choices are better positioned to adapt, compete and lead.

Navigating Challenges Through Strategy

Every organization, regardless of size or sector, will face challenges—some internal, such as restructuring or talent shortages, and others external, like market disruptions, regulatory shifts, or economic downturns. What sets resilient organizations apart is not the absence of difficulties, but the presence of a strategic mindset that allows them to respond with purpose rather than panic.

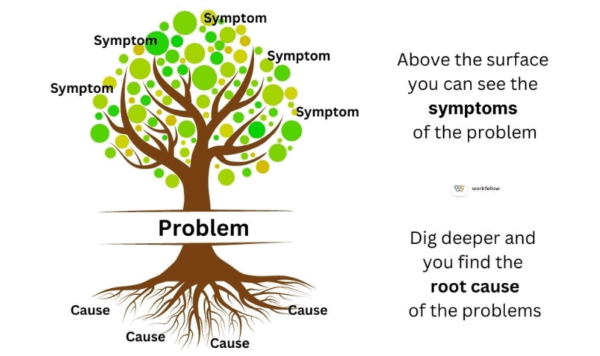

Strategy provides a structured way to understand challenges in their full context. Rather than reacting impulsively, strategic leaders take a step back to examine the broader environment, identify root causes, and assess potential ripple effects of each decision. This kind of thinking reduces the likelihood of short-sighted actions that fix one issue but create others. It also enables organizations to stay grounded in their long-term goals, even in the face of uncertainty.

For example, during times of financial strain, some companies resort to blanket cost-cutting measures that may erode employee morale or compromise innovation. Strategic organizations, by contrast, make targeted decisions—investing in areas that will yield the greatest long-term return, such as customer retention, operational improvements, or digital transformation. In doing so, they protect their core value proposition and preserve future competitiveness.

To support this approach, the module introduces practical tools for diagnosing and addressing complex challenges. These include the Five Whys technique for identifying root causes, the McKinsey 7S model for evaluating organizational alignment, and the Theory of Constraints for finding and resolving bottlenecks. Participants will also explore risk-assessment tools and learn how to develop contingency plans that improve agility and readiness.

Ultimately, strategy acts as a buffer in uncertain times. It helps leaders pause, assess, and decide based on a clear understanding of their environment and priorities. With a flexible but focused strategic framework in place, even disruptive events can be transformed into opportunities for renewal, innovation, and growth.

Vision, Alignment, and Execution

A compelling vision is the north star of any successful strategy. It crystallises why the organisation exists, where it is headed, and how it intends to win. More than a slogan, an effective vision is concise enough to remember, vivid enough to imagine, and ambitious enough to stretch current capabilities. When leaders articulate such a vision—rooted in purpose and reinforced by data—it sparks intrinsic motivation, guides resource allocation, and anchors decision-making during turbulence.

Yet inspiration alone is insufficient; the vision must migrate from slides to shop floor. Alignment is the bridge. In practice, alignment means translating high-level aspirations into concrete, tiered objectives that every business unit, team, and individual can own. Three principles underpin effective alignment:

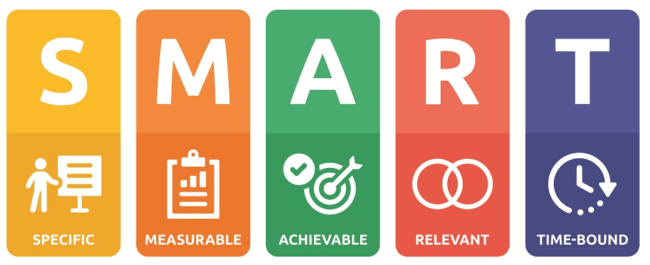

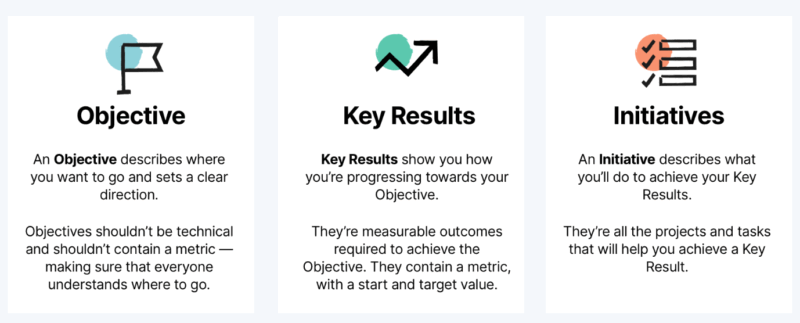

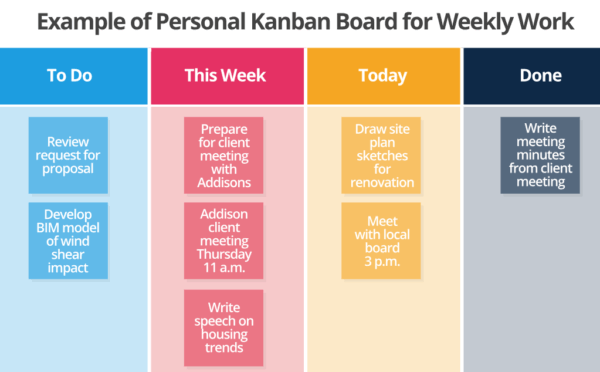

1. Strategic Cascading: Senior leaders first convert the vision into 3- to 5-year strategic priorities. These in turn cascade to annual objectives (e.g., OKRs or SMART goals) that departments refine into quarterly targets and weekly tasks.

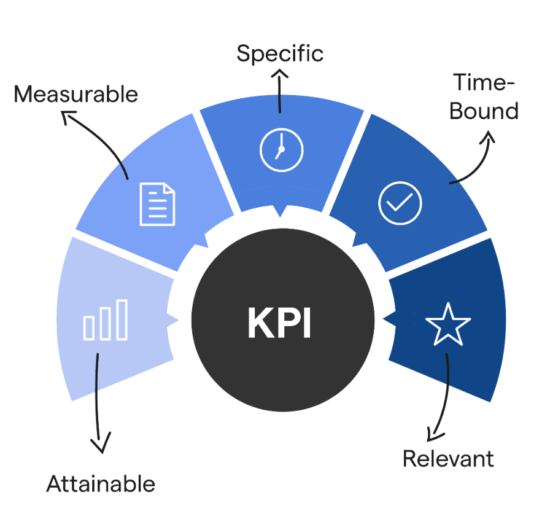

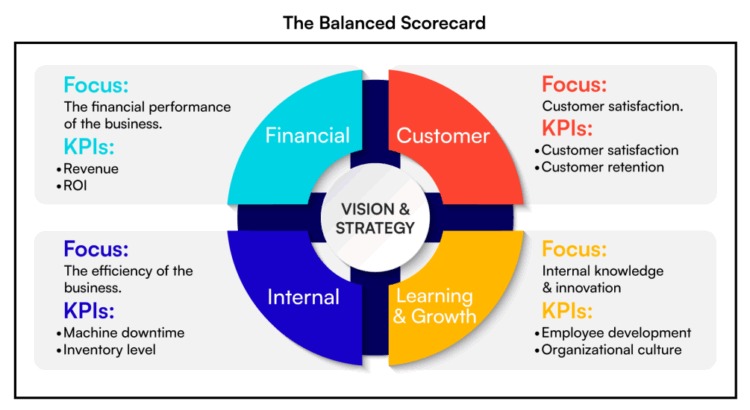

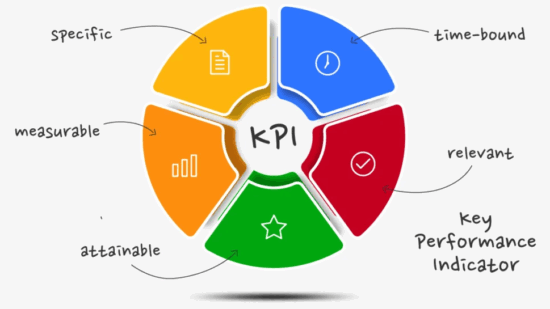

2. Shared Metrics: Balanced scorecards or KPI dashboards ensure that each level tracks both leading (predictive) and lagging (outcome) indicators. Common measures reduce siloed optimisation and keep cross-functional teams rowing in the same direction.

3. Governance and Dialogue: Regular review cadences—monthly business reviews, quarterly strategy sprints, and semi-annual off-sites—create forums where leaders test assumptions, surface interdependencies, and recalibrate when external signals shift.

Even with alignment, many strategies unravel during execution. Execution is the disciplined conversion of intent into measurable results. Common pitfalls include too many priorities, unclear ownership, resource bottlenecks, and weak feedback loops. High-execution organisations counter these hazards through four levers:

• Focus & Sequencing: Ruthlessly limiting major initiatives and mapping their critical-path dependencies prevents teams from overcommitting and spreading talent too thin.

• Resource Fluidity: Budgets, talent, and technology are continually reallocated to initiatives that demonstrate traction, using stage-gate or portfolio-management techniques.

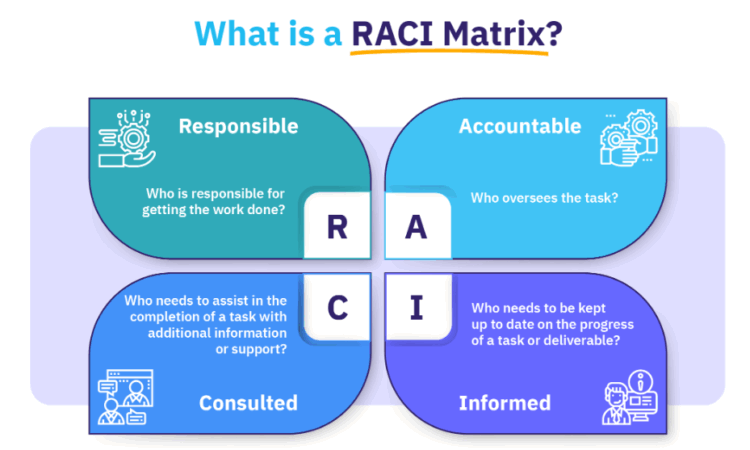

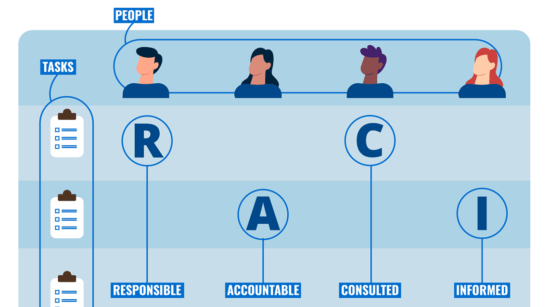

• Transparent Accountability: RACI matrices, performance contracts, and digital project boards clarify “who owns what by when,” leaving little room for ambiguity.

• Learning Rhythms: Weekly stand-ups, after-action reviews, and real-time analytics create short feedback cycles that flag risks early and celebrate quick wins, reinforcing momentum.

Leadership communication acts as connective tissue across vision, alignment, and execution. Storytelling, town-hall Q&As, and two-way digital platforms keep the vision alive, cascade context behind key decisions, and surface ground-level insights. Skilled communicators tailor their message to different stakeholder groups—translating strategy into customer value for frontline staff, risk-reward trade-offs for finance teams, and growth narratives for investors.

Vision, alignment, and execution function as a strategic triad. Vision charts the destination, alignment ensures every oar stroke propels the same boat, and execution converts collective effort into measurable progress. Mastering all three transforms strategy from an annual planning ritual into a living system that continually learns, adapts, and delivers.

Case Study: LEGO Group – The Classic Turnaround

Facing near bankruptcy in the early 2000s, LEGO was burdened by over-diversification—venturing into theme parks, video games, and unprofitable toy lines. In 2003, under new leadership from CEO Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, LEGO re-centered on its core brick-building business. The company:

• Streamlined operations by cutting SKUs, reducing workforce, and divesting non-core assets like Legoland parks

• Refocused innovation on product lines that reinforced the “system of play” philosophy, ensuring designs were both creative and commercially viable

• Rebuilt organization around disciplined processes, agility, and governance, and engaged consumers via platforms like Cuusoo

By 2005, LEGO returned to profitability, and by 2015 it had become the world’s largest toy manufacturer by revenue.

Ongoing success continues—LEGO achieved a 13 % revenue increase in H1 2024, demonstrating resilience even in inflationary contexts by expanding appeal to “kidults,” launching LEGO Icons sets, films, and digital partnerships.

Key Lessons:

• A sharp focus on core strengths restores purpose and integrity.

• Cost discipline must be paired with selective innovation.

• Consumer co creation and agile processes are powerful catalysts for sustained success.

Case Study: Strategic Vision and Agility in Crisis – Starbucks’ Reinvention

In the mid-2000s, Starbucks experienced a decline in customer traffic and brand loyalty. Rapid expansion had diluted the customer experience, and the company faced criticism for losing its original charm. Financial performance was underwhelming, and shareholder confidence was eroding.

Howard Schultz, Starbucks’ former CEO, returned to lead the company and implemented a bold strategic reinvention. His first step was to close over 7,000 stores for a day to retrain baristas on the art of coffee making—signaling a return to core values. Schultz also commissioned a strategic review, which led to a renewed focus on quality, customer connection, and digital innovation.

New initiatives included the introduction of mobile ordering, loyalty programs, and enhanced in-store experiences. Strategic partnerships were formed with music providers, payment platforms, and local communities. Importantly, the company prioritized agility—rapidly piloting new concepts and gathering real-time customer feedback.

Within three years, Starbucks saw a resurgence in brand strength, restored profitability, and regained its position as a global leader in premium coffee. The turnaround demonstrated the power of combining strategic clarity with cultural alignment and adaptability.

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: What Mastering Strategy Is All About

Strategy is often misunderstood—seen either as a set of lofty goals disconnected from day-to-day operations or as an overly complex exercise reserved for academics and consultants. In reality, effective strategy strikes a balance between clarity and depth. It requires a broad understanding of the organization’s context, a firm grasp of its priorities, and a structured path toward long-term success.

This first part of the course introduces the foundational ideas that underpin the entire Mastering Strategy program. It presents strategy as both an intellectual process and a practical tool—grounded in real-world business pressures but informed by thoughtful planning and foresight. It highlights how strategic thinking involves more than choosing between options; it is about recognizing patterns, aligning decisions with future outcomes, and maintaining focus in the face of complexity and change.

The content outlines key themes that will be explored throughout the course, including decision-making, alignment, execution, and the value of strategic adaptability. It emphasizes the importance of developing a strategy that not only reflects current market conditions and internal capabilities but also positions the organization to thrive in future scenarios.

Participants will examine what it means to think and lead strategically, with particular focus on how to translate vision into actionable goals. The section challenges oversimplified views that reduce strategy to a quick decision or a single annual planning exercise. At the same time, it cuts through the noise that can make strategy appear inaccessible or overly theoretical.

To support engagement and reflection, this part of the course includes a brief quiz designed to surface participants’ initial assumptions and awareness around strategic planning. The exercise encourages self-assessment and sets the stage for deeper learning as the course progresses.

Overall, this manual lays the groundwork for a practical, experience-driven approach to mastering strategy. It introduces core principles and recurring themes that will be developed in greater detail in the sections that follow, offering a clear and structured foundation for strategic thinking and implementation.

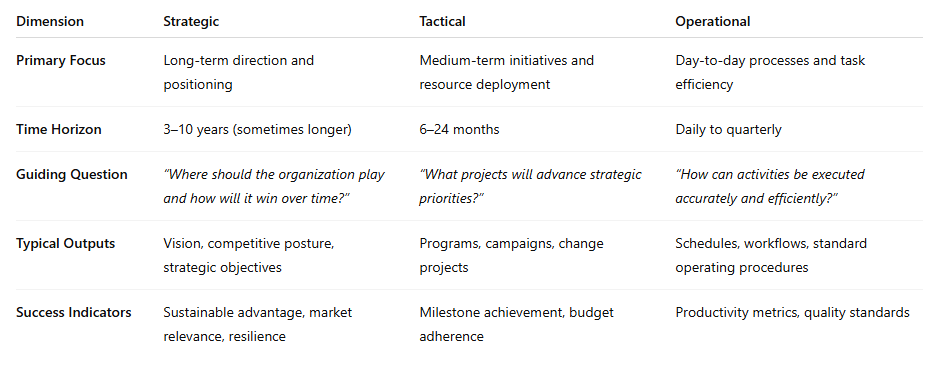

Chapter 2: Thinking Strategically

Strategic thinking is a distinct and essential skill that shapes how organizations navigate uncertainty and pursue long-term goals. Unlike tactical or operational thinking, which tends to focus on immediate tasks and short-term outcomes, strategic thinking takes a broader view. It considers context, anticipates future trends, and connects today’s decisions to tomorrow’s opportunities and risks.

This part of the course explores the characteristics and discipline of thinking strategically. It examines how effective strategic thinkers identify patterns, challenge assumptions, and make sense of complex, often ambiguous information. It also highlights the importance of systems thinking—understanding how various parts of the organization interact and how decisions made in one area affect outcomes in another.

The manual will distinguish strategic thinking from routine planning or reactive problem-solving. It highlights the value of long-term orientation, scenario analysis, and purposeful reflection. It will also introduce key tools and frameworks that support strategic thought, including environmental scanning, risk mapping, and goal alignment.

By understanding the mindset and methods associated with strategic thinking, organizations are better equipped to make resilient choices. Whether responding to disruption or setting a course for innovation, strategic thinkers offer insight that helps guide teams through uncertainty while staying focused on the big picture.

This section builds on the program’s introduction by emphasizing that strategy is not just a formal process—it is a way of seeing, interpreting, and responding to the world. Through this lens, strategic thinking becomes a practical leadership capability with real impact on decision-making, alignment, and long-term success.

Chapter 3: Benefits of a Strategic Approach

Adopting a strategic approach offers both immediate and lasting value to organizations and individuals alike. It creates a foundation for proactive decision-making, focused execution, and long-term resilience. When strategy becomes part of the organizational mindset—not just a once-a-year planning exercise—it begins to shape culture, guide priorities, and enhance overall performance.

This section explores the wide-ranging benefits of strategic thinking and planning. On a practical level, a well-developed strategy helps clarify direction, align resources, and coordinate cross-functional efforts. It provides a framework for setting priorities, managing risk, and measuring progress. By embedding strategy into everyday operations, teams operate with greater focus and consistency, reducing wasted effort and increasing productivity.

The intangible benefits are equally significant. A shared strategic vision fosters unity and motivation across departments and leadership levels. It helps build confidence during periods of uncertainty, offering a clear sense of purpose and direction. Individuals who operate with a strategic mindset are more likely to identify opportunities, influence others effectively, and contribute to sustainable growth.

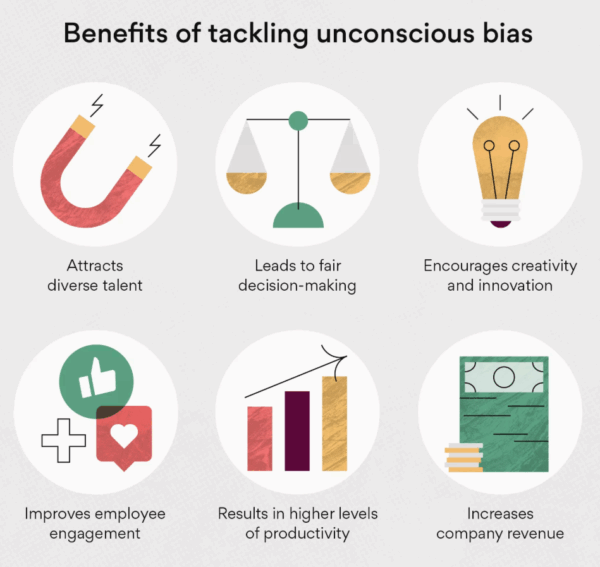

This part of the course also explores the role of collective ownership in strategy development. Broad support for a strategic plan improves buy-in and accountability, making implementation more effective. When stakeholders feel heard and involved, they are more committed to shared outcomes and more responsive to changing circumstances.

Additionally, the content reflects on how strategy can elevate leadership. Leaders who consistently apply a strategic lens tend to communicate more clearly, adapt more effectively, and build stronger teams. These traits not only benefit organizational performance but also support individual career development and influence.

By highlighting both the tangible outcomes and the cultural value of a strategic approach, this section underscores the broader purpose of strategy: to unify, guide, and enable individuals and organizations to thrive in dynamic environments.

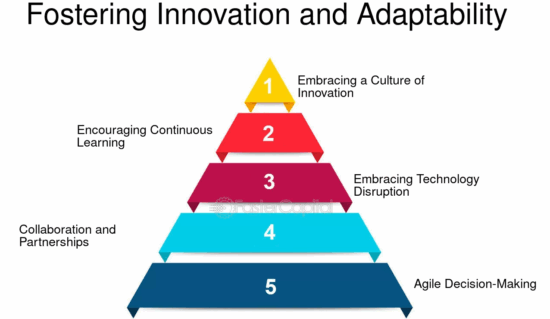

Chapter 4: Strategic Enablers

The success of any strategic planning effort depends not only on having a clear vision and solid objectives but also on recognizing and managing the factors that can enable—or derail—execution. These factors, often referred to as strategic enablers and disruptors, play a critical role in shaping the outcome of strategic initiatives.

This part of the course focuses on identifying both internal and external elements that influence the effectiveness of strategic plans. Strategic enablers are the systems, structures, people, and processes that support alignment, execution, and adaptability. These may include leadership commitment, cross-functional collaboration, access to accurate data, organizational culture, and the ability to learn and adjust in real time.

Equally important is the identification of potential disruptors—factors that can undermine strategic progress if not addressed early. These might include misaligned incentives, resource constraints, poor communication, rigid hierarchies, or shifting market conditions. Left unchecked, such disruptors can stall momentum, create confusion, and weaken confidence in the overall strategy.

This section explores practical methods for evaluating these enabling and limiting factors during the planning phase. Tools such as readiness assessments, risk impact matrices, and stakeholder mapping are introduced to help organizations anticipate obstacles and proactively design responses. The content also highlights how successful organizations build resilience by embedding contingency planning, feedback loops, and scenario thinking into their strategy process.

A key theme is the importance of strategic self-awareness—understanding where the organization is strong, where it is vulnerable, and how those realities affect the likelihood of strategic success. By taking a proactive stance, organizations are better equipped to reinforce enablers and neutralize disruptors before they become barriers.

Ultimately, this part of the course underscores that strategy is not created in a vacuum. It must be supported by the right conditions and continuously monitored for signs of risk. Recognizing and leveraging strategic enablers is essential for turning plans into outcomes and maintaining focus and agility throughout the execution journey.

Chapter 5: The Cost of Bad Strategy

Poorly conceived or poorly executed strategy can carry a steep price—lost market share, squandered resources, reputational damage, and ultimately, organizational decline. This part of the course examines emblematic failures where reactive decision-making and a lack of strategic foresight set the stage for costly outcomes, distilling lessons that underscore the value of disciplined strategic thinking.

Through guided analysis and structured discussion, participants will explore common patterns found in strategic failures—such as misalignment between goals and actions, resistance to change, poor risk anticipation, and breakdowns in communication and execution. The course uses these themes to highlight the importance of having a strong strategic foundation, supported by disciplined planning and leadership alignment.

Participants will be presented with real-world case material that has been selected not simply to illustrate failure, but to extract meaningful lessons about what could have been done differently. The objective is to encourage critical thinking and to promote reflection on how similar pitfalls might be avoided in other organizational contexts.

Interactive components in this part of the course will support active engagement, including facilitated group discussions, guided debriefs, and targeted reflection exercises. These activities are designed to help participants recognize early warning signs of strategic breakdowns and consider how alternative approaches could have resulted in more positive outcomes.

By the end of this section, participants will have a clearer understanding of how the absence of strategic clarity or execution discipline can lead to costly missteps. The content serves to reinforce the value of applying the frameworks and tools introduced earlier in the course and prepares participants to approach future decisions with a more critical, strategic lens.

Chapter 6: Case Study – Strategy in Action

This part of the executive summary previews a practical case analysis that illustrates how strategic alignment across all management levels can transform a mid-sized manufacturing enterprise. The forthcoming manual will trace a company’s journey from stagnant performance to renewed competitiveness, using the narrative to demonstrate how concepts introduced earlier—vision, alignment, execution, and strategic enablers—translate into day-to-day leadership behaviour and measurable results.

The analysis begins by outlining the firm’s initial conditions: fragmented priorities, siloed decision-making, and eroding market share. Against this backdrop, senior leadership articulates a unifying strategic vision centred on product innovation and operational excellence. Attention then shifts to the cascading process that converts this vision into tiered objectives. Functional leaders translate enterprise goals into department-level targets, while front-line supervisors link individual KPIs to broader outcomes. Throughout, the manual highlights governance mechanisms—balanced scorecards, cross-functional councils, and structured feedback loops—that sustain alignment and foster accountability.

Key success factors receive focused treatment. Leadership commitment emerges as the catalyst that sets clear expectations and allocates resources to strategic priorities. Transparent communication ensures that employees understand how their roles contribute to high-level objectives, reinforcing purpose and reducing resistance to change. Data-driven decision routines, such as weekly operating reviews and quarterly strategy sprints, create short feedback cycles that surface issues early and enable agile course corrections. Continuous-improvement disciplines—including lean methodologies and root-cause analysis—help embed strategic thinking into daily operations, turning incremental gains into sustainable advantage.

The forthcoming case study also examines cultural shifts. By linking rewards to strategic milestones and celebrating quick wins, the company cultivates a performance-oriented mindset that values collaboration over departmental turf. Managers sharpen strategic acumen through targeted training, while cross-training initiatives break down functional barriers and promote knowledge sharing. These behavioural changes prove instrumental in sustaining momentum once the initial transformation phase concludes.

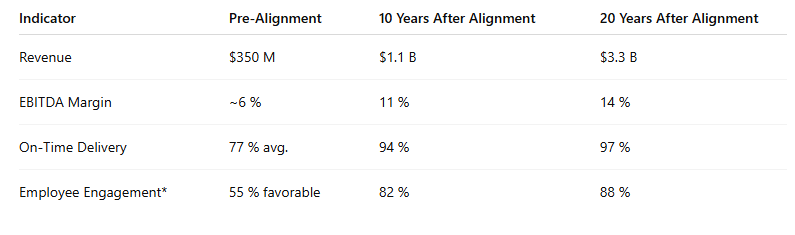

Outcomes are evaluated through both quantitative and qualitative lenses. Metrics such as market share growth, margin expansion, order-to-delivery cycle time, and employee engagement scores demonstrate tangible improvements. Just as important are intangible gains: heightened customer trust, stronger supplier partnerships, and a culture that treats strategy as a living process rather than a static document.

By weaving these elements together, the manual will show how disciplined alignment can reposition a mid-sized manufacturer in a competitive landscape. The case provides a concrete reference point for subsequent course materials, reinforcing the central message that cohesive strategy—backed by consistent leadership behaviours and robust execution systems—can yield outsized impact even in resource-constrained settings.

Chapter 7: Strategic Leadership in Practice

Strategic leadership bridges the gap between aspirational vision and day-to-day execution. This manual examines how effective leaders craft a coherent narrative, convert that narrative into actionable priorities, and mobilise people to pursue those priorities with clarity and commitment. At the centre is the leader’s ability to balance long-range foresight with operational discipline—seeing the organisation as an interconnected system while managing immediate constraints.

The content first traces the pathway from vision to strategy. It explores the decision logic leaders apply when translating a broad ambition into direction-setting choices about markets, capabilities, and resource allocation. Emphasis is placed on clarifying “where to play” and “how to win”—decisions that guide investment, talent deployment, and partnership selection. From there, the manual investigates the mechanics of turning strategy into action: setting cascading objectives, defining lead and lag indicators, and instituting governance routines that keep strategic themes visible amid daily pressures.

Several leadership traits emerge as differentiators of high impact. Systems thinking enables leaders to anticipate second-order effects and avoid silo-optimised decisions. Courageous communication—the willingness to state unpopular truths and challenge entrenched assumptions—creates the psychological safety needed for candid debate and innovation. Adaptive learning equips leaders to pivot strategy when feedback or external shifts render initial assumptions obsolete. Empathy and influence allow leaders to tailor messages to varied stakeholder concerns, turning potential resistance into constructive engagement.

A dedicated section analyses how leaders secure buy-in for strategic decisions. Techniques include framing choices around shared values and long-term benefits, co-creating milestones with cross-functional teams, and using storytelling to connect strategic intent with personal meaning. Case vignettes highlight moments when stakeholder alignment hinged less on formal authority and more on credibility, transparency, and the demonstration of quick wins.

The manual also delves into the structural levers that reinforce strategic leadership: leadership scorecards linked to strategy, incentive schemes that reward cross-unit collaboration, and developmental pathways that build strategic capability across management tiers. By institutionalising these levers, organisations reduce dependency on a single visionary and cultivate a bench of leaders equipped to think and act strategically.

Finally, the material synthesises behavioural research and real-world examples to show how strategic leaders navigate paradoxes—pursuing efficiency and innovation, stability and change, short-term performance and long-term growth. Through this exploration, the manual illustrates that strategic leadership is less about heroic decision-making and more about orchestrating an environment where vision, alignment, and disciplined execution continuously reinforce one another.

Chapter 8: Core Strategic Tools Overview

Strategic thinking and execution are strengthened by the use of structured tools that help clarify choices, organise action, and evaluate progress. This section introduces a set of core strategic frameworks that will be used throughout the program to support decision-making, planning, alignment, and change management.

The manual begins with an overview of SWOT analysis, a foundational tool that helps organisations identify internal strengths and weaknesses alongside external opportunities and threats. It serves as a starting point for strategic assessments and is frequently used to prioritise initiatives and align teams around shared observations.

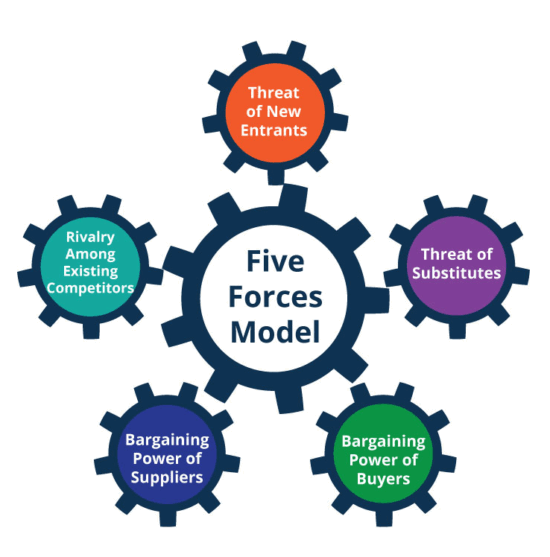

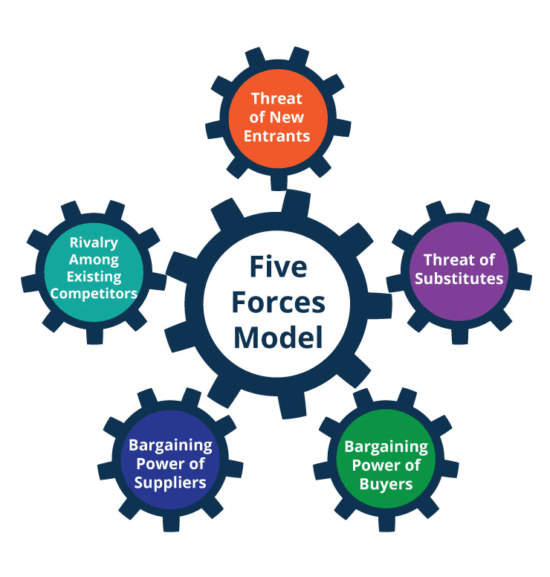

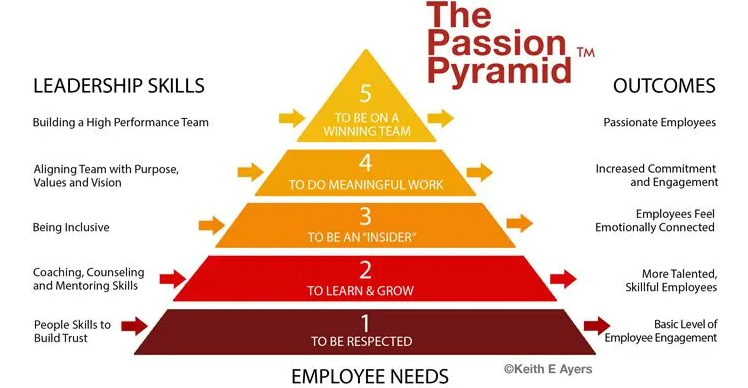

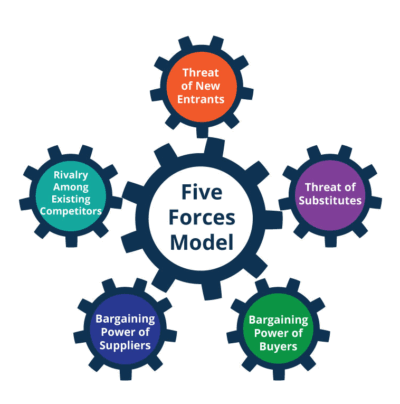

Building on this foundation, the course explores Porter’s Five Forces, which offers a structured approach to analysing industry dynamics. By examining the competitive intensity of a market—including supplier power, buyer influence, threat of new entrants, substitutes, and industry rivalry—leaders can better understand their strategic position and identify levers for differentiation or defence.

Scenario Planning is introduced as a method for navigating uncertainty. Rather than relying on a single forecast, this tool helps teams consider multiple plausible futures, encouraging flexibility and preparedness. Case examples illustrate how scenario planning can guide risk management, innovation, and investment choices, especially in volatile sectors.

The manual also covers the Balanced Scorecard, a framework for translating strategy into measurable performance across four key dimensions: financial outcomes, customer experience, internal processes, and learning and growth. This approach ensures that strategic priorities are tracked holistically, not just through short-term financial metrics.

For execution and role clarity, the RACI Matrix (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) is presented as a practical tool for assigning roles across projects and processes. This framework helps eliminate confusion, streamline communication, and ensure accountability throughout the implementation of strategic initiatives.

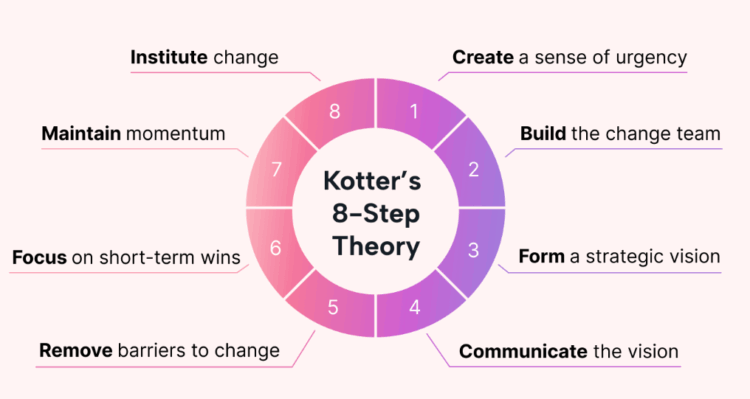

Finally, the section introduces Kotter’s 8-Step Process for Leading Change, a structured approach to driving transformation within organisations. The steps—ranging from creating a sense of urgency to anchoring change in culture—highlight the importance of communication, empowerment, and early wins when embedding new strategic directions.

Simple case applications are used throughout the manual to demonstrate how these tools are applied in practice. The goal is not just to teach the mechanics of each framework, but to show how they complement one another and support an integrated approach to strategy formulation and execution.

Together, these tools form the analytical and operational foundation for the course, equipping participants with versatile methods to address a wide range of strategic challenges in real-world contexts.

Chapter 9: Aligning Strategy with Vision and Values

A well-crafted strategy is most effective when it is rooted in a clearly defined vision and guided by a strong set of core values. This section explores how these foundational elements shape strategic direction, guide decision-making, and sustain alignment across all levels of an organization.

The manual begins by examining the role of vision—a future-oriented statement that articulates what the organization aspires to become or achieve. A compelling vision provides more than inspiration; it establishes a strategic reference point for setting goals, prioritizing initiatives, and evaluating progress. When consistently communicated, a clear vision helps unify efforts and focus attention on long-term outcomes.

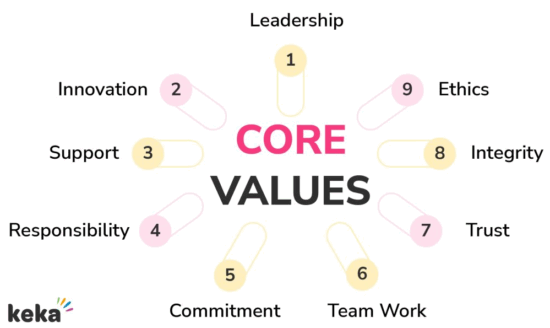

Complementing vision are the organization’s core values, which express the beliefs and principles that shape culture and behaviour. These values influence how strategy is developed and executed, helping to ensure that decisions reflect more than just commercial objectives. Values provide boundaries for acceptable action and serve as a touchstone for ethical leadership, stakeholder engagement, and corporate identity.

This part of the course illustrates how alignment between vision, values, and strategy creates internal cohesion. When strategy reflects the organization’s deeper purpose and principles, it becomes easier to gain buy-in from employees, partners, and other stakeholders. People understand not just what the organization is trying to achieve, but why—increasing trust, motivation, and long-term commitment.

The content also explores risks associated with misalignment. When strategy drifts from vision or contradicts stated values, confusion, disengagement, and reputational damage can result. This section highlights practical ways to ensure alignment, including leadership messaging, cultural reinforcement, and the integration of values into performance measures and decision criteria.

Case-based examples show how organizations embed values into strategic planning processes, from shaping product and service choices to guiding partnerships and talent strategies. The manual also introduces assessment tools that help identify disconnects between strategy, vision, and values, allowing organizations to make timely corrections.

Overall, this section reinforces that vision and values are not separate from strategy—they are integral to it. When aligned, they act as strategic anchors, providing clarity, consistency, and direction even amid change. By maintaining this alignment, organizations can strengthen their identity, build resilient cultures, and execute strategy with greater integrity and impact.

Chapter 10: Strategy Simulation Exercise – Market Disruption

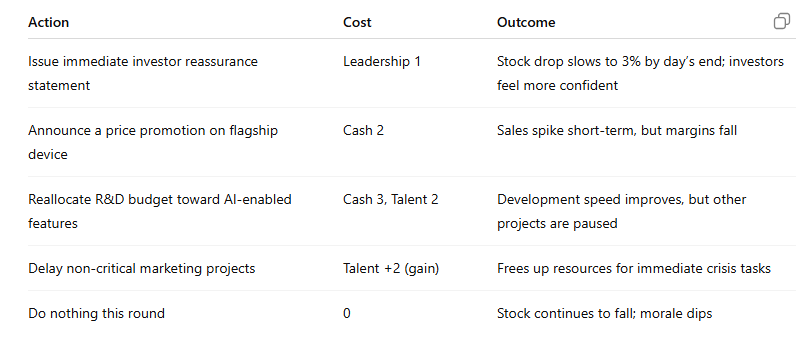

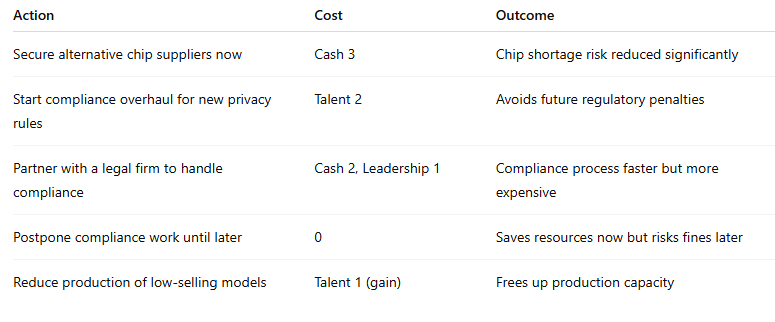

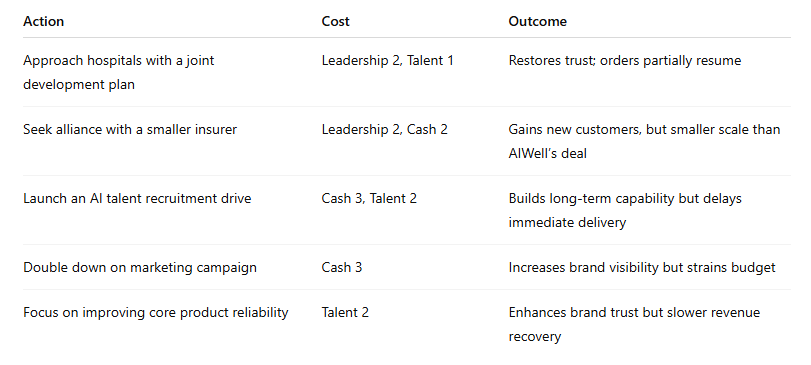

This section introduces an applied simulation designed to bring core strategic concepts to life in a high-pressure, decision-making environment. The exercise immerses participants in a realistic market disruption scenario, where rapid change and external uncertainty challenge the effectiveness of traditional planning. The objective is to test and strengthen the ability to apply strategic thinking under dynamic conditions.

In the simulation, participants are placed in leadership roles within a fictional organization facing sudden shifts in its operating environment. These may include changes in customer behavior, competitor movements, supply chain disruptions, regulatory changes, or technological innovation. Working in teams, participants must assess the situation, identify emerging risks and opportunities, and make a series of strategic decisions in real time.

The exercise is structured around multiple decision points, each requiring careful evaluation of limited information, resource constraints, and time pressures. Teams are expected to define priorities, align choices with a long-term vision, and adjust tactics as new variables emerge. The simulation emphasizes the importance of flexibility, cross-functional collaboration, and the ability to think beyond immediate responses.

Participants will be encouraged to apply tools and frameworks introduced earlier in the course, such as SWOT analysis, scenario planning, and risk assessment techniques. The simulation environment replicates the complexity of real-world strategic challenges and provides a safe space to experiment with approaches, test assumptions, and observe outcomes.

Debrief sessions follow each simulation round, allowing teams to reflect on the impact of their decisions and the underlying thought processes that guided them. These reflections focus on key learning themes: how strategy can prevent reactive behavior, how leadership alignment influences execution, and how effective communication shapes outcomes during uncertainty.

The manual supporting this exercise outlines the structure of the simulation, the strategic tools available to participants, and guidance for group collaboration. It also includes prompts for post-simulation analysis to reinforce the link between theoretical models and practical application.

By engaging in this immersive experience, participants gain a deeper understanding of how strategy functions not just as a planning activity, but as a day-to-day leadership discipline. The exercise highlights the role of strategic thinking in navigating disruption and provides an opportunity to internalize course principles through hands-on experience.

Chapter 11: Getting It Done

A well-formulated strategy is only as effective as its execution. This section focuses on the critical transition from strategic planning to operational delivery, emphasizing the need for disciplined implementation, structured monitoring, and continuous adaptation. It highlights how execution serves as the link between strategic intent and measurable outcomes.

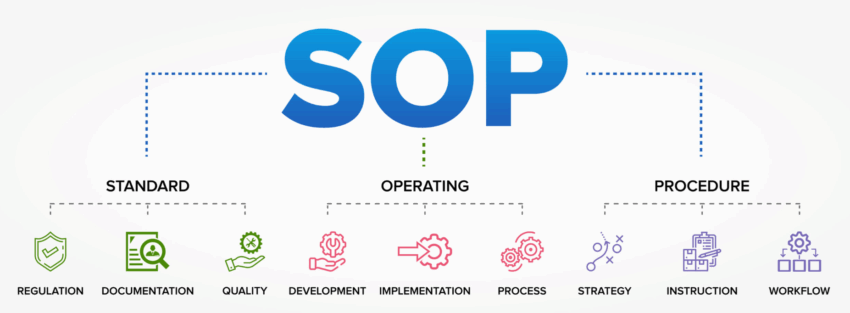

The content begins by outlining the characteristics of a sound execution plan. Key elements include clearly defined objectives, realistic timelines, resource allocation, and role clarity. Strategic initiatives must be broken down into actionable components, supported by operational plans that specify tasks, ownership, interdependencies, and success criteria. Without this level of detail, even the most promising strategy risks falling short due to ambiguity or misalignment.

A strong execution framework also incorporates feedback mechanisms to track progress and enable timely adjustments. This section introduces tools such as key performance indicators (KPIs), milestone tracking, and structured review cycles. These mechanisms not only measure outcomes but also surface implementation barriers, resource gaps, and shifts in external conditions that may warrant a reassessment of priorities.

The manual examines how execution often falters not because of poor strategy, but due to inconsistent follow-through, fragmented communication, or a lack of accountability. To address these challenges, the material explores governance structures such as project steering committees, progress dashboards, and performance reviews that keep strategy visible and execution on course.

Particular attention is given to the role of leadership in reinforcing execution discipline. Leaders at all levels must model commitment to strategic goals, align incentives with desired behaviours, and create a culture where progress is celebrated and course corrections are embraced. The importance of agility—adjusting execution plans in response to new data or emerging risks—is also highlighted as a core component of modern strategy delivery.

Real-world examples and practical frameworks demonstrate how organizations manage execution effectively while remaining flexible and responsive. The content also explores how cascading strategic goals across departments and roles can align teams and promote ownership, ensuring that daily activities support the broader vision.

Overall, this section underscores that delivering on strategy requires more than good intentions—it demands structure, leadership focus, and a commitment to learning and adaptation. By establishing robust execution practices, organizations can bridge the gap between strategy and results, turning plans into sustained performance.

Chapter 12: Your Personal Strategic Edge

Strategic thinking is not only an organizational competency—it is also a personal differentiator. This final section of the executive summary explores how individuals benefit from adopting a strategic mindset, both professionally and personally. It emphasizes that strategic awareness enhances decision-making, strengthens leadership presence, and contributes to long-term career growth and personal fulfillment.

The content begins by examining what it means to think strategically as an individual. This includes the ability to anticipate future challenges, identify patterns and trends, make decisions aligned with long-term goals, and remain focused amid complexity or distraction. Individuals who consistently apply these principles are often seen as forward-thinking, resourceful, and capable of navigating ambiguity with confidence.

In a business context, strategic thinkers stand out by contributing insights that go beyond immediate tasks. They are more likely to propose scalable solutions, align their work with broader organizational goals, and take initiative in ways that generate lasting value. Over time, this approach fosters greater visibility, trust, and influence—key assets for those seeking leadership roles or expanded responsibilities.

The manual also explores how strategic thinking can enhance personal development. By setting clear priorities, defining long-term objectives, and evaluating decisions through a strategic lens, individuals gain clarity and control over their growth. This can apply to a range of areas—from career planning and skill development to financial goals and life transitions.

To support practical application, this section introduces a framework for developing a personal strategic plan. Participants will be guided through reflective exercises that help them define their core values, clarify their vision, assess their current state, and set specific, measurable goals. Tools such as personal SWOT analysis and goal-mapping techniques are introduced to facilitate structured self-assessment and planning.

The content also emphasizes the importance of self-discipline, adaptability, and feedback in executing personal strategies. Just as in organizational settings, individuals benefit from reviewing progress regularly, adjusting plans as needed, and maintaining alignment between values, actions, and long-term ambitions.

In conclusion, this section reinforces the idea that strategy is not confined to boardrooms or business plans—it is a mindset and method that can shape personal trajectories. By cultivating strategic thinking and applying it to real-life decisions, individuals can gain a distinct edge in their professional journeys and achieve greater clarity and purpose in their personal lives.

Curriculum

Mastering Strategy – Workshop 1 – Strategy Matters

- What Mastering Strategy Is All About

- Thinking Strategically

- Benefits of a Strategic Approach

- Strategic Enablers

- The Cost of Bad Strategy

- Case Study – Strategy in Action

- Strategic Leadership in Practice

- Core Strategic Tools Overview

- Aligning Strategy with Vision and Values

- Strategy Simulation Exercise – Market Disruption

- Getting It Done

- Your Personal Strategic Edge

Distance Learning

Introduction

Welcome to Appleton Greene and thank you for enrolling on the Mastering Strategy corporate training program. You will be learning through our unique facilitation via distance-learning method, which will enable you to practically implement everything that you learn academically. The methods and materials used in your program have been designed and developed to ensure that you derive the maximum benefits and enjoyment possible. We hope that you find the program challenging and fun to do. However, if you have never been a distance-learner before, you may be experiencing some trepidation at the task before you. So we will get you started by giving you some basic information and guidance on how you can make the best use of the modules, how you should manage the materials and what you should be doing as you work through them. This guide is designed to point you in the right direction and help you to become an effective distance-learner. Take a few hours or so to study this guide and your guide to tutorial support for students, while making notes, before you start to study in earnest.

Study environment

You will need to locate a quiet and private place to study, preferably a room where you can easily be isolated from external disturbances or distractions. Make sure the room is well-lit and incorporates a relaxed, pleasant feel. If you can spoil yourself within your study environment, you will have much more of a chance to ensure that you are always in the right frame of mind when you do devote time to study. For example, a nice fire, the ability to play soft soothing background music, soft but effective lighting, perhaps a nice view if possible and a good size desk with a comfortable chair. Make sure that your family know when you are studying and understand your study rules. Your study environment is very important. The ideal situation, if at all possible, is to have a separate study, which can be devoted to you. If this is not possible then you will need to pay a lot more attention to developing and managing your study schedule, because it will affect other people as well as yourself. The better your study environment, the more productive you will be.

Study tools & rules

Try and make sure that your study tools are sufficient and in good working order. You will need to have access to a computer, scanner and printer, with access to the internet. You will need a very comfortable chair, which supports your lower back, and you will need a good filing system. It can be very frustrating if you are spending valuable study time trying to fix study tools that are unreliable, or unsuitable for the task. Make sure that your study tools are up to date. You will also need to consider some study rules. Some of these rules will apply to you and will be intended to help you to be more disciplined about when and how you study. This distance-learning guide will help you and after you have read it you can put some thought into what your study rules should be. You will also need to negotiate some study rules for your family, friends or anyone who lives with you. They too will need to be disciplined in order to ensure that they can support you while you study. It is important to ensure that your family and friends are an integral part of your study team. Having their support and encouragement can prove to be a crucial contribution to your successful completion of the program. Involve them in as much as you can.

Successful distance-learning

Distance-learners are freed from the necessity of attending regular classes or workshops, since they can study in their own way, at their own pace and for their own purposes. But unlike traditional internal training courses, it is the student’s responsibility, with a distance-learning program, to ensure that they manage their own study contribution. This requires strong self-discipline and self-motivation skills and there must be a clear will to succeed. Those students who are used to managing themselves, are good at managing others and who enjoy working in isolation, are more likely to be good distance-learners. It is also important to be aware of the main reasons why you are studying and of the main objectives that you are hoping to achieve as a result. You will need to remind yourself of these objectives at times when you need to motivate yourself. Never lose sight of your long-term goals and your short-term objectives. There is nobody available here to pamper you, or to look after you, or to spoon-feed you with information, so you will need to find ways to encourage and appreciate yourself while you are studying. Make sure that you chart your study progress, so that you can be sure of your achievements and re-evaluate your goals and objectives regularly.

Self-assessment

Appleton Greene training programs are in all cases post-graduate programs. Consequently, you should already have obtained a business-related degree and be an experienced learner. You should therefore already be aware of your study strengths and weaknesses. For example, which time of the day are you at your most productive? Are you a lark or an owl? What study methods do you respond to the most? Are you a consistent learner? How do you discipline yourself? How do you ensure that you enjoy yourself while studying? It is important to understand yourself as a learner and so some self-assessment early on will be necessary if you are to apply yourself correctly. Perform a SWOT analysis on yourself as a student. List your internal strengths and weaknesses as a student and your external opportunities and threats. This will help you later on when you are creating a study plan. You can then incorporate features within your study plan that can ensure that you are playing to your strengths, while compensating for your weaknesses. You can also ensure that you make the most of your opportunities, while avoiding the potential threats to your success.

Accepting responsibility as a student

Training programs invariably require a significant investment, both in terms of what they cost and in the time that you need to contribute to study and the responsibility for successful completion of training programs rests entirely with the student. This is never more apparent than when a student is learning via distance-learning. Accepting responsibility as a student is an important step towards ensuring that you can successfully complete your training program. It is easy to instantly blame other people or factors when things go wrong. But the fact of the matter is that if a failure is your failure, then you have the power to do something about it, it is entirely in your own hands. If it is always someone else’s failure, then you are powerless to do anything about it. All students study in entirely different ways, this is because we are all individuals and what is right for one student, is not necessarily right for another. In order to succeed, you will have to accept personal responsibility for finding a way to plan, implement and manage a personal study plan that works for you. If you do not succeed, you only have yourself to blame.

Planning

By far the most critical contribution to stress, is the feeling of not being in control. In the absence of planning we tend to be reactive and can stumble from pillar to post in the hope that things will turn out fine in the end. Invariably they don’t! In order to be in control, we need to have firm ideas about how and when we want to do things. We also need to consider as many possible eventualities as we can, so that we are prepared for them when they happen. Prescriptive Change, is far easier to manage and control, than Emergent Change. The same is true with distance-learning. It is much easier and much more enjoyable, if you feel that you are in control and that things are going to plan. Even when things do go wrong, you are prepared for them and can act accordingly without any unnecessary stress. It is important therefore that you do take time to plan your studies properly.

Management

Once you have developed a clear study plan, it is of equal importance to ensure that you manage the implementation of it. Most of us usually enjoy planning, but it is usually during implementation when things go wrong. Targets are not met and we do not understand why. Sometimes we do not even know if targets are being met. It is not enough for us to conclude that the study plan just failed. If it is failing, you will need to understand what you can do about it. Similarly if your study plan is succeeding, it is still important to understand why, so that you can improve upon your success. You therefore need to have guidelines for self-assessment so that you can be consistent with performance improvement throughout the program. If you manage things correctly, then your performance should constantly improve throughout the program.

Study objectives & tasks

The first place to start is developing your program objectives. These should feature your reasons for undertaking the training program in order of priority. Keep them succinct and to the point in order to avoid confusion. Do not just write the first things that come into your head because they are likely to be too similar to each other. Make a list of possible departmental headings, such as: Customer Service; E-business; Finance; Globalization; Human Resources; Technology; Legal; Management; Marketing and Production. Then brainstorm for ideas by listing as many things that you want to achieve under each heading and later re-arrange these things in order of priority. Finally, select the top item from each department heading and choose these as your program objectives. Try and restrict yourself to five because it will enable you to focus clearly. It is likely that the other things that you listed will be achieved if each of the top objectives are achieved. If this does not prove to be the case, then simply work through the process again.

Study forecast

As a guide, the Appleton Greene Mastering Strategy corporate training program should take 12-18 months to complete, depending upon your availability and current commitments. The reason why there is such a variance in time estimates is because every student is an individual, with differing productivity levels and different commitments. These differentiations are then exaggerated by the fact that this is a distance-learning program, which incorporates the practical integration of academic theory as an as a part of the training program. Consequently all of the project studies are real, which means that important decisions and compromises need to be made. You will want to get things right and will need to be patient with your expectations in order to ensure that they are. We would always recommend that you are prudent with your own task and time forecasts, but you still need to develop them and have a clear indication of what are realistic expectations in your case. With reference to your time planning: consider the time that you can realistically dedicate towards study with the program every week; calculate how long it should take you to complete the program, using the guidelines featured here; then break the program down into logical modules and allocate a suitable proportion of time to each of them, these will be your milestones; you can create a time plan by using a spreadsheet on your computer, or a personal organizer such as MS Outlook, you could also use a financial forecasting software; break your time forecasts down into manageable chunks of time, the more specific you can be, the more productive and accurate your time management will be; finally, use formulas where possible to do your time calculations for you, because this will help later on when your forecasts need to change in line with actual performance. With reference to your task planning: refer to your list of tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve your program objectives; with reference to your time plan, calculate when each task should be implemented; remember that you are not estimating when your objectives will be achieved, but when you will need to focus upon implementing the corresponding tasks; you also need to ensure that each task is implemented in conjunction with the associated training modules which are relevant; then break each single task down into a list of specific to do’s, say approximately ten to do’s for each task and enter these into your study plan; once again you could use MS Outlook to incorporate both your time and task planning and this could constitute your study plan; you could also use a project management software like MS Project. You should now have a clear and realistic forecast detailing when you can expect to be able to do something about undertaking the tasks to achieve your program objectives.

Performance management

It is one thing to develop your study forecast, it is quite another to monitor your progress. Ultimately it is less important whether you achieve your original study forecast and more important that you update it so that it constantly remains realistic in line with your performance. As you begin to work through the program, you will begin to have more of an idea about your own personal performance and productivity levels as a distance-learner. Once you have completed your first study module, you should re-evaluate your study forecast for both time and tasks, so that they reflect your actual performance level achieved. In order to achieve this you must first time yourself while training by using an alarm clock. Set the alarm for hourly intervals and make a note of how far you have come within that time. You can then make a note of your actual performance on your study plan and then compare your performance against your forecast. Then consider the reasons that have contributed towards your performance level, whether they are positive or negative and make a considered adjustment to your future forecasts as a result. Given time, you should start achieving your forecasts regularly.

With reference to time management: time yourself while you are studying and make a note of the actual time taken in your study plan; consider your successes with time-efficiency and the reasons for the success in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; consider your failures with time-efficiency and the reasons for the failures in each case and take this into consideration when reviewing future time planning; re-evaluate your study forecast in relation to time planning for the remainder of your training program to ensure that you continue to be realistic about your time expectations. You need to be consistent with your time management, otherwise you will never complete your studies. This will either be because you are not contributing enough time to your studies, or you will become less efficient with the time that you do allocate to your studies. Remember, if you are not in control of your studies, they can just become yet another cause of stress for you.